I first became familiar with the work of Dr. John T. Biggers in 2013 in my role as the Center for Creative Connections (C3) Gallery Coordinator at the Dallas Museum of Art. Despite his notoriety and legacy (especially in Texas), Biggers was not a part of my high school or even college art curriculum. However, nearly two years after I began working at the museum, the large-scale painting Starry Crown, from its permanent collection, was selected to be on view in the C3 Gallery. In my role at the institution, I wrote label text and created self-guided activities for visitors of all ages. This gave me an opportunity to dig in and learn about the painting and about John Biggers, the person.

John Thomas Biggers, “Starry Crown,” 1987, acrylic and mixed media on masonite. Dallas Museum of Art, Museum League Purchase Fund.

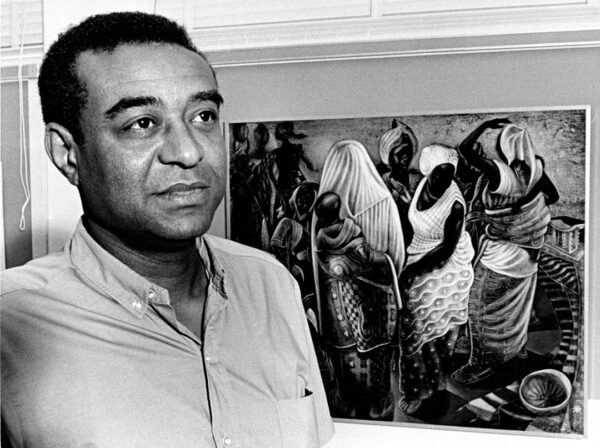

I was immediately enamored by the depth of the symbols and imagery in Biggers’ work and was equally compelled by his story — that of the educators who influenced him and his own legacy as an art educator. Biggers was shaped by significant teachers, including Viktor Lowenfeld, who developed a theory of stages of artistic development that outlined how children’s drawings shift from early childhood to adolescence; Charles White, a prolific artist whose work focused on African American stories and who taught at various institutions throughout his life; and Elizabeth Catlett, a sculptor and print artist who lived in the U.S. and Mexico and is known for her depictions of Black women. In 1949, after his own schooling, Biggers founded the art department at the historically Black college/university Texas Southern University (then the Texas State University for Negroes) in Houston. During his 34-year tenure, he influenced countless artists, including Project Row Houses founders James Bettison, Bert Long, Jr., Rick Lowe, Floyd Newsum, Bert Samples, George Smith, and Jesse Lott.

Earlier this year, when The Grace Museum announced its exhibition Witness: Black Artists in Texas, Then and Now would bring together works by Biggers, some of his students, and younger generations of Black artists from across the state, I was ecstatic. Even now, in 2023, it feels rare to see a show of works by multiple generations of Black artists presented together, let alone Black artists who all have ties to Texas. It’s fair to say that I was surprised to see this show happening in Abilene (a small town in the Texas Panhandle Plains), rather than Houston, where Biggers taught. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston did present the traveling exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, organized by the Tate Modern in London, and supplemented the exhibition with works by Texas artists from the museum’s collection. However, the show was on view for three months in the summer during the COVID-19 pandemic, and didn’t receive as much attention in Texas as it had elsewhere. Prior to that, in early 2018, William Reaves | Sarah Foltz Fine Art (now Foltz Fine Art) presented Protégés: The Legacy of Dr. John Biggers: As Viewed Through the Works of Thirteen Students.

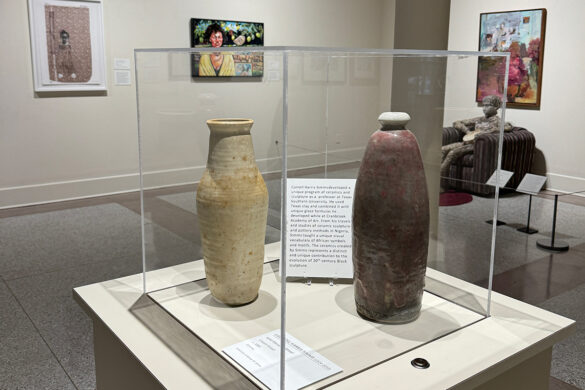

Organized by Chief Curator Judy Tedford Deaton, Witness brings together works by Biggers, his students (Charles Criner, Geraldine “Gerry” Crossland, Karl E. Hall, Harvey Johnson, Earl S. Jones, Bert Long, Jr., Kermit Oliver, Elizabeth Montgomery Shelton, and Roy Vinson Thomas), his colleague Carroll Harris Simms, and other artists influenced by his work (Spencer Evans, Johnny Floyd, Riley Holloway, Letitia Huckaby, Sedrick Huckaby, and Delita Martin (who graduated from TSU with a BFA in 2022)). Deaton told me that the exhibition has been in the works for four years, noting that because some larger institutions are hesitant to loan works to smaller museums like the Grace, she worked diligently to secure loans from private collectors. While the process was surely arduous, the result is a unique exhibition featuring many pieces that are rarely accessible to the public.

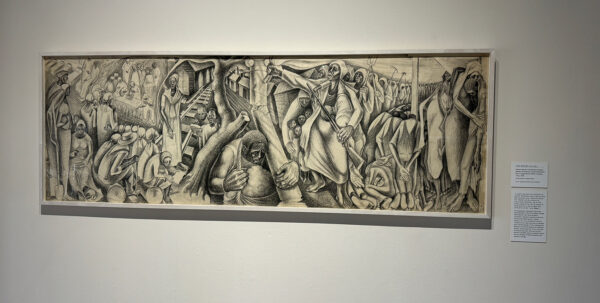

John Biggers, mural study for “Contribution of the Negro Women to American Life and Education, Blue Triangle Branch YWCA, Houston, Texas,” 1952-53, conté crayon on paperboard. The Dr. Gregory Shannon Family Collection, Houston.

Though the exhibition is rooted in Biggers’ work, some of which appears at the onset of the show, it is not presented in chronological order. There are also no themed sections; instead, across four galleries and two floors, Deaton has arranged effective pairings and placed works to spark thoughtful considerations, without overly directing the viewer. Deaton explained that rather than using a to-scale model to arrange the exhibition, she determined placement in the galleries, spending time with the physical works and making intuitive arrangements.

While chronological exhibitions can illustrate growth, change, and evolution over time, sometimes these presentations also oversimplify history. Similarly, a thematic show might constrain the audience’s experience and understanding by presenting specific ideas that viewers then don’t look beyond. However, life and art are much more complicated — there is rarely a singular path or line between two things. Deaton’s decision to forego these traditional modes of curation creates space for the messy web of connections that tie the artists and their practices together.

Near the entry of the exhibition, Spencer Evans’ Make Me Wanna Holler hangs on a wall adjacent to Charles Criner’s Mrs. Willie John. (Disclosure: Evans exhibited work at Kinfolk House, an art space founded by Sedrick and Letitia Huckaby in Fort Worth, while I was the space’s director. Evans also studied under Sedrick at the University of Texas at Arlington.) Each work depicts a singular, striking figure, though the subjects’ demeanors are diametrically opposed. Though much of Criner’s oeuvre features Black figures in action, including fishing scenes, people at work, and figures dancing, his included portrait, Mrs. Willie John, presents a stoic image of a woman full of both power and grace. Despite the bright colors of her attire, she holds a calm, steady pose.

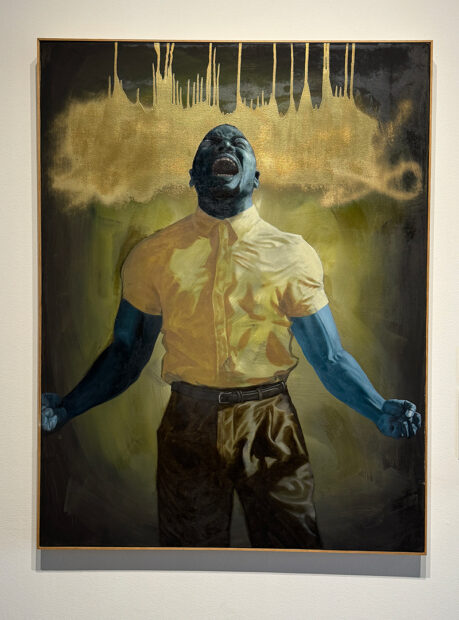

Spencer Evans, “Make Me Wanna Holler,” 2015, oil on canvas. Collection of Stephen and Candance Bossay.

In contrast, Evans’ Make Me Wanna Holler features an almost primal scream into the void. The figure’s face is dramatic and agonizing, and we can see the veins in his arms bulge as he clenches his fists and stiffens his body. This type of theatrical scene is similar to other works by Evans, who, according to his website, aims to “contextualize relationships between internal conflict and external circumstance.” The title of the painting references Marvin Gaye’s Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler), a song lamenting the social, economic, and political injustices faced by Black people in the U.S. Similar to Criner’s portrait, Evans uses unreal colors with a greenish cloud hovering behind his blue-skinned figure.

While both works are strong and significant in their own right, pairing the portraits adds a new layer to each. In the galleries I stood between the two works, looking back and forth at them and considered how Evans’ portrait might reflect an inner turmoil that Mrs. Willie John holds quietly inside.

Left: Riley Holloway, “My Mother,” 2016, oil on panel. Private collection. Right: Karl E. Hall, “Unc Roosevelt,” 1978-79, color monotype. Courtesy of the artist and Foltz Fine Art.

Further into the first floor of the show, I was drawn to Riley Holloway’s My Mother, a large horizontal painting of a Black woman in profile. The figure’s white shirt melts into the background, which at once feels reminiscent of a kitchen with black cabinets and an abstract composition of neutral colors. Holloway’s loose brushwork, and at times his thick paint application, harkens back to a style associated with Sedrick Huckaby, one of Holloway’s instructors at UTA, who is also featured in Witness. Holloway often depicts his mother in his work, and it’s clear throughout the exhibition that the idea of family is a unifying theme across many of the artists.

Catty-corner to Holloway’s portrait is a color monotype by Karl E. Hall titled Unc Roosevelt. Whether or not the person depicted in the work is kin to Hall, the piece and its title still speak to the importance of familial and familiar relationships. Though the work is a print, as a monotype it maintains a painterly quality that speaks to Holloway’s portrait. And, similarly to My Mother, the background has an element of abstraction.

Left: Johnny Floyd, “May Gravity Find No Purchase,” 2022, acrylic and oil on canvas. Courtesy of the artist and Conduit Gallery. Right: Letitia Huckaby, “By the Same Cry and Song,” 2020, pigment print on cotton fabric with embroidery hoop. Collection of the Tyler Museum of Art.

On the second floor of the museum I quickly focused on Johnny Floyd’s May Gravity Find No Purchase, because its composition, colors, and texture are unique within the scope of the exhibition. The painting is one of most abstract works in the show and uses an array of bright pastels. Additionally, some areas of the piece are cracked, due to the application of acrylic paint over oil. The work almost felt out of place, until I stepped back and took in its neighbor, Letitia Huckaby’s By the Same Cry and Song.

Both pieces feature silhouetted figures, curved lines, and vivid colors. While Floyd’s painting uses an arch shape within the composition, Huckaby’s print on fabric is presented inside of an oval-shaped embroidery hoop. The pairing of the archway and silhouettes set against radiant backgrounds is reminiscent of stained-glass windows and gives each of the figures a sacredness.

Left: Delita Martin, “Walk with Me,” 2016, gelatin printing, conte, acrylic, hand stitching, fabric. Collection of Russell and Michelle Tether. Right: Harvey Johnson, “Sanctuary,” 1980, conté crayon on paper. Courtesy of the artist.

Also on the second floor is a pairing of works by Delita Martin and Harvey Johnson. Martin’s Walk with Me features a female figure walking side by side with her blue transparent shadow. The title coupled with the shadow, perhaps a placeholder or open space for the viewer to envision themselves, act as an invitation for the audience to consider the ways they show up and support others, particularly Black women. The woman in the work stands tall and peers directly at the viewer with confidence, exuding a desire to work together as equals rather than a need to rely on another. Similar to other works by Martin, this piece is filled with patterns, both through printing processes and sewn fabric.

Visually, Johnson’s Sanctuary is also enveloped in patterning; each of the three figures depicted wear fabrics with patterns similar to many of those that appear in Biggers’ work, referencing both the African American tradition of quilting and West African textile motifs the artist observed during his travels to Ghana, Benin, Nigeria and Togo. Placing Johnson’s and Martin’s pieces together makes a visual connection across the 36 years separating the works, reminding the audience of the connectivity across generations that culture and traditions afford. Beyond the use of patterns, the pieces both illustrate strength and unity. While Martin’s figure stands alone and invites us in, Johnson’s figure cradles and protects two children in need of comfort.

With nearly 70 works in the exhibition, these pairings just scratch the surface of the depth of Witness. Though not laid out thematically, through the exhibition the audience can make connections across time between themes in Biggers’ work and those of artists working today, including the importance of women in Black life and history, strength and unity through family and community, the significance of place and geography, and visual elements and references such as patterned textiles, animals, and elongated figures.

Witness: Black Artists in Texas, Then and Now is on view at The Grace Museum in Abilene through February 3, 2024.

2 comments

What an insightful article. Even being a lender to the exhibit, I learned a lot from your analysis. Thank you.

Wonderfully observed!!