Trauma. It’s a word that has become a part of our mainstream lexicon. Once associated with veterans of war, we now understand that trauma can be experienced in the trenches of everyday life. Whether through big or small events, like a series of stressful moments or the cumulative effects of racism, trauma is pervasive. It can leave scars not only on ourselves but on our families of today and tomorrow, passed down through generations. The effects are emotional, psychological, and even physiological. Specialists like Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, one of the best-known psychiatrists who studies trauma, has dedicated his career to asking the question: how can people gain control over the residues of past trauma and return to being masters of their own ship?

Kinfolk House in Fort Worth has one answer: through the power of art. Following themes of self and community care in this year’s projects, the collaborative art space’s latest installation, Echoes of Our Ancestors, explores stories of internal conflict, trauma, loss and communal healing through the work of three artists: Spencer Evans, Sandra Scott-Revelle, and Felicia Jordan.

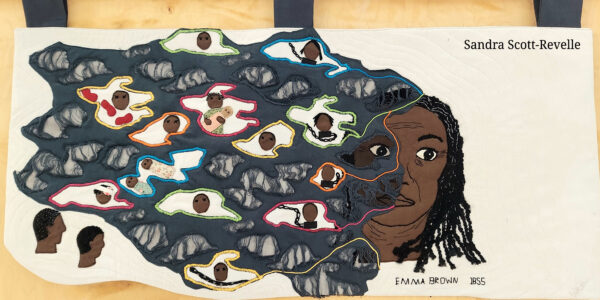

A textile artist with ties to Missouri and East Texas, Sandra Scott-Revelle connects viewers to lessons in Black history and generational trauma through her visualizations of the many emotional narratives of enslaved Black people in the U.S. Diving deep into the Depression-era transcripts of recorded stories of formerly enslaved people, Scott-Revelle responds to a particular scene that reverberates in her mind as she reads each interview. She then reimagines those experiences through fabric and thread.

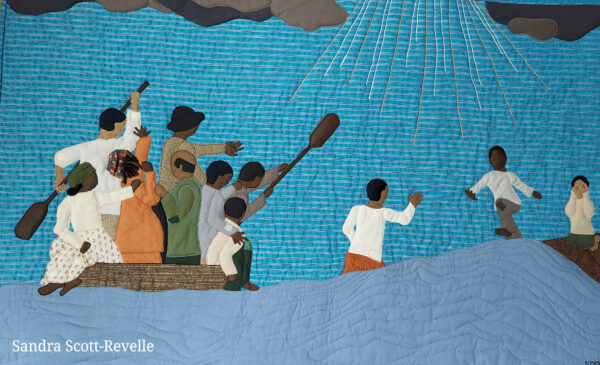

One such powerful history retold through textiles is The Exchange (2022), where a group of runaways in Kentucky escape to freedom across the Ohio River, barely fitting into their small boat. But stranded back on the riverbank we see two figures remaining. One of the passengers jumps from the boat, offering his place. The artist highlights this gallant sacrifice through the embroidered rays of sunlight breaking through the clouds above. “Greater love has no man, than he lay down his life for a friend.”

Scott-Revelle’s raw-edged appliques are rich with texture and intricate in detail. Her use of brightly patterned fabrics contrasts the dark, emotional dramas carefully hand-stitched together. Yet, while the stories themselves are heart-breaking, the artist focuses on the strength and heroism of these real-life characters, like Mary Epps, whose fifteen children either died or were sold into slavery. The effects of her trauma were consuming: she experienced convulsions and was mute for over a month. Yet, she persisted. Epps ran away to freedom in Pennsylvania, where she not only reunited with her husband and one remaining son, but also a new identity, taking on the name Emma Brown. Rather than wallow in the bleak, Scott-Revelle’s pieces defy victimhood and uplift perseverance.

Currently a professor at the Rhode Island School of Design, Houston-born artist Spencer Evans focuses on the Black figure in his work. Evans describes his art as an attempt to visually depict the relationship between the inner self and the outer self within the context of one’s circumstances. What is your true self? And how does that differ from the identity you’ve crafted for largely white-dominated worlds? How do you express yourself freely?

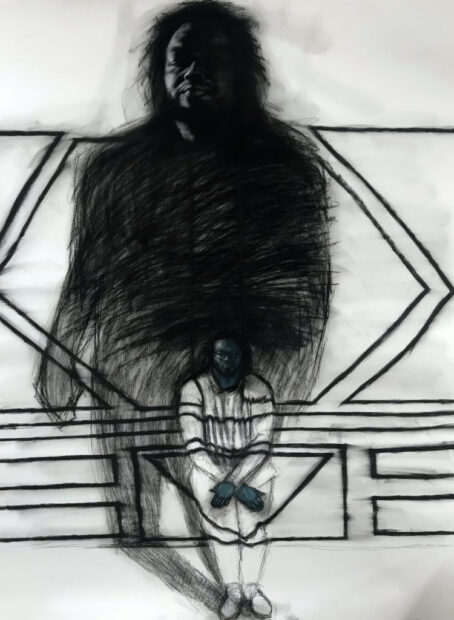

In the case of his portrait of Fort Worth-based artist Charles Gray in You See it (Shadow Clone Big Plates) (2019), Evans imagines Gray’s larger-than-life strength, almost as if it’s his super power. Or in the case of Light Bender (Erro), Evans focuses on the power of bringing light to darkness, or the power to bring truth to light. Our world could use a lot more light benders.

Spencer Evans, “You See It (Shadow Clone Big Plates),” 2019, charcoal and pastel on Arches paper, 60 x 48 inches.

The artist likes to bend or even break the rules of drawing. For him, a drawing is that which shows the relationship between the mark and the surface. Therefore, Evans doesn’t confine himself to traditional pairings of media, as seen in the mixture of acrylic paint with pastel in Light Bender (Erro). For his large-scale works, he will often draw with a dowel rod, which helps to keep him not only loose in gesture but also loose in ideas about perfection. He’s open to opportunities to respond to the moment, remaining sharp and flexible.

Though many of Evans’ artworks on display are predominantly in black and white, the skin of his Black subjects stands out. They’re each a shade of blue. Look through a collection of his paintings and drawings and you’ll find many of what Evans calls the Blue Folk. The artist pulls some inspiration from his love for graphic novels and anime, sometimes escaping into a world of his creation with a comic series he’s in the process of crafting called “Fellowship.” But in looking at his blue-hued figures, I’m also reminded of the many different beliefs in the power of blue, like in the Gullah Geechee culture of the Southeastern U.S., who believed that the indigo-sourced color protects against evil spirits. In a broader context, though blue is often associated with sadness and sorrow, there is a sense of strength and resilience in Evans’ Blue Folk.

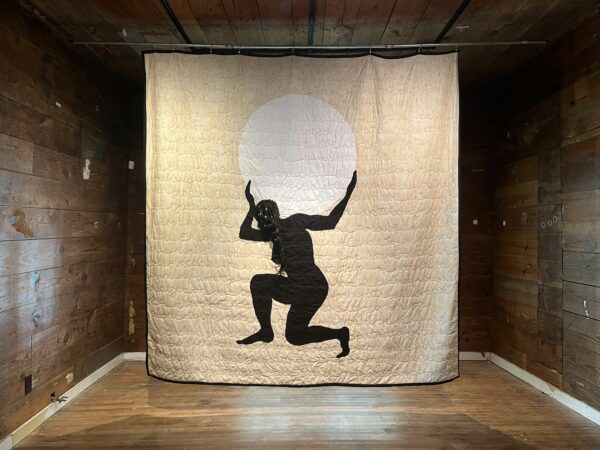

Walking through Echoes of Our Ancestors, for me the ultimate show stopper is Felicia Jordan’s nearly nine-foot-tall quilt, Atlas Shrugged…And Walked Away (2023). A Dallas-based multidisciplinary artist, Jordan’s recent foray into quilt making is big, bold, and dynamic. Illness and navigating the complex industry that is our healthcare system — and the trauma that it inflicts, particularly on people of color — are prominent themes in her work. (Jordan’s father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and she lost her mother to cancer a few years ago.)

In Atlas Shrugged…we see the silhouette of a woman kneeling, and, like the Greek Titan, balancing the weight of the world on her shoulders. Behind the figure is text stitched into the entirety of the quilt, the handwriting of a caretaker transcribing a diary of sorts that documents her husband’s recent doctor visit. Walk around to the backside of the quilt and we see the woman’s silhouette, now in white against a dark background as she stands, removes her weight, and walks away. You feel both the woman’s struggle and her strength. It is an emotionally powerful piece.

Emotions play a part in Jordan’s Cerebral Play series as well. The artist has created interactive pieces in the form of circular puzzles that visitors are invited to play and solve. The puzzles are lined with text that repeats itself, inspired by the conversations the artist has had with her father whose mind has succumbed to the deteriorating effects of dementia. Here, you feel frustration not only from Jordan and her father, but from yourself as you struggle to connect the missing pieces. And yet, you persist.

The works in this latest Kinfolk House project elicit moments of reflection, connecting with past traumas while also reveling in moments of joy and resilience. Encountering these artists’ pieces within the walls of a 100-year-old family home adds a level of intimacy to the experience as you see the work walking through galleries referred to as the Living Room or Big Momma’s Bedroom. The history of the space shortens the emotional distance between the viewer and the artwork. For me, one of the most meaningful functions of art is its capacity for connection, not just with an artwork, but with others and with ourselves. I felt that sense of connection in Echoes of Our Ancestors.

Echoes of Our Ancestors is on view at Kinfolk House in Fort Worth through August 5, 2023.