The images in Paul Hester’s current exhibition of photographs, Prisoners of Masculinity, are organized by architectural elements that frame and obscure the visual field. Hester’s stunning compositions are marked by moments of surreal, spontaneous insight that pierce the environs within which bodies, and the narratives they enact, are posed. The title of the show suggests normative frameworks that Hester’s photographs seek to disrupt. In these formally rigorous images, there are insinuations, or registers of intense emotion that inflect, irradiate, and unsettle the language of architecture, of the monumental, of photography itself.

Hester’s camera explores lavish and utilitarian spaces: glassed-walled high-rise office buildings, barbershops, street scenes at cafes, or storefront rooms with plate glass windows, interiors and exteriors creating frames within frames. Hester, who studied architecture, has a keen compositional eye for the way space is orchestrated, how we comport ourselves within cathedral-like bank lobbies or mingle in crowds on street corners. Hester often locates the human figure in the field of the architecturally monumental.

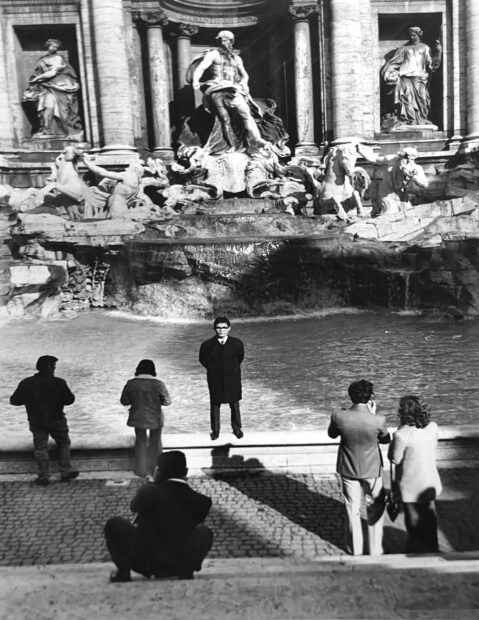

In one photograph, a man poses, hands clasped behind his back, in front of the Trevi Fountain in Rome. This image includes people, presumably tourists, taking photographs of the fountain. The man is not posing for Hester, but for someone else. Hester reveals to us that his is not the only camera present. Hester’s reference here to photography suggests how we use images to describe the world, what we include and what we exclude, just as architecture encloses the spaces we inhabit, and monuments frame our histories. The man’s dark hair, glasses, and dark coat cut a small but sharp figure against the water of the fountain; he seems to levitate there, almost as if posing in front of a green screen. This modern figure defines itself in sharp contrast to the pale, roiling mythical figures of the fountain, which crowd behind him like storm clouds, as if they might at any moment, despite their furious energy set in stone, disappear. In a companion photograph, the dark silhouette of a boy, frail and anonymous, reads like a cipher in front of the incandescent, rushing Waterwall at Williams (formerly Transco) Tower in Houston. The seething force of the monumental rises up and renders us as shadows. But when you look closely, the silhouette of the boy poses defiantly.

Hester’s photographs explore the force and pathos of a world that humans have designed. This includes the body itself as it is “built,” and its power to frame itself and others. “We are seduced by posture,” “We are seduced by gender,” as the texts printed on two of Hester’s photographs remind us. Alongside images of muscular men, some seemingly taken during bodybuilding competitions, Hester shows us women wrapped in tissue paper, their breasts exposed, or women who have been “caged” by markings on the image.

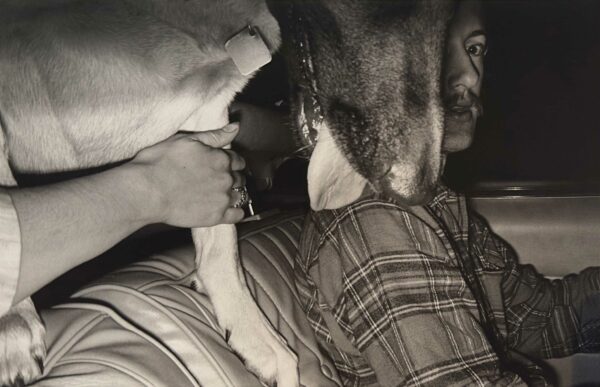

In several photographs, Hester uses the anatomy of animals and humans to create a compositional architecture: The shoulder and truncated head of a dog perch atop the front seat of a car, a young man at the wheel turns his partially obscured face to the camera, a ringed feminine hand holds the leg of the dog. In another image, an alligator wrestler lies on his back, clutching a supine alligator. In one photo, two women, only their torsos visible, manicure the tail of a bull, its testicles prominent below. Their bare arms stand out in striking contrast to the animal’s hide. There is a strange, even grotesque, intimacy in these photographs, the bulk and heft and tactile surfaces of parts of bodies framing one another. Grotesque in Donna Haraway’s sense of the “monstrous” as chimerical, as transforming and transcending the normative.

Hester imagines both a meditative and dramatic relation between people and the material structures that enclose them. At times, figures seem to reside intimately within grand architectural enunciations of space: The Republic Bank in Houston, where two female employees, one white, one Black, work at their desks as a towering wall of interior windows rises behind them like giant tablets of empty space. Through these windows, we see a succession of walls of interior windows; a proliferation of arches and partitions. The women seem quietly focused and active within this bewilderingly and expansively patterned space.

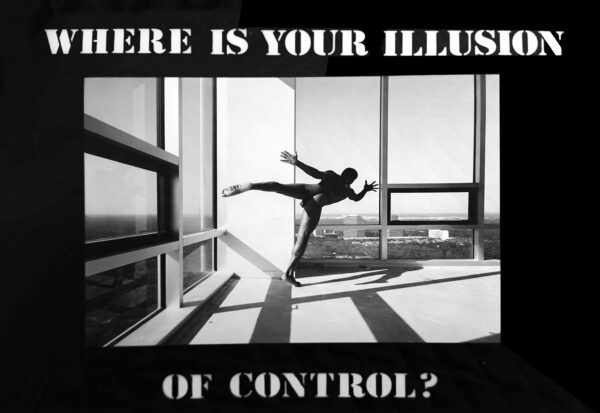

In another image, a Black, male, muscular body tilts, balancing himself on one foot as he reaches toward an immense glass wall scored with the hard lines of giant window frames within the interior of a highrise somewhere in Houston. The enormous boxed frames, against the blinding light of the sky, yield bars of heavy shadows that sprawl across the floor of the room. This photo contains the printed text, “Where Is Your Illusion of Control.”. Is this text interrogating the naked figure reaching toward something out beyond the glass on the distant horizon, or does it suggest the ephemerality of the space itself, the illusion of both permanence and impermanence suggested by the design that attempts to contain the figure?

In Hester’s photograph Quinceañera, Espinazo, Nuevo Leon, Mexico, a group of young girls pose in laced frocks as an old man brings in a beheaded “fatted calf,” presumably to be roasted for the festive occasion. An open door neatly divides the composition into two frames, separating the girls from the old man approaching the doorway. The division heightens the drama. Two of the girls seem to wait expectantly, perhaps hearing someone entering the room but not yet able to see the gruesome offering. The old man’s lost look belies the deadly force of the sacrificial gift he offers to them, death located within our rituals marking the passage of time. The girls are just beginning to break out of their poses; perhaps they sense some dark, unbidden thing arriving.

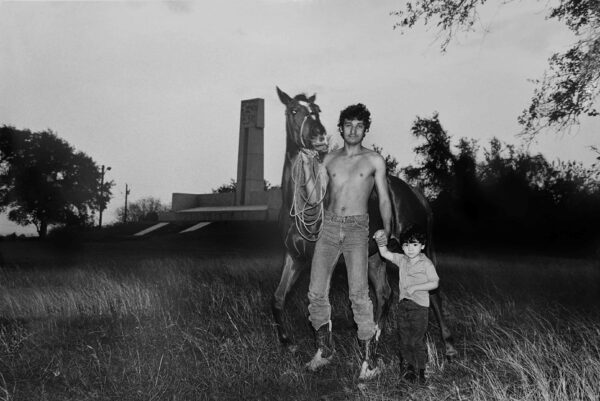

While the name of Hester’s photograph, Fannin’s Men, conjures the ghosts of those executed at Goliad, the image itself captures a moment that redefines the parameters of the monumental. A beautiful young Tejano man, shirtless, wearing jeans and cowboy boots that accentuate his lithe torso, leads a horse while holding the hand of a young Tejano boy, himself dressed sharply in shirt, jeans, and boots; they are the original vaqueros. The Goliad monument, sphinx-like, looks away behind them. Hester composes the photograph perspectively so that the figures and the monument are the same size and on the same plane. The man leads the horse and the boy toward the viewer, illuminated by the camera’s flash, while the darkened monument behind, dumb with its riddle, seems almost unmoored, floating in space. In this photo, Hester subtly captures a landscape where architecturally monumental traces of the violence used to create nations, and frame bodies historically and politically, are left behind. Here, the living body becomes a counter-monument, perhaps a romantic one. Is the only way of demythologizing, of laying to rest, the “martyred,” “heroic,” dominant white body, to counter it with the composed, romanticized brown body? And yet, does the man in the photograph not have the power to inspire and subvert architecturally and photographically defined space? He has his own story, his own relation with the land. In this striking photograph, the brown body, mortified in contested border spaces, glows. The marker echoes the head of the horse so that the man seems to be leading them both as they move out toward a broader historical terrain. The opacity of history now lit up by the young man’s physical presence, his bright breast cleaving the darkness.

2 comments

Wonderful work and review.

This lyrical essay is truly a fantastic introduction to his work.