Introduction

The Texian Revolt — and the Battle of the Alamo in particular — are bitterly contested subjects. Many accounts are based on sheer fantasy and wholesale misrepresentations. My objective is to disentangle the Alamo and its historical context from its enfablement in Texas myth and folklore. After this introduction, I list a number of myths in all-caps, followed by a discussion of scholarly works that refute these claims. (This content is excerpted from the introduction and first chapter of my exhibition catalogue, The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth, San Antonio: Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, 2018.)

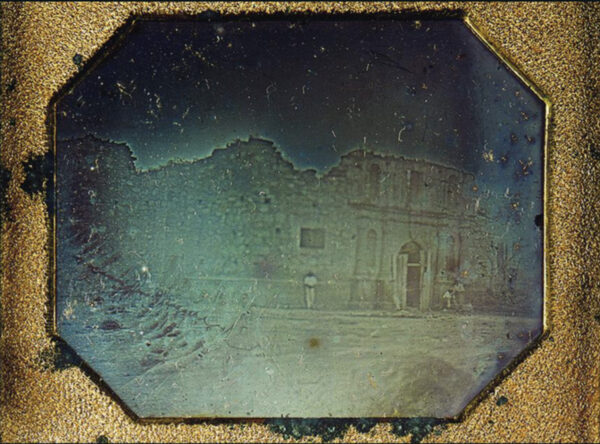

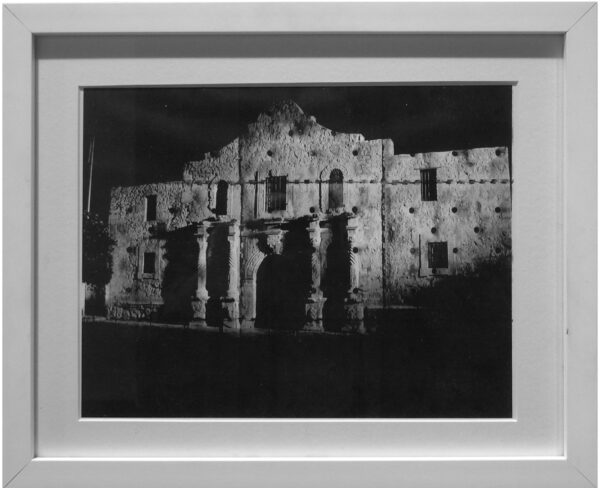

Daguerreotype with the façade of the Alamo church, 1849. Photo: Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin. This is the only known photograph of the Alamo church before the Army Corps of Engineers added a roof and a Taco Bell-like hump to its façade in 1850.

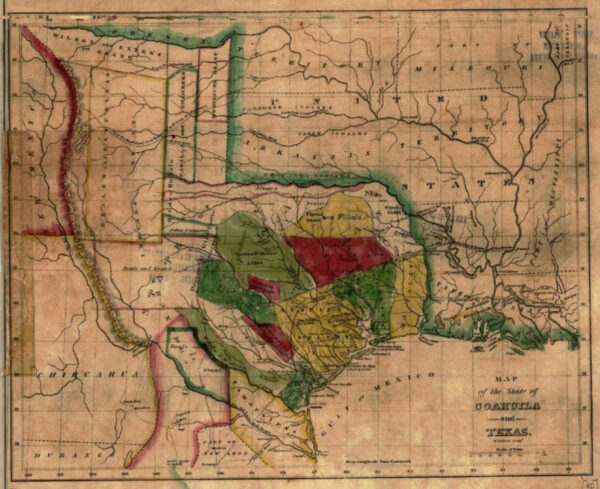

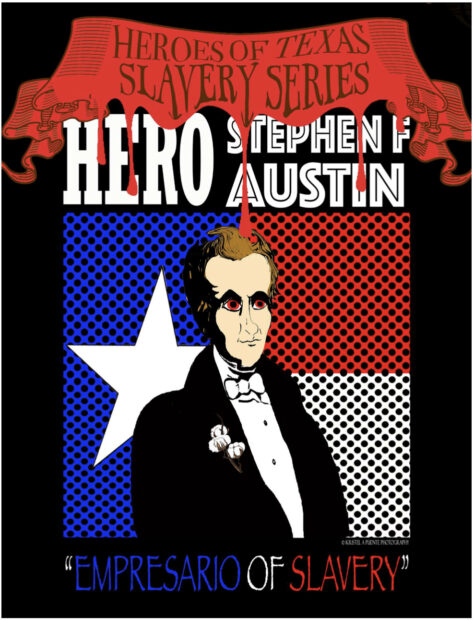

Stephen F. Austin, the most important empresario (land agent), began bringing Anglo-American settlers into the Mexican state of Coahuila and Texas in 1821. Austin replicated the structures of Southern slave states in his settlements, and cotton production grew exponentially. Due to internal political conflicts, Mexico exerted little control over Anglo-American colonies in what is now Texas. The colonists’ commitment to slavery was a source of continuous conflict with Mexico, on both the state and national level. Mexico made a belated effort to end Anglo-American immigration in 1830, but they continued to flood into Texas, doubling their number by 1834 from 10,000 to 21,000 (Torget, 2015: 150-57).

Map of the State of Coahuila and Texas, 1836. Photo: The Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

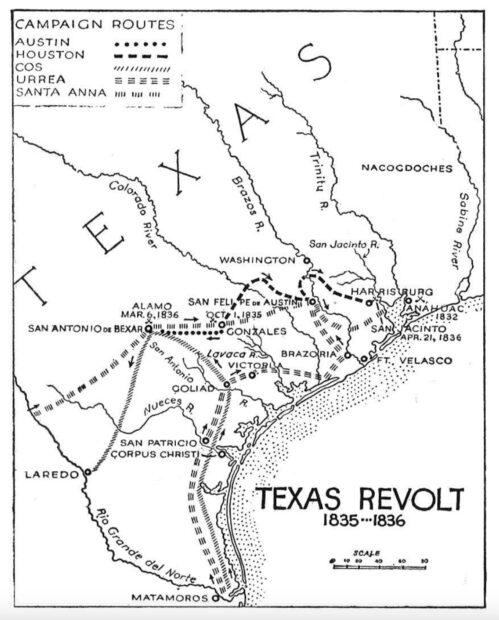

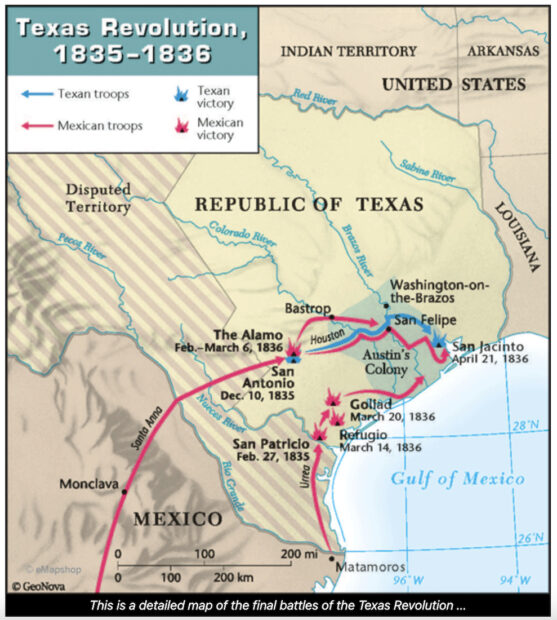

An armed insurrection against Mexico broke out in 1835. San Antonio and the Alamo (the former Mission San Antonio de Valero) were captured by an army composed primarily of rebels, squatters, and mercenaries from the U.S. in December of 1835. On March 2, 1836, a convention (made up largely of relatively recent arrivals from the U.S.) declared independence from Mexico, inaugurating the slavery-based Republic of Texas, which has been called a “dress-rehearsal” for the Confederate States of America (Torget, 2015: 12, 263). Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna began his siege of the Alamo on February 23, and he recaptured it during a short battle on March 6. Santa Anna’s capture at San Jacinto in April of 1836 brought an end to the war.

Campaign Routes of the Texas Revolt (1928), drawn by Joseph L. Cain. Photo: Handbook of Texas Online.

The Anglo-American rebels referred to themselves as Texians (this term helps to differentiate them from the ethnically Mexican inhabitants of Texas, who are called Tejanos). I refer to the 1835-36 war of independence as the Texian Revolt rather than the Texas Revolution, because it does not fulfill the criteria of a revolution (Reichstein, 1989: 191-196; Reichstein, 1989b). The Republic of Texas came to an end on December 29, 1845, when it was annexed (without defined borders) to the United States as Texas, a slave state. Annexation to the U.S. had been the goal of the independence movement because annexation served to secure the land taken from Mexico, to safeguard the institution of slavery, and to facilitate continued Anglo-American immigration. The state of Texas lacked defined borders by design: this deficiency made it easier for the U.S. to provoke the Mexican-American War in 1846. This war of conquest resulted in the seizure of Mexican territory all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

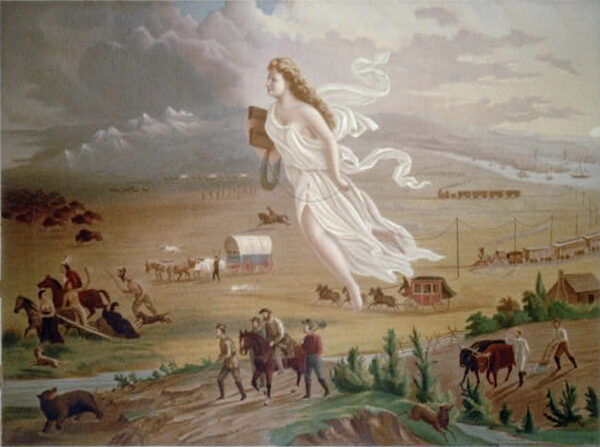

Texas was the crucible for the rise of a racialized Anglo-Saxonism, one that regarded dominance as its special destiny. The term Manifest Destiny was coined in a discussion of the U.S. annexation of Texas in 1845, the very act that precipitated the Mexican-American War (Horsman, 1981: 119-221). Jeff Long (1990: 258) calls March 6, 1836, the date of the Battle of the Alamo, “the inaugural moment of Manifest Destiny.” As one of the most enduring and potent symbols of Anglo-American power and triumph, the Alamo has often functioned as the quintessential anti-Mexican emblem, one that marks Mexicans and their descendants as the villains of Texas history, and one that perpetually seems to cry out for vengeance for a long-lost battle.

John Gast, “American Progress,” 1872, oil on canvas, 11 ½ x 15 ¾ inches, Autry Museum of the American West, Los Angeles. Photo: Library of Congress. Gast’s painting, which features a white goddess with a book in one hand and a telegraph wire in the other, is the quintessential image of Manifest Destiny. Note how buffalo, Native Americans, and a bear are being driven out of the picture frame on the left.

The Texians were quick to characterize their Alamo heroes in both religious and mythic terms. On March 24, 1836, the Telegraph and Texas Register declared: “Honors and rest are with ye: the spark of immortality which animated your forms, shall brighten into a flame, and Texas, the whole world, shall hail ye like demi-gods of old, as founders of new actions, and as patterns of imitation” (Hutton, 1995: 17). Two days later, a resolution by the city of Nacogdoches called them “martyrs to liberty” and equated them with the most revered martyr-warriors in Western history, the 300 Spartans who fought for Greece against a Persian invasion in 380 B.C.: “Thermopylae, is no longer without parallel… Travis and his companions will be named in rivalry with Leonidas and his Spartan band” (Hutton, 1995: 17).

Thermopylaen invocations became “so pervasive” in treatments of the Alamo that one observer said “it almost seems a law that each novel, drama, or poem must contain its own” (Graham, 1998: 240). Lawyer, politician, land speculator, and diarist William Fairfax Gray evidently foresaw this phenomenon. Gray, who was appalled that the Alamo garrison had not been reinforced, had this to say about historical hypocrisy and mythification: “Texas will take honor to herself for the defense of the Alamo and will call it a second Thermopylae, but it will be an everlasting monument of national disgrace” (Tucker, 2010: 329).

Anna J. Pennybacker, “A History of Texas for Schools, also for General Reading and for Teachers Preparing Themselves for Examination.” Photo: Library of Congress.

If, in 1836, the Alamo occupiers were likened to demi-gods, they were further elevated in an 1888 textbook that was used in Texas for forty years: “The Texans stood like gods waiting to let others feel their mighty strength” (Pennybacker, 1888: 76). This textbook, which refers to Mexican soldiers as “fiends” and “servants of the ‘Prince of Butchers,’” calls each Texian soldier “a bleeding sacrifice upon his country’s altar” (Pennybacker, 1888: 78, 88). Finally, after denouncing the cremation of the Texian dead, Anna J. Pennybacker celebrates its effects: “From that sacred fire sprang the flames that lighted all Texas” (1888: 78-79). Such hagiographic martyrologies served a heady mix of racism, myth, grandiosity, and religion, a heritage that endowed Texas history with its special character.

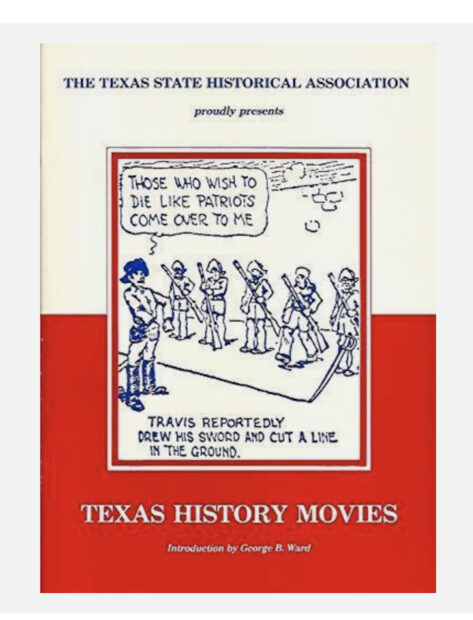

Texas History Movies, a deeply racist comic strip, was the pedagogical successor to Pennybacker, providing “for many students the first and only taste of Texas history” (New Texas History Movies, n.d.). It began in the Dallas Morning News in 1926, and, reprinted as a book, it was distributed free of charge to Texas schoolchildren by the Magnolia Petroleum/Mobile Oil Company from 1932 to 1959. Complaints that it demeaned Indians, Mexicans, and African-Americans caused Mobil to cease distribution (Brear, 1995: 166-67, n. 2; Markstein, 2010).

A skeptical examination of myths associated with the Alamo follows.

THE TEXIAN OCCUPIERS OF THE ALAMO WERE DETERMINED TO FIGHT TO THE DEATH, RATHER THAN SURRENDER.

According to Mexican Lt. Colonel José Enrique de la Peña, Texian Colonel William B. Travis acceded to the will of the garrison after days of pleading: if no reinforcements came on March 5, they would attempt to surrender or escape the next night. His sources were a San Antonian woman and a “Negro [Joe] who was the only male who escaped.” De la Peña says these accounts were later confirmed by women who remained inside the Alamo during the battle (Long, 1990: 231-32; Hardin, 1994: 137; de la Peña, 1975: 44). Mexican General Vincente Filisola says Travis, “through the intermediary of a woman,” attempted to surrender around nightfall on March 5, with the sole condition of guaranteeing their lives, but Santa Anna would only accept unconditional surrender (Long, 1990: 232; Hardin, 1994: 137). Lindley (2003: 146-47) believes Juana Alsbury was the messenger/intermediary.

De la Peña speculates that Mexican President and General Antonio López de Santa Anna thought a bloodless victory would lack “sensation” and “glory” (Hardin, 1994: 137; de la Peña, 1975:45). Perhaps more importantly, Santa Anna expected that Travis would soon receive reinforcements. Santa Anna attacked before dawn on March 6 to catch the occupiers by surprise and to prevent their escape that night. This attack also negated the Texian’s strategic advantages: long-range rifles and perhaps the most formidable array of cannon between Mexico City and New Orleans.

Until the bitter end, Travis and the garrison as a whole expected substantial Texian reinforcements. Moreover, Travis mistakenly thought that local Tejanos would overwhelmingly rally to his cause. Travis angrily recognized his error on March 3: “The citizens of this municipality are all our enemies except those who have joined us heretofore” (Hutton, 1995: 18; Tucker, 2010: 99). Many Tejanos, of course, simply did not want to take sides in this conflict. As Paul D. Lack (1992: 183) points out: “Almost any behavior, even that designed to protect themselves from the ravages of war, made the Tejanos seem like traitors from the perspective of one army, if not both….”

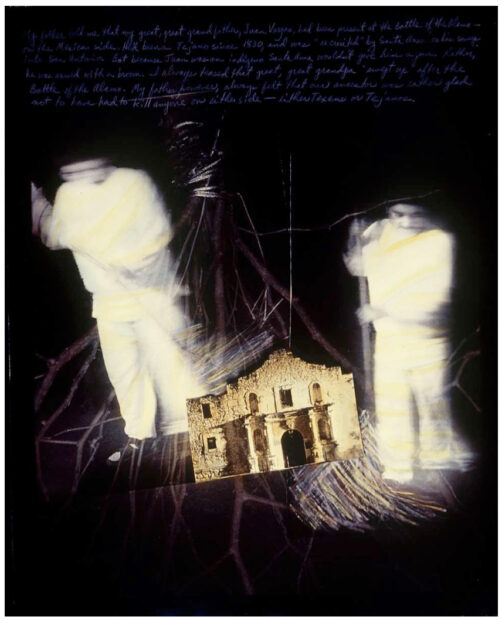

Kathy Vargas, “My Alamo,” image 1a, hand-colored silver gelatin print, 20 x 16 inches, courtesy of Gil Cardenas. Photo: courtesy of the artist. Impressed into Santa Anna’s army, Juan Vargas, the artist’s great-great-grandfather was provided with a broom instead of a rifle. She imagines that his military service consisted of sweeping the environs of the Alamo church. This work was in “The Other Side of the Alamo” exhibition at the Guadalupe in 2018.

In the March 3 letter, Travis vindictively called for the punishment of the Tejanos in San Antonio who had not united with him, which of course was virtually the entire population: “… those who have not joined with us in this extremity, should be declared public enemies, and their property should aid in paying the expenses of the war” (Hutton, 1995: 18). On June 21, 1836, after the Texians had won the war, Juan Seguín attempted — with little success — to evacuate San Antonio, telling the populace to move to the interior with their livestock, or face being “treated as real enemies… without fail” (Ramos, 2008: 169), essentially ratifying Travis’s equation of neutrality with Toryism (Lack, 1992: 181-82).

In any case, once the Texians were surrounded in the Alamo, they had few choices: they could stay put, sneak out in small numbers, or attempt a great escape. A few couriers could and did leave the fort on horseback, and the Tejanos were formally offered amnesty. But for most of the garrison, “the Alamo was as much prison as fort” (Davis, 1998: 555).

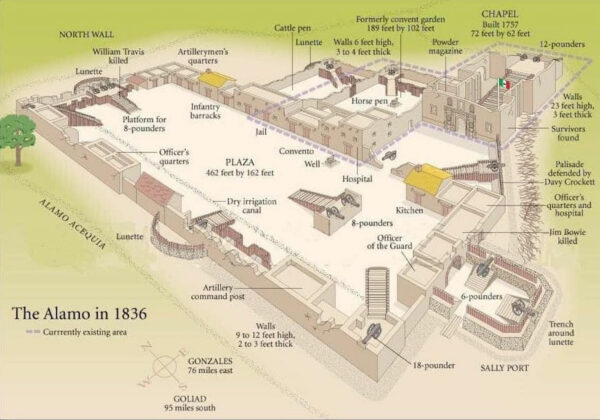

THE ALAMO HAD BEEN TRANSFORMED INTO A FORMIDABLE FORTRESS, AND IT WAS STRATEGICALLY VITAL

De la Peña deemed the Alamo “unimportant, politically or militarily,” which he says was the “unanimous opinion of all the military” (Tucker, 2010: 86, 185, 133). Ramón Martínez Caro, Santa Anna’s personal secretary, called it “a mere corral and nothing more” (Tucker, 2010: 102).

Stephen L. Hardin (1994: 131) and others have emphasized that the Alamo’s perimeter — nearly a quarter mile in length — rendered it “indefensible” without a significantly more numerous force. Tucker says it was a mistake for the Texians to defend it, and “a greater folly” for Santa Anna to attack it (2010: 133), since neither the Alamo nor San Antonio had strategic importance. Hardin (1994: 185) calls the attack on the Alamo “pointless” and “wasteful.” William C. Davis says Santa Anna had no reason to fear 200 Texian soldiers in “a mud fort,” and he should have left them behind (1998: 555).

Several authors say the Alamo was deficient or lacking in critical features possessed by purpose-built forts, such as catwalks behind the walls, firing platforms, rifle slots, portholes, bastions, ravelines, interior redoubts, hornworks, embrasures for cannon, etc. (Tucker, 2010: 84, 105, 109, 210; Hardin, 1994: 128; Long, 1990: 183). Tucker says garrison members didn’t want to work on fortifications because they were aspiring Southern gentlemen and considered hard labor to be slave work (2010: 131-32).

In a letter to Sam Houston dated January 18, G. B. Jameson, the Alamo’s engineer, complained: “the men I have will not labor…. The officers of every department do more work than the men.” Jameson lacked the time, tools, economic resources, and willing manpower to realize more significant improvements. Consequently, “most” of the Alamo’s defenses at the time of the 1836 battle had been put in place under Mexican General Cos in the fall of 1835 (Nelson, 1998: 46-47). Another problem was that many — including Travis — seem to have been more interested in fandangos than fortifications.

More recently, renowned battle illustrator Gary S. Zaboly (2011: S1-S46), argues that the extent of the Alamo’s defensive features during Santa Anna’s siege has been seriously underestimated, due to an over-reliance on post-battle illustrations that reflect the destruction of its fortifications in May of 1836, when General Juan José Andrade fulfilled his order to “render them useless for all times and under any circumstances.” Zaboly’s use of early sources leads him to conclude that the Alamo formerly “brimmed with… batteries, ramps, tambours, palisades, traverses, bonnets, battlements, embrasures, ditches, banquettes, and so on,” and thus was not the “broken-down, armed hacienda” that is commonly depicted (2011: S4, S7).

In any case, regardless of the improvements made to the former mission, it had too many vulnerabilities and too small a garrison to withstand Santa Anna’s attack for any appreciable amount of time. Travis was naïve to claim that he could hold the Alamo with 200 men, as he did in a letter on February 12 to Governor Smith (Tucker, 2010: 210). Jameson was likewise naïve to think that the Texians could “whip [the Mexican army] 10 to 1” (Nelson, 1998: 46). But — as we shall see at San Jacinto — the Texians did not possess a monopoly on hubris.

THE ALAMO WAS THE SITE OF AN EPIC SIEGE, FEB. 23-MARCH 6, 1846

“The Siege of the Alamo,” anonymous print. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. Note how the Texians are fighting under an American flag on a non-existent roof, behind the non-existent gable. The battle seems to have been collapsed into or re-imagined as a struggle for the church structure, which Mexican soldiers are scaling, as if it were part of the exterior walls. This battle is presented as a defense of the U.S. from foreign aggression.

Tucker says the Battle of the Alamo, “perhaps the most glorified battle in American history,” was “transformed into something that it was not: a climactic, epic clash of arms” (2010: 328). He calls the siege “something of a farce” because the Mexicans, who were awaiting the arrival of their large cannon (two 12-pounders that would have devastating effects), used an inadequate number of small, antiquated field pieces, which were largely ineffective (Tucker, 2010: 169, 171-72). The Mexicans generally stayed out of rifle range, and the Texians even quit returning cannon fire due to a critical shortage of usable powder.

Filisola said bombardment by twenty properly placed artillery pieces would have reduced the walls to “rubble” in less than an hour (Hardin, 1994: 129). Nonetheless, the Mexican forces dug protective trenches for their artillery and inched closer day by day. The bombardment of the north wall possibly facilitated the ability of the Mexican soldiers to scale it without ladders, though the failure to cover General Cos’ log reinforcements with an earth facing was probably a bigger factor (Long, 1990: 184).

On March 9, Captain John Sowers Brooks at Goliad wrote of a battery whose “every [cannon] shot goes through it as the walls are weak” (Zaboly, 2011: S8). Lindley (2003: 147) assumes his source was James A. Allen, Travis’ last courier, who departed for Goliad on the evening of March 5. Alan C. Huffines (1999) provides a valuable, day-by-day documentary chronology of the siege as chronicled by participants, eyewitnesses, and purported eyewitnesses.

THE STORIED BATTLE OF THE ALAMO IS ONE OF THE GREATEST “LAST STANDS” IN AMERICAN HISTORY

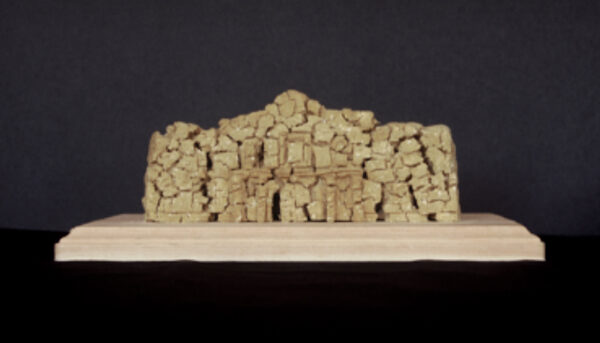

Rolando Briseño, “MasAlamo,” 2004, masa (corn dough), 3 x 4 x 5 inches, courtesy of the artist. Photo: courtesy of the artist. Briseño’s title is a pun on masa: corn dough, which he calls “the basis of Mexican civilization.” Masa is utilized to reclaim the Alamo’s Mexican origins. “MasAlamo” also literally means “more Alamo.” This work will be featured in “Dining with Rolando Briseño: A Fifty Year Retrospective” at Centro de Artes in San Antonio in 2024-2025.

While the battle is assuredly storied, the Mexican army had reached the walls before most of the Alamo occupiers were awake, much less aware that the assault had begun. William Fairfax Gray, in a diary entry on March 20, 1836, summarized the testimony of Joe, Travis’s slave, before the Texas cabinet: “when the attack was made, sentinels and all were asleep, except one man, Capt. —– [J. J. Baugh], who gave the alarm. There were three picket guards without the fort, but they, too, it is supposed, were asleep, and were run upon and bayoneted, for they gave no alarm. Joe was sleeping in the room with his master when the alarm was given” (Gray, 1997: 128).

De la Peña (1975: 52), an eyewitness, said the battle lasted an hour “before the curtain of death covered and ended it” just after 6 a.m. Santa Anna’s chief of staff, Colonel Juan Nepomuceno Almonte, says the units took their battle stations at 5:00 a.m., began the attack at 5:30, “and continued until 6:00 a.m.” (Lindley, 2003: 148). He adds: “When the enemy attempted in vain to fly, they were overtaken and put to the sword….” (Lindley, 2003: 148).

Henry Arthur McArdle, “Dawn at the Alamo,” 1905. Photo: Library of Congress. This depiction of heroic Texian resistance and Mexican perfidy is displayed in the Texas State Capitol’s Senate Chamber, in Austin, Texas. It is more grandiose than the first version from 1875, which, along with McArdle’s “Lee at the Wilderness,” was destroyed in an 1881 fire.

Tucker concludes that the majority of the Alamo garrison offered “little or no resistance” (2010: 237) and that the battle inside of the Alamo lasted only twenty minutes (2010: 318) or one-half hour (2010: 299). Davis (1998: 570) estimates that the battle took “less than an hour,” as does Crisp (2005: 64). Ironically, Tucker says the “stiffest resistance,” the “principal ‘battle’—the real last stand” took place not on the walls, but rather near the hospital, where perhaps 50-75 men who were recuperating were trapped and had little chance to escape (2010: 248-50).

According to Tucker, those Texians who had the chance to escape made the most of their opportunities in three groups: (1) 62 men escaped near the palisade just South of the church in what might have been an organized flight (2010: 261); (2) the second group consisted of about 50 men who exited the main gate on the South end (2010: 287-95); (3) a small number of men exited the Alamo near the center of the West wall (2010: 295-98). These escapees totaled as many as 120 men in Tucker’s estimation (2010: 302). They were met by 400 elite mounted lancers and cavalrymen, who mowed nearly all of them down. Thus it was more a slaughter than a fiercely contested battle. Santa Anna consequently had the Texian bodies burned in proximity to where they fell (Tucker, 2010: 304; Davis, 1998: 736, n. 105).

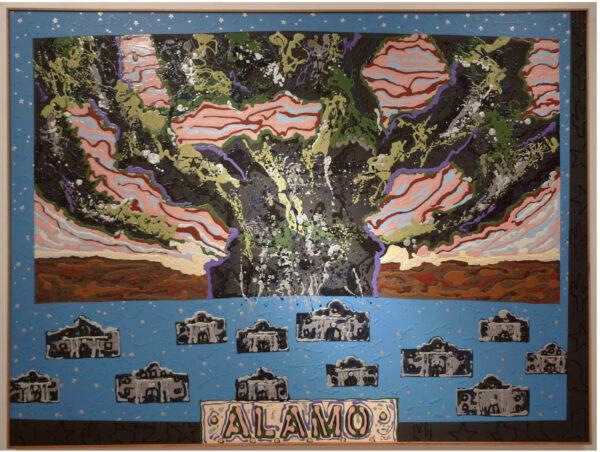

Mel Casas, “Humanscape 147 (Alamo),” 1987, acrylic on canvas, 6 x 8 feet, Casas Family Collection. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova. “Alamo” means cottonwood in Spanish, so Casas depicted a semi-abstract cottonwood tree with self-seeding miniature Alamos, like those sold in the Alamo’s gift shop. He viewed the Alamo as “fake patriotism based on fake history.” This work was in “The Other Side of the Alamo” exhibition at the Guadalupe in 2018.

Tucker (2010: 307-8) notes that Alan C. Huffines (1999: 176-77), Gary S. Zaboly, and Roger Borroel have posited substantial flights from the Alamo. Borroel (1989: 83-85) believes over 100 Texian soldiers exited the Alamo during the battle. Davis (1998: 562; 736-37, n. 105) also posits three separate escapes, and notes “perhaps a score” of known but largely ignored sources that attest to Texian soldiers escaping from the Alamo during the battle. Davis discovered a confirming report by General Ramírez y Sesma in the Mexican military archives in Mexico City, and he also mentions a confirming forthcoming publication (by other authors) of an anonymous journal of a Mexican soldier. Davis thinks as many as 80 men, who, by his estimation, constituted about a third of the Texian force, fled the Alamo during the battle. Tucker concludes that the majority of the Texian garrison died outside of the Alamo and “even farther from the romance and glory of the mythical last stand” (2010: 308).

THE TEXIAN OCCUPIERS OF THE ALAMO WERE ANGRY THAT SANTA ANNA HAD USURPED THEIR RIGHTS AS COLONISTS

Walter Lord (1968: 20) estimates two-thirds of the garrison were “new arrivals” from the U.S., and, apart from a handful of Tejanos, only six were residents of Texas for six years or more. He concludes that the Anglo-Americans at the Alamo “weren’t fighting for any kind of Mexican constitution” (1968: 20). Hutton (1995: 20) says: “Almost all of them were recent emigrants to Texas, and it was unlikely that many of them knew anything about the Mexican Constitution.” Tucker avers that the Alamo occupiers were “almost wholly recent volunteers from the United States” who entered Mexico illegally, seeking free land that belonged to Mexico (2010: 15). Hardin (1994: 137) notes: “the majority had only recently come from the United States. … Few of the real Texians were there, for few of the old settlers had originally sought independence or war.” De la Peña (1975: 51) wrote in his diary: “there were thirty or more colonists, the rest were pirates.” Lack (1992: 110-36) provides a comprehensive study of the Texian army, complete with charts that provide a basis for Kelley’s summary below (115, 123, 127).

Michael G. Kelley summarizes the three phases of the Texian army: (1) in the earliest phase, 63 percent of the men who fought at Gonzalez and San Antonio in late 1835 had spent at least a year in Texas, and fourteen percent were in Texas for eleven years or more. After the December 1835 capture of San Antonio, most Texas colonists who had participated in the revolt returned home to tend to their crops. (2) 78 percent of the soldiers during the Alamo and Goliad campaigns in 1836, by contrast, had spent less than four months in Texas, and only four percent had been in Texas for at least 11 years. (3) At the Battle of San Jacinto, 24 percent of the men in the army had been residents of Texas for at least six years, while only 21 percent had lived in Texas for less than five months (Kelley, 2011: 200-01). Nonetheless, that means at least 38 percent had been in Texas for a year or less, not including those combatants who left no documentary trace.

Long (1990: 109) notes “two waves of mercenaries,” the first of which arrived about the time San Antonio was captured, and the second after San Jacinto. The first group was largely killed before San Jacinto. Thus the happenstance that a quarter of the soldiers at San Jacinto had relatively deep Texas roots was an anomalous statistical blip.

Even in the earliest period of the revolt, U.S. citizens served critical roles. The newly arrived New Orleans Greys were instrumental in the capture of San Antonio and the Alamo in the first place: without them, the revolt would likely have collapsed in late 1835 (Brown, 1999: 46; Tucker, 2010: 89). Gary Brown (1999:88) says the attack “was launched almost entirely by United States volunteers led by American officers and wielding American-manufactured weapons and equipment.” Whether or not this characterization is an overstatement, the participation of U.S. volunteers was vital, nonetheless. Given the relatively few colonists in San Antonio in December of 1835, Brown concludes: “there is reason to doubt that the army remaining there was fighting for the constitutional freedoms of the Anglo settlers” (1999: 88).

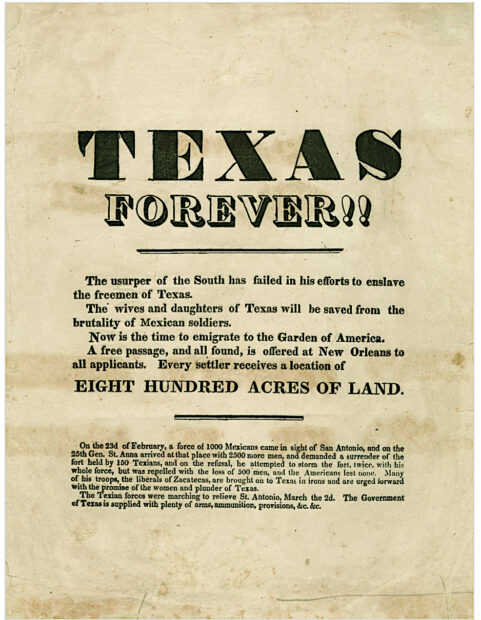

“Texas Forever” leaflet (reproduction). Photo: Copano Bay Press. Likely printed between March 17 and March 28, 1836 in New Orleans, this leaflet declares: “The usurper of the South [Santa Anna] has failed in his efforts to enslave the freemen of Texas. The wives and daughters of Texas will be saved from the brutality of Mexican soldiers.”

In an 1836 speech in the House of Representatives, John Quincy Adams mocked the grounds adduced for the revolt in Texas by saying the state of Michigan “has greater grievances and heavier wrongs to allege against you for a declaration of her independence, if she were disposed to declare it, than the people of Texas have for breaking off their union with the Republic of Mexico” (Lundy, 1837: 35). Paul D. Lack (1992: 3-4) observes: “The people of Texas had received much from the government of Mexico and had not been badly treated…. Seldom has the ruling hand been felt so lightly as in Texas in the period 1821-35.” Josefina Zoraida Vázquez (1997: 75) declares: “No group in Mexico received as many privileges as the Texans because the government was determined to make the colonization work.”

While the complaint made by the colonists of the future U.S. was “no taxation without representation,” the Texian colonists long had representation without taxation (since tariffs were waived, generally for seven years).

Frederick Merk concludes: “The explanation of the Texas revolution, that it was an uprising against Mexican tyranny, is unfounded. That explanation was propaganda, spread by the Texans in the course of the war. … But even Texas historians now agreed that Mexican rule had not been cruel or oppressive. The revolution was basically the outcome of admitting into the rich prairies of Texas a race of aggressive and unruly American frontiersmen, a masterful race of men, who were contemptuous of Mexico and Mexican authority” (Merk, 1972: 180).

THE TEXIAN OCCUPIERS OF THE ALAMO WERE A FORMIDABLE FIGHTING FORCE

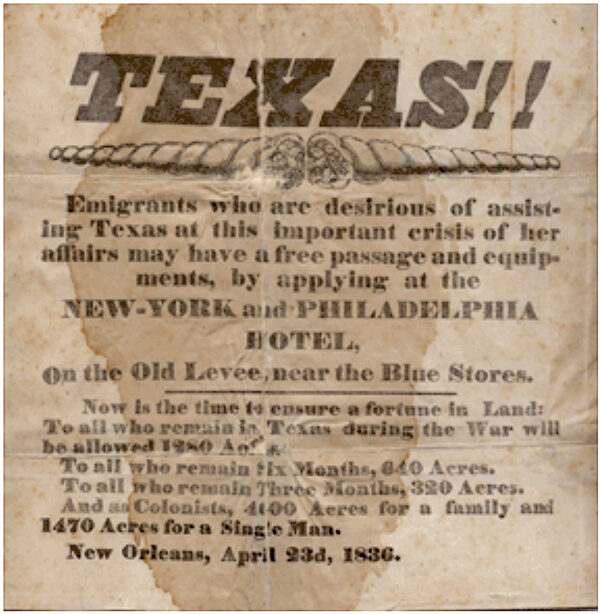

“Texas!!” April 23, 1836, New Orleans. This handbill offered “a fortune in land” for “emigrants… desirous of assisting Texas at this important crisis of her affairs.”

In Texas, it is commonly asserted that Travis’ men made up one of the finest fighting forces of its age, if not in the history of the world. Walter Lord (1968: 20) debunks the notion that the garrison was mostly made up of “frontier types” like those found in Western films. He characterizes them as a “cross section of the America of that period,” without a single professional soldier. In contrast to the misconception that a high percentage of the Texian occupiers were frontiersmen skilled in warfare with the legendary long rifle, Lord (1968: 20), Tucker (2010: 145), and Walraven (1993: 59) note their many professions: lawyer, merchant, farmer, rancher, clerk, surveyor, bricklayer, blacksmith, hatter.

They had so little military experience that Tucker refers to them as “amateurs under arms” (Tucker, 2010: 263). De la Peña describes them as “inexperienced and untried in the science of war” (Tucker, 2010: 263). During the war, Texas offered 1,200 acres for military service, an additional 640 for completing six months service, and an additional 4,444 for settling with a family (Tucker, 2017b: 104).

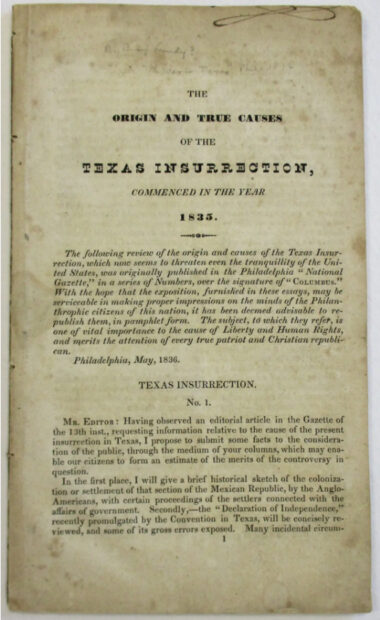

Benjamin F. Lundy, “The Origin and True Cause of the Texas Insurrection, Commenced in the Year 1835,” first edition, 1836. Photo: Biblio.

Benjamin F. Lundy condemned these mercenary “bribes” for military service: “The artful deceivers, however, have not relied upon the generosity and noble sympathy of our fellow-citizens, for they insidiously presented a bribe to excite their cupidity also. They have not only falsely represented the Texian cause as one of pure, disinterested liberty and justice, as opposed to perfidious tyranny and cruel oppression, but they have themselves assumed something more than the liberty which they basely and hypocritically advocate, by impudently promising a fertile paradisiacal piece of Texian land, a mile square, to every American citizen and foreign emigrant, who will sally forth to capture it from the Mexican republic!” (Lundy, 1837: 33).

Widely posted handbills lured enlistees to Texas with the promise of “a fortune in Land” (Tucker, 2017b: 105). [See illustration above.] When prime cotton-growing land was auctioned for as much as $50 an acre in the U.S., this was no exaggeration. It should be no surprise that many of the men who had braved long and perilous journeys in order to receive free land were poor farmers or ranchers. Since an individual worker could cultivate only eight to ten acres, the remainder of the property could serve as an investment, thus all settlers could be regarded as potential land speculators (Torget, 2015: 84-85).

THE TEXIAN OCCUPIERS OF THE ALAMO MADE THE MEXICAN ARMY PAY DEARLY FOR ITS VICTORY

Alamo Battle Miniature, Texas Military Forces Museum. Photo: Texas Military Forces Museum. On its X (formerly Twitter) account, the Texas Military Forces Museum notes the many inaccuracies of this tableau

Recent estimations of Mexican casualties are much lower than those that have long prevailed. On April 12, 1836, the New York Herald estimated that the Mexican army had suffered between 2,000 and 3,000 killed and wounded at the Alamo (Tucker, 2010: 309). On the same day, the Memphis Enquirer declared that 1,600 Mexicans had been killed, citing Travis’s slave Joe as its source (Tucker, 2010: 310). Pennybacker’s Texas textbook (1888: 78) also enumerated 1,600 Mexican fatalities. T. R. Fehrenbach (1968: 214), in his immensely popular Lone Star: A History of Texas and Texans, accepted the figure of “nearly 1,600 Mexican dead.”

In pointing out the absurdity of these figures, Tucker (2010) and Jeff Long (1990: 243-45) emphasize that the Texians were caught by surprise; their guns could not have fired properly if they had been loaded the previous evening; and they suffered severe shortages of usable gunpowder, ammunition, and cannon balls. Tucker believes a majority of the garrison sought to escape. He says the most accurate count was that of Santa Anna’s chief of staff, Colonel Almonte, who, on March 6, listed 65 killed and 223 wounded in his Order Book (Tucker, 2010: 318). Tucker notes the similar figures given by other Mexican officers (2010: 317-18).

Davis says the number of Mexican soldiers killed in the battle is “unclear.” He thinks 400 were wounded (based on hospital figures that would include those wounded in the siege, adjusted for a number that remained hospitalized from 1835 campaign), 75 of which subsequently died. Davis estimates about 200 Mexican soldiers were killed or mortally wounded based on Mexican accounts (1998: 569-70; 739-40, n. 22).

Lindley (2003: 275) gives a total of 516 killed and wounded, including during the siege, which is very close to Davis’s total. Richard Bruce Winders (Collins, 2012: xiii) says historians currently accept a figure of less than 400 killed and wounded Mexican soldiers. According to Ramón Martínez Caro, who was Santa Anna’s secretary, the Mexican death toll was needlessly compounded by Santa Anna’s callousness and lack of medical preparedness, which resulted in over 100 deaths from wounds that should not have been fatal (Hardin, 1994: 155).

Tucker believes that half or more of Mexican casualties came from “friendly fire” (2010: 312-315). Many were shot from behind as they scaled or descended the walls. Mexican soldiers were generally not trained marksmen — they marched in columns and shot from the hip in volleys, and many must have shot their fellow soldiers in the darkness, tumult, and confusion. General Filisola attributed “most of our dead and wounded” — more than three-quarters — to friendly fire (Long, 1995: 245-46; Tucker, 2010: 313). Hardin (2001: 41) says Filisola’s percentages might be “exaggerated.”

Lajos Markos, “The Siege of the Alamo,” 1975, oil on canvas, Texas State Capital, Austin. Photo: eBay. The Texas capital has a penchant for grandiose, inaccurate illustrations of the battle.

De la Peña (1975: 54) said 253 Texian bodies were counted. Almonte (Lindley, 2003: 148), Sanchez-Navarro, and an anonymous source in the newspaper El Mosquito Mexicano also listed the body count in the 250s (Edmondson, 2000: 408). The most commonly used figure is only about 182 bodies, a figure used by Ruiz (who probably wasn’t even in San Antonio at the time of the battle), which is identical to Caro’s 183, minus Gregorio Esparza, who was permitted burial (Edmondson, 2000: 408). In a notation, de la Peña lists the conventional numbers of those thought to be in the Alamo: 150 volunteers, 32 inhabitants of Gonzalez, and “and about 20 or so townspeople or merchants” from San Antonio (de la Peña, 1975: 54, n. 17).

Tucker speculates that when Travis cited 150 men (a figure subsequently increased by the approximately 32 men from Gonzalez), he might only have been counting able-bodied men (2010: 319). Davis thinks Travis did not count either the sick or the Tejanos (1998: 548) and the total number of garrison members could have been “240 to 260 or more” (737, n. 105). In his January 18 letter to Houston, Jameson tallied 80 “effective” men out of a total of 114, which means about 35 were sick or wounded at that time (Nelson, 1998: 46). Crisp (2005: 144) notes “200-odd defenders.”

Other researchers speculate that the Alamo garrison received additional, hitherto unaccounted for reinforcements. But where could such a substantial number of ghost riders have come from, without leaving a trace, or being spotted by the encircling Mexican forces? Lindley (2003: 119-171) has some theories.

I see one way to explain how two groups of people could come up with two distinct, but relatively similar body counts: one group of counters missed one group of bodies, or one group of counters double-counted one group of bodies. Bodies in the Alamo, for instance, could have been counted on the inside, and then counted again after they were taken outside to be burned. In any case, scholars are increasingly favoring the higher number.

THE TEXIAN OCCUPIERS OF THE ALAMO REPRESENTED AND FOUGHT FOR THE ANGLO-AMERICAN COLONISTS (THE “OLD TEXIANS”) WHO DECLARED INDEPENDENCE FROM MEXICO

1824 Flag (replica). Photo: Gallery of the Republic.com. Captain Philip Dimmitt described the flag he designed in October 1835 (which does not survive) as one of Mexican colors with “Constitution of 1824” written in the center. In the early days of the revolt, a tri-color flag with the date 1824 served as the Texian flag (along with other flags).

Independence was not declared until March 2, 1836, and neither the Texians nor the Mexicans at the Alamo had confirmation of this event. The convention that declared independence at Washington (subsequently called Washington-on-the-Brazos) consisted of 59 delegates, almost half of whom had been in Texas less than two years. The declaration itself, which was modeled largely on the U.S. Declaration of Independence, was written by the nephew of a land speculator. Its author, George C. Childress, had spent only a few months in Texas: he likely wrote the declaration in Tennessee, where he met with President Jackson (who had his tentacles everywhere) shortly before leaving for the convention (Shuffler, 1962: 327-29; Campbell, 2003: 147).

Almost a third of the delegates had lived in Texas less than six months, and only one delegate was from Austin’s original colony. 29% arrived after the war had begun. Only ten had been Texas residents for more than six years (Long, 1990: 207; Reichstein, 1989b: 77). The Declaration, signed largely by interlopers who had no authorized right to be in Mexico, reflected these shallow roots. It complained of the loss of rights “habituated in the land of their birth, the United States of America” as well as the fact that legislation was conducted “in an unknown tongue” (i.e. Spanish) (Long, 1990: 208). It was quickly and unanimously adopted in an unfinished house that no longer survives, though a “battered chest” (14 x 22 x 10 inches) constructed of planks from this hallowed hall rests in the State Archives. It is known as The Ark of the Covenant of the Texas Declaration of Independence (Shuffler, 1962: 314-17, 327-29, 331).

The Ark of the Covenant of the Texas Declaration of Independence, oak boards from building, veneered walnut from a desk, 14 x 22 x 10 inches. Photo: Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

The Alamo garrison expected that independence would increase the value of slaves as well as land. David P. Cummings, a Texian who would die at the Alamo, wrote in a letter dated February 14, 1836: “upon the faith in this great event [independence] great speculation is going on in Lands….” (Tucker, 2017b: 101). Cummings noted: “The price of land has risen greatly since the commencement of the war….” (Tucker, 2017b: 31).

By the time the Battle of the Alamo approached, most legitimate colonists had returned to their homesteads. Moreover, Tucker says the occupiers of the Alamo did not sufficiently appreciate that they were “the natural opponents of the older [Anglo-American colonist] settlers” for Texas land (Tucker, 2010: 89). The newcomers at the Alamo supported complete independence from Mexico, which would potentially threaten the land grants of the “Old Texians,” the certified colonists, who supported the 1824 Mexican Constitution.

The latter did so because the 1824 Constitution, which did not mention slavery, deferred the issue to individual states. Erasmo Seguín represented Texas in Mexico City when the Constitution was being written, and he “helped insure” that it did not forbid slavery” (Torget, 2015: 79, 78, 256; Tucker, 2017a: 58-59). Andrew J. Torget (2015: 71) calls Erasmo Seguín a “fierce advocate” for slavery in Texas. As Torget (2015: 174) also points out, by 1836, federalism in Texas and slave-based agriculture “could not be separated.” The defense of federalism in Texas meant the defense of slavery, for they were intertwined from the inception of the 1824 Constitution. Andreas Reichstein (1989b: 72) argues that claiming fealty to the 1824 Constitution was also a stratagem designed to “enlist more aid from the U.S. … [and] the support of the liberal Mexicans and thus divide Mexican opinion.” Reichstein (1989b: 72) adds that all the delegates to the Consultation knew “they were actually fighting for independence,” and they had no intention of keeping the pledge they had sworn to the Mexican federation.

The Alamo garrison did not recognize the authority of Texian General Sam Houston (Lack, 1992: 119; Hardin, 1994: 58), and they received no support from him (Tucker, 2010: 133). Houston, who had advised against occupying the Alamo, claimed not to believe Travis’ desperately worded appeals for aid and reinforcements (Davis, 1998: 547-48, 568-69; Kelley, 2011: 189-190; Tucker, 2010: 167). Travis, James Bowie, and David Crockett were among Houston’s greatest potential political rivals for leadership in a new state or republic: their deaths served to eliminate his chief competitors. Moreover, Crockett was a champion of the “common man,” rather than the wealthy planters and land speculators, as well as an ardent foe of President Andrew Jackson (Tucker, 2010: 115-17). In any case, Houston was too canny to allow himself to be trapped in the Alamo, and that reticence might have a bearing on his dilatory rescue effort, once he decided to head in the Alamo’s direction.

SLAVERY WAS NOT A PARAMOUNT FACTOR IN THE TEXIAN REVOLT

Rolando Briseño, “Tipping San Antonio” (a.k.a. “Spinning San Antonio,”) as performed in front of the Alamo church, 2011. Photo: courtesy of the artist. Drawing on folk Catholicism, Briseño has fashioned a kinetic sculpture in which either the saint (San Antonio) or the Alamo is upside-down — and is thus being punished. The work addresses many issues, including slavery and the role of Tejanos at the Alamo. This work was in “The Other Side of the Alamo” exhibition at the Guadalupe in 2018, and it will be on view in “Dining with Rolando Briseño: A Fifty Year Retrospective,” at Centro de Artes in 2024-2025.

Though slavery is the most repressed factor in Texas history — an issue that will be addressed in detail in a later essay — a number of works in recent decades have underscored slavery’s importance in the Texian Revolt. Paul D. Lack (1985: 190) points out that federalism “tacitly protected slavery,” despite repeated condemnations by the national government. “Clearly, the challenge to slavery contributed to the Texas decision to resist the new order [centralism] in Mexico” by force of arms in 1835, says Lack (1985: 190), who adds that separation from Mexico “also promised to end the period of disputation on the status of slavery.” Lack (1985: 187) also notes: “Even malleable local Mexican officials clearly regarded slavery as a temporary and shameful evil,” and by the spring of 1835 there were ample “warnings that traditional Mexican restraint with regard to slavery had come to an end.” Moreover, by the summer of 1835, “many Anglo Texans concluded that Mexico had acquired the will and power to implement an antislavery strategy” (Lack, 1992: 241).

Vázquez (1997: 76) points to the extensive protections for slavery that were built into the Republic of Texas constitution (such as: “Congress shall not pass laws to prohibit bringing their slaves into the Republic…. nor shall Congress have power to emancipate slaves….”) as tangible evidence of “the significant role that Mexico’s antislavery stance” played in Texan independence.

Slavery was the king of the Texas constitution, relegating congress to second fiddle. The British Plenipotentiary Minister in Mexico reported on June 1, 1836 that Irish colonists who left San Patricio for asylum in Matamoros told him “the establishment of slavery as a permanent institution was one of the principal causes of the rebellion” (Vázquez, 1997: 76).

Quintard Taylor (1998:39) argues: “The Texas Revolution of 1835-36 is often represented as a contest between liberty-loving Anglos and Tejanos confronting a despotic Mexican government. That image belies a central motive in the campaign for independence: an Anglo desire to preserve slavery.”

Will Fowler (2007: 163) writes: “as long as the federal 1824 Constitution was in place slavery was allowed to continue under Texan law.” He points out, however, that “the imposition of a centralist state would result in the abolition of slavery,” which he calls “one of the main, yet often downplayed, reasons why the Texans rose up in arms” (2007:163). Fowler (2007: 175) adds: “after the demise of the 1824 charter, there were no longer any legal loopholes whereby slaves could be legitimately kept in Texas.”

Kristel A. Orta-Puente, Heroes of Texas Slavery Series-El Empresario [Stephen F. Austin], 2018, digital print, 14 x 11 inches. Photo: courtesy of the artist. Orta-Puente has depicted Texas “heroes” explicitly in their function as “heroes of slavery,” imagined as trading cards with bullet-riddled backgrounds. This work was in “The Other Side of the Alamo” exhibition at the Guadalupe in 2018.

Tucker deems slavery “the true—but most forgotten, denied, and overlooked—catalyst of the Texas Revolution” (2017a: 3). Tucker sees this struggle as a component of a “national war for slavery” rather than the “localized grass roots revolt” found in Texas histories, due to the “massive” neutrality law-violating, multi-level involvement of the United States, particularly in the South (2017a: 16).

He also points out that the exclusive focus on the Alamo occupiers ignores the desire for freedom on the part of 5,000 black slaves, a reality “silenced to preserve… the Texas creation story” (Tucker, 2017a: 18). A number of Alamo garrison members owned slaves, and, according to Joe, other slaves were inside during the battle (Jackson, 1998; Durham, 2005).

Tucker argues that President Andrew Jackson and Southern planters formed a “pro-slavery cabal” to expand slavery (2017a: 22-25). Tucker says that Houston, whom he calls Jackson’s “political-military representative,” was sent by Jackson in 1832 to prepare the groundwork for a pro-slavery revolt in Texas (2017a: 209; 191; 197-204). In a report Houston sent to Jackson on February 13, 1833, he noted that nineteen out of twenty Texians wanted annexation by the U.S., and that Mexico was “powerless and penniless,” embroiled in civil war, and thus unable to keep Texas (Stenberg, 1934: 242; Tucker, 2017a: 200-01). Houston and Jackson subsequently conferred in Washington D.C. in the spring of 1834, according to Houston’s cousin Narcissa Hamilton, to make “plans for the liberation of Texas” (Tucker, 2017a: 217).

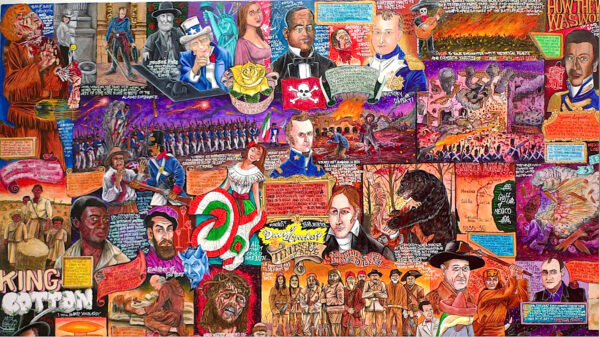

Albert Alvarez (b. 1983), “How the West Was Won” (detail), 2018, acrylic on paper collage on panel, 30 x 40 inches, courtesy of Dr. Raphael and Sandra Guerra. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova. Alvarez’s painting is a vast crazy-quilt of historic, legendary, and pop cultural images, with an equally diverse sampling of commentaries, including his own. This work was in “The Other Side of the Alamo” exhibition at the Guadalupe in 2018.

In April of 1834, Houston, who was a major land speculator, wrote to his partner James Prentiss, predicting that Texas would be a sovereign state “within one year” and “forever” severed from Mexico in three years (Stenberg, 1934: 243; Tucker, 2017a: 219). In a follow-up letter a few days later, Houston informed Prentiss that a cessation treaty with Mexico “would not be ratified by the present Senate” (Stenberg, 1934: 243), likely an expression of Jackson’s assessment. The Texians wanted virtually free land and slavery. Land was not a problem — Mexico was happy to provide it. But on the issue of slavery, Mexico and the Texians were on a collision course that — unless one side gave in — could only lead to war. Tucker concludes that the Texian Revolt, rather than the American Civil War, constituted the “first war over slavery” (2017a: 19).

Even Captain Juan Nepomuceno Seguín, the preeminent and highest ranking Tejano hero of the Texian Revolt, came from a family that owned at least one slave (one of only three Tejano families with this distinction in 1820), planted cotton, and operated a cotton gin (Ramos, 2008: 92; Tucker, 2017a: 126; Tucker, 2017b: 258). Moreover, Juan Seguín’s father Erasmo served as a close ally and cultural broker for Stephen F. Austin (Ramos, 2008: 81, 83-84, 120). The elder Seguín worked for years to oppose abolition laws and the enforcement of them in Texas, both on the national level and on the state level, and he was arguably the single most accommodating Tejano ally of slavery and Anglo colonization (Ramos, 2008: 97, 117-18; Tucker, 2017a: 126; 2017b: 258; Torget, 2015: 78-79, 256-57).

After San Jacinto, Juan Seguín led a unit charged with hunting down and capturing the slaves that had been liberated by the Mexican army (Tucker, 2017b: 258). Despite his light skin and his exemplary service to the Texian Revolt, the Republic of Texas, and the cause of slavery, Seguín was falsely implicated and hounded from Texas by death threats from new Anglo American arrivals to Texas. He fled to Mexico with his family and later fought against the U.S. in the Mexican-American War (de la Teja, 2017; Ramos, 2008: 173-77).

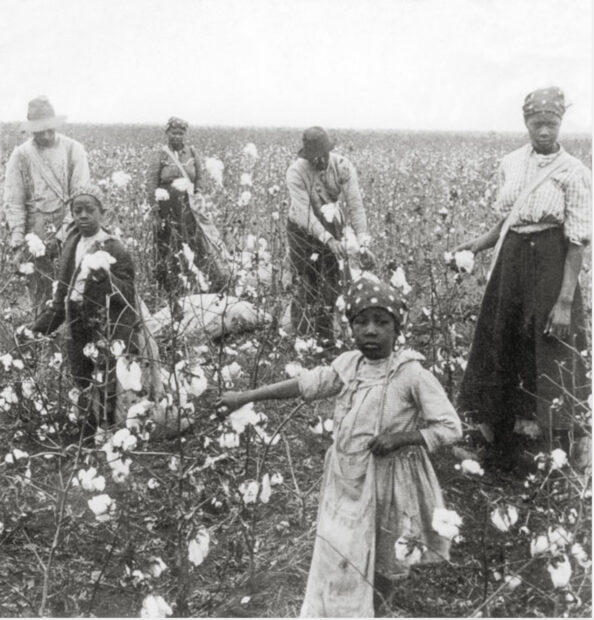

Black Sharecroppers in Cotton Field, early 20th century, Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin. Photo: Bullock Museum. After Reconstruction, Black people were frequently forced into exploitative sharecropping relationships that kept them impoverished.

Tucker supports the conclusions of Benjamin Lundy, the Quaker abolitionist who determined that slaveholders, slave traders, and land speculators sought to take Texas, re-establish slavery in it, and annex it to the United States (Tucker, 2010: 39).

ANTI-MEXICAN RACISM WAS NOT A SIGNIFICANT FACTOR IN THE TEXIAN REVOLT

Ruben Luna (b. 1974), “Available for Purchase in the Gift Shop,” 2018, mixed media, 13.25 x 44.25 x 3.25 inches, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova. Luna notes how toy weapons are marketed at the Alamo “to kids,” which serve to promote violence against Mexican Americans and their descendants. In the cartoon history textbook “Texas History Movies” (illustrated and discussed above), Texians shouted racist epithets when they shot Mexican soldiers, which encouraged Anglo schoolchildren to emulate them. This work was in “The Other Side of the Alamo” exhibition at the Guadalupe in 2018.

Reginald Horsman observes: “The Texas Revolution was from its beginnings interpreted in the United States and in Texas as a racial clash, not simply a revolt against unjust government or tyranny” (1981: 213). More significantly, Texas became the crucible of racialized Anglo-Saxonism: the “belief that American Anglo-Saxons were destined to dominate….” (1981: 208). Horsman views the Texian Revolt and the Mexican-American War as catalysts “in the adaptation of a racial Anglo-Saxonism” (1981: 209). He adds: “In the 1830s and 1840s, when it became obvious that American and Mexican interests were incompatible and that the Mexicans would suffer, innate weaknesses were found in the Mexicans” (Horsman, 1981: 210). Anglo-Americans argued that they were driven by Providence or Destiny — rather than greed or opportunism — to conquer people they considered racial inferiors, which in their minds absolved them of guilt.

Roberto Jose Gonzalez, “Una Limpia de Colón: Eres un Conquistador (A Columbus/colon Cleansing: You are a Conquistador),” 2018, 90 x 78 inches, acrylic with gold and silver leaf on canvas, courtesy of the artist. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova. Gonzalez regards the Alamo and Columbus as primary colonial/racial symbols, which are here “cleansed” by the Mesoamerican god Quetzalcoatl. This work was in “The Other Side of the Alamo” exhibition at the Guadalupe in 2018.

Stephen F. Austin is generally described as extremely tactful and diplomatic in his dealings with his host nation and its people. Many of his letters were written for public consumption, sometimes for publication. But in letters to his brother James Brown Austin, written in 1822 and 1823, he expressed scorching impressions of Mexicans from his first trip to Mexico. He called them “bigoted and superstitious to an extreem [sic],” and he noted that “indolence appears to be the general order of the day.” He further claimed that “the majority of the people of the whole nation as far as I have seen want nothing but tails to be more brute than apes” (Weber, 1988: 157). However one might want to try to rationalize Austin’s last observation, there is no taking the tail off of that trope!

Similarly, Noah Smithwick, who moved to Texas in 1827, claimed, in recollections dictated at the end of the 19th century, that he “looked on the Mexicans as scarce more than apes” (Weber, 1988: 154; Smithwick, 1983: 31). David J. Weber notes: “many Anglo-American writers held a contemptuous view of Mexican males wherever they encountered them,” but negative stereotypes were based less “on direct observation or experience” than the anti-Catholic and anti-Spanish views inherited from their Protestant forebears (1988: 159). This prejudicial heritage, known as the Black Legend, will be further explored in a future essay.

In Lundy’s opinion, “the sole object of the foreigners… is to make money; and they indulge in all the unholy prejudices against people of colour, which they brought with them, or have contracted from their associates here” (1847: 146). Many scholars see considerable racial prejudice on the part of the predominantly Southern U.S. immigrants who came to Texas. Arnoldo De León emphasizes this aspect: he argues that the initial Anglo-American colonists in Texas regarded Mexicans as “primitive beings who during a century of residence in Texas had failed to improve their status and environment. Mexicans were religious pagans, purposely indolent and carefree, sexually remiss, degenerate, depraved, and questionably human” (1997: 12). In his view, “the haunting prospect of being ruled by such people indefinitely explains in part the Texian movement for independence in 1836” (De León, 1997: 12). He calls racism “very prominent as a promoting and underlying cause” of the revolt (De León, 1997: 12).

James E. Crisp, on the other hand, views the Texian Revolt as “less a consequence of racial friction than a precipitating cause of it” (1995: 48). In any case, he is assuredly correct in concluding that “the greatest measure of oppression in Texas came not before 1836, but after” (Crisp, 1995: 48).

In generalizing about Anglo-American attitudes, Raul A. Ramos (2008: 266, n. 73) makes three points: “First, they chose not to follow Mexican laws and civic practices; second, according to Mier y Terán’s report, those Tejanos in their midst were treated poorly; and finally, many Anglo-Americans created a generalized negative attitude toward people of Mexican origin after the Law of April 6, 1830” (this law nullified unfulfilled empresario contracts, forbade the further importation of slaves, and ended immigration from the U.S. — though the Austin and De Witt colonies got exemptions). Ramos (2008: 89) says that Anglos who looked at Mexicans negatively tended to focus on the indigenous component of Mexican ethnicity in a class-based manner, which served to exempt elite Mexicans from negative stereotypes.

Reichstein (1989b: 73) deploys a surgical accusation of racism: he argues that a few men in the war party, such as Henry Smith, Branch T. Archer, and Robert M. Williamson, “detested the Mexicans as a whole” and had always wanted independence from Mexico, regardless of what form of government it possessed. He also listed Travis as one of the Texians who “basically hated and were contemptuous of Mexicans” in another publication (1989: 187). Reichstein (1989b: 73) adds that the war party, and with them “all other leading Texans who followed that group in autumn 1835… did not fight with an ideological impetus but for ethnic reasons.”

Lack (1992: 13) observes that Anglo settlers possessed “intense racial consciousness,” which led them to regard Tejanos with suspicion, though the two groups had limited contact since most of the Tejanos lived in or near to San Antonio. The exception was Nacogdoches, where the 600-strong Tejano community had constituted a majority until 1834, when their transformation to minority status “accelerated ethnic tensions” (Lack, 1992: 13). Lack (1992: 78) points out that, due to the influence of U.S. volunteers, the revolt became “more openly anti-Mexican” in December of 1835 and January of 1836. He believes expressions of prejudice had previously “been restrained by political prudence” (1992: 78). The earliest Anglo American settlers, who willingly become Mexican colonists, likely had considerably less racial animus towards Mexicans than the newcomers who clamored for war, independence, and annexation to the United States. The Texian Revolt and the Mexican-American War fanned the flames of racism.

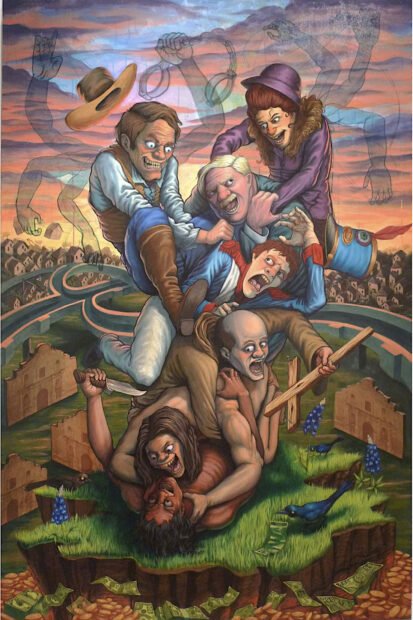

Enrique Martinez (1979), “King of the Hill,” acrylic on masonite, 2018, 71 x 47 inches, courtesy of the artist. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova. Martinez depicts the continuous struggle over land, from indigenous combatants, to Catholic priest, to Mexican soldier, to crazed Texian with shackles, to an Anglo developer, capped, finally, by a composite Alamo preservationist figure, who attempts to strangle the developer. Multiple copies of the Alamo, rendered as degraded Warholian commodities, imply the absence of originality/authenticity. This work was in “The Other Side of the Alamo” exhibition at the Guadalupe in 2018.

General Filisola notes that when Texians encountered dark-skinned Mexican soldiers, “they treated them with grossly insulting scorn as if they were dealing with their own slaves” (Tucker, 2017a: 224). After San Jacinto, Texians pressed some surviving dark Mexican soldiers into servitude/slavery, as they had after General Cos’ surrender at San Antonio in 1835 (Tucker, 2017b: 256). Torget (2015: 182-83) notes that captured Mexican soldiers were leased out as “servants” to any Anglos willing to take them. For an overview of the treatment of Mexican prisoners after San Jacinto, see Henson (1990). Prior to the Texian Revolt, free Mexican citizens had been kidnapped and sold into slavery in Louisiana; some Mexican soldiers who survived San Jacinto would have suffered the same fate, had it not been for the timely intervention of the Mexican consul (Tucker, 2017b: 256). Given the racialized discourse surrounding the Texian Revolt, John Quincy Adams rhetorically asked the most pertinent racial question in a speech in the House of Representatives on May 25, 1836: “Do not you, an Anglo-Saxon, slave-holding exterminator of Indians, from the bottom of your soul, hate the Mexican-Spaniard-Indian emancipator of slaves and abolisher of slavery?” (Lundy, 1837: 35).

As Hutton (1995: 18) observes: “the myth of the Alamo is often stunningly racist.” This is because “a creation myth draws lines of good and evil that are always razor sharp” (1995:18). He adds that as a 19th century creation, the myth “reflects the racial sensibilities of that time” (1995:18).

Joe de la Cruz, “Alamo Crackers,” 2010, ink jet on copy paper, 8 ½ x 11 inches, courtesy of Tomás Ybarra-Frausto. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova. For an elementary school Alamo pageant, de al Cruz drew the name William Barrett Travis, but he was forced to play a Mexican soldier instead, because his ethnicity was regarded as villainous. “Alamo Crackers,” a near homophone for “Animal Crackers,” is in part a response to dominant, racially exclusionary groups in San Antonio, such as Order of the Alamo and the Texas Cavaliers. This work was in “The Other Side of the Alamo” exhibition at the Guadalupe in 2018.

Tucker sees a continuation of the racial clash against Mexicans to the present day. He says a “vainglorious and heavily xenophobic” tone characterizes Texas history books, which suggests that their true purpose is to “demonstrate cultural and racial superiority over the Mexicans” (2017a: 2).

“No Dogs, Negroes, Mexicans,” Lonestar Restaurant Association sign, from Dallas, TX, National Civil Rights Museum, Memphis, TN. Photo: Adam Jones, Wikipedia.

Works Cited:

Brear, Holly B. 1995. Inherit the Alamo: Myth and Ritual at an American Shrine. Austin, Tex: University of Texas Press.

Bullock Texas State History Museum. n.d. “James Bowie’s Mexican Land Grant Application, 1830. Slave Trader turned Texas Revolution Hero requests land.” [Features scan of original document.]

Campbell, Randolph B. 1989. An Empire for Slavery: The Peculiar Institution in Texas, 1821-1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Campbell, Randolph B. 2003. Gone to Texas: A History of the Lone Star State, 2018.

Collins, Phil. 2012. The Alamo and Beyond: a collector’s journey. Buffalo Gap, Tex: State House Press.

Crisp, James E. 1995. “Race, Revolution, and the Texas Republic: Towards a Reinterpretation,” The Texas military experience: from the Texas Revolution through World War II. Joseph G. Dawson, ed. College Station, Tex: Texas A&M University.

Crisp, James E. 2005. Sleuthing the Alamo: Davy Crockett’s Last Stand and Other Mysteries of the Texas Revolution (New Narratives in American History). Oxford University Press.

Davis, William C. 1998. Three Roads to Alamo. New York: HarperCollins World, 1998.

Davis, William C. 1999. Interview with Stephen F. Hardin, Alamo de Parris.

de la Peña, José Enrique; Carmen Perry trans. and ed. 1975. With Santa Anna in Texas: a personal narrative of the revolution. College Station: Texas A & M Univ. Press.

de la Teja, Jesús F. 2017. “Seguín, Juan Nepomuceno,” Handbook of Texas Online.

De León, Arnoldo. 1997. They called them Greasers: Anglo attitudes toward Mexicans in Texas, 1821-1900. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Durham, Robert L. 2005. “African Americans and the Fight for the Alamo,” Black History. The Second Flying Company of Alamo de Parras.

Edmondson, J. R. 2000. The Alamo Story: from early history to current conflicts. Plano, Tex: Republic of Texas Press.

Fehrenbach, T. R. 1968. Lone Star; A History of Texas and the Texans. New York: Macmillan.

Fowler, Will. 2010. Santa Anna of Mexico. Lincoln, Neb: University of Nebraska Press.

Graham, Don. 1998. Giant Country: essays on Texas. Fort Worth: TCU Press.

Gray, William Fairfax. 1997. The Diary of William Fairfax Gray: From Virginia to Texas, 1835-1837. Dallas: Southern Methodist University.

Hardin, Stephen L. 1994. Texian Iliad: a military history of the Texas Revolution, 1835-1836. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Henson, Margaret Swett. 1990. “Politics and the Treatment of the Mexican Prisoners after the Battle of San Jacinto,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, vol. 94, #2, 189-230.

Horsman, Reginald. 1981 Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Hutton, Paul Andrew. 1995. “The Alamo as Icon,” The Texas military experience: from the Texas Revolution through World War II. Joseph G. Dawson, ed. College Station: Texas A&M University.

Huffines, Alan C. 1999. The Blood of Noble Men: an Illustrated Chronology of the Alamo Siege and Battle. Austin, Tex: Eakin Press.

Jackson, Ron. 1998. “In the Alamo’s Shadow,” Black History. The Second Flying Company of Alamo de Parras.

Kelley, Michael G. 2011. “Most Desperate People: The Genesis of Texas Exceptionalism.” Dissertation, Georgia State University.

Lack, Paul D. 1985. “Slavery and the Texas Revolution,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, vol. 89, #2, p.181-202.

Lack, Paul D. 1992. The Texas Revolutionary Experience: A Political and Social History, 1835-1836. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

Lindley, Thomas Ricks. 2003. Alamo Traces: new evidence and new conclusions. Lanham, Md: Republic of Texas Press.

Long, Jeff. 1990. Duel of Eagles: the Mexican and U.S. Fight for the Alamo. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc.

Lord, Walter. 1968. “Myths and Realities of the Alamo,” The Republic of Texas. Stephen B. Oates, ed. Palo Alto, Cal: American West Publ.

Lundy, Benjamin. 1836. The War in Texas: A Review of Facts and Circumstances, Showing That This Contest Is the Result of a Long Premeditated Crusade against Government, Set on Foot by Slaveholders, Land Speculators, &c. with the View of Re-Establishing, Extending, and Perpetuating the System of Slavery and the Slave Trade in the Republic of Mexico. Philadelphia: Printed for the author, by Merrihew and Gunn, No. 7, Carters’ Alley.

Lundy, Benjamin. 1837. The War in Texas: a review of facts and circumstances, showing that this contest is a crusade against Mexico, set on foot and supported by slaveholders, land-speculators, &c. in order to re-establish, extend, and perpetuate the system of slavery and the slave trade. Philadelphia: Printed for the Publishers by Merrihew and Gunn.

Markstein, Donald D. 2010. “Texas History Movies,” Don Markstein’s Toonopedia.

Merk, Frederick, and Lois M. Merk. 1972. Slavery and the Annexation of Texas. New York: Knopf.

Nelson, George S. 1998. The Alamo: an Illustrated History. Uvalde, Tex: Aldine Press.

“New Texas History Movies.” n.d. [description of new book]. Texas State Historical Association.

Pennybacker, Anna J. 1888. A new history of Texas for schools: also for general reading and for teachers preparing themselves for examination. Tyler, Tex: Published by the author.

Ramos, Raúl A. 2008. Beyond the Alamo forging Mexican ethnicity in San Antonio, 1821-1861. Chapel Hill: Published in association with the William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies, Southern Methodist University by the University of North Carolina Press.

Reichstein, Andreas. 1989. Rise of the Lone Star. College Station: Texas A & M University Press. (German edition 1984.)

Reichstein, Andreas. 1989b. “Was there a Revolution in Texas in 1835-36?,” American Studies International, vol. 27, #2, p. 66-86.

Shuffler, R. Henderson. 1962. “The Signing of Texas’ Declaration of Independence: Myth and Record,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, vol. 65, #3, pp. 310–332.

Smithwick, Noah, and Nanna Smithwick Donaldson. 1983. The Evolution of a State; or, Recollections of old Texas days; comp. by his daughter, N.S. Donaldson. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Stenberg, Richard R. 1934. “The Texas Schemes of Jackson and Houston, 1829-1836,” The Southwestern Social Science Quarterly, vol. 15, # 3 (December), p. 229-250.

Taylor, Quintard. 1998. In search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528-1990. New York: W.W. Norton.

Torget, Andrew J. 2015. Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Tucker, Phillip Thomas. 2010. Exodus from the Alamo: the anatomy of the last stand myth. Havertown, Pa: Casemate.

Tucker, Phillip Thomas. 2017a. America’s Forgotten First War for Slavery and Genesis of the Alamo, Vol. 1. Lulu.com.

Tucker, Phillip Thomas. 2017b. America’s Forgotten First War for Slavery and Genesis of the Alamo, Vol. 2. Lulu.com.

Vázquez, Josefina Zoraida. 1986. “The Texas Question in Mexican Politics, 1836-1845,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 89, #3 (Jan.), p. 309-344.

Vázquez, Josefina Zoraida. 1997. “The Colonization and Loss of Texas: A Mexican Perspective,” in Jaime E. Rodríguez and Kathryn Vincent, eds.. Myths, Misdeeds, and Misunderstandings: the Roots of Conflict in U.S.-Mexican Relations. Wilmington: SR Books.

Walraven, Bill, and Marjorie K. Walraven. 1993. Magnificent Barbarians: little-told tales of the Texas Revolution. Austin, Tx: Eakin Press.

Weber, David J. 1988. “Scarce More than Apes: Historical Roots of Anglo-American Stereotypes of Mexicans,” Myth and History of the Hispanic Southwest: Essays. Weber, ed. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Zaboly, Gary S. 2011. An Altar for their Sons: the Alamo and the Texas Revolution in contemporary newspaper accounts. Buffalo Gap, Tex: State House Press.

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian who has curated more than 30 exhibitions. His next exhibition, Dining with Rolando Briseño: A Fifty Year Retrospective, opens August 13 at Centro de Artes in San Antonio. Cordova has previously addressed racism and the Alamo in Glasstire in 2019 in “The Alamo, Texas Independence, and Race” and in 2021 (augmented in 2023) in “Is It Time for San Antonio’s Fiesta to Secede from San Jacinto? A Modest Proposal.” “Is It Time for San Antonio’s Fiesta to Secede from San Jacinto? Part II” will be published on April 21.

8 comments

I was brought up on the Alamo story of sacrifice and heroism and would love to believe it but like the rest of the world l have become cynical when it comes to talk of hero’s… sadly.

A deep, important piece, updating the meaning of “thorough.” Thank you Ruben. And love seeing Enrique Martinez King of the Hill.

The author went to a lot of trouble to smear Texas & the legend of the Alamo. Spain was an imperialistic nation. It conquered Mexico & laid claim to much of the lands in Texas & America’s southwest, slaughtering the native Americans living in those states & stealing their lands. And when Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, it was more than happy to hang onto the Spanish conquests. So, Mexico’s claim to those lands weren’t maintained for very long & weren’t very strong. Mexico had its own African slaves. And it also enslaved many Indians living in Mexico. But Mexico was ravaged by revolution, war, civil unrest, & banditry for decades during that era, so that slavery never took root in Mexico to the extent that it did in America & South America.

So, every nation on earth has its warts. America just has fewer of them than the others.

One can always find worthy heroes, Sam. But they are rarely the ones that are manufactured to serve a dubious cause. Of the Americans who participated in this struggle (one way or another), my hero is Benjamin Lundy, the abolitionist Quaker who traveled to Mexico to attempt to establish a colony for freed Blacks. (One of the barriers to abolition in the North is that most Northerners didn’t want to live among free Blacks.) Additionally, Lundy knew exactly what would happen if the Texians prevailed: slavery would be expanded in Texas, which would be annexed as a slave state, and the South would secede from the Union, leading to enormous bloodshed. His foresight proved to be more accurate than the “history” written by generations of Southerners. On the notion of “sacrifice” at the Alamo, the death of the occupiers had little effect on the war, contrary to the myth that sacrifice at the Alamo brought victory at San Jacinto. Perhaps that is a myth I can take up in a future article.

It seems your hero was a custom to lying and hypocrisy, seeing how both he and Quincy Adam’s seem to support the idea of stealing Texas from Mexico as long as it benefited themselves. It’s a shame that we don’t instead remember someone like Amos Pollard, a true abolitionist and true hero, a rarity from the North. He wrote for abolitionist newspapers and yet also fought bravely on behalf of Texas against Santa Anna. He was also a surgeon who cared even for the wounded soldiers of the enemy. He would later die at the Alamo. Perhaps you may learn more from him than Lundy.

Thanks, Hills. I was originally only going to write a short intro to my Alamo catalogue, but found a much bigger literature than I thought existed. So I tried to be thorough, and I am glad that it was of value to you. Glad you liked the Enrique Martinez, too. He was rare artistic skills, as well as a unique vision.

Milt: You accuse me of going “to a lot of trouble to smear Texas & the legend of the Alamo.” I merely wrote a historiography, utilizing credible sources. If you regard history as a “smear,” that is only because the beliefs or legends you cherish have no basis in history. If my aim was to smear Texas, I would merely have quoted the racist declarations of its initial leaders. For a sampling, see: “Is It Time for San Antonio’s Fiesta to Secede from San Jacinto? A Modest Proposal.” https://glasstire.com/2021/06/23/is-it-time-for-san-antonios-fiesta-to-secede-from-san-jacinto-a-modest-proposal/ And I would have emphasized the horrible treatment of Mexican Americans, Native Americans, and Blacks in Texas, which in many respects was worse than elsewhere in the U.S.

Your condemnation of Spain (at the time of the conquest of Mexico) as an imperialistic nation that oppressed indigenous peoples is accurate. But you should recognize that the entire present-day U.S. was taken from Native Americans. Moreover, given the vast areas taken from Mexico, that territory represents a double conquest. Additionally, the U.S. has long been the most imperialistic nation on earth, with a shameful history of invasions, assassinations of foreign leaders, fomented coups, “regime changes,” colonial wars, proxy wars, etc. The U.S. has been on the wrong side of nearly every liberation movement, it has military bases all over the world, and it still has colonies (“territories”) where the inhabitants lack the vote and many other rights normally afforded to citizens. So the U.S. has the most “warts,” not the fewest.

You maintain that “Mexico’s claim to those lands weren’t maintained for very long & weren’t very strong.” It was a longer-standing claim than the fledgling U.S. had when it overthrew the colonial yoke of Britain. You seem to blame Mexico for the offenses committed by the Spanish. But why don’t you acknowledge that the U.S. had no credible claim to this territory whatsoever?

It is absurd to claim that “revolution, war, civil unrest, & banditry for decades” prevented slavery from taking “root in Mexico to the extent that it did in America & South America.” Compare the racial mixing that took place in Mexico (particularly after liberation from Spain) with the practices of slavery, genocide, segregation, lynching, etc. that took place in the U.S..

Dave,

You say Lundy “was a custom [sic] to lying and hypocrisy” because he wanted to steal Texas from Mexico. On the contrary, Lundy wanted to found a colony for freedmen from the U.S. within Mexico (as a part of Mexico). It was the Texians, of course, whose goal was to steal Texas from Mexico, which is what they did. As for Amos Pollard, whom you call “a true abolitionist,” why would a true abolitionist die fighting for the cause of slavery? Pollard arrived in Texas in 1834, and quickly joined the Texian (slavery) cause. It is a strange (or at least a hypocritically opportunistic) “true abolitionist” that would do that. A true abolitionist (like Lundy) would be fighting on the other side. Despite his opposition to slavery, Pollard was all too happy to join the armed struggle to take Mexican land.