Raul Servin (b. 1946), “Olvidate del Alamo #2” (Forget the Alamo #2), 2003, acrylic on canvas, 16 x 20 inches, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova, from the exhibition “The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth.” In vertiginously shifting positive and negative space, the façade of Servin’s Alamo church seems to be completed by a black United Farm Workers eagle. The red background also reads as a screen of blood, alluding to the loss of life during the Texian Revolt, the Mexican-American War, and the Civil War. In 1836, abolitionist Benjamin F. Lundy warned in a pamphlet called The War in Texas that slavery was a paramount issue in the conflict and that a successful revolt would lead to annexation by the U.S., followed by the secession of a slave republic, causing blood to “flow in torrents,” and the land to be “drenched with their [your children’s] crimson gore!”

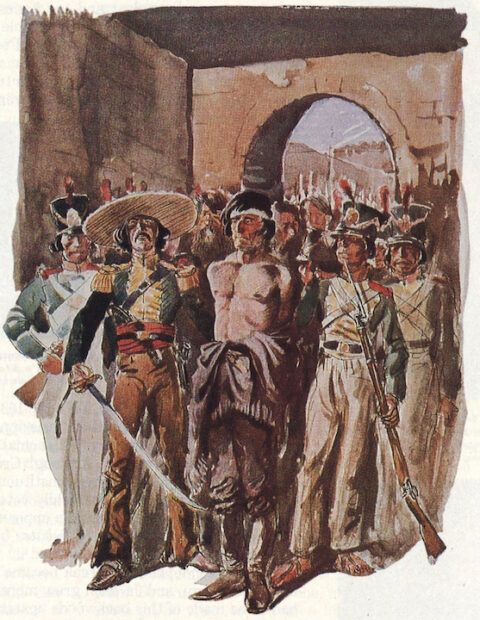

“Davy Crockett before Santa Anna,” 1934, illustration by John W. Thomason, Jr. from “The Adventures of Davy Crockett,” published by Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Mexico regarded the Texian insurrectionists as “pirates, ” so captured prisoners (including Davy Crockett), as well as the substantial number of Texian combatants that had fled the Alamo during the short battle, were summarily executed. After an even shorter battle at San Jacinto, Texian forces massacred Mexican soldiers and raped some of the Mexican women who had accompanied them.

The Texians struggled and fought to perpetuate slavery against continuous Mexican opposition to that institution. See Randolph B. Campbell, An Empire for Slavery: The Peculiar Institution in Texas, 1821-1865 (Louisiana State University Press, 1989); Randolph B. Campbell, William S. Pugsley, and Marilyn P. Duncan, The Laws of Slavery in Texas: Historical Documents and Essays (University of Texas Press, 2011); and Andrew J. Torget, Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850 (University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

After San Jacinto, the Texians abused Tejanos, including the ones who had been instrumental in preserving slavery in Texas. Slavery was a centerpiece of the Texas constitution, and the Texians continued and even intensified their genocidal policies against Native Americans after independence. Newly annexed to the U.S., Texas, in fact, would serve as a Trojan horse for the conquest of Mexico.

Samuel E. Chamberlain, “Rackensackers on the Rampage” (massacre at cave near Agua Nueva), watercolor, gouache, and pencil, San Jacinto Museum. Photo: San Jacinto Museum.

In the words of eyewitness Samuel Chamberlain, an Illinois volunteer: “The cave was full of [Arkansas] volunteers, yelling like fiends, while on the rocky floor lay over twenty Mexicans, dead and dying in pools of blood, while women and children were clinging to the knees of the murderers and shrieking for mercy… nearly thirty Mexicans lay butchered on the floor, most of them scalped. Pools of blood filled the crevices and congealed in clots” (Amy S. Greenberg, A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico, Alfred a Knopf, 2012).

Future president Ulysses S. Grant, who served as a lieutenant during the Mexican-American War, wrote of the abuses by “about all the Texans.” According to Greenberg, many of these soldiers had “thrilled to tales of Texas heroism and Alamo martyrs.” They consequently viewed Mexicans with “deep enmity” and “conflated [them] with Indians and African American slaves.” As Jeff Long puts it: “No one enjoyed the war more than Texans and Southern ‘volunteers,’ who plundered, murdered, and raped their way through Mexico” (Duel of Eagles: the Mexican and U.S. Fight for the Alamo, William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1990).

“An Available Candidate: The One Qualification for a Whig president,” 1848, political cartoon when generals Winfield Scott and Zachary Taylor, veterans of the Mexican-American War, were vying for the presidential nomination of the Whig party. Photo: Library of Congress.

Subsequently, as James E. Crisp told Smithsonian Magazine in 2004, the Alamo “became a hammer for bashing Mexican Americans in Texas.” As noted by historian David Montejano, “Remember the Alamo” became “the essence of Texas celebrations,” wherein Mexicans were viewed as “subjugated enemies,” making the prospect of “equity with Mexicans a rather absurd prospect” (Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986, University of Texas Press, 1987).

The Alamo and San Jacinto battles engendered extremely bitter feelings. Neither battle serves as a fitting source of inspiration for a celebration of San Antonio’s diverse communities and heritage, especially now that we are a quarter of the way into the 21st century. With respect to Fiesta, I recommended in Part 1 that San Antonio should keep the party, but “lose the war.”

Yet core Fiesta commemorations remain Alamo-centric, with quasi-religious, secret ceremonies held inside the Alamo church, and public rituals outside of it (see Part 1). The church also serves as a primary focal point during Fiesta parades. In fact, parades pause in front of the church, where photographers and film crews are stationed. Parade participants perform and vogue for the cameras, knowing this is essentially Fiesta’s center stage.

Direct commemorations of the battles remain part of Fiesta. On April 22, 2024, the Alamo Mission Chapter of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas is sponsoring the 106th Pilgrimage to the Alamo (note the religious terminology), “in honor of the Alamo Heroes and the heritage of Texas.” It starts at the Tobin Center Vietnam War Memorial and concludes with a wreath-laying ceremony. “Period dress” or “Fiesta attire” is recommended. Ersatz war medals are certainly welcome, but do they really mean to encourage the wearing of crazy hats?

The Alamo Heroes Chapter of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas sponsors an Annual San Jacinto Victory Celebration. Listed activities include an award given to a seventh-grade student (they certainly favor a “heroic” version of Texas history, one that Texas lawmakers mandate in the curriculum), a lecture by a military guest speaker, and a lecture by the president of Fiesta. Thus a war-centric vision remains at the heart of Fiesta.

How could Fiesta be reconceptualized? A book by Trinity sociologist Amy Stone that focuses on the LGBTQ community has important insights about festivals and inclusion and exclusion. She says large public festivals are “intended to include everyone in the city because these festivals are about cultural citizenship. Festivals are supposed to be a time when the city comes together as one to appreciate the diverse contributions of people within it.” Stone emphasizes that during these festivals, “whose culture gets included and valued, which events are allowed, and how different communities are represented, become socially significant and fraught questions.” Representation is paramount. Her book explores “what it means to have a sense of belonging in a city, [to] be valued for one’s culture, [and to] navigate city tradition….” (quoted from the abstract for Queer Carnival: Festivals and Mardi Gras in the South, NYU Press, 2022).

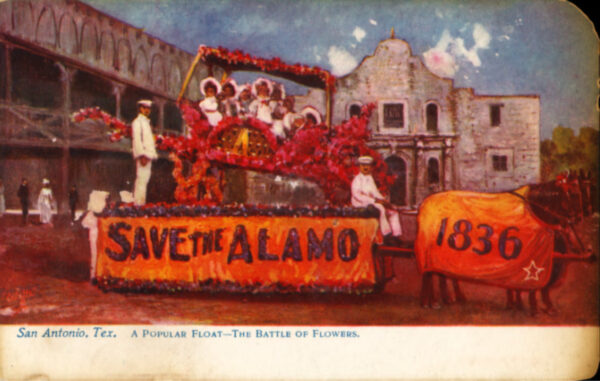

Vintage postcard, with illustration of a Battle of the Flowers parade float bearing the motto “Save the Alamo.” Photo: Wikipedia.

Fiesta San Antonio, now an eleven-day celebration, began as a Battle of Flowers parade in 1891. The successors of the power elite that created Fiesta use it to ceremonially re-enact — and thus reaffirm — their foundational power through rituals inside and outside of the Alamo church (see Part 1).

Investiture ceremony of King Antonio Clyde Johnson IV, April 22, 2023. Photo: Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, U.S. Army Photograph by Spc. Demond Dean. Hatless, wearing a red cape, King Antonio walks through a phalanx of Texas Cavaliers with drawn swords that leads to the Alamo church. He will be crowned with a military-style hat with a red plume in front of the church.

Investiture of King Antonio Bart Simpson, April 2, 2022. Photo: Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, U.S. Army Photograph by PFC Gianna Elle Sulger. Note the podium in front of the church where the ceremony took place.

Investiture of King Antonio Bart Simpson, April 2, 2022. Photo: Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, U.S. Army Photograph by PFC Gianna Elle Sulger. After the investiture ceremony, King Antonio, accompanied by San Antonio Mayor Ron Nirenberg, emerges from a phalanx of Texas Cavaliers with drawn swords.

During Fiesta, members of the two most exclusive groups — prominent businessmen and heiresses, spouses, and relatives of wealthy men from established Texas families, which might be regarded as an aristocracy of commerce and wealth — cosplay by parading as soldiers and European-style royals.

The Texas Cavaliers Investiture ceremony (pictured above), which takes place in front of the Alamo, “honors the memory of the matchless heroes who fell at the Alamo.” King Antonio is welcomed by the mayor of San Antonio and is given the key to the city.

Battle of Flowers parade. Photo: Visit San Antonio. Royalty belonging to the Order of the Alamo (and her court) have for years sported trains that are fifteen feet in length, weigh 50 pounds, and take a year (and a lot of money) to make.

Battle of Flowers parade. Photo: Visit San Antonio. Royalty belonging to the Order of the Alamo (and her court) have for years sported trains that are fifteen feet in length, weigh 50 pounds, and take a year (and a lot of money) to make.

As Stone noted for this op-ed, “In my book Queer Carnival, I address ways that events like Mardi Gras and Fiesta are a space for status intensification for cultural elites in a city.” She adds: “These festivals are the source of much merriment, but they also create opportunities for the wealthiest people in the city to enrich their social and economic ties in an exclusive way.”

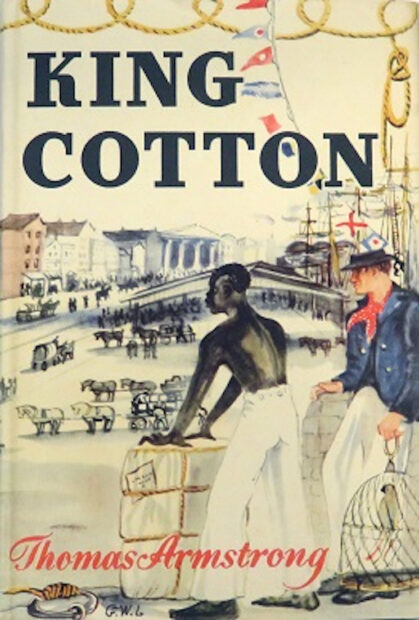

G. W. L., “King Cotton,” 1947, book cover of novel by Thomas Armstrong, published by William Collins, Sons. Photo: Wikipedia.

All the while, this elite is celebrating a false version of history. The artist Mel Casas — whose painting Humanscape 56 (San Antonio Circus) (1969) is discussed in Part 1 — observed: “Fiesta is in conjunction with the Alamo and is a fake patriotism based on a fake history” (“A Conversation with Mel Casas and Ruben C. Cordova,” in Víctor A. Sorell and Scott L. Baugh, eds., Born of Resistance: Cara a Cara Encounters with Chicana/o Visual Culture, University of Arizona Press, 2015). Also, see my “Debunking Alamo Myths” in Glasstire.

In a discussion of his processional statue called Spinning San Antonio de Valero (2009), artist Rolando Briseño notes that in place of genuine history, the Alamo narrative that is taught in Texas is a story “whose purpose is to legitimate the privileged status of Anglo Americans in a hegemonic manner.” He is hopeful that the Alamo can instead “become a place where all people can go to leave behind discord and contemplate the convergence of cultures” (Ruben C. Cordova, The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth, San Antonio: Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, 2018, p. 138-141).

Fiesta’s first king, fittingly called King Cotton, was crowned in 1896. Two elite groups, the Order of the Alamo and the Texas Cavaliers, have played a central role in Fiesta and have continued to perpetuate an Alamo mythology. See Part 1 for a discussion of these two groups, their tradition of crowning their own royals, and the role the Alamo church plays in their ceremonies.

These groups were severely criticized in the early 1970s for their lack of ethnic diversity, which resulted in substantial changes to Fiesta. The Mexican American Legal Defense Fund (MALDEF), for instance, declared in 1971: “While it is the right of any private organization to be selective in its membership, organizations which discriminate . . . should not have the direct or indirect support of public facilities and accommodations” (Tom Walker, “Hail to Thee, George E. Fischer,” Texas Monthly, April 1983).

As noted in Walker’s article, criticisms of Fiesta’s lack of diversity, such as the MALDEF statement quoted above, compelled the Fiesta Commission to invite Mexican American groups to participate in Fiesta, and to allow more organizations to crown their own kings and queens. It did not result, however, in substantial racial integration within the two most exclusive groups. The Fiesta Commission was created by the San Antonio Chamber of Commerce in 1959. In 1970, the City of San Antonio gave it additional authority to coordinate Fiesta events (see Jennifer Norris, “Fiesta’s Origin Story: What Parades and Queens have to do with Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie,” San Antonio Report, March 30, 2022).

Recommendations for Changes to Fiesta

The words “San Jacinto” were dropped from the festival’s name in 1959. In the hope of starting a conversation about Fiesta, I have listed several additional suggestions below, based on discussions with many San Antonians who want a more democratic, more inclusive, non-war-oriented citywide festival.

Community activist Rosie Castro, for instance, told me: “I very much favor re-birthing Fiesta or rebranding Fiesta and stripping it of control by any group other than a community-wide, appointed board that should be composed of a diverse group mirroring the city’s population.”

(1). Move the date of the festival away from April 21, the anniversary of the San Jacinto battle, to the first week in May, making it a battle-free spring festival.

(2). Enforce greater diversity or deny public accommodations. While Fiesta San Antonio is not technically part of the city of San Antonio, this large carnival celebration could not take place without public accommodations on public land and facilities. Moreover, the festival receives vigorous support and promotion from the city.

Consequently, the city of San Antonio should either compel the two exclusive groups named above to have greater ethnic diversity or should deny them access to the city-owned land they use during Fiesta, such as the area in front of the Alamo church, and the streets and the section of the river that are used for parades. The same goes for any direct or indirect funding or subsidies these groups may receive from the city.

(3). Remove class-based requirements for Fiesta royalty. If, as the Texas Cavaliers say now, their King Antonio is only the King of Cavaliers, then why not call that sovereign King Cavalier? Moreover, why should the El Rey Feo title go to the person who raises the most money? (See Part 1 for a history of these kings.)

Can no other kinds of value be found to make one fit to be a symbolic sovereign? Is money the only measure of worth in San Antonio? Let us bring an end to checkbook despotism! Give non-wealthy people the opportunity to parade as fake royals, if that’s their fantasy. After all, rich people can do it on their own, any time they want.

Most importantly, San Antonio should have an overall King and Queen of Fiesta as unifying symbols (instead of the largely segregated sovereigns we have now). They should be able to come from any background, even, I daresay, an artist, a musician, a poet, a social worker, an educator, a volunteer to charitable causes, a dreamer, etc. This crown should not be the sole possession of an exclusive group. Rather, the symbolic sovereigns should be chosen democratically.

(4). Reimagine and re-brand Fiesta. No exclusive groups should dominate it. A community-wide board (with rotating members) should reflect the city’s diverse population. Diversity — including diversity of occupations held by symbolic sovereigns — should be a stated goal of Fiesta.

(5). Make Fiesta more affordable, so the non-affluent have greater opportunities to participate in it. Fiesta raises millions for local charities, attracts tourists, and has a very substantial economic impact on San Antonio. But at what cost? The escalating entrance fees, the high costs of food and drink, and fees for seating at parades have squeezed out too many locals, especially families who are not economically well-off.

It would accomplish little to democratize Fiesta’s structure and organization if the growing economic barriers to participation are not addressed. Organizations seek to raise ever more money and to set records. Some kind of balance needs to be struck between money-raising and equitable access.

The Alamo, Fiesta, and White Supremacy

Luis Valderas, “The Confederate States of La Muerte (Death),” 2018, acrylic on cotton rag paper, 54 x 36 inches, collection of the artist. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova. From the exhibition “The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth.”

I reproduced a number of flaming racist statements made by leading Texians in Part 1, so I include only a couple here as a sample. Steven F. Austin, leader of the Texians, wrote to Senator L. F. Linn of Missouri on May 4, 1836, when he was not yet aware of the Texian victory at San Jacinto. In the letter, Austin declared: “A war of extermination is raging in Texas — a war of barbarism and of despotic principles, waged by the mongrel Spanish-Indian and Negro race, against civilization and the Anglo-American race….” He emphasizes that the former are “all the natural enemies of white men and civilization” (Eugene C. Barker, ed., The Austin Papers, 3 vols., University of Texas Press, 1926).

Mirabeau B. Lamar, the second president of the Republic of Texas, outlined his policy to eliminate all Native Americans in his inaugural address in 1839: “The white man and the red man cannot dwell in harmony together. Nature forbids it.” He advocated “a rigorous war… pursuing them to their hiding places without mitigation or compassion.” He would not allow reservations or attempts at coexistence. As Doug J. Swanson puts it, “the Indians were to be expelled from Texas. Or killed” (Cult of Glory: The Bold and Brutal History of the Texas Rangers, Penguin Books, 2020).

The first cotton plant that sprouted in Austin’s colony led inexorably to the Civil War. As James M. McPherson put it: “The Missouri Compromise had contained the genie of slavery expansion for a generation. Texas unstopped the bottle….” (quoted in Joel H. Silbey, Storm Over Texas: Annexation Controversy and the Road to Civil War, Oxford University Press, 2005). Texas became a slave state by dint of decades of arduous planning and effort: “The acquisition of Texas as a slave society occurred after forty years of preparation and rehearsal, and thirty of strenuous and successful colonization by planters” (Roger G. Kennedy, Cotton and Conquest: how the Plantation System acquired Texas, Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 2013).

Yet, in mainstream histories, the Alamo church is a preeminent symbol of freedom. In Texas, the Alamo is presented as the “cradle of Texas freedom.” In a 2020 op-ed in the San Antonio Report, I refer to the Alamo as “the cradle of Texas slavery, and a host of other oppressions.”

Concerted efforts were made to kill Native Americans or to drive them from the state. Survivors were marginalized. Tejanos were dispossessed of property and rights. Many Tejanos were so oppressed after the establishment of the Texas Republic — including some of the Texians’ most important and faithful allies — that they had to flee to Mexico. Blacks suffered grievously when they were enslaved. After Reconstruction, they were subject to virtual penal slavery known as “slavery by another name” (New York Times editorial board, “Documenting ‘Slavery by Another Name’ in Texas,” New York Times, August 13, 2018).

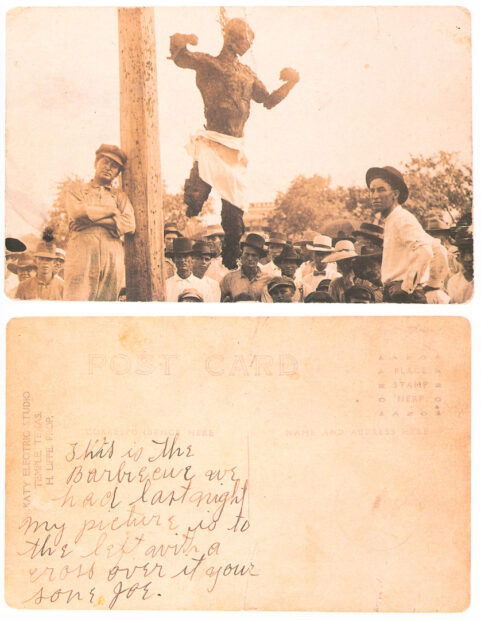

Lynching Postcard, Temple, Texas, July, 1915. Photo: Wikipedia. Also featured in the documentary short film “Lynching Postcards, ‘Token of a Great Day,’” directed by Christine Turner, 2021 (currently streaming on Paramount+). Will Stanley was lynched and burned by a crowd of about 10,000 whites in Temple, Texas in July of 1915. This barbaric act, like many other racial-terror lynchings, had a carnival atmosphere, with concessions, picnics, merriment, and grisly souvenirs. It was commemorated in a postcard image that included members of the mob. The sender of this postcard wrote on the back: “This is the barbeque we had last night My picture is to the left with the cross over it your son Joe[.]” Burning the bodies of lynched Blacks was a Texas specialty that came to be known as “lynching Texas style.” Also see James Allen, ed., “Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America” (Twin Palms, 2000).

In the work by Valderas illustrated above, the Alamo church is in the center of the Confederate flag that has skulls instead of stars. This is fitting, because Austin’s plantation colonies replicated Southern slave states.

In his “Cornerstone Speech” of 1861, Alexander H. Stephens, vice-president of the Confederate States of America, predicated racial inequality as the foundation of the Confederacy. When Texas seceded from the United States in February of 1861, one of its grievances was “the debasing doctrine of the equality of all men, irrespective of race or color.”

It should come as no surprise that slaves were actually auctioned on the Alamo grounds. Charles T. Smith, a member of the Knights of the Golden Circle (a kind of KKK predecessor group), in a unit called the Company of Alamo Guards, told the San Antonio Express in 1917 how the Alamo differed at the time of the Civil War. He noted a platform with external stairs on a second floor that “was one of the old slave markets where Negroes were put up at auction” (cited in George S. Nelson, The Alamo: an Illustrated History, Aldine Press, 1998).

This would have been the second floor of the Long Barrack (which was demolished in 1913) rather than the church itself (I incorrectly linked Smith’s quote to the church in my catalog The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth, Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, 2018). As an important step towards a more forthright and accurate history of the Alamo, I suggest that a historical plaque be placed on the Long Barrack, noting that it served as “an old slave market.”

Eric Gable, in a review of Holly Beachley Brear’s Inherit the Alamo: Myth and Ritual at an American Shrine (University of Texas Press, 1995), refers to the Alamo as “America’s premier white identity shrine” (American Ethnologist, vol. 22, No. 4, Nov. 1995). He calls her book “a wonderfully concise account of the ways that Anglo heritage organizations — the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, the Texas Cavaliers, and the Order of the Alamo — use the shrine to celebrate themselves in ways that inevitably denigrate a Hispanic Other.”

Fiesta originated as a festival by and for Anglo-American elites to celebrate whiteness. By continuing to link Fiesta to the Alamo and the San Jacinto battles, the festival maintains a direct connection to white supremacy. Historically, Alamo symbolism has resulted in disastrous — and sometimes fatal — consequences for people of color.

Marcel Salas, civil rights leader, professor, former San Antonio City Councilman, and author of The Alamo: A Cradle of Lies, Slavery, and White Supremacy (Sentia Publishing, 2021), gave me this statement about Fiesta’s connection to white supremacy:

“The original celebration of the defeat of Mexico (Fiesta) is a disgrace, as it was more of a victory party for white supremacy. The Battle of the Alamo and San Jacinto was a victory for the slave owners of Texas and white supremacy. It was all about a white supremacist celebration that has been exposed to the truth.”

Chris Tomlinson, co-author of Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth (Penguin Books, 2021) provided me with the following analysis of Fiesta and why it should be changed:

At a time when people across the country are reassessing the harmful origin myths that perpetuate discrimination in this country, it’s high time San Antonians disassociate Fiesta from the white supremacist legends underlying the Texas Revolt.

Fiesta and the Battle of Flowers Parade have a long, troubled history but remain an important city tradition. Texans don’t need to throw out our history, we need only address it honestly. The battles of the Alamo, Goliad, and San Jacinto were fought mostly by racists who traveled from the United States to steal sovereign territory from the government of Mexico. Bona fide Texans were far and few between. The insurrectionists wanted to guarantee slavery and expand the American South.

The same men who fought Santa Anna went on to fight Abraham Lincoln to perpetuate white supremacy. These men do not deserve our esteem.

Why Symbols Matter: Miss Fiesta and Texas Cavalier School Visits, c. 1966-1968

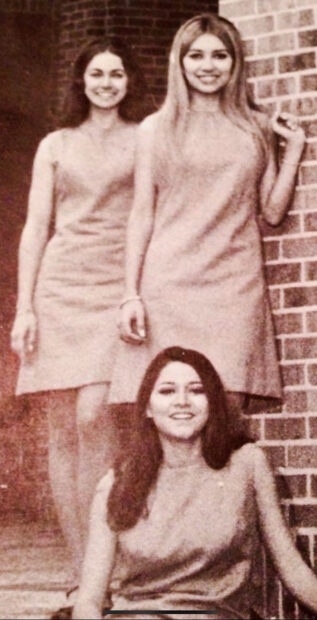

Sylvia Croley (center), with two of her Alpha Sigma Tau sorority sisters at St. Mary’s University, c. 1967. Photo: newspaper clipping courtesy of Sylvia Croley.

Sylvia Croley, a retired high school teacher, counselor, and athletic coach, was the first Latina finalist at her university in the 1967 Miss Fiesta contest. Recalling that era, she notes that if a San Antonio public school teacher caught a student speaking Spanish, the principal would give that student “three licks with a big paddle.”

The criteria for entering the Miss Fiesta competition had almost entirely excluded women of Mexican descent. Croley notes that, just a few years earlier, only students at Trinity — the most elite private university in San Antonio — had been allowed to compete in the pageant. In 1967, students from Trinity, St. Mary’s, and Our Lady of Lake (the latter two are Catholic schools) were eligible for the competition.

Young Latinas — who had only recently begun to attend college in substantial numbers — faced another barrier. Only women who belonged to sororities were eligible. At the time, says Croley, Mexicans were not admitted into mainstream, “white” sororities. She had been instrumental in forming Alpha Sigma Tau, a Latina-majority sorority at St. Mary’s. Croley applied to the Miss Fiesta competition, and a dean approved her academic credentials, which allowed her to proceed.

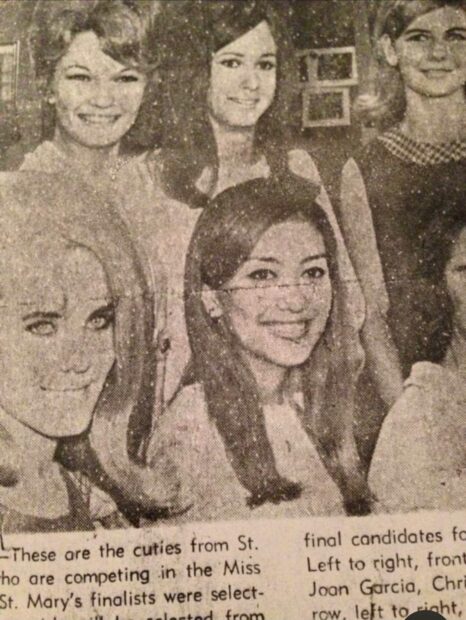

Finalists for the Miss Fiesta pageant at St. Mary’s University, 1967. Croley is in the lower center. Photo: San Antonio Light newspaper clipping, courtesy of Sylvia Croley.

Croley was one of the eight finalist competitors for the title from St. Mary’s University. She declined a home visit from the San Antonio Conservation Society because her father worked three jobs and they lived far from the affluent part of town, where the Conservation Society members lived. Croley was invited to the formal tea at which the two finalists were selected to represent St. Mary’s. But because she had declined the home visit, she was not allowed onstage to perform the model walk and to answer the question posed to each contestant. Croley recalls that the other St. Mary’s finalists for Miss Fiesta “were from prominent families — I think they were all from Alamo Heights.”

After the competition, the athletic department presented Croley with a bouquet of yellow roses, which caused her to burst into tears. “I didn’t care about winning — I just wanted to represent my heritage,” says Croley, “that was the important thing — to be there publicly, to show my blood and my culture.”

“You just never forget this experience,” adds Croley. “It’s like a big mark in my heart.” After the competition, Croley reflected on the phenomenon of Fiesta: “I wondered why the celebration was called ‘Fiesta’ — why was a Spanish word used — because the top-of-the-line people involved in it did not allow Blacks or Hispanics. The King Antonios and the Order of the Alamo royalty were all white.”

Asked for a final reflection on Fiesta, Croley replied: “I wonder if it will ever fundamentally change, with respect to the Cavaliers and the Order of the Alamo?”

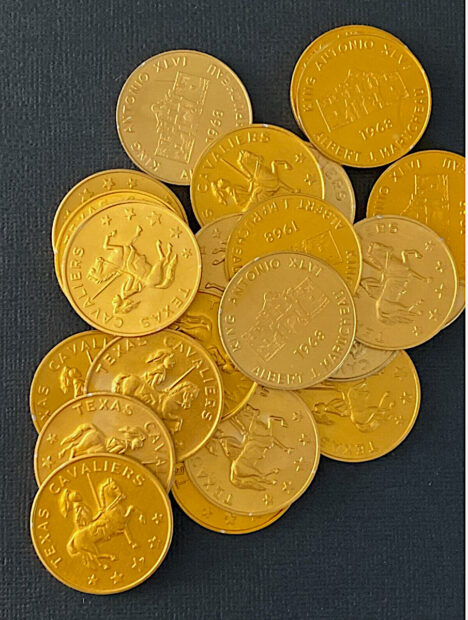

A group of Texas Cavalier King Antonio coins, facsimile reproductions of the 1968 coin. Photo: eBay.

A San Antonian I know well gave me the following account of King Antonio’s visit to his middle school, which took place circa1968. This is how he perceived King Antonio’s grand entrance:

“An entourage of big autos came to my school. King Antonio was riding in the biggest car of all — a Cadillac convertible. I thought he was a REAL king — the REAL, WHITE king of San Antonio.”

He notes how happy the children were to have this opportunity:

“It was a chance to get out of school. We were excited. The kids were screaming and thronging around the King.”

He doesn’t remember much about what the king said, other than “a few words about Fiesta,” and that he “encouraged us to go to the parade with our families.” Then, causing even more excitement and chaos, King Antonio and his entourage started handing out gold-colored coins: “All the children struggled to get a coin,” recalls my source, “They were ecstatic if they got one.”

Texas Cavaliers King Antonio coin, with King Antonio on Horseback, holding a lance, facsimile reproduction of the 1968 coin. Photo: eBay.

One side of the coin showed the King as a knight on horseback, brandishing a lance. (I think it is meant to be a lance rather than a sword.) When the Cavaliers were founded in 1926, with their membership composed of two leading business organizations, they had a jousting tournament with knights on horseback.

The Texas Cavaliers and the Order of the Alamo were the brainchild of the Virginia native John B. Carrington. He founded the Order of the Alamo in 1909 and the Texas Cavaliers in 1926. Even though he failed to turn them into state-wide organizations, Carrington is responsible for San Antonio’s “(almost entirely Anglo) royalty of bankers, lawyers, car and hardware dealers that choose a King Antonio for us” (Heywood Sanders, “Roots of Fiesta Royalties,” San Antonio Current, April 13, 2016, who discusses Laura Hernandez-Ehrisman’s book Inventing the Fiesta City, University of New Mexico Press, 2008).

My source recalls: “He was so special that he had his own coins.”

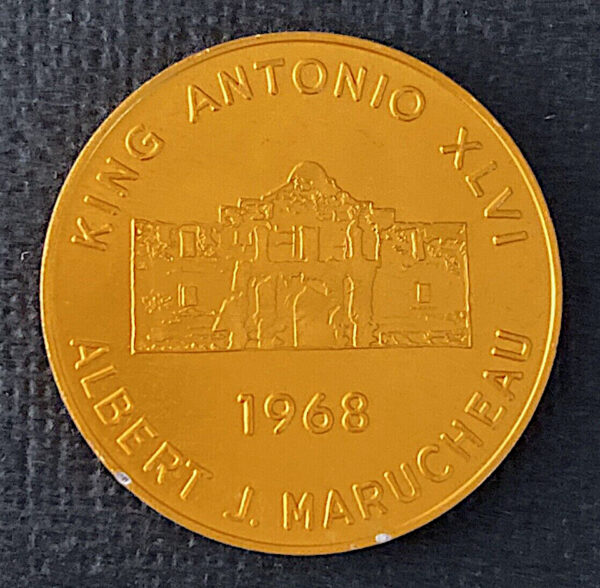

Reverse of Texas Cavaliers King Antonio coin, with an image of the Alamo church, inscribed date, name of Albert J. Marucheau, King Antonio XLVI, facsimile reproduction of 1968 coin. Photo: eBay.

An image of the Alamo was on the back of the 1968 coin (and other coins I have seen from that era), along with the king’s title, name, and the number of his reign. The latter is in Roman numerals, as if he were a Roman emperor or a regent of yore.

My source noted that most of the children suffered disappointment in their quest for a coin: “Before most of us could get our own coin, they drove the King off in a hurry.”

King Antonio had vanished, as quickly as he had appeared, which contributed to his mystique.

Reverse of Texas Cavaliers King Antonio coin, 1966, with the Alamo, the date, and Alfred G. Beckmann’s name. Photo: eBay.

The novelist, film producer, and University of Texas at San Antonio professor John Phillip Santos recalls the visits of King Antonio to Mount Sacred Heart, his Catholic grade school. His young, impressionable mind sometimes made strange connections: “When the JFK assassination was announced — I heard it at school —I thought he had been killed at Sacred Heart by the nuns!”

“King Antonio would do a promenade at Sacred Heart’s church,” says Santos, who now likens these appearances to a visit from the Spanish Viceroy during Mexico’s early colonial period.

Attendance was mandatory. Santos has particularly vivid memories of the last King Antonio visit he witnessed at Sacred Heart. He recalls King Antonio driving up in a big Lincoln Continental convertible, from which “he would toss coins for the children.” Yet young Santos sensed that “something seemed off.” With the exception of four or five of his friends, “everybody else was in awe.”

He and his close friends would throw spear grass at one another during recess. During the final royal visit Santos witnessed at Sacred Heart, which took place when he was in third grade, he and his friends decided to engage in a “spontaneous insurrection.” They had “laid up quite a bit of spear grass,” which they launched at King Antonio. Since they were far from their costumed regent, their act of symbolic resistance went unnoticed by the king and his court, as well as by school authorities. Nonetheless, for other reasons, Santos was expelled from Sacred Heart that year and told to try his fortunes in the public school system. He did well and became a Rhodes Scholar.

A former San Antonio school teacher in the Edgewood Independent School District recalled that King Antonio was barred from visiting her school:

“Our superintendent, Dr. José Cárdenas refused to let King Antonio visit the schools. I don’t remember all the details or the consequences, but it was wildly talked about as scandalous behavior for a superintendent to defy the social routines.”

José Ángel Cárdenas, who had a very distinguished career, was the first school superintendent in Bexar County who was of Mexican descent (see Handbook of Texas Online).

Cárdenas barred King Antonio in 1971. As noted in the Walker article cited above, 1971’s King Antonio, Buick dealer Charles Orsinger, received another title with a Roman numeral when he was sarcastically dubbed “Antonio Non Grata I.”

Walker also provides Cardenas’ rationale (procured in 1983) for blocking King Antonio’s visit to his school district:

“Even a play king has a relationship to his subjects. And to little minority children, this Anglo king in his fancy uniform and fancy carriage presents a negative role model. They will always perceive him as belonging to a different ethnic group from theirs. If the Cavaliers want to discriminate, fine. But let them go off in a corner and discriminate by themselves rather than sending their king to schools full of children from the ethnic groups they discriminate against. Understand, though, I have nothing against the Cavaliers as individuals.” Cárdenas smiles and adds, “Some of my best friends are Cavaliers.”

In the 1983 Texas Monthly article, Walker also quotes Joe Bernal, who was an important activist and legislator. Bernal had this to say about the Texas Cavaliers and their school visits:

… the king’s school visits are bullshit. Children are very susceptible to such things. You could dress a king up as a clown and take him into the schools and the kids would love him just as much…. I equated the Cavaliers with a militaristic quasi-KKK because we had not been able to budge them from being anti-black, anti-brown, and anti-Jew. I still do.

In 1969, Bernal was a State Senator when he played a pivotal role in ending de jure segregation in Texas. The fact that it lasted that long is one of the enduring legacies of Alamo symbolism.

In 1972, however, Bernal failed to win reelection, attributing his loss, in part, to opposition from prominent Cavaliers. As noted in Walker’s article, Bernal had blocked the appointments of two powerful Cavaliers (former King Antonio John Steen and construction magnate H. B. Zachry, Jr.) to a commission and a board. As justification, he had characterized the Cavaliers as a “discriminatory social club.”

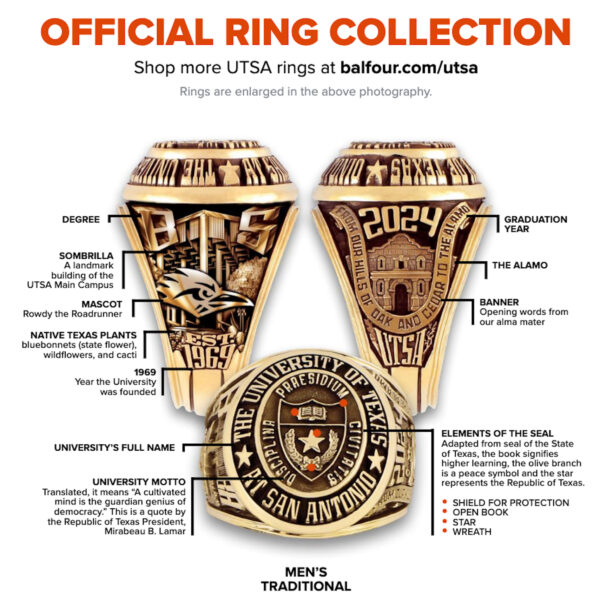

I turn my attention now to a peculiar custom involving the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA). I was astonished to learn from Kristal Orta-Puente, an artist, UTSA alumnus, and now a doctoral candidate in history at Southern Methodist University, that degree recipients are encouraged to have their rings “spend a night in the Alamo” before they receive them.

According to the UTSA Alumni Association, over 10,000 UTSA rings have reposed in darkness at the Alamo since 2012. Orta-Puente recalls that in 2019, an orange and blue van spirited the UTSA rings (including her own) from its northern campus to the Alamo shrine, where, implicitly, some magical power (or perhaps retrograde ideology) was instilled in them. That van ride transgressed the realm of the university (logic and reason) to the realm of myth, magic, and religion.

The “traditional” style UTSA class ring has the head of Rowdy the Roadrunner (the school mascot) on one side and the Alamo church on the other. The motto, “Disciplina Praesidium Civitatis,” is a summary Latin translation of a quote from Mirabeau B. Lamar: “A cultivated mind is the guardian genius of democracy.” Lamar is mentioned above as the genocidal second president of the Republic of Texas. He was one of the most ruthless, brutal, and racist men that ever made a name for himself in Texas — and that’s saying something. Can’t UTSA find a less offensive Texan from which to crib a motto? This is an issue that should concern UTSA students, alumni, faculty, Native Americans, and anyone who opposes genocide. At the same time, I am not surprised to see the Alamo image (the ultimate Texian symbol) united with one of the most dastardly Texian leaders.

Indoctrination in public education takes many forms in Texas, from grade school visits by King Antonio, to “heroic” history lessons in seventh grade (with highly censored textbooks), to a public university that casts a spell on its rings by sending them on a formal pilgrimage, where they are ceremonially immersed in the Alamo during a nocturnal sojourn. UTSA doesn’t explicitly say exactly what this one-night stand is supposed to accomplish, but the graven Alamo image on the ring presumably partakes of and absorbs the numinous qualities that inhere within the shrine. Somehow enriched and irradiated, like a core of plutonium, the rings can then be bestowed on the new graduates.

Cornyation: Satire as a Form of Resistance to Exclusion

A Fiesta Medal-laden Master of Ceremonies is making such an obsequious low bow that he lies on the ground, Cornyation, 2012. Photo: Lauryn Ferris.

Perhaps the most piercing and trenchant criticisms of Fiesta’s royal pretensions are to be found at Cornyation, which was born in 1951 when King Anchovy crowned the Empress of the Cracked Salad Bowl. Amy Stone, author of Cornyation: San Antonio’s Outrageous Fiesta Tradition (Trinity Press, 2017), characterized its origins for this article: “it began as a playful satire on the debutante traditions of the Coronation of the Queen of the Order of the Alamo, and the first script was written by a gay man who also participated in the Coronation.” (Also see Part 1.)

Satire, burlesque, and outright mockery form a potent three-way attack on Fiesta conventions. See Bryan Rindfuss’ well-illustrated article and interview with Stone in the San Antonio Current, which has pictures of Elaine Honigblum as the Vice-Empress of Vice (1959),

1. M. Jeanie Pancakes as Queen of the Leather Scene (1982), and Cari Hill as Vice-Empress of the Court of Outrageous Pretentiousness (1991). The latter rides a hobbyhorse emblazoned by a Texas flag, in front of a man in a football uniform that is a parody of King Antonio. For a slideshow of vintage Cornyation pictures, click here.

As Stone notes: “Cornyation scripts in the 1950s and 1960s often criticized elitism and exclusivity in the city, and the event was eventually kicked out of the Night in Old San Antonio for being too bawdy and critical.”

The Fiesta Medal Tradition

For the past 30 years, Fiesta medals (military-style medals hanging from ribbons) have been an important part of the festival. In 2015, Jack Morgan charted “The Weird History Behind Fiesta Medals” for TPR. He traced the medal’s origins to an officer stationed in San Antonio.

Morgan interviewed cultural anthropologist Michaele Haynes, who connected publicly distributed Fiesta medals to the coins (like the ones pictured above) first minted by the Texas Cavaliers in 1946. When Fiesta royals initially wore medals, they did not distribute them to the general public. “Up until recently,” says Haynes, “you did not get one of the special medals from the Queen of the Order of the Alamo unless you knew her.”

Haynes notes that in 1961, Joske’s department store created a cardboard framework (with a removable center) to hold the Texas Cavalier coin, along with a hole through which a ribbon could be strung. The Cavalier coin was thus transformed into a virtual medal. Haynes notes that after 1971, a few Fiesta groups began making their own Fiesta medals.

The key development took place in 1980, when, as noted by Haynes, Lt. Col. Childers, who was then stationed at Ft. Sam, was responsible for the first military-style Fiesta medal that had a large distribution. Fiesta medals, however, did not become a widespread phenomenon until the 1990s.

Now anyone can make a medal (for nonprofit purposes), for any queen or non-royal. Morgan spoke with Larry Algueseva, who dubbed his dog “the Fiesta Canine Queen,” and who had been creating medals in the image of his dog queen for a decade.

Anywhere Anytime Plumbing’s Fiesta Medal, with the motto “Don’t believe the hype, Don’t flush the wipes,” 2019. Photo: eBay.

Corporations such as Walmart and Whataburger routinely issue Fiesta medals, but my favorite corporate medal is the plumbing medal pictured above, with a shimmering commode fit for Donald Trump, as well as helpful preventative advice.

A satiric faux corporate medal appeared in 2019 when Los Pollos Marijuanos (a satirical take on Los Pollos Hermanos from the Breaking Bad television series) issued a medal with the motto “legalize it.”

Esperanza Peace and Justice Center Fiesta Medal, with the motto “Fiesta is Racist,” 2015. Photo: Facebook.

Perhaps the most controversial Fiesta medal was the one issued by the Esperanza Peace and Justice Center in 2015, which declared “Fiesta is Racist,” for reasons of exclusion and the falsifications of history that are treated in this op-ed.

Kristal Orta-Puente’s Journey

Kristal Orta-Puente, “The 18-Pounder,” 2012, photograph. This cannon is a replica of a famous cannon used at the Alamo, which was a Swedish-made 9-pounder that was bored out to shoot an 18 pound ball.

I’d like to conclude by examining Orta-Puente’s complex and changing views of the Alamo and of Fiesta. She made what she calls a “journey from Alamo lover to Alamo critic,” inspired in large part by her experience of majoring in Mexican American Studies at UTSA.

Orta-Puente’s mother worked in the book section of the Alamo gift shop for over 20 years. As a teenager, Orta-Puente spent a great deal of time at the Alamo, where she imbibed and deeply cherished “the myths about the ‘defenders of the Alamo.’” In time, she became very interested in the story of the preservationist Adina de Zavala (who wanted to save the complete Long Barrack). Orta-Puente identified with “her passion to save something so special to Texas.”

When Orta-Puente began her photographic career, she met with the leadership of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT), who administered the Alamo at that time. They loved her work, and Orta-Puente was contracted as a vendor to sell her photographs on consignment. Her best seller (illustrated above) was of a large cannon, with the Alamo church in the background.

Orta-Puente’s “eyes were opened” in 2017 when she was at UTSA, after her mother retired, and after she quit selling photos at the Alamo. Her educational epiphany was not limited to her classroom experiences:

I had been exposed to folks in the community, artists in particular, who felt Fiesta was racist, which is why they boycotted it. They and others told me that the Alamo was a white supremacist symbol. It got me thinking. And as I dove deeper into the activist community, these voices were even louder. So then, when I started to read the books and learn the history behind the myth, I felt cheated. I felt lied to. I was angry. I even asked my mom if she knew this stuff, and she said she did, but that she would not speak badly about a place that provided her with a secure job to provide for our family. It was hard for her to be disloyal to the job, and she had to make hard choices. I don’t blame her, I get it. It is part of why I felt I needed to accept all those dualities. Two things can be true and they can contradict. You can love something and hate it too.

Orta-Puente’s disenchantment with the Alamo was paralleled by her disenchantment with Fiesta, though her reservations about the latter had been generated over a longer time span. Fiesta had been so important to her family that her father took a week off of work in order to celebrate it. Orta-Puente recalls:

I used to love Fiesta. I grew up with my parents going every year to the night parade and NIOSA [Night in Old San Antonio]. Those are some of my favorite memories. But the more you see a lot of white faces on one side, and brown on the other, you start to wonder what it is all about as you grow up. You begin to question: why were they throwing flowers in the Battle of the Flowers parade? I didn’t understand what that was all about — that it was a replacement for war — war against the “evil” Mexicans. Why is there a King Antonio and a Rey Feo? Why is he feo (ugly)?

Since 1947, Rey Feo (Ugly King) has been the king sponsored by the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), the largest and oldest Latino organization in the U.S. The Rey Feo parade was not integrated into Fiesta until 1980. The relative status of King Antonio and Rey Feo within Fiesta is a problematic issue for many people. Part 1 treats the history of Rey Feo and his eventual inclusion in Fiesta.

Orta-Puente increasingly became aware of the sharp racial and class fault lines that defined Fiesta, where disparities are not only boldly highlighted, but literally put on parade. The more she recognized these disparities, the less she enjoyed participating in Fiesta.

Kristal Orta-Puente’s class ring, UTSA class of 2019, which spent the night at the Alamo. Photo: Kristal Orta-Puente.

Orta-Puente’s appreciation of contradiction was a factor in deciding to have her UTSA class ring do a one-night stand at the Alamo:

That is why I chose for my ring to spend the night in the shine. So I never forget the lies told to us, and the drive that greed and pride can have. And to never forget to push to talk about the ugly parts as loud as we talk about the beautiful parts of our story. As a newly minted historian, I am concerned with facing all the parts of Texas I love and hate. Texas exceptionalism — the belief that Texas is the best, bigger and better than every other state, and that we’re always the good guys — is a hell of a drug, and I don’t think rehab for the state of Texas is on the table.

Orta-Puente bought a men’s ring with a diamond because it was the largest and the most expensive ring. She wanted it to be dramatic so that people would ask about it, and so that she could share her story, and encourage others to pursue higher education. She also thought it was an appropriate gesture, given her history with the Alamo. Orta-Puente did not think the night at the Alamo would imbue her ring with any special power, “other than the power I decided to give it.” In her case, she wanted it to be “a constant reminder of what I want to change about history, and I will do that by working in the community.”

She wants to acknowledge and examine myth, not suppress it, in order to make a more complete history:

Folks fighting for a revision of Alamo history are not asking for an erasure of the myth as we know it, but rather an acknowledgment that there IS a myth, and that myth has served a privileged group. We now need to find a more intelligent way to tell a complete history. The Native, ethnic Mexican, and Black communities want equitable representation of all the folks that make up the story of San Antonio, and beyond that, of Texas history. That history is complex. It is painful. But aren’t we emotionally intelligent enough to deal with it yet?

Orta-Puente would like Fiesta to be separated from the battles for which it was created to commemorate: “Yes, I would love for Fiesta to detach itself from San Jacinto. Let’s party, and let’s celebrate diversity, support non-profits, and promote art and education.”

At the same time, she would not want this detachment to come at the cost of forgetting history:

But what I would not want to happen is for us to get so far away from the events that we stop remembering where they came from at all. We have to remember and we have to talk about the real reasons Texas wanted independence in the first place and that is unequivocally because they wanted Mexican land, and to keep slavery legal in Texas. So, for myself, I will continue to work through the pain, the lies, and the complexity of having difficult conversations about how we tell our history. I am committed to trying to make a difference.

Laura Varela, photograph documenting Enlight-Tents, a public art installation by Vaago Weiland and Laura Varela at the Alamo for Luminaria Arts Night in San Antonio, Texas, March 14, 2009. From the exhibition “The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth.”

Varela projected a film with indigenous and mestizo faces on the Alamo façade as an act of resistance. These faces were multiple reminders of indigenous perseverance. After this performance, Varela was told that projections would never again be allowed on the Alamo façade.

Meanwhile, scales are rapidly falling from the eyes of Texans. The more columnist Chris Tomlinson researched Texas history, the more he came to doubt the standard narrative. He told his friends Bryan Burrough and Jason Stanford about the high volume of hate mail he was receiving for “Texas needs a rebranding away from racially charged myths,” in his April 10, 2019 column in the Houston Chronicle. Then he declared: “Everything you think you know about the Alamo is a lie!”

Rising to the challenge posed by this assertion, the three friends researched and wrote the book Forget the Alamo, published in 2021. When Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick canceled a discussion with two of the authors that was scheduled at the Bullock Texas State History Museum in 2021, Forget the Alamo became a bestseller. It has caused many a scale to fall from the eyes of readers.

There is heightened recognition that the heroic narratives about freedom-loving Texians casting off the yoke of Mexican despotism are false histories based on Texian propaganda. The Texians were enslavers, who, in league with the Southern U.S. slaveocracy and with land speculators, wanted to seize Mexican land, particularly East Texas, whose rich soil was ideal for growing cotton. The slavocracy also wanted to prevent Mexico (bordering on Louisiana) from serving as a sanctuary for escaped slaves. The Texians had little use for Mexicans or Native Americans, whom they deemed unworthy to possess the lands they inhabited. Blacks, in their view, were fit only for slavery. The freedoms they coveted were not to be extended to other peoples.

The myths of the Alamo die hard, and they have tainted Fiesta, which, from its inception, has been allied with racism, exclusion, and disparity. Although Fiesta has been democratized in multiple respects in the last half-century, more changes are warranted. It is time to free Fiesta from San Jacinto and the Alamo, to let it stand on its own as a festival that brings all of San Antonio’s people together, instead of celebrating false narratives and battles whose function is to set people apart.

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian who has curated more than 30 exhibitions. His next exhibition, Dining with Rolando Briseño: A Fifty Year Retrospective, opens September 5 at Centro de Artes in San Antonio. Cordova has previously addressed racism and the Alamo in Glasstire in 2019 in “The Alamo, Texas Independence, and Race,” in 2021 (augmented in 2023) in “Is It Time for San Antonio’s Fiesta to Secede from San Jacinto? A Modest Proposal,” and in 2024 in “Debunking Alamo Myths.” These works are based on research conducted for his exhibition catalog, The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth (Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, 2018), which was funded by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

1 comment

Excellent background and history. Eye-opening. Thank you.