Photographs are a defense to the fear of forgetting.

–Únies González

Even this show’s title, Leave the Kitchen Light On, triggers memories, while also acting as an evocative metaphor: a light in the dark, illuminating a comforting domestic space, showing the way home. A return. A signal. A message. An invitation.

Únies González started as a poet in high school in Houston, writing while taking photographs. With the encouragement of their sister, Danielle, and their teachers at the University of Houston, they moved further into photography. Their remarkable installation at Stinson House, in a modest Houston bungalow, is a multi-sensory, multi-level experience that is almost too overwhelming to appreciate in one visit. It is a shrine to family, to love in modern times, to memory, place, and identity. It is an ode to the past, in tension with the present.

Candid snapshots taken with their Instax, the Fujifilm version of the Polaroid instant camera, are found in unexpected places, in the way that memories can surface during routine domestic activities: an image of an intimate moment between folded towels in the cloud-filled linen closet; drifting, reflecting on oneself while soaking in the tub or looking in the mirror; a thought occurring while looking up at the attic door. (The thought then falling away — like a photo that Únies pointed out was actually becoming unstuck, as they were standing in the hallway under the attic door.)

But there are more objects besides the photos. Their grandmother’s worn armchair sits in the front room, their late father’s comforter covers the bed. Pulling out a dresser drawer reveals intimate moments among the underwear. And in the bedroom closet, a small TV plays home movies of friends and family, filmed mostly by Únies with their JVC Camcorder.

In the small living room another tiny, portable TV plays tapes of Little Bear, an animated television series from the 1990s, which taught “about friendship, love, and rainy days,” according to Únies. In their poetry, Únies addresses depression as a character named “Daisy,” a personification that began when they were a teenager.

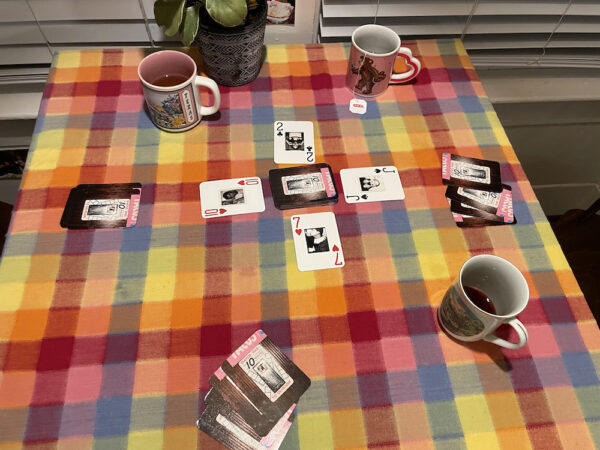

Family photos explode out of antique boxes, spreading like a whirlwind up and across the corner walls. Playing cards featuring color photo booth snaps of Únies and their boyfriend are arranged like a game that is still in process on the kitchen table. Tossed into the kitchen trash is a wedding dress.

For the crowded opening, a small living room couch, table, and rug were set up on the front lawn under an eerie light, like a haunting memory — or a safe place — in the dark. On the front porch, a young man dressed in pajamas and a robe, hired to play a welcoming father figure, sat in a rocker, smoking an empty pipe. Handwritten signs on the door urged visitors to take off their shoes, wipe their feet, be respectful, and follow the rules.

Inside, a hand-drawn map and instructions are displayed on the front room wall. Volunteer docents, followers of Únies’ Instagram page, helped explain the project to the largely young crowd. Small stickers by Lisa Frank, a children’s product illustrator from the 1980s and 90s, indicate where a visitor is meant to open shelves and drawers. There are even photos under tables, in the dishwasher, and in the sink and toilet, a kind of “I Spy game of memories,” says Únies.

The Importance of Piles

And everywhere there are piles of bright orange tangerines, or even a solitary tangerine. The citrus scent mingles with the perfume of votive candles, spread throughout the rooms of this shrine. The repetition is like a chant, but instead of repeating sounds, it’s a repeating visual object. The tangerines are obviously mementoes, and/or even an offering. Únies explains that their mother used to pack tangerines in their childhood lunch box, and that together with their boyfriend they share tangerines as a satisfying snack. Únies associates the fruit with love and with their mother, who happens to have bright orange-red hair and who was actively involved in helping Únies select and install elements of the show.

Mixing with the aromas are the sounds of Leonard Cohen on a record player. In the small office, a narrow closet is set up as a memorial to Unies’ beloved grandfather. There is a tape that plays his favorite music. Lining the closet floor are bright orange marigolds, a flower used since ancient times to honor and remember the dead, and piles of Chiclets, a candy-coated chewing gum whose name derives from the Nahuatl word for “sticky things.” Young Únies, then named Megan (they changed it, recently, to a family name), used to go with Papa, as he was called, to eat at a popular Mexican restaurant on Fairview. He would hand Únies Chiclets when he paid at the cashier.

Next to the closet is a desk covered with crumpled pieces of paper inscribed with handwritten poems by Únies. More poems litter the floor. Piles of 35 mm film swarm like nightmarish black snakes in the corner. A photo of Únies’ mother and father driving on Westheimer, taken from the back seat, hangs on the wall.

Photo of the artist’s parents driving on Westheimer, as part of Únies González’s “Leave the Kitchen Light On”

A Collaborative Effort

The installation is obviously a collaborative effort, accomplished with the participation and encouragement of family and friends. Únies’ mother, for instance, pinned the rising whirlwind of family photos to the corner walls in the living room. She also insisted on displaying rows of cartoon-covered Welch’s jelly jars that Únies used to drink out of as a child. The glass jars are lined up on shelves in one of the kitchen cabinets that visitors are meant to open. The glass display also seems like a kind of shrine. The neon-colored cartoons of childhood are a repeating theme, echoed in the surreal semi-figurative and graffiti-like paintings by Únies’ boyfriend, Dillon Barnes (whose artist name is Leche), hanging on the walls.

Friends offered advice and labor. And the installation is a labor of love, conceived and constructed out of love, a sort of temple, and a stage filled with charged objects. The candid photos, appearing in the midst of routine activities like folding a towel, make real the process of remembering, of reflecting, perhaps on connections and missed connections. Leave the Kitchen Light On is an unusual multimedia experience: poetic, thought-provoking, and moving.

Únies González’s Leave the Kitchen Light On is on view at Stinson House (2718 Ruth Street, Houston) through March 16. There will be a closing reception from 4-8 p.m. The show is on view by appointment: 713-805-9377

1 comment

A very enlightening description of the house as exhibition space. Bravo. Thank you