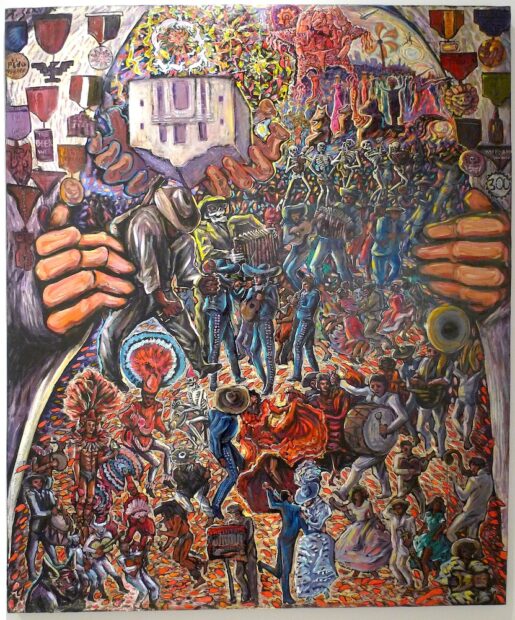

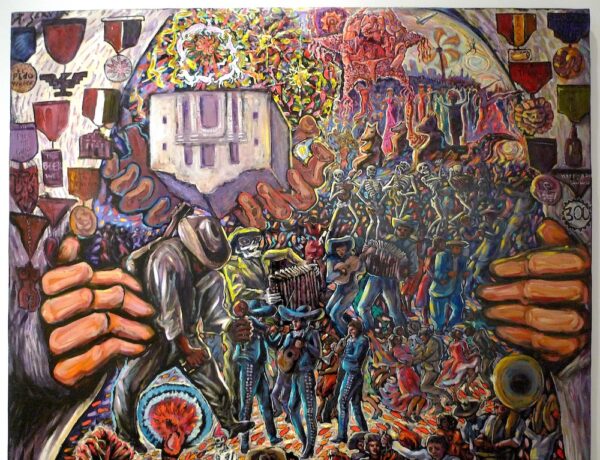

Raul Servin (b. 1946), The Music of Fiesta, 1999 with additions in 2018, acrylic and mixed media on masonite, 72 x 60 inches, collection of the artist. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova, from the exhibition “The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth,” Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, San Antonio, 2018.

I propose that the San Antonio celebration known as Fiesta be decoupled from commemorations of the battles of the Alamo and of San Jacinto. On April 21, 1836, Texian forces defeated and massacred the Mexican army and captured Mexican general and president Antonio López de Santa Anna. Fiesta celebrates this battle with lengthy festivities in April. The Covid pandemic forced the cancellation of Fiesta in 2020. It also resulted in a reduced schedule for 2021 — including the elimination of signal events, such as the coronation of the Queen of the Order of the Alamo — and the displacement of the festival from April to June 17-27. (See: “Reduced by half, Fiesta 2021’s slate of events still offers plenty for revelers to enjoy,” San Antonio Report.) That’s a good start. But it is time for Fiesta to secede from San Jacinto. My modest proposal: keep the party, lose the war.

The defeat of Mexico is celebrated annually in San Antonio on a massive scale, often with Mariachi music, Mexican costumes, Mexican food and beer, and tequila-fueled margaritas. The oldest event now associated with Fiesta, the Battle of Flowers Parade, which began in 1891, was likely inspired by a parade in Mexico City at which competing groups threw flowers at one another. One might reasonably conclude that this entire victory celebration is upside down — not just the Alamo church building in Raul Servin’s painting.

During Fiesta, the most exalted cabals of the Anglo American power elite — which have largely excluded people of Mexican descent and other people of color — convene private rituals in the Alamo church, where they choose their royalty.

The character of this royalty is perhaps best conveyed by the official description of the queen’s subsequent public coronation:

An evening of beauty and fantasy awaits those who attend the Coronation of the Queen of The Order of the Alamo, one of the central features of Fiesta San Antonio. With a spectacularly set stage, the symphony orchestra performs the accompaniment as visiting and in-town Duchesses make their full-court bows, followed by the presentation of Her Royal Highness the Princess, and the Coronation of Her Gracious Majesty, the Queen. All wear elaborate dresses and trains spangled with glittering beads, crystals, and jewels. After the court is seated within the magnificent stage setting, musicians and other[s] entertain the royalty and the audience.

Founded by San Antonio businessmen and community leaders in 1909, The Order of the Alamo celebrates Texas’ heroic struggle for independence from Mexico. The group chose its first Queen that year and staged her coronation at the Old Beethoven Halle. Thought by many to be one of the most magnificent and unusual events of its kind in the country, the Coronation of the Queen is an unforgettable evening for the whole family.

I agree that in this day and age, and in this country, this coronation is most unusual. Joe Salek, then director of the San Antonio Little Theater, witnessed the 1950 Coronation. He found it so unforgettable that he couldn’t stop laughing, so he initiated a parody called Cornyation in 1951. A wardrobe failure in 1964 caused Cornyation’s cancellation, but it was revived permanently in 1982 — for a time at a brilliantly named gay club called the Bonham Exchange. It, too, is cancelled this year.

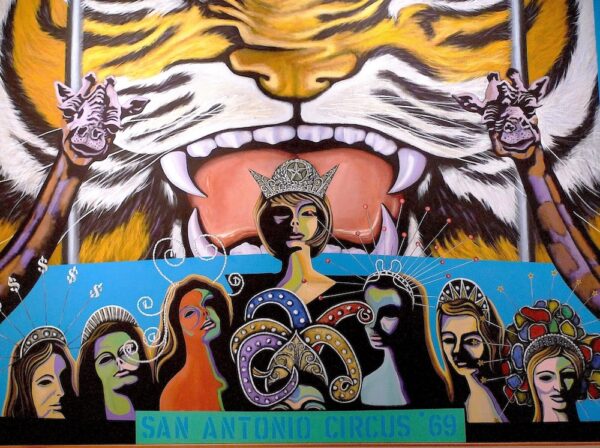

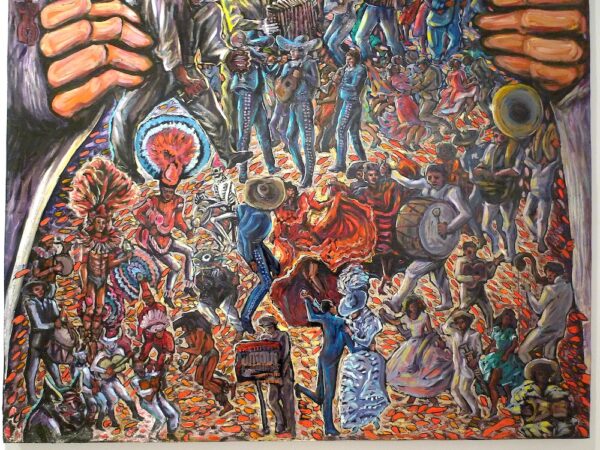

Mel Casas (1929-2014), Humanscape #58 (San Antonio Circus), slightly cropped at top and sides, 1969, acrylic on canvas, 72” x 96,” collection of the Mel Casas Family Trust. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova, from the exhibition “Getting the Big Picture: Mel Casas and the politics of the 1960s and 1970s,” Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, 2015.

Fiesta queens were also mocked in 1969 in a large painting by the estimable Mel Casas, who implied that during Fiesta, the circus was always in town. Born and raised in El Paso, Casas regarded San Antonio as a very “colonized” city. As I have come to understand more about Fiesta and its traditions, I have gained a deeper understanding of what he meant. Casas, when he was named Artist of the Year by the San Antonio Art League for 1968, famously gave a talk in which he stripped the clothes off of a blond Barbie Doll and lectured about white privilege. His prize was unceremoniously stripped away three days later. I wish I had pictures — not only of Mel and his denuded doll — but also of what must have been a very dumbfounded audience of blue-haired matrons. For a discussion of the Barbie Doll in the context of Casas’ analysis of race, sexuality, and representation, see my article “The Cinematic Genesis of the Mel Casas Humanscape, 1965 – 1967,” Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies, Fall 2011.

Similarly, Casas strips away the ersatz royals — queens, princesses, duchesses, and whatever you might call them — in Humanscape #58 (San Antonio Circus). His eight vacant queens lack eyes — their sockets are filled only by elements that project from the adjacent queen’s ridiculous tiaras: some crystal baubles, a cherry, a star. They can “see” only through — and by means of — the very regalia that confers royal status. From dollar signs on the left to stars on the right, these tiaras symbolize wealth and celebrity.

Jan Jarboe Russell reported in Texas Monthly in 1994 that Texas bloodlines and bank accounts determined who became queen, not beauty or talent. Consequently, most of the queens came from about a dozen “primarily German and English families,” who sported increasingly ostentatious and unwieldy gowns. Russell quotes one clueless queen who seemingly regarded her coronation as a birthright: “‘I don’t see what the big deal is,’ said one former queen, gaily. ‘I loved being queen. My grandmother was queen. My mother was queen. All my cousins have been in the court. To me, it’s just fun and tradition.’” The queens and their gowns through 2014 can be seen here.

Casas’ queens are flat, unreal, lacking in fundamental substance. They are rendered in patches of color that fail to flesh them out as three-dimensional personages. They are but a masquerade of royalty. Casas gives us a social pyramid of queens, with Her Gracious Majesty, the Queen rising above a subordinate — perhaps Her Royal Highness the Princess — whose tiara resembles a fool’s cap.

The two giraffes mug for the spectators of this painting with their humorously long necks, making a mockery of the human subjects that live only to be seen. Yet, by comparison, the animals are more complete and more psychologically complex than the depicted humans.

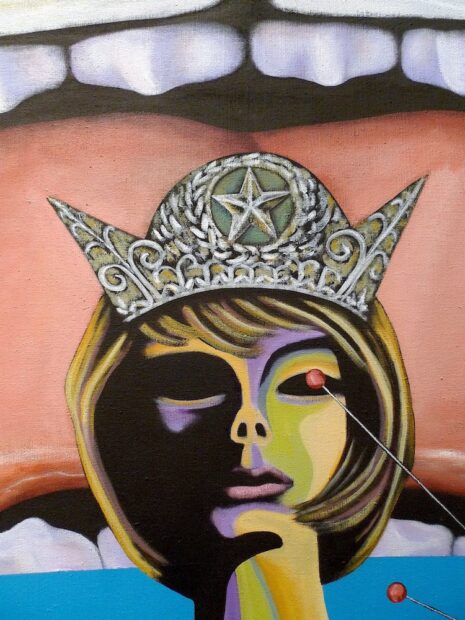

Mel Casas (1929-2014), Humanscape #58 (San Antonio Circus), detail of Her Gracious Majesty, the Queen.

Her Gracious Majesty — like the giraffes — has a long neck. She is particularly ghoulish, even in this vulgar company. The red “eye” confers a demonic quality, which reinforces the reading that the twin peaks on her Lone Star crown are indeed horns. She, in particular, could be on the brink of being devoured by the tiger. In a chapter on Casas’ political paintings, I suggested:

Perhaps the tiger, which is behind bars, represents the righteous anger of the excluded people of color, who have been dispossessed of their land and property, stripped of their culture, enslaved, forced onto reservations, incarcerated, denied the full rights of citizenship, and compelled to live in segregated cities [Scott L. Baugh and Víctor Sorell eds., Born of Resistance: Cara a Cara Encounters with Chicana/o Visual Culture, 2015].

The Order of the Alamo’s charter provided for the queen and her court, and also specified a mission to “educate its members and the public generally in the history of the Independence of Texas and perpetuating the memory of the Battle of San Jacinto.” Education, in this context, is the promulgation of the Heroic Texas narrative. It conveniently excludes the enslavement of Blacks as well as Native American removal/genocide. It enshrines Mexicans as the villains of Texas history, and the Alamo myth has always served to obfuscate and disguise the conquest of northern Mexico by the U.S. I’ll have to save the details for a future article, “Why Texas History is so Bad, and Why Texas Wants to Keep it that Way,” but for the time being, see my Glasstire essay “The Alamo, Texas Independence, and Race.”

The Texian victors frequently referred to themselves as Anglo-Celts and claimed cultural as well as racial superiority over Mexicans, whom they referred to as “greasers,” “half-breeds,” and worse. Here are a few tidbits from a vast smorgasbord of racism, from my catalogue The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth (2018):

‘The New Orleans Bee’ printed a letter in 1834 by a Texian who described Mexicans as: “degraded and vile; the unfortunate race of Spaniard, Indian and African, is so blended that the worst qualities of each predominate.” A leader of the Texian rebellion against Mexico referred to Mexicans in 1836 as “the adulterate and degenerate brood of the once high-spirited Castilian.” … Two weeks after … San Jacinto, Steven F. Austin invoked racial pollution and natural law in his letter to Senator L. F. Linn of Missouri on May 4, 1836: “A war of extermination is raging in Texas — a war of barbarism and of despotic principles, waged by the mongrel Spanish-Indian and Negro race, against civilization and the Anglo-American race… Indians, Mexicans, and renegades, all mixed together, and all the natural enemies of white men and civilization.” David G. Burnet, president of the interim revolutionary government, cited the “utter dissimilarity” between the “Anglo Americans” and “a mongrel race of degenerate Spaniards and Indians more depraved than they” as a cause of the Texas revolt. The “insuperable aversion” to mixing with “the Mexicans, a mongrel breed of negroes, Indians and Spaniards of the baser sort” was retrospectively deemed a prime cause of the war. Senator Robert J. Walker of Mississippi, who favored the annexation of Texas in 1844, dismissed most Mexicans as “mixed races… composed of every poisonous compound of blood and color.” Senator James Buchanan, who would soon negotiate the peace treaty as secretary of state, declared on February 14, 1845: “The Anglo-Saxon blood could never be subdued by anything that claimed Mexican origin.”

Given this outpouring of racist contempt, why should anyone be celebrating the Texian victory over Mexico with Mexican foodstuffs and culture?

Having appropriated a Texas-sized chunk of Mexico, the Texians and their descendents also apparently annexed her cuisine, music, and festive traditions. I’m all for keeping the fiesta; just drop the bizarre pretext for it. It is problematic for highly segregated elite groups to crown Anglo American kings and queens who preside over brown subjects. For an analysis of Fiesta, and especially of its comparatively segregated traditions, I recommend Laura Hernandez-Ehrisman’s Inventing the Fiesta City: Heritage and Carnival in San Antonio (2016). In her beautifully written book Inherit the Alamo: Myth and Ritual at an American Shrine (1995), Holly B. Brear terms the Alamo church an “empty tomb” and “the stone womb of Texas society.” In this privileged vessel, the Order of the Alamo and the Texas Cavaliers select their royals (the latter group chooses a King Antonio from its own membership). In this manner, explains Hernandez-Ehrisman, “the Alamo becomes symbolically intertwined with the maintenance and social reproduction of San Antonio’s heritage class.” Jack Morgan discusses Fiesta with San Antonians of Mexican descent (“Why Some San Antonians are Conflicted About Citywide Celebration,” Texas Public Radio, April 30, 2018). One of them, Lilliana Saldaña, a professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio, argues that Fiesta, with its fake royals, serves to “celebrate white supremacy.”

I made the sardonic suggestion in my Alamo catalogue that one would think that the Anglo-Celts might want to celebrate their victory with their own traditional delicacies. If they cannot accept full integration and real history instead of myths that justify their own power, I say let the Anglo American elite go their own way, with their own traditional foods: haggis (sheep liver, lung, and heart cooked in stomach lining), neeps and tatties (turnips and potatoes), porridge, black (blood) pudding, watercress sandwiches, boiled cabbage, Bubble and Squeak (fried leftovers, often potato or cabbage), Stargazy Pie (fish pie with the heads sticking out the crust), Toad in the Hole (sausages in Yorkshire Pudding), finished off with Spotted Dick (sponge cake) and Devils on Horseback (prunes wrapped in bacon).

Furthermore, they can extol, eulogize, and acclaim San Jacinto and the Alamo by blowing their bagpipes, strumming their banjoes, Riverdancing on the Riverwalk, and parading around in their tartan kilts.

The rest of us can move Fiesta into May, making it a battle-free, pure party celebrated at all of the missions. Alcoholic revelry is not, in any case, the best classroom for history lessons of any sort. Taking my parting line from Wayne and Garth from Wayne’s World, I say: “Party on, San Antonio, but leave the fake history and racism behind!”

Update: April 17, 2023:

The article to which this addendum is attached focused on the female Fiesta royalty chosen by The Order of the Alamo. This addendum examines ethnic diversity (or the lack thereof) within the Texas Cavaliers, another exclusive organization with a major role in San Antonio’s annual Fiesta celebrations. The Cavaliers were founded in 1926, when they began the practice of crowning one of their own members as King Antonio, supplanting earlier Fiesta kingship traditions (Mrs. Willard E. Simpson, “Fiesta San Antonio,” 1976, updated April 15, 2022, Handbook of Texas Online).

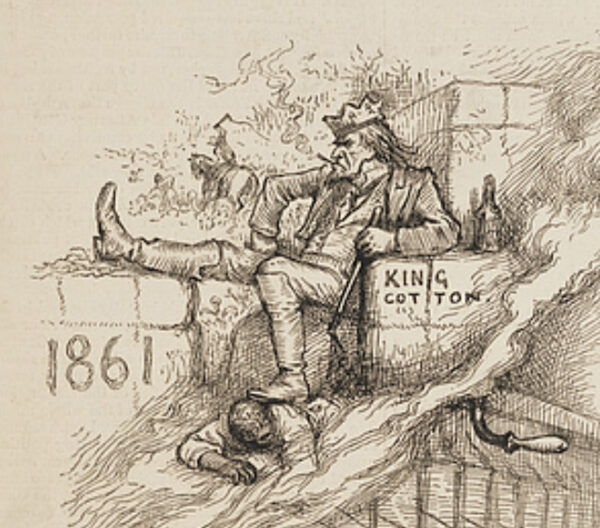

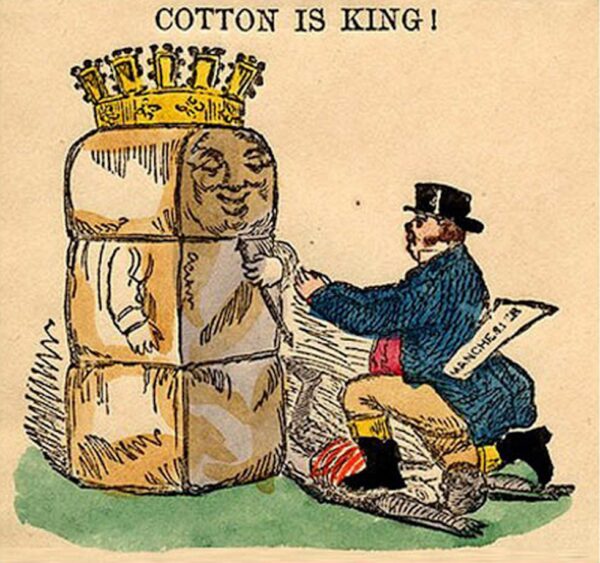

Thomas Nast “The Queen of Industry, or The New South” (detail of upper left section showing the plantation economy of the pre-Civil War South), 1882, wood engraving, illustration in Harper’s Weekly, January 14, 1882. Photograph: Library of Congress. For complete image, go here.

The first Fiesta king in 1896 was called King Cotton. This choice of name summons up the kind of plantation fantasies that were common among White elites in the old South, and, I argue below, are related to the royalist fantasies that are continuously enacted by the well-heeled cosplayers who created and continue to control important elements of Fiesta, San Antonio’s premiere public festival. After King Cotton, subsequent Fiesta kings had no names, or short-lived ones, until 1915, when the title King Antonio was born (Tom Walker, “Hail to Thee, George E. Fischer,” Texas Monthly, April, 1983).

In 1972, a reader asked the San Antonio Express-News why there had never been a Mexican American King Antonio, in a city made up of 52% Mexican Americans (“Action/Express,” San Antonio Express-News, Sunday, April 30, 1972, p. 2A). The question was taken up by the paper’s Action Express columnist, who spoke with James Gorman, Jr., Commander of the Texas Cavaliers. The columnist made this statement: “King Antonio is king of the Cavaliers, not of Fiesta.” This begs the question of why his highness is not called King Cavalier instead of King Antonio. Moreover, the Cavalier’s own “History of King Antonio” currently states that its first king “was elected by his peers to pay tribute to Alamo heroes, attend the first King’s Ball, and preside over city-wide Fiesta activities.” If he is presiding over Fiesta on a city-wide basis with the title that originated before the group existed, then he seems like something more than a mere King of Cavaliers.

The Action Express columnist notes that the group had around 350 members in 1972, none of which were Mexican American or Black. He adds that Frank Chapa had been “very prominent” in the early years of the group, “when the Cavaliers took over the duties of selecting King Antonio.” According to the Handbook of Texas Online and a UTSA Librares blog, Chapa was a founding member of the Cavaliers. Chapa had a distinguished career in the military, and his mother was descended from early San Antonio settlers from the Canary Islands.

The Action Express columnist adds that there are no racial or ethnic restrictions in the group’s charter, and he quotes one member who claimed that fathers nominate their sons, but “they are never elected.” Yet in the Cavalier’s list of “Former Kings,” one can see a repetition of family names. The Cavalier’s current “History of King Antonio” spells out this consanguinity: “Men from many of San Antonio’s most prominent families have served as King Antonio, some following in the royal footsteps of their fathers or uncles – in one case, even a grandfather!” As Walker pointed out in his Texas Monthly article in 1983: “new Cavaliers tend to be related by either blood or marriage to current and past Cavaliers…. An outsider, a nobody, can marry a woman whose father is a Cavalier and become one himself.” Thus many sons of Cavaliers do enter the group, because having a family connection is the primary mechanism for admission.

Investiture of King Antonio, April 2, 2022. Photograph: Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, U.S. Army photo by PFC Gianna Elle Sulger.

The Action Express columnist noted in 1972 that there had been “minority” nominees in recent years, but none had been elected. Of course, in San Antonio at this date, people of color constituted a sizeable majority of the population. But since the historical message of Fiesta (endlessly promulgated by the Cavaliers and the Order of the Alamo) is to glorify the Anglo invaders of Texas, there was little room for people of color in this narrative. Mexicans, of course, were akin to regicides, since they were the slayers of Davy Crockett and the other “heroes” and “martyrs” of the Alamo. Racism raged during the revolt, and it grew even stronger in the early days of the Texas Republic (see quotes in the article to which this addendum is attached). Even the “heroic” Tejanos who had assisted the Texians in preserving slavery during Mexican rule, and who had fought alongside them during the revolt, rightfully feared for their lives (some fled to Mexico). Ever since the Texian revolt, Mexicans have been the villains of mainstream Texas histories.

The Texians (and the land speculators and the forces of the slavocracy in the U.S. that financed and supported them) wanted permanent possession of Mexican land; concomitantly, they felt they needed enslaved Black people to work that land for their benefit. With respect to Native Americans, the Texians, and most of the powerful figures in the Republic of Texas, were firmly on the genocidal maniac side of the spectrum (Sam Houston was an exception). Extreme efforts were made to kill or expel all Native Americans. These factors help to account for the virtual — or total — absence of people of color within the ranks of the Cavaliers during much of the group’s existence. In the glorious Alamo/San Jacinto narrative formulated after the revolt, people of color were characterized as demons or sub-humans, fit for subservience, enslavement, death, or expulsion from Texas.

The Action Express columnist reported in 1972 that a concerned Cavalier suggested to him that Mexican American organizations could crown their own kings, who could have functions similar to those of King Antonio. “The more kings, the merrier,” he related. These suggestions represented entrenched positions made after the Cavaliers had come under fire in 1971 for their complete lack of ethnic diversity. Now that they were besieged, these Alamo fanatics appeared to want to maintain a segregated fortress mentality.

Just before Fiesta in 1971, the largely Mexican American Edgewood School District declared King Antonio non grata. State Senator Joe Bernal of San Antonio also blocked two very eminent Cavaliers (one had been king in 1967; the other was construction magnate H. B. Zachry, Jr.) from choice committee appointments, due to their active membership in a “discriminatory social club.” (Zachry likely played a large role in Bernal’s electoral defeat the next year.) The League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) Council Two, the GI Forum, and the Mexican American Legal Defense Fund (MALDEF) openly called the Cavaliers racists. To provide cover, the Fiesta Commission officially relegated King Antonio and the Order of the Alamo’s queen to the status of unofficial sovereigns. Additionally, Mexican American groups were invited to participate in Fiesta (see Walker’s discussion in Texas Monthly for more information on the material in this paragraph).

Instead of racial integration within his own organization, the concerned Cavalier in 1972 was espousing separate and unequal sovereignties. King Antonio already had a long reign as king of Fiesta. The Cavaliers utilized the Alamo church to identify with the largely Anglo settlers and mercenaries who, with some Tejanos, had attacked Mexican forces and eventually occupied the former mission. Would the Cavaliers countenance a king from the ranks of LULAC, MALDEF, or the American G. I. Forum with the title of King Antonio? And would these latter-day carnival kings have equal access to the Alamo grounds? What if they wanted to make an antithetical argument about the history of Texas? Suppose they wanted to expose the so-called “Texas Revolution” as a war fought to seize Mexican land and to preserve slavery in the face of Mexico’s repeated attempts to abolish it? Moreover, how could organizations founded as remedies for the denial of civil rights in a deeply racist state compete on equal footing with one made up of the city’s “most prominent” (and sometimes wealthiest) families?

At what Walker calls “the peak of the controversy” in 1972, the Cavaliers nominated Dr. Aureliano A. Urrutia, whose family came from Xochimilco, Mexico. Urrutia was admitted the next year, though he was not a very active participant in the group. (One wonders whether he felt as if he were a token, and if he wanted his male relatives to be Cavaliers.) This at least proved that the Cavaliers could in fact be moved — if not very far.

But the Texas Cavaliers still had no Black members, and King Antonio George E. Fischer told Walker in 1983 that given the nominations of so many relatives every year, it would be difficult for a Black to gain admission to the group, much less to become King Antonio. I am not aware of any Black or Native American members of the Cavaliers during the group’s entire history.

Walker also mentions a Mexican American judge who desperately wanted to be a Cavalier, but he had no relatives or close friends in the group to nominate him. As a “concession,” the Cavaliers instead allowed a LULAC boat in their River Parade, commencing in 1975. The River Parade was their signature event, which began in 1941. It, too, was inspired by a Mexican experience, when Cavaliers saw the decorated boats in the “floating gardens” of Xochimilco, on the outskirts of Mexico City.

By not integrating their ranks for so long, the Cavaliers denied people of color the opportunity to make important social and business contacts, since most Cavaliers were active in the business community. This exclusion also denied them the ability to vote and to serve as the city’s symbolic king. As Walker declared in his Texas Monthly article: “in the bowers of old San Antonio’s moneyed families… to be King Antonio is the supreme social honor that a man can achieve, one that he and his posterity can forever look back on with button-popping pride.” In the presence of King Antonio, Walker says, school children would gaze with “wonder…. At nursing homes the elderly would strain to touch the hem of his cape…. jets would zoom overhead in his honor as the band played ‘Off We Go Into the Wild Blue Yonder.’”

LULAC, meanwhile, had a Rey Feo since 1947, a parodic king created in opposition to the all-White Cavalier’s King Antonio (Elaine Ayala, “Ayala: Now that Fiesta is over, let’s talk about its shameful anti-Mexican roots,” San Antonio Express-News, April 6, 2022, updated April 11, 2022). Instead of merely parading around the Alamo (and other locales) as the sovereign of the city, Rey Feo raised scholarship money for needy school children. (The Cavaliers followed suit in 1989 by founding a charitable fund for children.) In 1980, the Paseo del Rey Feo (Ugly King Parade) integrated LULAC’s king into Fiesta. Walker rightfully credits Logan Stewart, the dazzlingly dressed, two-term Rey Feo (1979 and 1980) of radio station KTSA fame for this development.

But this farcical Feo king has generally been viewed as lesser than King Antonio, even though, unlike King Antonio, Rey Feo at least has a crown-shaped crown. He and his retinue also adopted military-style uniforms bedecked with medals. Nonetheless, Rey Feo is more akin to the Renaissance Lords and Monarchs of Misrule, who presided over fools during holiday seasons, such as Carnival and Christmas.

Historically, under LULAC’s watch, neither all Rey Feos nor all of the beneficiaries of its scholarship fund had been Latinx. The Rey Feo trademark is currently under dispute (Patrick Danner, “A San Antonio LULAC Council, Rey Feo Scholarship Foundation battle over Fiesta royalty trademarks,” San Antonio Express-News, November 7, 2022).

Though some had prognosticated that such a day would never come, including a good number of Mexican Americans, the Texas Cavaliers eventually did crown a King Antonio of Hispanic ancestry in 2017. And they are literally crowned (but with a plumed hat instead of a crown) right in front of the Alamo church. Its 95th king was Dr. Michael A. Casillas (see “Former Kings”). For a short film of his investiture, see “Texas Cavaliers Name First Latino King Antonio,” Spectrum News, April 23, 2017.

Cultural reporter Elaine Ayala quickly got wind of his historic election (the results were meant to be secret until his investiture) and declared: “The faux monarch will take the lead with San Antonio’s other pretend royals dressed in goofy get-ups and giant plumes” (“Finally, the Cavaliers elect a Mexican-American King Antonio,” San Antonio Express-News, June 26, 2016).

Ayala also recognized the symbolic importance of his election. She cites Anthropologist Michaele Haynes, author of Dressing Up Debutantes: Pageantry and Glitz in Texas (Bloomsbury Academic, 1998), who said Fiesta is “a window” into society. Haynes’ book description notes: “the themes of Coronation pageants represent the mythologized ethnic and class history which reinforces the hierarchical positioning of its participants.”

Casillas’ election was big news, even outside of San Antonio, and Houston Style Magazine ran a notice about his election (“Cavaliers Elect a Mexican-American King Antonio,” July 1, 2016).

At the time of Casillas’ investiture, Texas Cavalier spokesperson Arthur Cavazos gave a statement to Spectrum News that seems to stake-out three different positions in three sentences: “this is the first time that there has been King Antonio that has a Hispanic surname, and it’s a milestone. I mean, the Cavaliers have always been inclusive. They’ve grown to reflect the population of the city that they serve” (“Texas Cavaliers Name First Latino King Antonio,” Spectrum News, April 23, 2017). It’s a “first,” a “milestone,” but they’ve “always been inclusive,” yet they’ve “grown to reflect” changing demographics. This is having it all three ways.

First Latino King Antonio

I noticed that Cavazos and Casillas both avoided the M word. Neither claimed Mexican ancestry for Casillas. When Michael Quintanilla queried: “What is your Fiesta pedigree?,” Casillas replied:

First generation royalty but proud to claim many of the original Canary Island settlers as part of my ancestry. My roots go back to the founding of San Antonio in 1718. Canary Islander ancestors helped form the first municipal government in San Antonio in 1731 and my ancestors fought for Texas Independence at the Battle of Mission Conception and at the Storming of Bexar [the latter refers to the Texian attack on San Antonio, which they held for less than three months, before Mexican President and General Santa Anna took it back] (“King Antonio XCV Michael Casillas,” Express News, April 10, 2017).

For another one of my capsule histories of Texas (in addition to the Glasstire op-ed cited in the article above), see “Remember the Alamo for what it really represents,” San Antonio Report, March 5, 2020.

Note that Cavazos emphasized Casillas’ “Hispanic surname” rather than the specifics of his ancestry. I wish Quintanilla had asked Casillas whether his Hispanic ancestry was limited to Canary Islander ancestry, and whether it was all in the distant past. Casillas told Quintanilla that he had become a member of the Cavaliers thirteen years prior, and that he believed he would “not be the last Hispanic to hold this honor.”

Ayala noted in her 2016 article that two of Casillas’ brothers are members of the Cavaliers, and, of the 606 members, an estimated 10% are Latino (in a city that is 60% Latino). She added that Cavazos was admitted to the Cavaliers in 1994, when four of the sixteen new members were Latino. Ayala says “the Cavaliers have consistently added new Hispanic members annually only for about 20 years.”

Today, Henry B. Gonzalez, III, grandson of the congressman from San Antonio who served 37 years, is the Properties and Alamo Officer of the Cavaliers, as well as a member of its board of directors (see “Meet the King’s Men”).

Why Has Faux Royalty Survived in San Antonio?

What accounts for the survival of the racially exclusive clubs (the Cavaliers and the Order of the Alamo) in San Antonio that control important parts of Fiesta? In his Texas Monthly article, Walker points out that in the dynamic cities of the New South, corporations have been agents of change. San Antonio city fathers courted military bases rather than corporations (which they feared would bring unions and other undesirable changes to the city). So there were no entities that could effectively oppose segregation and favor merit over contacts.

Walker argues: “San Antonio likes a club, any club; it loves a crown, any crown; and it is quick, even eager, to bow, to curtsy, to bend the knee.” He asks what makes San Antonio “fertile turf for fake feudalism” and he gives the wrong answer. Walker places the blame on San Antonio’s multicultural heritage, a yearning “for the royalty it has had” in its Spanish colonial days. His explanation misses the mark, because empowered Anglo Americans are the ones who created the ersatz courts and brought to life their fantasies of a knightly order of brave men (not long after horses had gone out of style). It is they who have appropriated and recolonized Spanish colonial monuments. In the process, they have fetishized the Alamo church in particular.

But Southerners in general and Texans in particular did not cosplay the Spanish Empire. They had a different script, one derived from Sir Walter Scott’s romance/historical novels. Southerners suffered from what Mark Twain called “Sir Walter Scott Disease.” This was the source of their faux aristocracies, and, in Twain’s estimation, a contributing factor in the South’s downfall. William B. Travis was addicted to Scott’s novels. They filled him with false bravado. He was a terrible soldier who knew nothing about actual warfare, which is why he got all his men killed at the Alamo. But some of his letters are admired, even outside of Texas.

The conquest of Texas led to the conquest of Mexico, and the Alamo became the central symbol of both conflicts. Texas — and the remainder of the Northern half of Mexico — was taken by the sword. The Cavaliers, sword in hand, were founded to memorialize this conquest, which, perversely, through the myth of the Alamo, is presented first as righteous defense, and secondly as righteous vengeance against Mexican “tyranny.” Paradoxically, the successors of these ostensibly “freedom-loving” fighters felt that their memory was best served by a mythology of invented royal and quasi-royal courts. This is not very free and democratic, in my opinion.

Such noble fantasies dream away the harsh realities of slavery, including the fact that slave auctions were held on the Alamo grounds after the Texian/U.S. victories. Texas became a slave Republic, then a slave state, and then a member of the Confederacy. Of all the Fiesta kings, was King Cotton the only one who cared to remember these basic facts? At long last, the triumph of the North in the Civil War brought an end to slavery in Texas. Fiesta’s royal pageantry generates historical amnesia about the causes and the realities of the Texian revolt, at the same time that its in-crowd clings to myths of Alamo martyrdom. In official histories, the Alamo is posited as “the cradle of Texas liberty.” In my op-ed cited above, I refer to it as “the cradle of Texas slavery, and a host of other oppressions.”

Fiesta was founded upon a core of racist lies, which it continues to perpetuate. It is an affront to San Antonio’s history, rather than a celebration of it. Fiesta’s signature events should not be under the control of exclusive clubs that are not accountable to the public.

San Antonio’s premiere festival should be moved to another date and transformed into an inclusive celebration of the city’s history and cultures, one that adequately reflects and includes its vibrant and diverse communities.

Why am I objecting to a party? Because people of color should not be expected to continue to dance to the tune of their own subjugation.

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator. This op-ed grew out of texts in his catalogue The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth (Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, 2018). This Alamo exhibition and “American History Does Not Begin with the White Man: Indigenous Themes in the Work of Mel Casas” (Bihl Haus, 2018) were the two exhibitions he curated for San Antonio’s tricentennial.

16 comments

About time. I went to my 1st fiesta in 1980 or 1981 and was baffled by the purpose of the month-long party.

Thanks, Roberto. I pretty much ignored it until my research for the Alamo exhibition. The contradictions are astonishing.

I always said let Queens and King have their parade in the streets of 09’nors , and celebrate their own white supremacy with their peers of wealth. Digo yo !

Yes, Henry, and let us have our Fiesta on some other date.

I recall going to Fiesta parade and explaining to my kids and grandkids, each year, the racism in the membership of the Cavaliers, the Queen and her Court, the administrators of the Parade, the real untold story of the Alamo….

Good for you, Velma. I hope knowledge will lead to change. These foundational rituals have continued virtually unchanged for too long.

Gracias Rubén for your timely insights into the ironies of celebrating the battles that created a new slave-friendly state. I’ve been a resident of San Antonio since 1971 and have never been a big fan of the Fiestas, though I once did attend NIOSA (noisa, as I used to call it) to sample exotic eats, especially, snoot that I am, the escagot…. I’m originally from Laredo, where the locals line the streets on el veintidos de Febrero to celebrate George Washington’s birthday and watch designated prominent members of the community playing George and Martha Washington parade by to cheers from the throng. At least they are not royalty though to that effect, but are ironically as likely to be played by Mexican Americans as Anglo. What’s with this royalty thing anyway….it seems to be going into uneasy extinction, if you are aware of the angst of the British royal family coping with a dissident heir to the throne removing himself from contention.

You are welcome, Cesar. Thank you for your insights. Fake royalty might just outlive real royalty. Then it will be even more nostalgic.

Thanks for an interesting, important article. As a transplant I feel really contested about Fiesta. I am glad that the conversation is coming more to the front. “Keep the party; lose the war” is a great way to think about it.

THANK YOU! Art Speaks Truth.

You are welcome, Rick. Casas demonstrated many times in his Humanscape series that it is possible to say a great deal with a single painting.

You are welcome, Allison. I hope the dialogue continues. I have received a great deal of positive feedback on this article by people who think it is an important issue.

Excellent Job Ruben!

Thanks, Joe. I’m glad this article is still getting traction. When I learned Axios was linking it in an article on Fiesta, I decided to do an update on the Texas Cavaliers.

All of this is so true, but I wonder if the average San Antonio person really pays much attention to the Cavaliers or the duchesses any more except for the over-the top bling; so much of the festival has been co-opted by other groups in the city in recent years–when I came here in 1974 as an outsider, it all seemed so self-involved and bizarre (and can anybody outside of this in-group really sit through a coronation ceremony (I tried once–yawn). The cornyiation is back, but that’s another in-group; I think that the best of fiesta has now become local self-celebrations within San Antonio’s diverse population–so gradually, probably too gradually, it’s morphing into a real urban festival (this year it seems to be mostly about who can snare the most medals from anyone who cares to make them. By the was, the first “Queen” who ever made a public appearance in a San Antonio parade was Clara MacPherson, queen of Juneteenth in 1898!

Congratulations, Ruben, a brilliant essay.