The Amon Carter Museum of American Art may be best known both for its Charles M. Russell and Frederic Remington paintings of the American West and its extensive photography collection. However, it also has deep holdings of prints and other works on paper. Due to the light sensitive nature of these works, there are limitations on how long they can be on view and how long they must “rest” — be in dark storage — before they can be exhibited again. A few years ago, the Carter began a more intentional practice of exhibiting works on paper from its permanent collection and rotating them regularly throughout the year. With this in mind, when I visit, I’m often walking through the collection searching for new works that have just come on view.

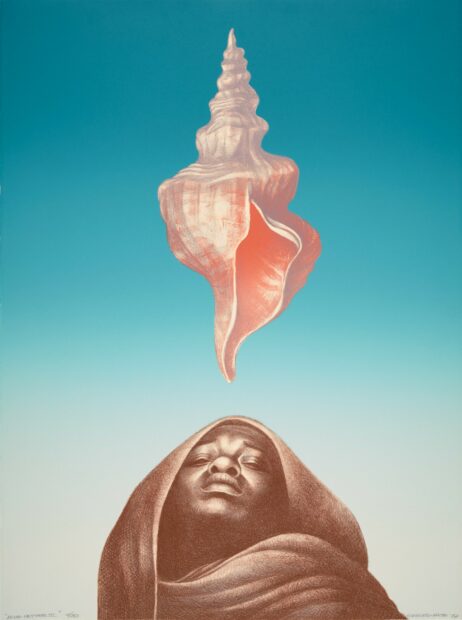

During a recent visit, I was excited to spot three color lithographs by Charles White in the museum’s Mezzanine gallery. The first to draw me in was Love Letter III, which is centered between the other two works. The seamless gradation of its background from vibrant blue to white is reminiscent of a deep blue Texas sky, and sets a strong contrast for the conch shell and figure in the foreground. The shell floats, standing straight up, in the top half of the artwork, and is rendered in shades of pink, muted lilac, and white. The bottom of the shell points down at a figure shrouded in fabric. Though we can only see from her shoulders up, the figure appears sacred as she lifts her face to the sky, her cloak draping over the top of her head and across her shoulders. In her expression there’s a hint of religious transcendence — on first glance, this could easily be a reinterpretation of Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa.

Charles White, “Love Letter III,” 1977, Color lithograph, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, TX, Purchase with funds provided by the Cynthia Brants Trust, 2020.11

White’s work is known for celebrating the dignity and beauty of Black people as well as highlighting historic and longstanding injustices like the struggle for representation in the press and in politics, wrongful convictions and legal discrimination, and violence committed against Black communities. His Love Letters series is a tribute to Black women. Though the figure in Love Letter III is anonymous, the other two works depict Angela Davis and Fannie Lou Hamer.

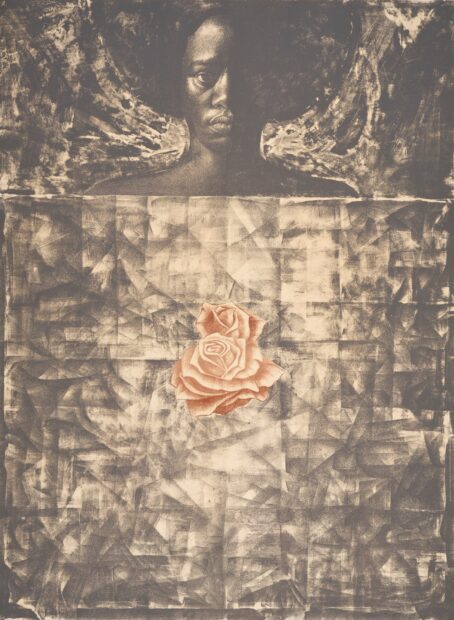

Charles White, “Love Letter I,” 1971, Color lithograph, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, TX, Purchase with funds provided by the Cynthia Brants Trust, 2020.9

Love Letter I was created in 1971 as a response to the arrest of Angela Davis. Davis, a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles at the time, was the registered owner of guns used during an armed invasion of a California courthouse. This print, unlike Love Letter III, is almost completely rendered in black and white and is filled with chaotic strokes. In the upper third of the composition, Angela Davis is depicted from the shoulders up looking solemnly straight ahead. The left side of her face is obscured by shadow, and curved markings fill the space around her. A large square shape covers the lower two-thirds of the work, giving the appearance that Davis is standing behind a sheet. This shape is also filled with markings, but these are angular, resembling folds and wrinkles. The lower section of the print is also lighter than the background surrounding the bust of Davis in the work’s upper portion. At the center of the print are two light pink roses, one fully in bloom, the other still budding. Davis is strong, resolute and simultaneously shielded by what feels like a thin barrier; the soft and fragile roses remind the viewer of Davis’ fragility. This work was used as the cover of a pamphlet for The National United Committee to Free Angela Davis and All Political Prisoners, and was also included on postcards calling for Davis’ release. The cards were printed with the following message:

Dear Governor Reagan:

Because we love Justice and Freedom;

Because we truly believe that she is being denied the presumption of innocence and equal protection under the law, as guaranteed by the Constitution of these United States;

Because we are alarmed by the effect this pre-trial, punitive imprisonment is having on her health and well-being,

We ask you, as Governor, to intercede for the release of Angela Davis on reasonable bail.

Sincerely,

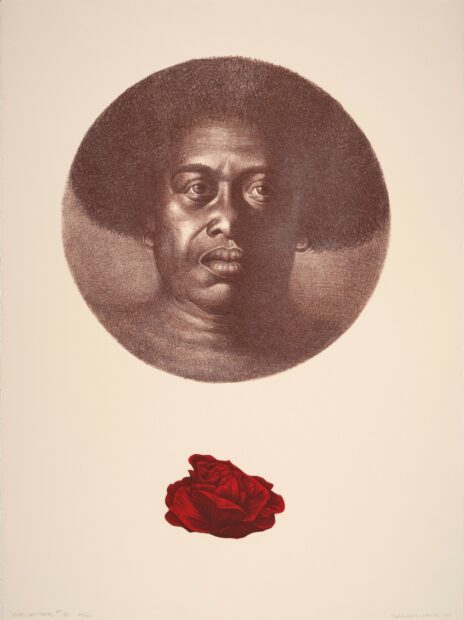

Charles White, “Love Letter II,” 1977, Color lithograph, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, TX, Purchase with funds provided by the Cynthia Brants Trust, 2020.10

Love Letter II is the simplest composition of the three works. Fannie Lou Hamer’s face is framed in a circle on an unprinted background. Hamer, like Davis, is stoic and unwavering. She faces forward with her eyes slightly lifted up. The left side of her face is partially in shadow, but both eyes are clearly visible. Below her is a deep red rose, in bloom. The image feels like a memorial. In 1961, while in surgery to remove a uterine tumor, a white doctor performed a hysterectomy on Hamer without her consent. Forced sterilization of Black women was common at the time as it was seen as a way to reduce the Black population. This experience catapulted Hamer into a lifetime of activism, and she became a leading voice in the civil rights movement. This print was created in 1977, shortly after Hamer died.

Through detailed, carefully crosshatched renderings, White illustrates the strength and perseverance of Black women. Juxtaposing the figures with symbols of fragility and femininity, he reminds the viewer of the humanity of his subjects — something that is too often set aside when upholding our heroes. Particularly, when considering the idea of the “strong Black woman,” narrow depictions of these historic figures can be damaging if immortalizing an unrealistic portrayal. In Love Letters, Charles White is able to consider our reverence for the tenacity of women like Angela Davis and Fannie Lou Hamer while also allowing space for and acknowledgement of the emotional and physical toll their public strength takes on their private lives. And as it was not uncommon for the artist to incorporate images of anonymous figures as a way to create art about and accessible to everyday people, White’s inclusion of an anonymous figure in Love Letter III can be seen as his offering this same care and consideration for all Black women.

1 comment

Nice review, but I’m afraid the figure in Love Letter II, does not resemble Angela Davis in face structure or skin tone. To me, she resembles a younger version of Fannie Lou.