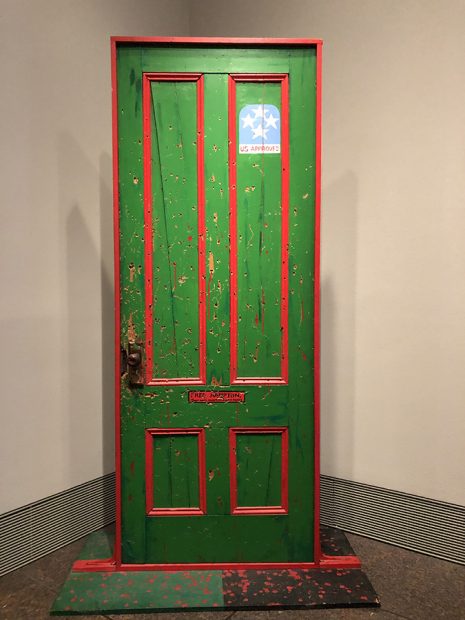

Professor Dana Chandler, Fred Hampton’s Door 2, 1975. Acrylic paint on wood. Photo Credit: Christopher Blay

Just beyond the entrance to Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power is a green door with red trim. The base is spattered in red paint, suggesting blood, and the door is littered with what are meant to be bullet holes. In the top right corner is an emblem with four white stars on a blue background, the words “U.S. Approved” emblazoned in red letters just below. The work is Fred Hampton’s Door 2, a sculpture by Dana Chandler from 1975. Door 2, because Chandler painted a previous version that was stolen from Expo ’74, an exhibition at the 1974 Spokane, Washington World’s fair. It is one of three doors in Soul of a Nation — as wide open a portal through which to consider this traveling show currently on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH).

I saw Door 2 for the first time last July when the Broad in Los Angeles hosted Soul. While there, I found myself returning to the door, and I hoped it would be it at the MFAH. Thankfully, Kanitra Fletcher, the MFAH’s curator for Soul, included Door 2 and placed it in a corner space all its own.

The paint and ‘bullet holes’ on Door 2 aren’t the actual physical evidence of the police raid that killed Hampton on December 4, 1969 (Hampton was 21 at the time), but they ascribe to it the resonance of a sacred relic. All at once, in the presence of the door and what it symbolizes, the power of the object becomes visceral, and imbues Soul with the kind of relic energy that makes seeing the show a necessary pilgrimage for our times.

The context of Soul is derived from the survey it presents of artists working in the early ’60s through the early ’80s, and the socio-political realities of those decades are inescapable in the works. Soul resonates the strongest when the art pulls directly from the decades’ headlines. The portal through Chandler’s Door is one of three pathways into the exhibition, each reflecting on the climate under which the works were forged — the legacy, persistence, and enduring consequences of which are revealed as we cross the thresholds the doors represent.

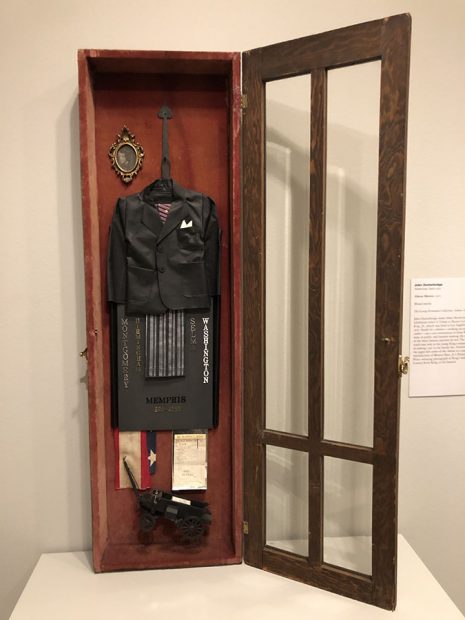

John Outterbridge, About Martin, 1975. Mixed media, 61 x 18 x 6.5in. The George Economou Collection.

John Outterbridge’s mixed-media assemblage About Martin, from 1975, is another such door. It is a cabinet with a glass door created for a 1976 Los Angeles exhibition titled A Tribute to Martin Luther King, Jr. The work’s funerary theme is inescapable: a laundry receipt declares “Paid in Full,” and the cities of Montgomery, Birmingham, Selma, Washington, and Memphis are spelled out, infused with the meaning of the marches and the deaths that were the price of confronting white power in each city. Below is an open carriage, not unlike the horse-drawn one that carried King’s casket in his funeral procession.

It is a door that opens into the civil rights movement and the ongoing struggle for justice and equality in the United States. Through it, we walk literally into spaces in the exhibition held by artists whose works offer a potent yet nuanced response from art in the age of Black Power.

Jack Whitten’s “Homage to Malcom, 1970.” Acrylic paint on Canvas or panel: 100 13/16 × 119 11/16 in. (256 × 304 cm) Promised gift by the Joyner/Giuffrida Collection to Tate Americas Foundation, Courtesy the Jack Whitten Estate and Hauser & Wirth.

“Abstraction” is one theme here, and Soul offers up works in this section that balance activism and art-historical context, more so than Soul does elsewhere in the galleries. For example, Homage to Malcom, Jack Whitten’s acrylic on canvas painting, is composed of concentric dark triangles textured with the teeth of an afro pick in one triangle, and smoothed out in others to an almost velvet sheen. It fits snugly with the Rothkos and the Newmans a mile away at the Menil Collection.

Homage is one of three geometric paintings hanging together, including Virginia Jaramillo’s Untitled (1971), a square-shaped painting of subtle intersecting lines emerging from the bottom of the painting and converging in a corner. The other is Ed Clark’s Yenom (#9).

Installation view of Soul of a Nation.

Jaramillo’s piece was first shown in the DeLuxe Show, back in 1971 at Houston’s Fifth Ward cinema of the same name. Other works in Soul, including Yenom, Sam Gilliam’s Carrousel Change, and Melvin Edward’s Some Bright Morning were also in the 1971 exhibition, adding a Houston connection that stretches the section of the show that focuses on Houston artists making work at the same moment.

Like Norman Lewis’ Processional (1965) elsewhere in Soul, the subtleties in abstraction belie an ever-present sense of the Black struggle. The paintings are never too far from the movement.

David Hammons, The Door (Admissions Office), 1969. Wood,acrylic sheet, and pigment construction. 79 × 48 in. Courtesy of the California African American Museum. Collection of Friends, the Foundation of the California African American Museum. CAAM Foundation Purchase, with funds provided by the City of Los Angeles, Cultural Affairs Department.

David Hammons’ The Door (Admissions Office), from 1969, takes us smack dab into the persistent obstacles and lack of justice and access that are at the root of today’s protest marches — obstacles that flatten even the most persevering spirits. The wooden door has a glass panel with that reads “Admissions Office,” and below the letters is one of Hammons’ body prints, created by applying grease to his body and imprinting himself onto surfaces.

The Door print composition has Hammons pressed against the glass panel, hands flat and mouth squished, looking in. (A similar work by Betye Saar, a contemporary and friend of Hammons, could have inspired The Door.)

With Door we can walk through to works in Soul that reveal how little things have changed. Like a cancer, we treat racism with the chemo of slow progress, believing it is fading away. What these works reveal is that every once in a while, society switches to other treatments (protests, marches, calls for change) because our national check-up keeps telling us the same thing. The cancer of racism is still here.

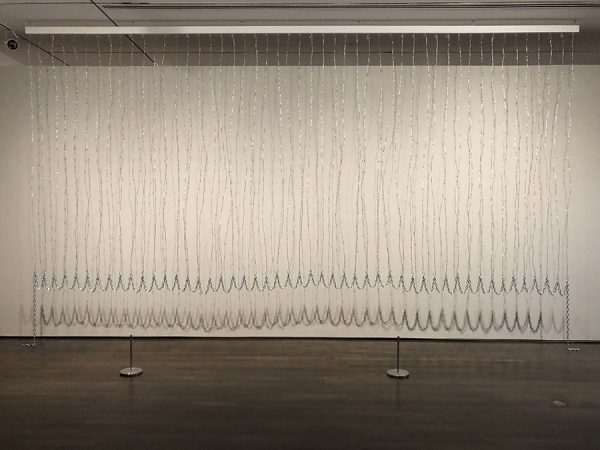

Melvin Edwards, Curtains (for William and Peter), 1969-70. Barbed wire and chain. Overall display dimensions variable. Lent by Tate Americas Foundation 2018.

It’s through Hammons’ door that we arrive at Melvin Edwards’ Curtain (for William and Peter), from 1969-1970. With hooks, chains, and barbed wire, the undertones of incarceration and the hooks of an inescapable fate are vivid. It’s prescient and ever true. Fifty years on, the imprisonment of generations of Black people in the most locked-up nation in the world is a dubious distinction.

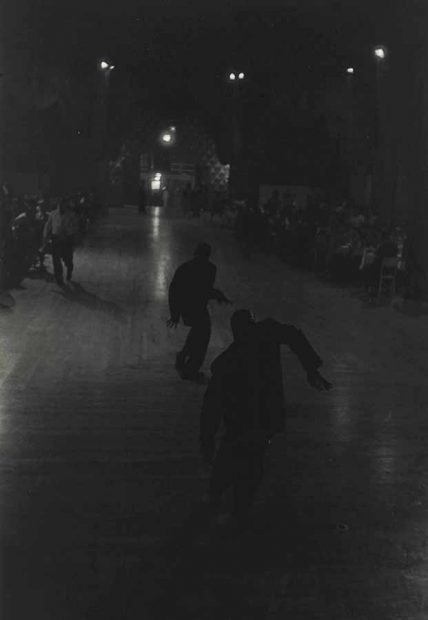

Roy DeCarava, Dancers, New York. From the Portfolio Roy DeCarava: Twelve Photogravures,1956, printed 1991. Image: 10 7/8 × 7 1/16 in. Gift of Joan Morgenstern in honor of Ray Carrington and the students at Yates High School.

Among the paintings, videos, and sculptures in Soul is a collection of photographs that connect the disparate sections of the exhibition together. The black-and-white, or more precisely pitch-black-to-deep-grey tonal range of Roy DeCarava’s prints are memorable. They create a semblance of muted memory or dreams — barely perceptible forms and shadows that emerge with a commitment to standing in front of the pictures.

Some sections differ from the presentation of Soul at the Broad. For one, the speech excerpts from Stokely Carmichael, MLK, and Malcom X on video monitors are installed in an alcove at the MFAH where the sound echoes and bellows into other sections of the show. Undoubtedly this is a Covid safety protocol to sidestep the use of headphones, but the distinction is distracting.

“Black Art in Houston” section of “Soul of a Nation”

I also can’t sense a strong enough path to the “Black Art in Houston” section of the exhibition, though the addition is notable. Even with the inclusion of strong works by John Biggers, Carroll Harris Simms, Earlie Hudnall, Jr. and others from this region, the section felt more like a disjointed off-ramp from Soul, rather than one that resonates with the rest of the traveling exhibition.

Soul is an apt survey of works by artists who belong in the regular canon of art history, not the ‘Black Art’ section. While some, like Romare Bearden, Roy DeCarava, and Faith Ringgold are frequently part of modern and contemporary art conversations, we shouldn’t need a degree in Black Studies (I don’t have one) or a traveling exhibition like Soul to discover them. With the MFAH’s extensive collection of Black artists, selections from that collection could be considered more often and in broader context than their limited inclusion in Soul.

Where I connect with Soul, I find myself at the intersection of life as a Black man, a father, an artist, and a writer. More often than not, the signal lights at this intersection are blinking yellow as I move across sections. But the constant is always Black. Black artist, Black Writer, Black Father.

The experience of Soul calls out to all the parts of me. As an artist it gives me pride, and the works and perspectives resonate. As a father it brings out all the anger, fear, and worry for the lives that are dear to me, in a landscape that only reveals superficial and incremental changes. As a Black man, a Black writer, it gives me courage and purpose.

To listen to a playlist made specifically for Soul of a Nation by musician and composer Quincy Jones, please go here.

‘Soul of a Nation: Art in The Age of Black Power’ is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston though August 30, 2020. The museum is open to the public and is following safety protocols.