This year was the third edition of Day for Night, Houston’s now-annual art, music, and light extravaganza. Hosted in the city’s Barbara Jordan Post Office, a 1960s Brutalist building on the north side of downtown, the festival has quickly earned a pedigree — last year’s event featured the first U.S. performance in eight years by electronic musician Aphex Twin, a set by Run the Jewels, and more Instagrammable art and light installations than you could shake a stick at. New to the 2017 festival was a Friday afternoon panel discussion featuring some known and underknown artists, activists, and people trying to grapple with art’s place in the world.

Though Houston’s strengths in the arts are many, a place where the city feels behind is in bringing smart, relevant creative speakers into town. Other destinations in Texas have us beat, particularly the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth with its Tuesday Evenings at the Modern lecture series. Day for Night’s Friday Summit, which was organized by Karen Farber of the University of Houston’s Cynthia Woods Mitchell Center for the Arts, attempted to fill in this particular gap and was perhaps the best collection of insightful, influential minds I’ve seen on a Houston stage. (It was also, in my opinion, the best part of the festival).

Laurie Anderson made her second trip to Houston in recent years for this summit, this time around discussing a project that was initially continuously rejected: she wanted to collaborate with a prisoner, creating an artwork in their likeness, but no prison would let its inmates participate. Though the project was ultimately realized as her 2015 installation at the Park Avenue Armory, her tale of the idea’s constant dismissal by the powers that be echoed the theme of resistance against authority. And Saul Williams, in his short, spoken word performances, expressed similar sentiments, drawing on ideas of technology and the way social strife and persecution give us the power to reform our societies.

Nadya Tolokonnikova’s presentation focused on the formation and work of Pussy Riot, emphasizing that DIY institutions give artists and activists the freedom to do the work they want to see in the world. She also spoke in conversation with Chelsea Manning about the inhumane treatment in U.S. and Russian prisons and the need for prison reform.

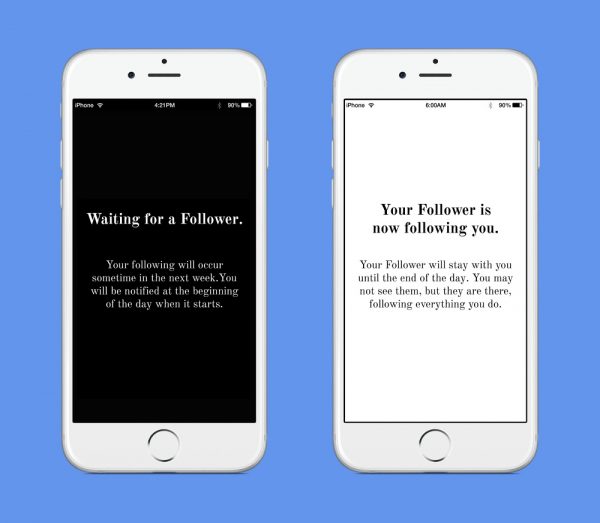

My big takeaway from Friday’s summit was the work of Los Angeles and Brooklyn-based artist Lauren McCarthy. Dealing with the convergence of surveillance, at-home technological advances, and body modification, McCarthy creates apps, wearable devices, and experiences that are at times helpful, creepy, and authoritarian. For example, a 2016 project promoted an app called Follower that provides users “a real life follower for day.” Tracking the user’s movements with GPS technology, McCarthy pursues them, staying undercover and out of sight. After the day is up, the user receives a single photo of themselves, proving that the artist was always there, always watching. Having an individual to follow you feels novel when it’s your choice; otherwise, it’s stalking, or, when done by a higher power, authoritarian surveillance. All of McCarthy’s works ask the implied question of how much encroachment on our personal freedoms and comforts we are willing to accept.

The other two days of Day for Night went on per usual. Most of the art and light installations were inside the post office building and were generally accessible with little to no wait time. I particularly enjoyed the pieces that felt like they could hold their own outside of being “festival art” — some gimmicky pieces work fine on a larger scale, while others just don’t have a hook.

With this in mind, I think Kyle McDonald and Jonas Jongejan’s Light Leaks installation was particularly powerful: comprised of multiple projectors aimed at a hanging net filled with mirrored disco balls, the piece held its space. The shimmering mass drew viewers in, and the pulsating patters of the projectors kept them engaged. Light Leaks was smart in its material usage — its combination of mirror balls and bright lights made sense and didn’t feel forced, and I could see it holding its own outside of the festival context.

Music-wise, the festival was strong. In addition to sets by Nine Inch Nails, Laurie Anderson, and of Montreal, Saturday’s lineup included a performance by Pussy Riot. The quintet, fronted by Tolokonnikova, spent part of the set clad in their trademark balaclavas singing protest songs in Russian, while the latter half of the performance was mainly comprised of songs from Tolokonnikova’s 2016 EP xxx. Later that night, Tyler, the Creator delivered a dynamic, honest set drawing predominantly from his Grammy-nominated album Flower Boy. Even through heavy rain, the crowd matched his energy as he sped through tender songs with harsh beats like 911 / Mr. Lonely and Where This Flower Blooms.

On Sunday, Solange’s performance was the standout. Her set at Day for Night impressed me even more than her concert at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa this past October — it felt like her Houston performance was freer and more genuine than her more weighty performance in front of Donald Judd’s concrete boxes. (That being said, both concerts were great; the set at Day for Night was just slightly better.)

This year felt like Day for Night had learned from its previous mistakes — many of the prior critiques I had of the festival were resolved this year. Even still, there was one thing that bothered me: one festival attendee who allegedly used fake passes to enter Day for Night was very publicly called out on the festival’s massive LED screens. Along with the man’s picture, the message on the screens read: “This is Jimmy Nguyen. He needs to leave the festival immediately.” Another showed his picture with simply the hashtag “#BOGUS.” While I don’t condone the use of fake passes or forgery, it’s the festival’s responsibility to not react like children when something upsets them. The projection of Nguyen’s image was uncalled for; to publicly dox someone for using a fake pass is unprofessional.

On most fronts, Day for Night has grown into a successful, enjoyable experience. The time of year is right (though some may consider it cold), the venue is visually and conceptually interesting, and the lineups have been solid. On top of that, the Friday Summit was a fantastic addition to the program, and I’m hopeful they’ll continue it in future festivals. Once they secure a more professional staff on the ground, they’ll have a festival that’s hard to rival.