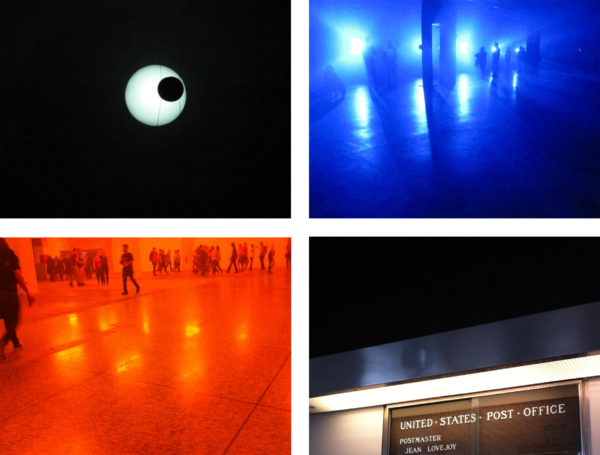

Houston is not good at preserving its spaces, but its creative community is often good at seizing opportunities to play with the city’s remnants and reorient its invisible, layered histories mid-transition. Recently, Houston’s former central post office building and surrounding campus were transformed by light, sound, and movement for the second annual Day for Night festival. Throngs of attendees from here and elsewhere (a majority of this year’s festival-goers came from New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Mexico City) converged in and around the 1960s Brutalist building nestled between train tracks, freeway, bayou, and buildings on the northwest edge of downtown. While most were lured there by certain favorite headlining musical acts, it was the de-centered audiovisual interplay in the expanses of its central structure that made the festival a truly unique sensory experience.

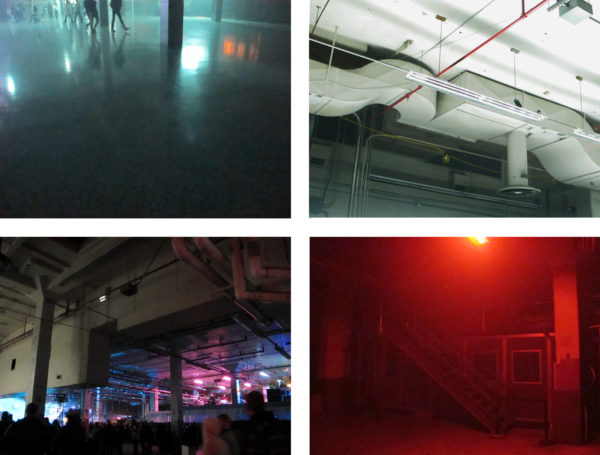

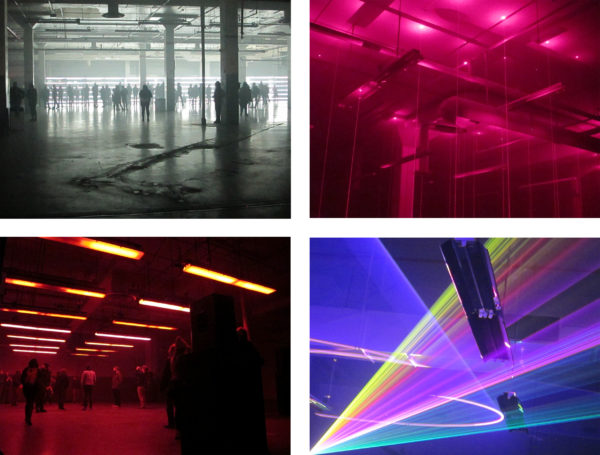

Day for Night’s unique location was more than a venue; it was an integral part of the festival’s structure, aesthetics, and, at least for me, conceptual overtones. The Barbara Jordan Post Office is not just some old, abandoned warehouse space, but a massive government building that was maintained and continually operational up until just last year. Its walls were not thin and shaking, its paint was not peeling, and its infinite number of hanging silver tube lamps were operational (though most were turned off). The hues and flashes of the festival’s various luminous art installations were reflected in polished terrazzo floors, and intermittently revealed glimpses of infrastructural lines, curves, shapes, and text. Rows of large concrete columns with painted numbers on them led up to high suspended a/c vents, heaters, systems of grouped and diverging electrical piping, and remnants of conveyor mechanisms and organizational systems. While the exterior of the rectangular structure, emitting a changing sequence of colored lights in its vertical slats, looked a little like a giant CPU, the interior confirmed that, yes, the building indeed had served as the city’s massive input/output system for a half-century before this audacious hack.

Many of the eleven indoor audiovisual artworks, curated by artist Alex Czetwertynski, interacted with the building’s structural elements and artifacts, activating intersections of the archaic and futuristic, solid and ephemeral, real and unreal, architecture and anarchical. The placement of these installations in different spaces throughout two floors was well considered, allowing flow, subtle overlap, and some respites of quiet dark space—all without dictating paths. At least a few of the visiting artists made conscious, creative use of the unique existing elements. The contemporary light sequencing for Limb’s Octa was installed within old hanging rectangular lamp fixtures (all the removed fluorescent bulbs gathered together at one column at the piece’s perimeter was a nice little touch, I thought). Nanotak’s Highline–with white light sequences moving across a long corridor of mirrored constructions in sync with clustered sound textures–was accompanied by a hulking sculptural ventilation system snaking along the full length of the piece high above it (though it was only visible in nearly subliminal flash illuminations). Tundra’s Outlines created parallel and intersecting lines with a grid of red lasers framed by a long row of the building’s columns, while Jon Durst’s laser piece Axelrad more playfully interrogated hanging lamps and walls with organically moving, multi-colored beams.

Most of the visual and synaesthetic works in the festival, including the projected and sculptural pieces outside and visuals at each of the four performance stages, interacted with their environment in interesting ways not possible in white cube galleries or traditional theaters. It’s easy for the old-minded art world to dismiss these kinds of works, most of them abstract, as trippy decoration rather than “Art,” or to view the openness simply as a lack of curatorial clarity. But I thought it worked really well, especially experienced as a whole, and I saw more enthusiastic engagement among festival-goers than I often do at art openings. There was frequently a long line of folks patiently, happily waiting to see United Visual Artists’ very good enclosed installation, Musica Universalis—and I’m positive few of them knew anything about the piece or the UK artists. Museums would kill for that kind of curiosity and faith. And I think more progressive multidisciplinary arts orgs would kill for the miraculous success of the ambitious festival in creating a world of interesting, experiential surprises without dictated path, rules, didactics, dissuasion of camera use, or even much indication of intended orientation.

The downtown post office space was a fantastic choice for locating this year’s evolving, de-centered collage of music and images—even for those without a connection to its long history as a communications hub. I’m impressed that everyone I’ve talked with seems to have experienced a completely different festival—that’s a major success in my eyes. I’m impressed by the organizers’ commitment to spotlighting a variety of light, video, kinetic sculptural, and sound works alongside higher-profile music performances. And I very much admire the festival organizers’ commitment to changing its location each year. The latter is something that I personally refer to as a “self-construct button”—a built-in constraint that ensures continual change, surprise, and reinvention—for better or worse. That suits the ideals of this festival, of a rapidly changing culture, and of this continually churning city.