Houston’s Day for Night festival gets a lot of national press attention for the audiovisual art installations augmenting its music line-up, as it should. Each year, its curated selection of immersive installations illuminate and reverberate in the spaces and times between concerts and drinks. The art alternately dazzles and calms, and collectively centers the eclectic, shared experience in one cosmic constellation. The art is a smart second priority for a music festival. In fact, its second billing below the music headliners may actually help to disarm and open the art experience.

Because of my interest in the roots and currents of experimental, interdisciplinary arts, I’d rather flip the conceit here and report on Day for Night as an annual, two-day, pop-up survey of international contemporary art works that deal with light, image projection, sound, movement, space, and public interaction, and it’s conveniently augmented by great music performances and drinks. Through that lens, Day for Night is a truly unique art endeavor, and one that leapfrogs many of the physical and philosophical pressures that mar museum and gallery presentations of similar works. I appreciate the lack of didactics, instructions, guards, and space constraints in the old downtown post office building where Day For Night was recently held for the second time. Its vast, open spaces allow for one’s own approach, positioning, and interaction with the works, and also create interesting in-between chambers.

In Day for Night’s latest audiovisual exposition a couple of weeks ago, I caught works by 19 artists and groups from around the world that I wouldn’t have otherwise experienced. This included some really impressive and inventive stuff, and even the less successful works were interesting within the collection. I noticed trajectories from historic experiments in “visual music,” kinetic sculpture, and sound art of the past century, and I connected cultural currents across the various pieces.

Outside by Mexico-City-based collective Cocolab was a nice work of site-specific, musically moving geometric abstraction — its choreography of white-light lines (and synchronized music/sound) interacted within a group of static columns. New York’s Hovver studio created a different light/structure interplay with Liminal Scope — a row of large, hanging physical rings, each containing a subtly shifting intersection of colored light.

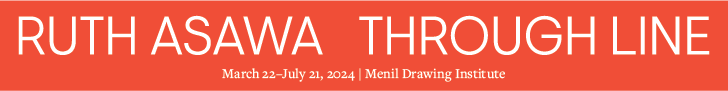

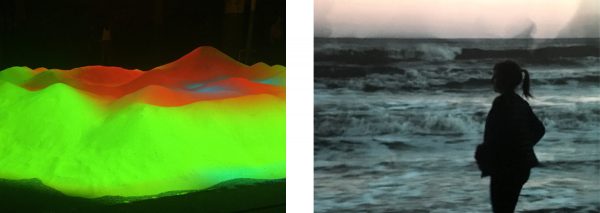

A trio of the smallest, simplest works in the festival provided reflective respites, reorienting land, sea, and sky. Gust by French artists Théodore Fivel and Freeka Tet was a small, mountainous landscape made of sand with ever-shifting areas of brilliant, projected colors upon its peaks and valleys. Threshold, by Houston-based Lina Dib and collaborating programmer Taylor Knapps, presented a wide panorama of ocean and sky, with which one’s close movements created momentary wind-water disruptions abstracting the horizon. Kyle McDonald and Jonas Jongejan’s Light Leaks — a festival favorite — cast moving, mapped light upon a suspended net containing a large number of mirrored disco balls. The effect was a magical sky environment of a million moving points of light around the central static sculptural cluster.

The inclusion of the political, conceptual piece Deconstructed Anthems was interesting. This installation by Ekene Ijeoma — a first-generation Nigerian-American artist born in Fort Worth and now based in New York City — acknowledged societal frictions by way of a reframed “land of the free.” Inside a series of slatted glass walls, a grand piano played (without player) The Star Spangled Banner 15 times, each time removing notes at the rate of increased mass incarceration from 1925 to now. As I walked inside the lit glass, stared at the empty piano bench, and listened, words of contemporary contradiction spoken by poet Saul Williams during the festival’s opening day talks echoed back to me. As I walked away and heard the incrementally reduced national anthem blend and disappear into the sound textures of surrounding installations, I knew that this complex undercurrent would stay with me.

The most “filmic” of the festival’s installations was the three-screen Hîbridos by Vincent Moon and Priscilla Telmon. One entered through a sort of tunnel of illuminated, translucent scrims, following percussive sounds and the smells of candles and incense, to finally emerge out of the triptych itself into a room of chairs, stools and tables in front of an ethnographic collage of Brazilian rituals. This collage of multiple-screen film sequences is the first iteration of an ongoing experimental documentary project combining bits of music and movement filmed in Brazil over the past three years.

Finally, I’ll also mention a great, live, multiple film-loop performance that was not within the group of curated installations but rather part of the stage performance of the band Godspeed You! Black Emperor. Though festival listings were vague, I’m pretty sure it was Montreal-based expanded cinema artist and frequent Godspeed collaborator Karl Lemieux who worked atop a scaffolding with three 16mm projectors and a number of original, short, black-and-white film loops. Lemieux’s timing of loop activation and deft superimpositions and transitions — created by his hands obscuring the various projector lenses — were organically synced with the atmospheric ebbs and flows of the group. (I don’t just count this among my favorites of the festival’s visual works because I love film, but it is worth noting that this was the one and only appearance of the analog medium I witnessed.)

While Day for Night is far from perfect on the whole, it gets some important things right about presenting time-based art in the 21st century: it suspends definitions, it darkens spaces, it opens interaction possibilities, and it encourages activations between different forms, concepts, and works… and adds some talks, music, and drinks along the way.

2 comments

Thanks for this great review. What would you like to see more developed in the future?

This is incredible.