Nasher Public: Linnea Glatt: Of Moth and Rust at the Nasher Sculpture Center, September 30 – December 3, 2023

Because of the striking visual memory of the recent eclipse that passed over the United States on October 14, when I see fluttering orbs of light filtering between the leaves of the trees of the Nasher Sculpture Center on Olive Street, I expect them to be carved into identical crescent shapes. I was out for a weekend stroll with a friend that day, and we were blithely critiquing the lawn ornaments that were on display in Dallas’s Hollywood-Santa Monica neighborhood in anticipation of Halloween (not enough 12-foot skeletons, or, maybe, too many 12-foot skeletons). While walking, we were given a chance to view the eclipse through a telescope offered politely by a resident.

As I peered into the viewport, the man told me, “You can see the sunspots.” He was right; I saw three little wrinkles on the flat, bright orange orb that coalesced into darkened blotches. The shape of our sun was perfectly round, like it had been painted on an animation cell and backlit. It almost looked to be some kind of computer rendering. It had absolutely no dimension to it, appearing princely flat.

Linnea Glatt’s celestial spots are not illuminated in this way. They are precisely masked into perfect circles, but their encrusted surfaces have a soupy quality, even as they impersonate the texture and dimension of possible gas or terrestrial objects. Four of them lay on the ground, and a 13-foot-tall white curtain hangs on the wall opposite the plate-glass streetscape, looking out onto Downtown Dallas. The bottom of the curtain has been acidified, or somehow degraded, to a similar rusty orange at the metal objects on the floor.

The connection that Glatt has made between astronomy, placemaking, and the interaction of natural materials serves as an ideal introduction to the Nasher’s grand survey of land art, which sits in the main exhibition space, just past the Nasher Public gallery.

****

Groundswell: Women of Land Art at the Nasher Sculpture Center, September 23, 2023 – January 7, 2024

I think the necessary planning, geometry, mapping, cartography, and logistics of the land art movement is what draws me to it. Conceptually, I struggle to accept it. Using land as the material for art objects, in some cases, feels antithetical to art making. Land tends to accrue value with time, as it is a commodity. This genre of art is also challenging in the institutional sense. Making work at the scale of land requires feats of energy and labor that break expectations that art should be delicate or sized to a gallery. This exhibition manages to present the work through artifacts as well as documentation and photographs, without physcially replicating all of the works cited here. The Nasher can do this and does it well, namely because the permanent sculpture garden outside symbolizes its commitment to sculpture both in and out of the gallery.

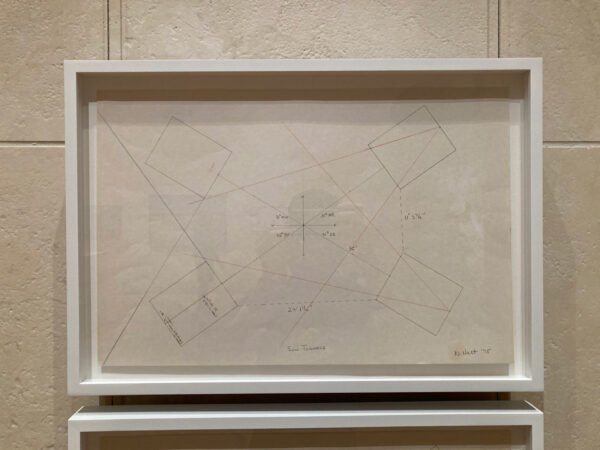

Nancy Holt, “Untitled drawings for Sun Tunnels,” 1975, graphite and colored pencil on paper. Courtesy of Holt/Smithson Foundation

The work on view here regularly engages the relationship between what is being exhibited on the ground and its place in the cosmos. Nancy Holt enlisted astrophysicist Les Fishbone to align her Sun Tunnels with the sunrise and sunset of the summer and winter equinoxes. Holes drilled atop the cylinders reflect the constellations of Draco, Perseus, Columba, and Capricorn.

Mary Miss, “Battery Park Landfill, 1973,” printed 2023, photo mural and two black-and-white photographs mounted on board. Courtesy of the artist

Mary Miss similarly, in the Battery Park Landfill in 1973, erected plaques of wooden slats that formed a large, sunset-shaped procession of circles. Battery park is an interesting site: sitting at the southern tip of Manhattan, it is artificial, constructed by sand dredged from the Hudson River. Back then, Battery Park was a sandy beachfront, whereas now it is paved and landscaped. Today, it is difficult to imagine any stretch of Manhattan being free of urban development.

Also in the main galleries, Alicja Kwade’s Les Sièges des Mondes features several chairs forged in bronze, which have natural stone orbs placed about them. Obviously granite and marble are excellent facsimiles for the gas giants, because their pasty hues can contain a multitude of colors; if you select the correct vein of your chosen specimen, whorls and rings perfectly appear, as if they were formed in space. The chairs involved in this work are all relatively pedestrian, humble, and common. I’m guessing they have to be formed in bronze in order to handle the weight of the stone planets that sit atop and within them.

The astrophysical connection to the human body is both convenient and obvious. Our understanding of physics usually amounts to breaking moving objects down to little balls, which we can lump together at different scales until they can be described as something that our eyes will understand and our vernacular can describe. Consider this quote by Kwade, displayed at the exhibition:

“At present, by my estimation, I myself am a constellation of 5.5 x 1027 ancient atoms (as I am thirty-eight years old) with lots of electrons that are moving at almost five million miles per hour.”

Anna-Bella Papp’s sculpted tablets look like concrete, which has become a material used by designers as well as builders. It is brutalist, chromatically neutral, institutional, and functional, and is used by entities and for purposed for which these characteristics make sense, like by the government for roads. It feels hardy enough to handle, even though in reality it is brittle.

At least one drawing inside the exhibition addresses the irony of using land for art. Johnson’s Garden of Killing is a diagram for imagined land use: slaughterhouses with channels dug into the land that redistribute the blood into the ground. This is part of a series of 18 drawings that explore the various orientations of the social use of land, complete with liner notes. These diagrams are mostly ways to hand-wrench certain visual forms, particularly anthropomorphic ones, into land use projects. A strange melding of urban design and graphic design. The artist even argues that “harmless color dyes” could be added to all industrial pollutants, making their presence in our wild water supply visible and therefore enabling the citizenry to recognize them. Re-coding the color of land and water, while interesting, seems inefficient and potentially toxic. Johnson’s drawings mix genuine imagination with wizened satire.

The artists featured in Groundswell: Women of Land Art are captivated by the transformation of land into evocative images and infrastructure that beckons human passage. The enigmatic allure of these structures, often alien and otherworldly, serves as a captivating showcase.

Nasher Public: Linnea Glatt: Of Moth and Rust is on view from September 30 through December 3, 2023, and Groundswell: Women of Land Art, curated by Leigh A. Arnold, is on view from September 23, 2023 – January 7, 2024. Both shows are at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas.

William Sarradet is the Assistant Editor for Glasstire.