Para leer este artículo en español, por favor vaya aquí. To read this article in Spanish, please go here.

When someone mentions land art, the most iconic work that comes to mind is probably Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970). Much of the history of land art has been dominated by male artists like Smithson, Walter de Maria, or Michael Heizer (who Texans might recognize from his piece in the Menil Collection’s front lawn, Isolated Mass/Circumflex (#2), 1968/78), to name a few.

A new exhibition at the Nasher Sculpture Center, Groundswell: Women of Land Art, expands the art historical lens and reframes our understanding of this movement. Conceived and developed by Associate Curator Leigh Arnold, the show is consequential and ambitious. There are over 145 objects from 12 selected artists, all women working in the U.S. from the 1960s through 1990: Lita Albuquerque, Alice Aycock, Beverly Buchanan, Agnes Denes, Maren Hassinger, Nancy Holt, Patricia Johanson, Ana Mendieta, Mary Miss, Jody Pinto, Michelle Stuart, and Meg Webster.

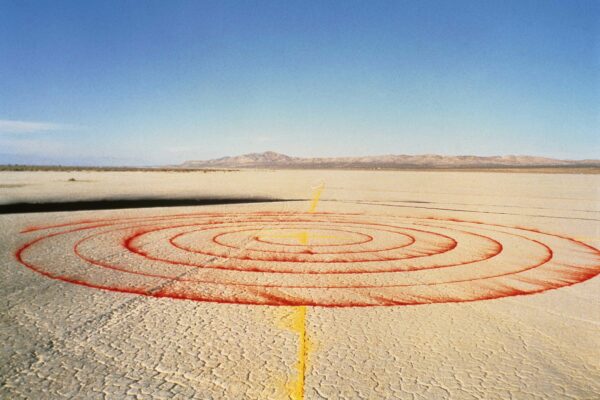

Lita Albuquerque (American, born 1946), “Spine of the Earth,” 1980, pigment, rock, and wood sundial, El Mirage Lake, Mojave Desert, California. © Lita Albuquerque, courtesy of the artist and Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles

Mary Miss (American, born 1944), “Battery Park Landfill,” 1973, wood, 5 ½ x 12-foot sections installed at 50-foot intervals, temporary installation in the space that was the landfill that became Battery Park City. © Mary Miss, courtesy of the artist

But how do you display an exhibition about land art without, well, the land? Groundswell features a mix of remakes and reimaginings of pieces that can be experienced within the confines of the museum, along with documentation via photographs, drawings, film, models, and related ephemera of temporal or site-specific works. For example, arguably the most recognizable piece in the show is Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels (1978), which is permanently sited in Utah and represented in the show through a model and accompanying drawings. With an abundance of material, the exhibit encompasses almost every crevice of the Nasher, both inside and out.

Nancy Holt (American, 1938–2014), “Sun Tunnels,” 1973-76, Great Basin Desert, Utah, concrete, steel, earth, overall dimensions: 9 1/6 x 86 x 53 feet (2.8 x 26.2 x 16.1 m), length on the diagonal: 86 feet. Collection Dia Art Foundation with support from Holt/Smithson Foundation. © 2023 Holt/Smithson Foundation and Dia Art Foundation/ licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York.

Despite the seemingly remote sites of some of the better-known artworks in the exhibit, land art isn’t just out there, somewhere in the far reaches of the country; it can be found, too, right here in North Texas. Two of the exhibit’s most notable examples are Patricia Johanson’s Fair Park Lagoon (1981-86) and a new work by Mary Miss commissioned by the Nasher and situated within the grounds of the museum’s sculpture garden.

Patricia Johanson (American, born 1940), “Fair Park Lagoon,” 1981–86, gunite, native plants, and animal species, dimensions variable, for the People, the Meadows Foundation, Communities Foundation of Texas, Texas Commission on the Arts and their private and corporate donations. Permanently sited in Fair Park, Dallas. © Patricia Johanson, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Michael Barera

Beyond the museum’s campus, just ten minutes away, is Johanson’s Fair Park Lagoon (1981-86). The lagoon itself was originally built in 1936 as a flood-control basin for Fair Park in South Dallas. But by 1980, it was in need of a cleanup. Using funds from the National Endowment for the Arts’ Art in Public Places program, the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts (now the Dallas Museum of Art, and located in Fair Park at the time), commissioned Johanson to create an artwork that could help restore the water feature.

Johanson created two outdoor sculptures that flank either end of the lagoon. On the southern end is Pteris multifida, which is the Latin name for Texas Fern, and on the opposite end is Sagittaria platyphylla, also known as Delta Duck-Potato, both species that thrive along the banks of water. The sculptures’ undulating frameworks reference the forms of the plants after which they are named. Both pieces are comprised of terracotta-hued gunite (sprayed concrete) elements that arch over or float on the surface of the water, creating a tangled mass of pathways.

Through the five-year-long design process, the project was revised six different times, to the artist’s dismay. But reflecting on Fair Park Lagoon thirty-seven years later, Johanson holds no grudges. “If we’re talking about aesthetics, it only matters to the artists and art critics. Nobody ever discusses the aesthetics of the Statue of Liberty, because it is too beloved and historical an object. You need to transcend the petty dialogue about what is ‘good’ and what is not, because the public will decide over time.”

Although the final piece does not align completely with Johanson’s original vision, it does achieve two of her goals: to create a functioning ecosystem for wildlife and to integrate people into nature with walkable pathways.

Installation view of “Groundswell: Women of Land Art” at the Nasher Sculpture Center, September 23, 2023-January 7, 2024. Featuring Mary Miss (b. 1944), “Stream Trace: Dallas Branch Crossing,” 2023, mirror polished stainless steel, dimensions variable. Photo: Kevin Todora, courtesy of the Nasher Sculpture Center.

Visitors to the Nasher can also experience a new land art work right in the museum’s backyard. Mary Miss’s Stream Trace: Dallas Branch Crossing (2023) is a site-specific artwork that follows the path of a buried stream that passes under downtown Dallas, including through the Nasher’s own sculpture garden.

Miss marked the path of the stream with a series of reflective Xs on stakes. “I was looking at this pattern of water going over sand or gravel, and this diamond pattern that was left. I ended up with this idea of trying to trace this stream with these mirrored elements, reflective elements that have the reflection of water. When you approach from the entrance of the garden you really don’t see anything. But when you get to the location of the installation, these things layer up to form a ghost of the stream.”

Where did the stream come from? The Dallas Branch was a tributary of the Trinity River, originating in what was once a freedman’s town (in the present-day neighborhood of Uptown Dallas). But sometime in the early 20th century, that community was built over and the stream was encased in a concrete culvert.

The artist laments, “we’ve removed ourselves so much from the environments we live in, especially in cities.” Through her current work with her nonprofit, City as Living Laboratory, Miss is making people more aware of the systems, like this stream, that are all around us but often invisible.

The public can follow the path of the stream beyond the walls of the Nasher by participating in a series of artist-led stream trace walks, or take self-guided walking tours to learn more about the history of the land along the banks of the Dallas Branch and about the people who once lived in these areas.

Groundswell: Women of Land Art is on view at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas through January 7, 2024.

2 comments

Great read. Sounds like a show worth visiting to see.

An unfortunate update re Land Art: https://hyperallergic.com/866527/iowa-museum-plans-to-demolish-mary-miss-land-art-installation/?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=D012224&utm_content=D012224+CID_55f67b5dc88d36ac9be403471f2c7a23&utm_source=hn