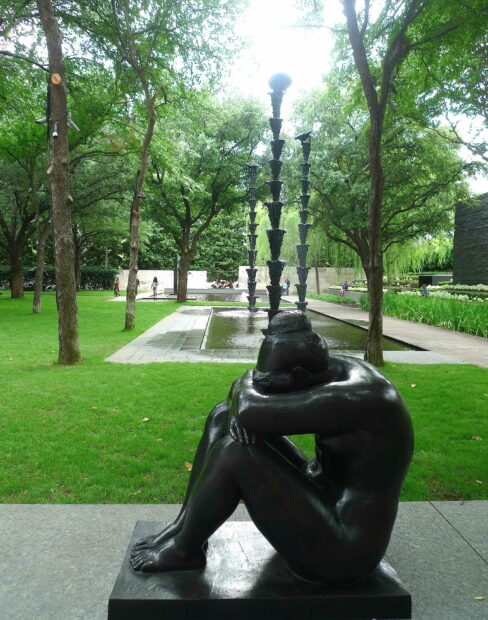

Lynda Benglis, “Bounty, Amber Waves, and Fruited Plane,” 2014 (detail of one fountain in the Nasher Sculpture Center garden), bronze, each column 25 feet 7 1/2 inches x 2 feet x 2 feet (307 ½ x 24 x 24 in.; 781.1 x 61 x 61 cm), courtesy of the artist, New York. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Lynda Benglis’ (b. 1941) bright, poured latex paintings made directly on the floor posed a dramatic challenge to the austere Minimalist aesthetics of the 1960s and 1970s. As her paintings made with foam increasingly obtained vertical mass, the artist seemed to merge painting and sculpture.

Lynda Benglis, “Contraband,” 1969, pigmented latex, overall (irregular) 3 × 116 ¼ × 398 ¼ in. (7.6 × 295.3 × 1011.6 cm); overall (thickness of latex) 1/8 in. (0.3 cm), New York, Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Whitney Museum. The Whitney classifies this work (which is not in the exhibition) as a sculpture.

Benglis also achieved notoriety for a nude photograph of herself with a double-sided dildo that ran as an Artforum ad in 1974. It was the subject of vicious criticism and resulted in the resignation of five Artforum editors. Benglis then made an edition of metal casts of the dildo (see this illustrated example and essay in Christie’s in 2017), one for each editor who resigned. (I wish she had named each cast after an aggrieved editor). Thus one can make the argument that Benglis was always a sculptor at heart.

The photograph had an enormous impact, affecting artists such as Cindy Sherman. Its landmark status was recognized by a New York Times Magazine article in 2019, which deemed it one of 25 art works that “defined the contemporary age” (Sherman didn’t make the cut). For an overview of Benglis’ career, see M. H. Miller in ARTnews.

The exhibition Lynda Benglis at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas features a protean assortment of the artist’s recent sculptures, and is on view through September 18, 2022. The works were selected by the artist in conjunction with Associate Curator Leigh Arnold, who also wrote a substantial and informative brochure for the exhibition.

From King of Flot to Quartered Meteor

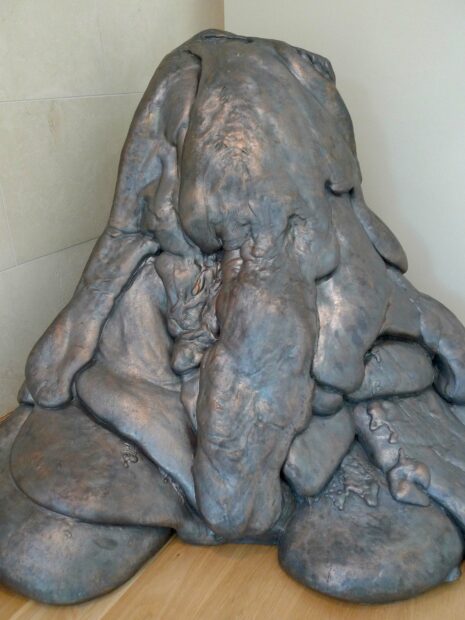

Lynda Benglis, “Quartered Meteor,” 1969 (cast 2018), bronze, 57 1/2 x 65 1/2 x 64 1/4 in. (146.1 x 166.4 x 163.2 cm), courtesy of the artist and Cheim & Read, New York. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

This bronze version of Quartered Meteor originated as a work made in 1969 called King of Flot. The latter sculpture was made by pouring successive layers of black, white, and gray polyurethane foam over one another. Benglis was not attracted to foam as a material in and of itself, but she was attracted to what she could do with foam:

And I thought, well, this foam also is a very stupid way of expressing something, and tactilely it’s not that interesting but you can make something interesting in spite of it. I’m not attracted particularly to the material but I’m attracted to what it can do. It’s not like wax or like metal that you’re really attracted to (Smithsonian Archives of American Art, “Oral History Interview with Lynda Benglis,” Nov. 20, 2009).

Lynda Benglis, “Untitled (VW),” 1970, pigmented polyurethane foam, 48 x 69 ½ x 41 ¾ in., private collection. Photo: H. Harp, flickr. I was unable to obtain an image of “King of Flot,” which was destroyed when it was cast in lead. I have substituted “Untitled (VW),” which demonstrates the high legibility of the individual pours.

Casting such ephemeral works as King of Flot (which is illustrated in black-and-white in the brochure) in metal is a way of making them durable, as well as inserting them into a prestigious continuum of artworks made of valuable metals that stretches back to the ancient world.

Relative to metal, polyurethane foam has the puffy qualities of a marshmallow. Benglis in fact took pains to accentuate the puffiness of her poured foam sculptures. (On this point, see Arnold’s essay in the brochure.)

There is definitely something strange about seeing a form that was originally made of foam cast into metal, because metal could not have achieved these shapes through the same process (by pouring successive layers of molten metal atop one another).

Rachel Taylor, discussing the Tate’s lead version of Quartered Meteor, has suggested that this transformation from foam to metal is “a deliberate attempt to subvert and make uncanny the material presence of the objects” (See: “Lynda Benglis, Quartered Meteor). It is certainly ironic to transmute foam to lead, bronze, and other metals, given the disparate inherent qualities that foam and metals possess.

This alchemy also encourages new readings of the object. According to Richard Marshall, “Quartered Meteor suggests a molten mass that has entered the earth’s atmosphere and slammed into a corner” (Richard Marshall, Lynda Benglis, Cheim & Read, New York: 2004). No one, on the other hand, would describe King of Flot as a heavy object, much less as a meteor.

Bounty, Amber Waves, and Fruited Plane

Lynda Benglis, “Bounty, Amber Waves, and Fruited Plane,” 2014, bronze, each column 25 feet 7 1/2 inches x 2 feet x 2 feet (307 ½ x 24 x 24 in.; 781.1 x 61 x 61 cm), courtesy of the artist, New York. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Lynda Benglis is from Lake Charles, Louisiana, where she grew up on the water. She was always “excited” by water and the idea of buoyancy and was interested in fountains before she ever made one. The experience of scuba diving changed the artist’s conception of water. Benglis describes scuba diving as akin to “going back to the womb.” (See the Storm King Art Center video that treats the 2015 exhibition Lynda Benglis: Water Sources, which included all of her fountains.)

Benglis’ three identical fountains, whose individual names evoke the lyrics of the song “America the Beautiful,” are situated in a large pool in the Nasher garden (in the above photograph, two people are on a wooden walkway that passes over the pool).

In a conversation regarding the iteration of these three fountains at Storm King in 2015, Benglis told Nora Lawrence that she regards the forms of these fountains “as a kind of totemic work, an endless column with water.” Benglis references Brancusi’s famous Endless Column, a smooth column made out of symmetrical units that is meant to suggest infinity. Benglis’s work, by contrast, has a deliberately rough texture (made by spraying polyurethane foam). Additionally, each element of her columns serves as a container for a pool of water.

Lynda Benglis, “The Graces,” 2003-2005, cast polyurethane, lead, stainless steel. Photo: A Place Called Space blogspot.

The forms utilized in the three fountains exhibited at the Nasher are derived from a smaller work called The Graces, fabricated out of cast polyurethane. When she visited the Acropolis as a young girl, Benglis was fascinated by the caryatids, which she thought had “an ice-like quality.” Benglis liked the polyurethane that she used for The Graces because people thought it looked like glass, which she associated with ice, and thus with frozen water. She longed to make The Graces into a fountain, in order to seemingly combine both solid and liquid water. (See the Art21 video linked in the 2021 Artnet News article “If a Waterfall Freezes, How Do You Read It?”)

At the 2015 Storm King exhibition, a brilliant, pink-red column titled Pink Ladies (For Asha), titled to commemorate the sister of Benglis’ life partner Anand Sarabhai, was paired with two columns called Pink Ladies. The individual components of the fountain were inspired by a kite Benglis saw at a kite-flying festival at Ahmedabad, India, where Asha was her host. For multiple installation photographs of the fountains at the 2015 Storm King exhibition, see Artnet News.

In a 2015 interview with Karen Rosenberg in Artspace, Benglis declared that her fountains were essentially conceptual continuations of her poured paintings: “These ideas of the pour and the ideas of the fountain were one and the same to me — I just wanted the water to extend the idea of the pours.”

Lynda Benglis, “Bounty, Amber Waves, and Fruited Plane” (detail with cascading water), 2014. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The experience of weightlessness and the loss of direction during scuba diving impacted how Benglis thought about water. Discussing the iteration of Bounty, Amber Waves, and Fruited Plane exhibited at Storm King, Benglis noted: “Water itself can be bountiful and flowing upward. I think of Bounty [her generic term for these three fountains] as a living growth or an explosion of water that is frozen in bronze, but also emits this water.” Benglis thus associates bronze with frozen water (akin to the polyurethane of The Graces).

Water is piped to the top of the fountains. As the pools of water fill, water drops down from one pool, splashing into another pool, which causes some water to shoot upward (at the same time that other droplets of water are falling down). The utilization of multiple pools causes water to go up and down simultaneously, replicating — in some sense — Benglis’ disorienting experience of scuba diving.

Lynda Benglis, “Bounty, Amber Waves, and Fruited Plane” (detail with spray), 2014. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

A significant amount of water sprays out from each fountain, which serves to humidify and cool the air in the general region of the installation.

Lynda Benglis, “Bounty, Amber Waves, and Fruited Plane” (distant view with Aristide Maillol’s “Night” in the foreground), 2014. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

When Benglis exhibited Bounty, Amber Waves, and Fruited Plane at Storm King, the three fountains had a golden patina (as can be seen in the Artnet photos linked above). For the three fountains exhibited at the Nasher, Benglis chose a more traditional black patina, which is similar to Aristide Maillol’s Night (in the foreground of the above picture). According to Arnold, as a consequence of this dark patina, “Benglis relies on water to give the sculpture its own luster and further the illusion of an object continually in formation and deformation.”

Lynda Benglis, “Bounty, Amber Waves, and Fruited Plane” (silhouette between trees), 2014. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Benglis’ fountains never look more totemic than when they are silhouetted against sylvan clouds and steel-and-glass skyscrapers, framed by a brazen necklace of trees.

Elephant Necklace Enlargements

Lynda Benglis, “Elephant Necklace,” 2016, glazed ceramic, 37 elements, 137 in. (439.4 cm.) in diameter as arranged in a circle. Photo: hamptonsarthub.com. (Not in the exhibition.)

As is often the case, the artist makes multiple associations with the ceramic pieces that make up Elephant Necklace. They range from roadside detritus to fossils to relics from religious myth, and Benglis configured them to evoke a necklace. Their forms were inspired most directly by blown-out truck tires, such as those commonly found on highways. The black color makes it easy to read these ceramic forms as damaged tires.

Benglis says these sculptures could also be associated with “fragments from mammoths’ trunks of an ancient time. Or perhaps they resemble strange umbilical cords cut after the expulsion from the Garden of Eden.” See the Ogden Museum of Southern Art’s website.

One of the three large sculptures in the Nasher exhibition is a modified enlargement of a ceramic sculpture in Elephant Necklace.

As the Nasher brochure notes, Benglis has a fabricator make a mold of each ceramic she wants to enlarge. A wax version is made from each of these molds, which is then scanned in 3-D, enlarged to the desired size, and 3-D printed “in a puttylike material.” After Benglis fine-tunes this printed model, a mold of it is made, from which the finished sculpture is cast in brilliantly reflective metal.

Lynda Benglis, “Elephant Foot: First Foot Forward,” 2018, white Tombasil bronze, 48 x 64 x 61 1/4 in. (121.9 x 162.6 x 155.6 cm), courtesy of the artist and Cheim & Read, New York. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

Elephant Foot: First Foot Forward was the first enlargement (and the first metal sculpture) derived from Elephant Necklace. This is an enlargement of piece #58.

Of the three bronzes in the Nasher exhibition, Elephant Foot: First Foot Forward, is the easiest to imagine as a blown-out tire, in part due to its smaller scale.

Grooves in the center even evoke tire tread. Tombasil is a highly reflective copper and zinc alloy. The irregular surfaces of the sculpture create funhouse-like distortions of viewers and the surrounding architecture.

Lynda Benglis, “Power Tower,” 2019, white Tombasil bronze, 89 x 72 x 64 in. (226.1 x 182.9 x 162.6 cm), courtesy of the artist and Cheim & Read, New York. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

At more than seven feet high, it is hard to picture Power Tower as a blown-out tire — its scale makes it just too imposing to imagine it that way.

Power Tower is an interesting work from any angle.

From this angle, it seems to rise up from a coiled base.

From this angle, I can even imagine an angry elephant.

Lynda Benglis, “Yellow Tail,” 2020, Everdur bronze, 53 x 96 x 74 in. (134.8 x 243.8 x 188 cm), courtesy of the artist. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Like Power Tower, Yellow Tail’s large scale makes it difficult to read as a blown-out tire. From this angle, it resembles a lazy 8.

Its golden sheen is remarkable; in the above photograph, it is partially reflected in the glass.

This angle affords the greatest sense of the piece’s rhythmic flow, as a kind of crazy roller-coaster.

From this angle, it is hard to assess how all of the parts of Yellow Tail fit together.

This photograph and the next one were taken inside the Nasher building, looking out to the garden. In the distance, one can make out parts of two of Benglis’ fountains.

From this angle, Yellow Tail has a serpentine quality.

Paper and Chicken Wire Sculptures

Lynda Benglis, “SB#3,” 2017, cast sparkles on handmade paper over chicken wire, 37 x 30 x 15 in. (94 x 76.2 x 33 cm), courtesy of the artist and Cheim & Read, New York. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The Nasher exhibition also includes five very fragile-looking sculptures (barriers prevent one from getting too close to them) made of handmade paper stretched over chicken wire. I don’t find them very interesting, particularly in comparison to the series of bedazzled knots that Benglis made in the 1970s.

Benglis twisted the chicken wire into an armature and then stretched wet paper over it. She added sparkles on the sculptures to provide them with more sheen.

Lynda Benglis, “Woopee,” 2015, handmade paper over chicken wire, ground coal with matte medium, acrylic medium, and glitter, 33 x 20 x 14 in. (83.8 x 50.8 x 35.6 cm), courtesy of the artist and Cheim & Read, New York. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Woopee, the only one of these sculptures with a name instead of a number, is the most austere in terms of color, though it might have the most glitter.

Conclusion

The Nasher’s Lynda Benglis exhibition features choice metal sculptures and fountains that are products of a long conceptual and stylistic evolution. Her chicken wire and paper sculptures can also be placed into a long continuum, though I do not regard them as among her best works in paper. Benglis’ extraordinary metal pieces make the exhibition worth a visit.

It is always a pleasure to experience an oasis like the Nasher garden in the center of a city. The trees, grass, and water create a pleasing micro-climate — it really feels like walking into another world.

While looking at the exhibition and writing this review, I also thought a great deal about water. Essential for life, water is also strange, beautiful, and highly variable. Looking into the pool pictured above, one can simultaneously experience the transparency, opacity, and reflectivity of water, all of which are subject to wind, to the vibrations caused by people on the wooden walkway, and by the organisms that inhabit the water.

Lynda Benglis is on view at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas through September 18, 2022.

***

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator.