Last week, as I was making the rounds to catch up on shows that were about to close in preparation for January’s slew of openings, I struck up a conversation with a gallerist in one of the spaces I visited. After the normal pleasantries and questions about holidays, we came around to the subject of what’s been going on in the Texas art scene in the past few months. During this discussion, the gallerist asked me a question that I hate to say gave me pause: “What is the last truly great exhibition you saw in a Houston gallery?”

I’ll reluctantly admit that I was stumped. Maybe it was due to the lack of new shows to see in December, or maybe it could be attributed to my failing memory; either way, the talk devolved into why I couldn’t remember any recent outstanding shows and what that might convey about the fourth largest city in the US that I lovingly and proudly call home. (Of course, with a computer in front of me I can name the shows that impressed me the most: Jeremy DePrez at Texas Gallery, Jennifer May Reiland at guerrero-projects, Michael Menchaca at BLUEorange… .)

Upon deeper introspection, I started to piece together why the shows that really left their mark on me did so: Texas Gallery took a risk with DePrez by showing large-scale paintings that even the most adventurous collectors would have problems fitting into their houses; guerrero-projects’ exhibition of Reiland’s works put center stage the allegorical sex, violence, and messiness of society that is so often missing in purely commercial gallery shows; and Menchaca’s show at BLUEorange, on top of being filled with solidly crafted works, pulled no punches with its biting political critique. (Although I’m calling BLUEorange a gallery, it could just as easily be called an artist-run space. But I digress.)

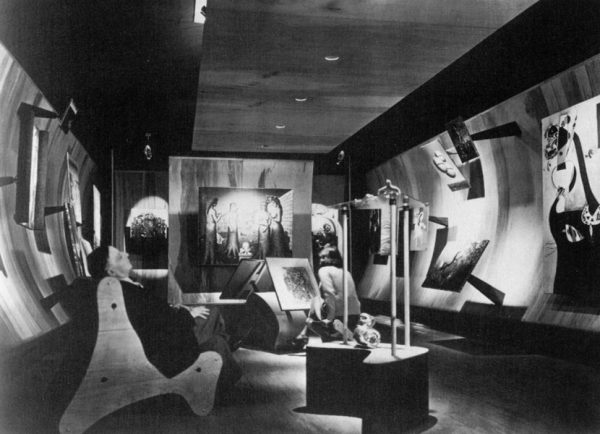

These three exhibitions did something that has become increasingly problematic for commercial spaces: they presented hard-to-sell, visually unpleasant, controversial art. Despite a need to sell, commercial galleries have long been the venues where artists could present their most radical, cutting-edge ideas: from Yves Klien’s 1958 empty exhibition at Gallery Iris Clert to countless shows at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century, artists relied on these spaces as an alternative to museums. (Not that Peggy was hard-up for cash.)

Frederick Keisler seated in the foreground of Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery, Art of This Century, 1942. (Photo: Berenice Abbott)

With the emergence of artist-run spaces and small to mid-size non-profits, however, it feels like many galleries have settled into the role of showing sellable art. And you can’t blame them: although galleries throughout Texas do still host performances and immersive installations, the economy expands and contracts, and it seems right now many spaces are in a sales slump. Recently, our country’s new administration, combined with the economic uncertainty that comes with governmental destabilization, has thrown a wrench in Texas’ private art collecting. So it’s no surprise that galleries are hedging their bets and showing their bread-and-butter artists to sustain themselves. They’ve always done this, mind you, but it’s normally been in tandem with a healthy dose of risk: you sell out a show of works by your staple artist, and that gives you capital to experiment with a show that might not go over as well. This business model starts to crumble when even your best artists aren’t selling like they used to.

And I think the perpetuity of exhibitions by artists already in galleries’ stables contributed to my forgetfulness of recent “truly great exhibitions” in Houston. There is a certain excitement — an eagerness that comes with walking into an exhibition and not knowing what you’re about to see. If you’re familiar with the artists in a gallery’s program, however, some of that edge is taken off, even if you like the work. For example, when I saw this fall’s Jeffrey Dell exhibition at Art Palace, I expected to walk into a show of beautiful, tricky, masterfully printed trompe l’oeil screenprints, and that’s exactly what I got. (This isn’t a bad thing. It also isn’t to say that a gallery and an artist you’re familiar with can’t surprise you with something unexpected, as Christina Rees attested to earlier this week.)

This effect does, however, make it more difficult to be wowed, because jaw-dropping wonder is sparked by the unexpected. When trying to work though this phenomenon with a friend, they suggested that one way to get around this blockade is to reassert the deliberateness with which I see art. My day-to-day work involves reading countless press releases for galleries and all art spaces across the state, staying abreast of shows, news, and other art-related things in the world, and making constant value judgments about what I should or shouldn’t spend my time on. It’s both a privilege and a curse to see so much art, because it breeds a special sort of weariness akin to that of art fair fatigue. It’s easy to lose a sense of presentness when looking at art, to be lost in your own mind’s blur at the expense of what’s right in front of you.

Consider this both a wish list and a New Year’s resolution of sorts. Galleries remain a crucial part of the art ecosystem by both introducing emerging artists to new audiences (audiences that can, ideally, afford to compensate them for the work), and by providing mid- and late-career artists spaces to show their newest work. We can’t fault galleries for doing what they have to to stay in business any more than we can fault artists for creating sellable work. We can, however, reexamine our expectations about the art we come across. I, for one, am going to use this year as a time to jettison the goggles of presupposition and familiarity in hopes of rediscovering the artists and galleries I thought I knew. I hope you’ll join me.

2 comments

Agreed!

I didn’t get to see the installation at gray contemporary in HoustonTx, but it looks immersive