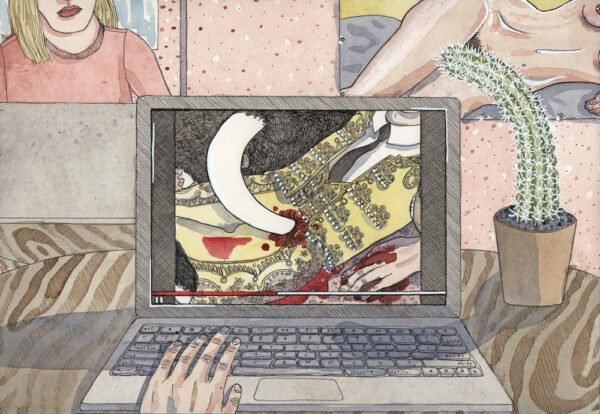

Jennifer May Reiland, Self Portrait Watching Bullfight Videos on Sunday Night, 2020. All images courtesy of Jennifer May Reiland.

A close-up shot of a large black bull digging its horn into a matador’s abdomen is the first thing we see in Jennifer May Reiland’s solo exhibition Carnage at Lawndale Art Center in Houston. Or rather, in Self Portrait Watching Bullfight Videos on Sunday Night (2015), we see the artist’s laptop screen playing a video of the bloody goring as she watches from inside her New York City studio.

Despite its small size, Reiland’s watercolor-and-pen painting is filled with poignant contrasts. Below the computer screen, the artists’ hand rests on the keyboard, while on screen, the matador’s hand clutches the ground in pain. On the studio’s back wall, a poster shows a woman’s naked breasts and belly, while in the video, the bullfighter’s ornately-costumed torso oozes blood. Beside the laptop, a potted cactus tilts suggestively toward the poster woman’s pubis, mirroring the curve of the bull’s embedded horn.

Life in today’s world involves a constant bombardment of images — many of them disturbing — and in Reiland’s picture, we watch as she watches. We don’t see the artist’s face, so it’s unclear if she views the video with horror or indifference. But in this self portrait, Reiland isn’t just a passive viewer or model: she’s the one putting the messiness of sex and suffering on display.

The effect is all the more unsettling because of Reiland’s meticulously detailed hand. Here, the bull’s fur, the matador’s costume, the table’s woodgrain, and even the cactus’s dirt are precisely outlined in careful crosshatches, circles, and lines. Each key on her keyboard has been lettered, and Reiland’s pastel colors are almost cheery, and thinly applied. The artist’s delicate style contrasts sharply with her provocative content, and a frequent sense of horror vacui ensures that nearly every corner of her surfaces is compulsively covered.

Like so many of Reiland’s paintings, the laptop scene is curiously mediated. The bullfight on the screen introduces a separate place and point in time, condensing the reality of a tranquil Sunday studio night into the drama of a torturous bullfight. In other images, TV and phone screens and the front pages of magazines, newspapers, and tabloids all bring separate people, places, and events into the action of Reiland’s compositions, effectively layering disparate histories together.

These juxtapositions complicate and contextualize a reading of Reiland’s work. In the artist’s 26-foot long frieze Martyrs Part II (2019), televisions broadcast footage from Princess Diana’s fatal Paris car crash and the September 11th attacks on World Trade Center. These and other types of global news media inject a jarring element of realism into some of Reiland’s dreamiest pictures. They also collectively form a sort of survey of the artist’s life experiences and interests.

Reiland’s fascination with bullfighting is a result of her time in Spain. The Houston-born, New York City-based artist moved there first as a study-abroad student in college, and later as an adult with her Spanish husband. However, in both cases, the artist lived far from the central and southern regions of Spain where bullfighting is still practiced.

“My whole experience of living in Spain has always been being really attracted to aspects of Spanish culture that are not really related to the regions that I was living in,” Reiland explained in a recent video call. As in her picture of bullfighting seen through a computer screen, the artist’s pictures see their subjects from a distance, and that distance allows space for her imagination to work.

“It’s meaningful to me to recombine some of these historical moments and figures,” Reiland said. “People say that my work is very chaotic because there’s a lot going on. But what I’m trying to do in my paintings is to cut things out to reveal some sort of connection.”

Often the connection in Reiland’s work is between types of women and the ways that they weather trauma. From martyred saints to fallen celebrities, many of Carnage’s paintings are of women who have been discredited and discarded by society. Some, like Marie Antoinette and Marylin Monroe, are well-known, but others have largely been forgotten by time. Reiland excavates these figures in her extensive historical research and re-envisions their lives in her artworks.

In Juana La Loca Cat Hallucination (2020), a young Queen Juana of Castile crouches in the corner of a stony cell. Like so many of Reiland’s heroines, Juana’s story is shadowy and tragic: when she became dangerously close to the possibility of taking power in medieval Spain, Juana was declared insane and imprisoned by her father in a convent, where she remained until her death. In Reiland’s portrait, Juana’s window is filled with cartoon strip-like vignettes from the queen’s troubled life. Ever inventive and interpretive, the artist translates Juana’s turmoil into the form of a ghostly cat apparition hovering to the queen’s right.

In another painting, Empress Carlota Remembers her Domains in Mexico (2020), the 19th century Belgian princess — who looks just like Reiland’s Juana — stands at what appears to be Juana’s same stone window. She reaches toward a map of Mexico, where scenes from her and her husband’s brief, ineffectual rule of the country float. After her husband’s assasination by firing squad, Carlota’s story ends like Juana’s: in grief and supposed madness. Reiland’s painting of her includes aspects of that darkness, but it also shows Carlota as a thoughtful, beautiful woman who is able to conjure and reflect upon her own life.

Regardless of whether they’re remembered by history or not, Reiland sees these women’s stories as fertile creative ground that’s worth commemorating and contesting in her works. Her pictures of women are not so much documentary portraits as gestures of a sort of imaginative empathy, where historical facts and artistic interpretations collide.

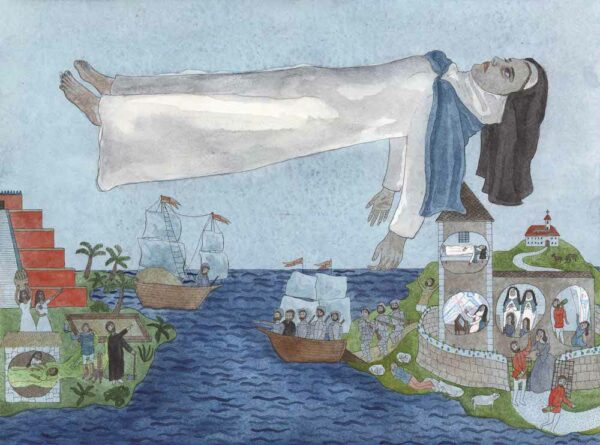

A final, lesser-known woman portrayed in Reiland’s paintings is María de Jesús de Ágreda. In her celebrated written accounts, the 17th-century Spanish nun claimed to have teleported herself to the New World several times through her mystical powers, though she never left her convent in Spain. Like María, Reiland exercises a kind of creative bilocation. In her artworks, she moves through Spain, Mexico, New York, Texas, and beyond, roaming time and space in search of new visions.

On view at Lawndale Art Center, Houston, through April 24, 2021.