Janet Sobel: All-Over at the Menil Collection, similarly to the museum’s recent exhibition Chryssa & New York, reasserts and reinserts an artist into the art historical record. Janet Sobel, who is both a typical and atypical abstract expressionist postwar artist, reenters the museum space. Her work is typical in its engagement with automatism and surrealism, and atypical in its “outsider” status (she was untrained in art via the traditional routes of a BFA or MFA, beginning her career at forty-five, and then disappeared from New York City’s art scene in 1947).

Sobel poured and dripped, shifted her canvases (or other adventurous materials as backing) onto the horizontal plane, and covered them “all-over.” Sobel worked in a similar mode as Jackson Pollock (although the majority of works on display are relatively small, so too did Pollock sometimes drip on a smaller scale). In the exhibition brochure, Associate Curator Natalie Dupêcher clearly situates Sobel’s presence in exhibition spaces and in the critical record during her active years (despite her subsequent erasure), citing Clement Greenberg as recognizing Sobel’s “all-over [effect]” as “the first” he had seen, in addition to Jackson Pollock’s stated admiration for her work.

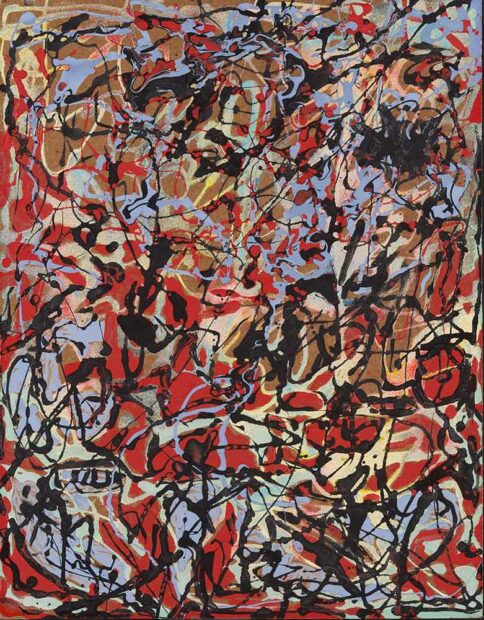

Janet Sobel, “Untitled,” ca. 1946–48, enamel and sand on board, 17 5/16 x 14 inches. The Menil Collection, Houston, Gift of Leonard Sobel and Family. © Janet Sobel. Photo: James Craven

The majority of her works in the exhibition straddle representation and abstraction, with faces appearing and receding from fields of vegetation and/or abstract compositions of skeins of paint. A vignette of four small drip paintings, without any representational references, stake her work alongside Pollock’s drips and sand-imbued works. Sobel’s use of sand creates textural shifts that reward close looking, particularly in Untitled (ca. 1946-47). Sobel’s work appears on canvas, board, bits of envelopes, sketchbook paper, and a page from a Museum of Modern Art exhibition catalog. The materials of daily life suggest a consistent and constant practice — reaching for what is available in the right now. An urgency to make the work and make it now.

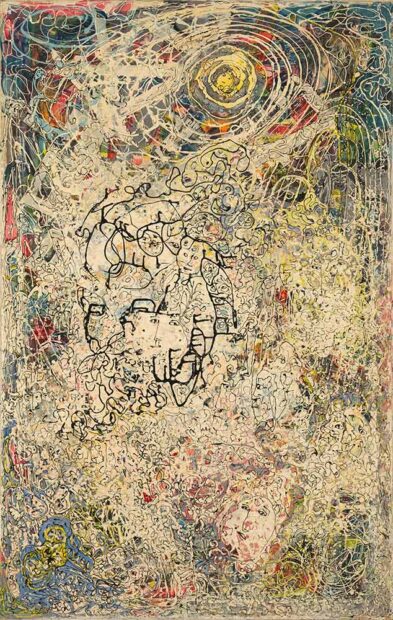

Janet Sobel, “Heavenly Sympathy,” ca. 1947, oil on canvas, 54 1/2 x 34 1/2 inches. Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas. © Janet Sobel. Photo: Edward C. Robinson III

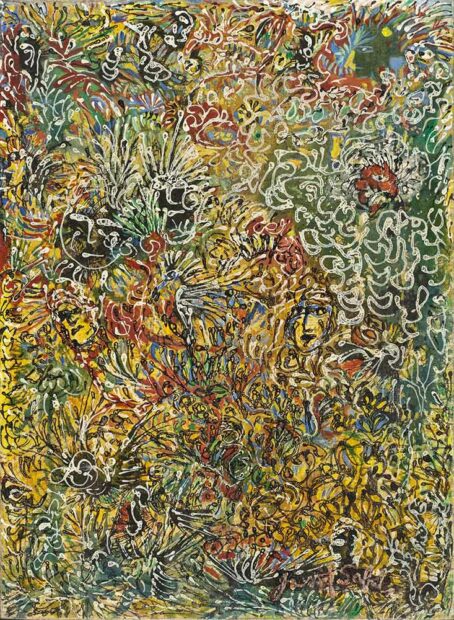

Janet Sobel, “The Burning Bush,” 1944. oil on canvas, 30 x 22 inches. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, American Art Acquisition Fund. © Janet Sobel. Photo: © Museum Associates/LACMA

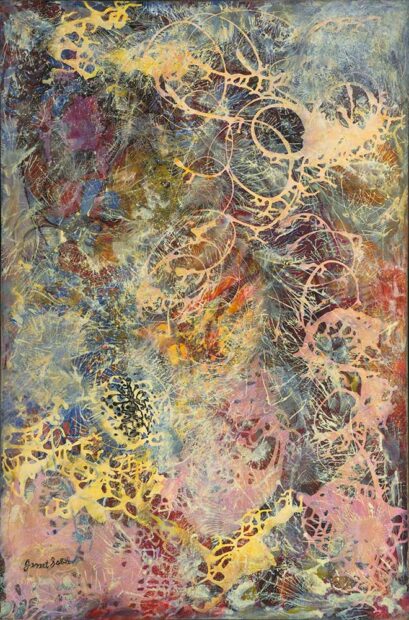

The National Gallery of Art’s artist page on Sobel expands on the Menil’s biographical information: Sobel, a Ukrainian immigrant, came to the United States after an anti-Semitic pogrom murdered her father. The National Gallery of Art also makes connections to Ukrainian folk art in Sobel’s figural work. While I did not immediately see this specific connection due to my own lack of knowledge, some of her smaller drawings, such as Untitled (ca. 1941), reminded me of illustrations from children’s books about Jewish history and religion. Jewish themes are mentioned in the exhibition brochure, and titles such as The Burning Bush (1944), Heavenly Quarrel (ca. 1942), and Heavenly Sympathy (ca. 1947) assert Jewish biblical connections. Those works, alongside Milky Way (1945) and Hiroshima (ca. 1948), in which the world (or galaxy) implodes and expands in paint, suggest an attempt to reconcile post war trauma (a shared abstract expressionist goal). In Milky Way, the galaxy and the everyday commingle or maybe implode: paint splatters like exploding stars and coagulates as if rings of milk on a breakfast table.

Janet Sobel, “Milky Way,” 1945, enamel on canvas, 44 7/8 x 29 7/8 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of the artist’s family. © Janet Sobel. Photo: © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

After viewing the exhibition, I visited the Menil’s surrealist galleries. Visual connections to Max Ernst, in particular, were legible, and the ability to see the Surrealist pieces and connect them to Sobel’s work enriched the experience of both galleries. On display near the surrealist gallery exit are two early transitional works (between surrealism and abstract expressionism) by Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko.

After viewing both galleries, Sobel’s works clearly argue for her repositioning in abstract expressionism’s foundational years. Pollock and Rothko’s early transitional works, exemplifying the abstract expressionists’ use of surrealism and automatism alongside their attempts to make universal claims of feeling or experience, make clear Sobel’s work participates in the abstract expressionists’ shared project. Ultimately, however, I found myself more drawn to Sobel’s visual connections to Wols’ It’s All Over (1946-47).

While the irony of Wols’ title and the title of Sobel’s exhibition is an accidental connection, both artists sought to make sense of (or make clear the utter lack of making any sense of) war and horror. Wols used paint in the wake of war to find a “formless” painterly loss; abstraction ciphers human disaster in his painting. In Sobel’s Hiroshima (ca. 1948), she manipulates her drips so that what is up is down and down is up; there is no clear gravitational pull, as she appears to have moved her canvas round and round to drip in all directions. Near the top emerges a bearded face within an ether-like cloud formation of paint, which is rounded like the top of a mushroom. Throughout the work, brushstrokes tangle with washes and smears of paint in the clouds and smoke. Wols’ and Sobel’s paintings seek a visual language to render devastation visible.

Installation view of “Janet Sobel: All-Over” at the Menil Collection, with “Hiroshima” on the far left. Photo: Paul Hester.

I was excited to learn about Sobel and, as I overheard other visitors make their own art historical connections, they also felt the excitement of discovery. For more about Sobel (and my review was informed by my reading of it), I recommend Sandra Zalman’s “Janet Sobel: Primitive Modern and the Origins of Abstract Expressionism” in Women’s Art Journal (Fall / Winter 2015).

Janet Sobel: All-Over, curated by Natalie Dupêcher, Associate Curator of Modern Art, is on view at the Menil Collection in Houston from February 23 – August 11, 2024.

2 comments

Great review! I like her Milky Way.

What was the curator’s goal in pairing Sobel’s work with the surrealist collection? I found the connections between the two very interesting and thought-provoking.