Eloy Torrez, “It’s a Brown World After All” [portrait of Cheech Marin, detail], 2006 oil on canvas, 60 x 60, gift of Cheech Marin. Photograph: courtesy of the artist. (Illustrated artworks are in the collection of The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art and Culture, the Riverside Art Museum, unless otherwise noted.)

In addition to a rotating permanent collection, a community gallery, and ample space for major traveling exhibitions, the center will generate scholarship and, through internships, it will train future museum professionals from regional colleges. Marin and local officials hope that it will help to bring about a cultural renaissance in Riverside, a majority-Latinx city with a population of around 330,000.

In this review, I begin by highlighting Texas artists in the inaugural installment of the Cheech’s permanent collection, which is called Cheech Collects. I compare this exhibition to Chicano Visions: American Painters on the Verge at the San Antonio Museum of Art (SAMA), the first venue on a long (2001-2007), high-profile tour of Marin’s collection that visited 12 cities, which I reviewed in Voices of Art (VOA) (vol. 10, #1, 2002: 16-18). I assess Cheech Collects in its entirety, and I examine the circumstances of the museum’s creation. Finally, I discuss the museum’s future plans and potential.

Texas in Riverside

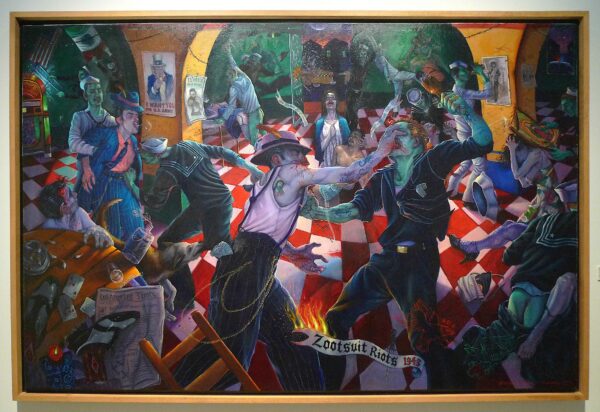

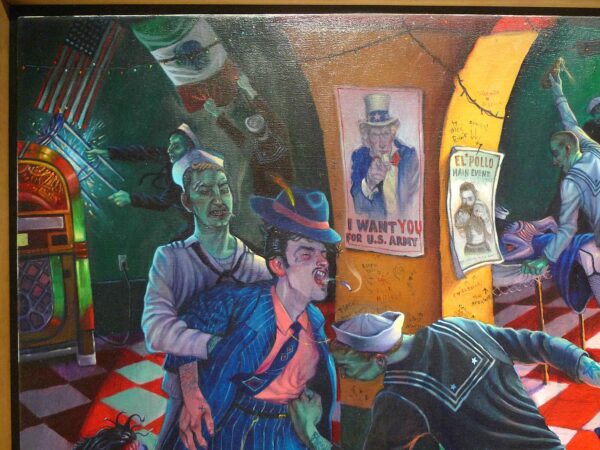

Vincent Valdez, “Kill the Pachuco Bastards!,” 2001, oil on canvas, 48 x 72 inches, gift of Cheech Marin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Perhaps the greatest revelation of Chicano Visions was Kill the Pachuco Bastards (2001), a painting by Vincent Valdez, the youngest artist in the exhibition. Everyone who saw it witnessed the emergence of a bright Chicano art star. As one of the highlights of Cheech Collects, I discuss it here at length. In my VOA review, I referred to it as:

… surely the show’s edgiest work. It depicts a no-holds barred bar-fight in which rapacious sailors savage a Pachuco joint in 1943. They violate every Chicano body and cultural emblem with unremitting barbarity. The painting is remarkable for: the dynamic expressiveness and superb characterizations of its varied protagonists, the lurid lighting effects, the complex space (including a tile floor that “rolls” like waves on an ocean) and the undeniable mastery that makes it possible to pack such dense (and meaningful) iconographic details into a compelling, clearly legible narrative.

In the center foreground, a pachuco fights a sailor who wields a broken beer bottle. The two protagonists are identified culturally by a rosary and dog tags. The pachuco’s twisted left hand, which is wounding in the palm, suggests righteousness through its evocation of Christ’s crucified hand.

Moving in a clockwise direction, we can see the self-fulfilling, prophetic headline of the Los Angeles Times on June 3, 1943 (the date of the first fight between sailors and pachucos), which declares “‘PACHUCOS’ cause crime.” Pachucos were deemed unpatriotic because their flamboyant clothing “wasted” fabric during wartime. The press actively instigated attacks on pachucos by characterizing them as violent, sexually depraved criminals. Inflammatory press accounts alleged that pachucos had assualted the wives and girlfriends of sailors. In response, during a period of ten days, enraged sailors boarded streetcars, entered businesses and homes, and beat and stripped pachucos. Sometimes they cut their hair, or burned or urinated on their clothing. In Kill the Pachuco Bastards!, Valdez represents sailors as the violent and rapacious group.

Catherine S. Ramírez notes that because they were bilingual and bicultural, pachucos “embodied an alien ambiguity during a period of heightened jingoism, xenophobia, and paranoia.” She argues that anxiety over gender and sexual fluidity was also a factor, since the aggressors enforced a “narrow definition of heterosexual and American manhood” (“Zoot Suit Riots,” Encyclopedia.com, accessed May 5, 2023). Their relatively long hair and flamboyant dress was considered unmanly, especially during a period of wartime austerity.

Also see History.com, the Zinn Education project, and PBS.

Pachucos were non-deferential and irreverent. In early 1942, just weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued the order for people of Japanese ancestry to be removed from western states and placed in concentration camps. In this period of racist extremism, pachucos served as convenient ethnic “others” for the sailors and other White racists to assault. (Valdez and I subsequently shared stories of racial profiling after the attacks on 9/11, which also resulted in hostility and violence against people of color.)

A pachuco situated under the round table has already been beaten and stripped of his zoot suit. Beneath James Montgomery Flagg’s classic Uncle Sam Wants you for the U.S. Army recruitment poster, a pachuco is being beaten by two sailors. They clearly regard him as an internal enemy rather than a fellow citizen and potential serviceman. On the far left, sailors attack cultural emblems: one hits the jukebox with a barstool, while another tears down a Mexican flag.

On the other side of the arched column, a sailor is raping a woman who is bent over a table, while two sailors throw a pachuco through a glass door. His hat flies in the air, juxtaposed against a bullfight painting in the background (ironically, bullfight aficionados threw their hats into the ring to celebrate a good fight).

Vincent Valdez, “Kill the Pachuco Bastards!,” 2001, detail of upper right. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Through the open door, we can glimpse some of the taxis that brought the sailors into the pachuco bar (some offered free rides). In the center, a beaten woman holds a beaten, unconscious man in a pieta-like pose. But with her upturned head, her desperate eyes, and her hands tightly clasped in beseeching prayer, she recalls Mary Magdalene. We see an imminent danger that she cannot. Behind her, the sailor in the dark uniform is striding forward with an upraised club. He is looking to hit someone’s head — perhaps he will strike the woman or her beloved.

On either side of the praying woman, banderoles read: “200 pinche sailors” and “kill the pachuco bastards.” The former refers to the estimated 200 sailors who rented cabs and who sought out and attacked Mexican Americans on June 4, which must be the date this scene depicts. Over the next week, racist sailors, soldiers, civilians, and even policemen (note the police car seen through the bar’s window) attacked zooters and people of color, while targeting Mexican American males in particular.

To the right of the striding figure, a sailor in a white uniform is kicking a pachuco. Behind them, a mural recreates the Mexican calendar artist Jesus de Helguera’s Amor Indio. This image of indigenous love stands in stark contrast to the rapacious violence that is taking place in the bar. Moving to the right, a sailor is urinating on a column, while another crashes an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe over the head of a pachuca. The sailors have a monstrous green cast, and this one is extremely green.

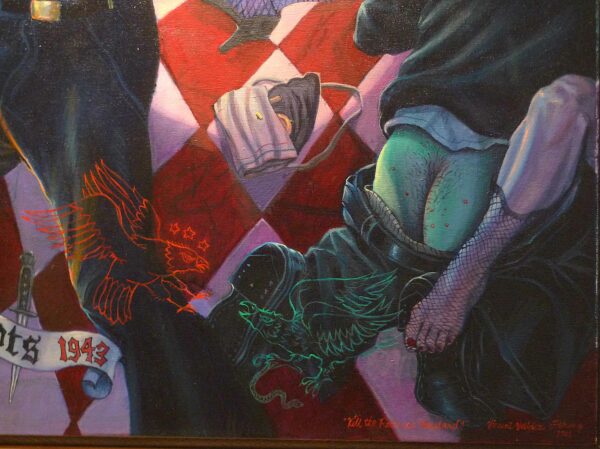

Vincent Valdez, “Kill the Pachuco Bastards!,” 2001, detail of lower right. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

In the lower right corner, as another extension of violence, a sailor is raping another woman. In the foreground, the fray is symbolized by a battle of eagles: a ghostly red U.S. eagle faces off against a green Mexican eagle.

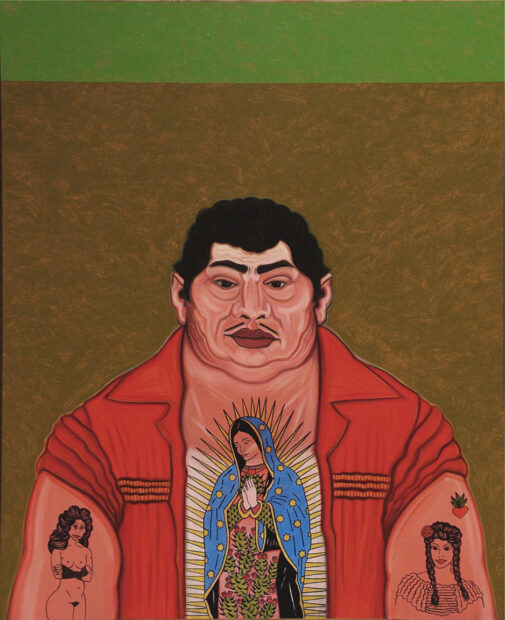

César Martínez, “Hombre que le Gustan las Mujeres,” 2000, oil on canvas, 54 x 44 inches, gift of Cheech Marin. Photograph: courtesy of the artist.

When César Martínez began making images of batos and rucas in 1978, he was particularly inspired by California artists such as Salvador “El Queso” Torres and José Montoya. He also drew from Alberto Giacometti’s solitary figures, and frontal images by Richard Avedon and Fritz Scholder. Additionally, Martínez acknowledges several abstract artists who influenced this series: Mark Rothko, Jules Olitski, and Kenneth Noland (one feature that remains from his study of these artists is a narrow band of color that he places at the top of his paintings). Martínez makes figures, “but the essence is abstract,” he says, “because it’s a very elusive ‘reality’ that I am searching for.”

Martínez’s images of people are not, strictly speaking, portraits. They are composite images. They are sourced from pictures from the 1940s and 1950s, when, as Martínez noted, Mexican Americans were regarded “as rebellious because of their dress. Clothing became politicized because it was seen as an emblem of difference, so it relates to racism.” This is evident in the above discussion of Valdez’s Kill the Pachuco Bastards!. (The above discussion summarizes part of my catalog entry on Martínez in ¡Arte Caliente! Selections from the Joe A. Diaz Collection. Corpus Cristi, TX: South Texas Institute for the Arts, 2004.)

Martínez has continued to refine his batos and rucas since 1978. He often makes variations on his favorite subjects. The three paintings discussed here are unusual in that they are from a brief period in which the artist utilized oil paint instead of acrylic, which is his usual medium.

Martínez’s Hombre Que le Gustan las Mujeres (The Man Who Loves Women) is one of his most popular images, owing to the juxtaposition of the three highly incompatible tattoos that the man bears on his body. Martínez has made three paintings of Hombre Que le Gustan las Mujeres, as well as smaller versions in different media and in prints.

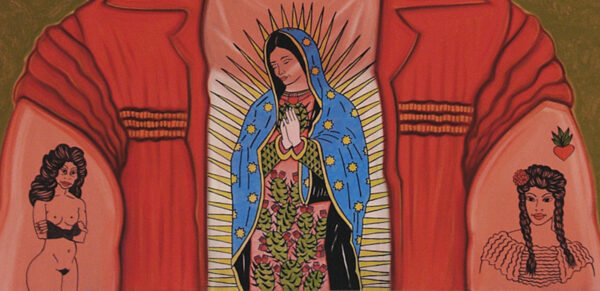

On his chest, the man has a large tattoo of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Oddly, her head is much darker than her hands, because that head is above the tan line on the man’s chest. He must habitually wear a low-cut muscle shirt (a.k.a. “wifebeater”). Due to this tan line, the rays that emanate from the virgin’s body somehow seem to illuminate his lower chest area.

César Martínez, “Hombre que le Gustan las Mujeres” (detail), 2000, oil on canvas, 54 x 44 inches, gift of Cheech Marin. Photograph: courtesy of the artist.

The virgin is facing the man’s right arm (on the left side of the painting). On this arm, he has a tattoo of a woman with bouffant hair who wears nothing except for fetishistic black gloves with cut-out fingers. She has red nail polish and red lipstick. One could hardly make a more sexualized image. Therefore, in the Catholic universe, she is “bad.” The Virgin of Guadalupe is rendered with her traditionally downcast eyes. Consequently, she seems to be averting her gaze from the tattoo of the nude woman, as if the image is too sinful for her pure heart to behold. Because her hands are clasped in prayer, she seems to be praying for the soul of the sinful tattoo of the fallen woman. On the man’s other arm, he sports a tattoo of a “good” Mexican American “girl,” one with braided ponytails, a frilly blouse, a rose in her hair, and a flaming heart floating above her. She is a clichéd image, much like the “Rosarita Bean girl” and other advertising icons meant to evoke Mexican wholesomeness.

It is hard to imagine that the man with these three tattoos does not possess a virgin/whore complex. Moreover, the two tattoo faces on each arm look so much alike that they could be depictions of the same woman, split off into divergent halves (both of which could be fantasies), and mediated by the centrally placed Virgin of Guadalupe.

Martínez rendered the man’s psychological bifurcation explicit in his second painting on this subject. Wrong-Headed Hombre (1989) features a man with three tattoos and two heads! His first version, painted in 1985, features a man with one head and very rudimentary tattoos. Neither of these first two paintings had a colored strip at the top. The Cheech’s version has much more sophisticated tattoos, especially the color version of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

Instead of her traditional rose-patterned linear motif on her pink dress, Guadalupe sports a prickly-pear cactus with numerous red fruits, which the Aztecs analogized to human hearts. Behind her hands, a large cactus with a red heart takes the place of her human heart. It resembles a barrel cactus, on which the Aztecs made early human sacrifices on their journey from Aztlán, their mythical homeland. See Mexicolore. Thus Martínez has added another layer of indigenous identity to the icon.

There is poignancy in the man’s corpulent, wizened face, and in the apparent softening of his body, which, given his bullish neck, was probably hyper-muscular when he got these tattoos. He is probably a psychological bundle of contradictions. There are, however, plenty of men with incongruous tattoos and psychological states, and, in Mexico, I have often seen divergent emblems juxtaposed together, such as a sticker of the Playboy bunny next to that of the crucifixion, or the Virgin of Guadalupe.

I asked Martínez how he came to select these three tattoos. He replied that initially he had “no theme,” just an idea to paint a man with tattoos, with the central one a chest-sized crucifix. But gradually, as he recalled to me, “the feminist emerged,” and he decided to make a statement about women through tattoos. “La Virgen,” he points out, is a woman and “a beloved, inviolate mother figure.” He adds that men, like the one in this painting, “advertise their attitudes by their choice of tattoos.” He refers to irony as “an effective, impactful device,” one that was absent in his original (unrealized) conception of this motif.

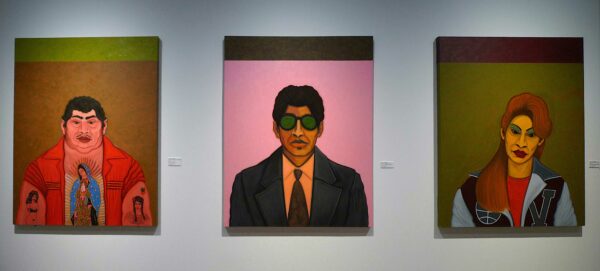

César Martínez, “Hombre que le Gustan las Mujeres,” 2000, “Bato con Sunglasses,” 2000, “Sylvia with Chango’s Letter Jacket,” 2000, all 54 x 44 inches, oil on canvas, and gift of Cheech Marin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Bato Con Sunglasses is a variation on one of the artist’s favorite motifs, which he refers to as “a staple, almost like a genre, within the series.” A man with sunglasses looks directly at the spectator, but we barely have access to his eyes, which are visible only as schematic outlines through his glasses. This version is wearing a suit and tie, which diverges from his earlier versions, which are more casually dressed.

Martínez shared the following text with me, which is a draft for his website:

Then there’s the ubiquitous Bato Con Sunglasses character which has become, I guess, this character [that] epitomized my idea of ultra-cool when I was a teenager. During my senior year in high school I affected sunglasses to hide behind and I buttoned up my shirt at the collar. Though I’ve never portrayed myself as a bato con sunglasses, I have been asked if it is me in some of them…. perhaps it is my affinity with the subject coming through. This cool bato con sunglasses character is very generic, mysterious and idealized, but in spite of all the ones I’ve done, this character remains an enigma, challenging and elusive for me.

Sylvia Wearing Chago’s Letter Jacket is the only version of this character that Martínez has rendered to date. The artist recalls that after making numerous images of batos proudly wearing their high school letter jacket, he wanted to do something different and “close that circle by depicting a girlfriend wearing her beau’s jacket,” which was a common practice when Martínez was in high school. The image in Sylvia Wearing Chago’s Letter Jacket came from a quick drawing Martínez made in a small sketchbook that “nailed a look I had been thinking of.”

Martínez recalls that women in his high school wore “big hair” and “heavy make-up.” He doesn’t remember any clothing that could be termed “distinctively pachuca,” since they wore clothing that was popular at the time, but, “like the males, they wore it with a special flair and attitude.”

In the draft text for his website, Martínez explains the rationale for his colored, abstracted backgrounds and his arbitrary use of color when rendering flesh:

By isolating the personages in a nuanced color field, I can make them very specific and unavoidable. Through selective use of color, the color field serves to enhance the mood or attitude that I want to convey and assumptions about colors can make color choice ironic. I was very much influenced by color-field painting during my formative college years, having been particularly taken by the nuanced work of Mark Rothko, Helen Frankenthaler, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski and, later, Chinese master Zhang Daqian. Fair to say they influenced those fields of color in my work. For the sake of appropriate context, I’ve referred to this field of color as an abstract landscape, the usual band of color at the top suggesting a horizon line. Often, my characters are not done in naturalistic skin color; that is my way of addressing discrimination of that sort and thus acknowledging it. Regardless of color, I still manage to make them look Chicano enough.

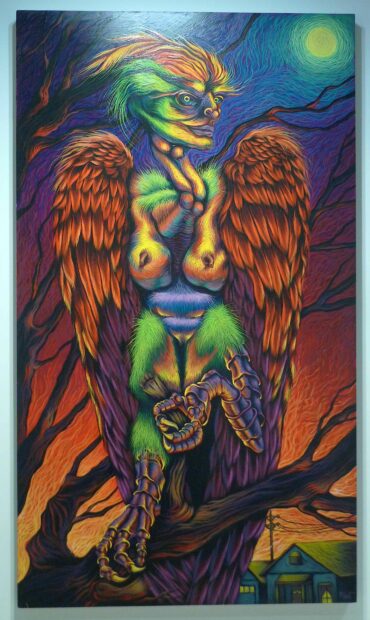

Rubio, “La Lechuza,” 2001, oil on wood panel, 84 x 48 inches, gift of Cheech Marin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Rubio once saw a lechuza, but he did not heed her, and he paid the price. He will never make that mistake again. I first heard this story at the Chicano Visions exhibition in 2001. I repeat it here as a cautionary tale.

In the Mexican American folklore of South Texas, the lechuza (the owl woman) is often regarded as an evil omen, something to be feared. Rubio, instead, grew up with a positive view of the lechuza:

… the description of the lechuza has been passed down over the generations. I learned it from my mother, Guy Rubio, who learned it from her father, who was from Mexico City. The owl was the only bird totem able to transcend into the underworld and bring back messages, to be interpreted by a priest or elder. From my mother’s point of view, the lechuza is a good omen, though established religions have demonized these spiritual beings. I was taught to respect the totem of the owl — as a way to interpret omens. Many other people, they are afraid of her. She is surrounded by superstition. They have described her as almost a witch. I have never looked at her as evil. I looked upon her as an omen that was trying to warn me, to serve me, to make me more aware of a particular time or place that I should be more aware of.

She is depicted as an apparition that most Mexicans and Chicanos here know. She is a large bird with the head and torso of a female human. There is an understanding that there is a spirit world.

Rubio recalls the fateful night he crossed paths with the lechuza:

On my birthday, December 3, 1987, I was near the Viramendi housing projects on the westside for a birthday party. On the way home, there was a thunderstorm, a rolling thunderstorm, and I sought shelter at the Vidaldi park pavilion. Next to that pavilion, there is a large tree. There were not many leaves on the tree. I heard this rustling, like there was wings, then I heard a crackle, then I saw this large shadow of a bird, way at the top of the tree. It was backlit, it looked down, and I saw it spread its wings. It was an unusually large bird in this tree, with human features.

I grew up hearing about folktales other parents used to scare children “If you don’t go to bed, the lechuza will get you.”

I ran to a phone booth and called my mother. She said, “Dios mio, whatever you do, don’t talk to her, and don’t look at her.” Out of respect for these animal totems, you take this sign just by seeing it. You get the lesson internally. It would be disrespectful to cuss, shout at it, or to throw something at it, which other children were taught to do. Parents in some families are scared so they give their children the wrong advice.

I turned around and I started walking away. After seeing this bird I was feeling it was some kind of message that was gifted to me…. Even after I saw it, I didn’t heed it. I went back to the courts on Christmas Eve. The lechuza was warning me to stay away, but I went back to Viramendi.

In a 2004 catalog entry, I noted the consequences of Rubio’s failure to understand the lechuza’s warning. Rubio was partying. A friend called him, and he turned.

Suddenly unable to stand, Rubio fell to his knees. No one knew what had happened. He thought he had been hit with a firecracker. His friends laughed. Rubio lifted his shirt and saw “lots of blood.” He was the victim of a drive-by shooting: “I was shot, I was on my knees, almost blacking out, and people behind me were singing Christmas Carols. I remember it being the weirdest thing — how can anyone explain the feeling you have when you are going to die?” (text for Drive By Shooting, a drawing made in 1994, ¡Arte Caliente!: Selections from the Joe A. Diaz Collection, Corpus Christi: South Texas Institute for the Arts, 2004, p. 38).

But Rubio did not die. The doctor told him: “Rubio, you are probably one of the luckiest men I have ever met. The bullet, which was headed for your heart, spun through the layers of tissue and exited through your back. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

That shooting, said Rubio, made his sighting of the lechuza “real.”

His mother advised him: “you need to be extra careful, that was a sign. That was a warning.” After the shooting, he took her advice:

I realized now that this was the message — to stay away from this area, to stay off the streets, to stay with family and friends. The lechuza is almost someone you have to become in tune with. We’ve lost our sense to understand this form of communication from another reality, from a metaphysical and spiritual world. We’ve lost our heightened sense of connectivity to these omens and signs. But after the drive-by, I respected it more than ever.

By depicting this icon, I hope this story will be passed on to future generations.

After the 2001 opening of Chicano Visions at the San Antonio Museum of Art, Marin invited Rubio to attend the openings of the exhibition in other cities, and to make connections with the local Chicano communities. He learned that the lechuza myth had national rather than merely regional scope: “I was surprised that Chicanos everywhere knew her legend… that she had traveled this far. People knew her story, some had even seen her.”

Rubio, “La Lechuza” (detail of head and breasts), 2001, oil on wood panel, 84 x 48 inches, gift of Cheech Marin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

The lechuza is rendered in Rubio’s signature style, with curvilinear lines that he first developed in a large (13 x 10-foot) painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe (1989) made for San Fernando Cathedral in San Antonio. Rubio, who was 20 years old at the time, found that it was “a natural way of me making marks on a large canvas.” Since Rubio did not get a good look at the lechuza, he rendered her face from his imagination. Rather than a kindly, benevolent creature, Rubio depicted the lechuza as a harpy-like creature. She is sexualized, in a very dangerous-looking manner.

The houses at the bottom are symbolic, because lechuzas inhabit neighborhoods, where, as Rubio notes, “they are needed.” Rubio recalls that his mother “would hear a lechuza in the backyard, and she would cancel a trip to Corpus.” Or she would tell him that he couldn’t go out. I asked if seeing a lechuza was like a hurricane warning. “Exactly,” Rubio replied.

The Queen of the Night, possibly the goddess Ishtar, c. 1800-1750 BC, mold-pressed terracotta plaque, 19.4 x 14.5 inches, British Museum, London. Photograph: British Museum. The colored reconstruction on the right is based on traces of paint on the original.

Many cultures have traditions that associate owls with women, darkness, and knowledge, including the Greek goddess Athena, whose emblem is an owl. But the closest surviving ancient parallel to Rubio’s Lechuza is The Queen of the Night, a plaque in the British Museum that is thought to represent the goddess Ishtar. It is probably from Babylon, from around the time of Hammurabi.

The goddess (identified by her crown and circle and staff motifs) has avian wings and talons and dewclaws. She is flanked on either side by owls.

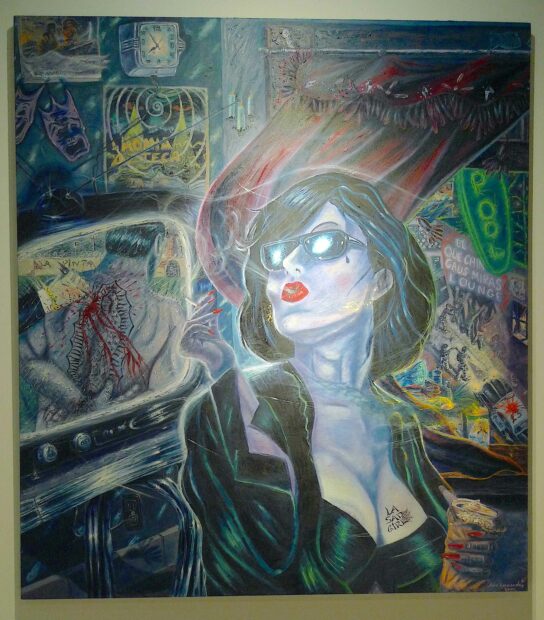

Adan Hernandez, installation shot with “La Bomba,” 1992, oil on canvas; “Drive-by Asesino,” 1992, oil on canvas (diptych, gift of Cheech Marin); “La Sad Girl,” 2003, oil on canvas, courtesy of Cheech Marin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Hernandez’s nocturnal paintings, which often feature scenes of violence, have been dubbed Chicano noir. I discuss the formation of his style and its connection to the film noir genre in my Glasstire article “Adan Hernandez Paints the Black of Night, Part I: The Birth of Chicano Noir.” In that article, I note that Hernandez fashions

nocturnal urban worlds whose beauty seemed to function as bait. All too often, it was just a lure or trap to expose some sucker to the very real dangers that were hidden inside of that flashy urban world. Just as a moth would be consumed by an irresistible flame, the hapless rube could be crushed in a car wreck, shot by an unseen bullet breaking through the night, blown to smithereens by an exploding bomb, or, for unseen reasons, become just another body crashing through a plate glass window and tumbling to earth. Or one might become a homeless man, sleeping on a bed of newspapers and broken dreams, bathed all night long by flashing neon lights that herald attractions that are forever just out of reach.

La Bomba and Drive-by Asesino were two of the four strong paintings by Hernandez that were also featured in Chicano Visions.

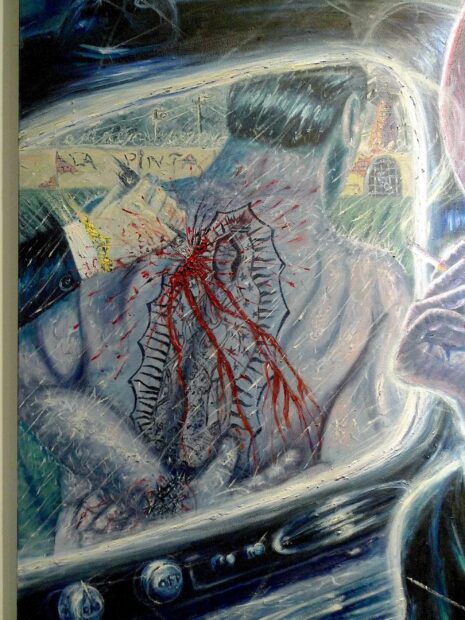

Adan Hernandez, “La Sad Girl,” 2003, oil on canvas, courtesy of Cheech Marin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

La Sad Girl, painted while Chicano Visions was touring, features a woman smoking a cigarette and drinking a beer. To her right, one can see the police raiding a Chicano nightclub. To her left, a television screen shows a prisoner who is being led to prison (visible in the background) with his hands cuffed behind his back.

Adan Hernandez, “La Sad Girl” (detail of television), 2003, oil on canvas, courtesy of Cheech Marin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

He bears a large tattoo of the Virgin of Guadalupe, which prisoners get in order to diminish their chances of being stabbed in the back by other Catholic prisoners (since that prisoner would have to stab through the virgin). But this unlucky prisoner is getting killed before he even enters the prison. A man in a business suit and a white shirt has no reluctance or religious compunction about stabbing through the Virgin of Guadalupe tattoo.

In addition to night scenes, Hernandez loved Mexican movies and posters, from Golden Age black-and-white classics to absurd, low-budget horror films, such as Momia Azteca (Aztec Mummy), whose lobby card is visible between the television and the clock. Fictively, the murdered prisoner could be La Sad Girl’s boyfriend. The artist told me that in real life the model for the painting was dumped by her boyfriend because he objected to her presentation.

Candelario Aguilar, Jr., “El Verde,” 2020, mixed media on panel, courtesy of Cheech Marin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Candelario Aguilar’s El Verde is one of Marin’s most impressive recent acquisitions.

In El Verde, Aguilar renders an outline of a Star Wars X-Wing fighter that traverses the large painting from the upper left to the lower right. This outline is partially dissolved and effaced. It shares this quality with many other partial images that mimic the appearance of having suffered deterioration during a long life on the street. Like a much-graffitied wall, the panel is a palimpsest that reveals many layers of labor, which includes several partial images, including the eponymous green Mexican wrestler standing on a tiled floor on the right.

Through the contrasting thick-and-thin lines and overlays of spray paint, one can make out (moving from right to left) the brown-yellow lower torso of Winnie the Pooh, the magazine and trigger of an assault rifle (in the lower center), pop-inspired spring flowers, and green grass. Images of life, death, and childhood are commingled.

I inquired whether these diverse elements had particular significations, or whether they were there by chance. Aguilar replied: “It’s both. Time and circumstances take their place in my work. Everything in life seems to be by chance.”

Aguilar’s works typically feature tension between abstraction and figuration, which he characterizes as “push and pull.” For the artist, it is a dualistic reflection of “the bilingual, border region environment that I’ve lived in for 50 years.” He adds: “To me, figural forms represent a grounding, a sense of reality and of the familiar.” For Aguilar, abstract forms, on the other hand, “represent freedom, a detachment, a break from the weight of reality.” He generally wants to have both elements in his paintings, and working out the proper balance between the two is one of the challenges of his art. The act of breaking up figural forms serves to render them more abstract, which is how the artist achieves his balance.

In the above process shot, taken at an early stage of work on the big painting, we can see at least six partial renderings of the Mexican wrestler El Verde. Aguilar was riffing on Andy Warhol’s paintings with multiple images of Elvis Presley. He doesn’t know much about wrestling, and he chose El Verde simply because he was green, a color associated with marijuana (which endows the grass in the lower left with another layer of meaning).

The collaged comic elements are visible directly behind the artist. As of yet, there is no inkling of the Star Wars X-Wing fighter. Most surprisingly for me, the scribbled black bar that divides the painting is already present at this early stage. The sound effects caused by the assault rifle, which are so familiar from Roy Lichtenstein and the combat comics that inspired him, will largely be effaced when the painting is complete. At this early stage, it almost seems as though El Verde is fighting against the assault rifle.

The assault rifle, the weapon of choice for mass shooters, is blocked off on the left by the vertical wall of childish scribble marks. That rifle — as well as the visual rendering of its sound effects — is increasingly contained by the various layers Aguilar adds to the painting. He almost buries it completely, but the magazine and the finger on the trigger remain, providing an almost hidden note of menace in an image filled with naïve and innocent forms. It is Aguilar’s way of saying that we can try to forget about gun violence, but the danger is always there, no matter where we go.

Aguilar’s goal is “an aesthetic that encompasses everything that is to be part of the border region.” Therefore, he says, his artistic vision is a compendium of border culture, one that is “beyond individual identity.” Aguilar characterizes his paintings as “a weaving, an orchestration” of a full range of mediums including: acrylic, oil, aerosol sprays, ink, soft pastels, solid markers, oil stick, fabric paints, and image transfers.

Aguilar explains why he uses so many mediums, materials, and forms of mark making:

From the very beginning it made sense for me to explore the possibilities of mixing it all up, like the human body made of bone, skin, hair, nails, blood etc. My work is made up of various mark- making mediums, creating the constant textural contrast, a push and pull between English/Spanish, Mexican/American, pizza/tacos, El Chavo del Ocho/Three’s Company.

For the artist, these forms of artistic mixing represent and reflect “a Frontera culture that is constantly mixing it up.”

Aguilar references art history, commercial media, film, and music. He combines this content with local iconography, which includes regional characters (such as the green wrestler), and such non-canonical influences as hand-painted signage, and his children’s scribbles and drawings. As major influences, he cites the following: George Lucas, Vincent Van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, Miles Davis, Conjunto musician Narciso Martínez, Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, Warhol/Basquiat collaborations, Rufino Tamayo, and Alfredo Bustinza.

Aguilar explains how film, music, and animation find their way into his paintings and installations: “imagery from the big screen or TV animation gets into my work” [in various ways]. These can take the form of “spaceships, color combinations, even phrases that could be applied as titles.” He notes a Steven Spielberg film called Ready Player One, in which a virtual world extends into the real world: “I’ve always liked the idea of cartoon animation walking around in real life.” Aguilar utilized this combination of realities, beginning in the mid-2000s, in works he refers to as his barrioPOP classics. This series of paintings includes Land of Peace (2007), Inside Job (2009), and Suite of the Freed Souls (2009). He characterizes this body of work as “barrioPOP with a surrealistic flavor.” Aguilar queries: “How else could I explain R2-D2 standing next to an appropriated Diego Rivera child playing the accordion with dragonflies and melting walls?”

According to the artist, El Verde was something of an artistic exorcism: “I struggled for quite some time while creating it. It just would not resolve, it kept requiring more and more work.” He worked on it for three months, and it was the last painting he completed before the Covid pandemic. He stopped work around January 21, 2020.

It also took some time for Aguilar to realized that it was finished:

The painting sat in my studio untouched for about 2-3 weeks. Walking by a piece and being able to ignore it is always an indication that I’m done and this is pretty much the case with all my work.

Aguilar elaborates on the mysteries of his art-making process:

I can see how it could look chaotic and maybe even disturbing. It turns out that I ended up dumping all my negative, positive energies, ideas and painting concepts into it, a sort of artistic dumping ground, a clearing of the mind. It’s almost always a mystery when starting an artwork because I never know what will come out of it. The importance of this painting for me is that I — unknowingly — was able to clear my mental path before the tragedy of Covid struck. I was able to have a clear mind for what was to come.

Aguilar says this is the first work he has been able to explain verbally: “for a long time I found it difficult to translate, or explain my work into words. Believe it or not, until this piece come along.” He was forced to engage in self-reflection when he was invited by grayDUCK Gallery director and owner Jill Schroeder to talk about El Verde for a gallery video. As the artist recalls, “I felt terrible having to turn her down because at that point I did not know what to say about the painting.” This experience made him realize that he had to learn to “articulate” his work.

On the drive home from Austin to Brownsville, the inability to talk about his work “weighed heavy on me.” During that drive, he found a way to think about the painting in verbal terms. Aguilar came to a conscious realization of something that he had always known: the knowledge that he had “always worked from my gut.” He just had to put into words that he had always worked intuitively, “always trusting my decisions as to what goes into my compositions whether it’s painting, music, assemblages or videos.”

Benito Huerta, “Exile off Main Street,” 1999, oil and jewelry on velvet, with lead panel, 84 x 132 inches, gift of Cheech Marin.

“Picasso is known for what he did and Marcel Duchamp is known for what he didn’t do.”

—Quote from an unidentified artist

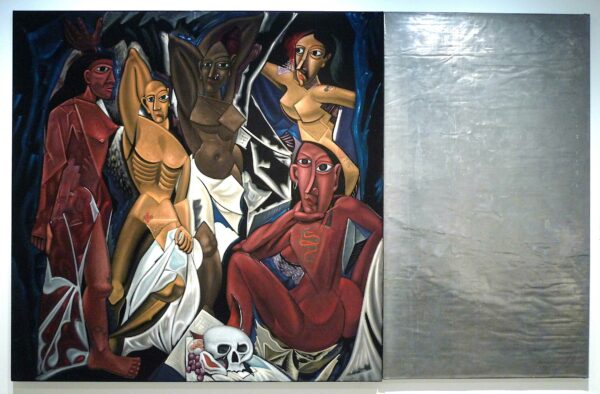

Benito Huerta views Duchamp and Picasso as the “titans” of modern and contemporary art, artists whose work resonates with the present day. His Exile off Main Street is a symbolic pairing of these two artists.

The image on the left side of this work, painted on black velvet, is a reworking of Picasso’s most famous painting, Les Demoiselles de Avignon (1907, Museum of Modern Art), which is an inaugural painting of modernism. Hal Foster deemed it “at once eccentric and crucial… a bridge between modernist and premodernist painting, a primal scene of modern primitivism. It is there that a step outside the tradition is said to coincide with a leap within it” (“The ‘Primitive’ Unconscious of Modern Art, or White Skin, Black Masks,” October #34 (Autumn) 1985.

The painting’s five figures are usually interpreted as prostitutes in a brothel, facing the viewer in what one art historian called a presentation scenario. Studies for the Demoiselles included a medical student with a skull and a sailor. In the context of a brothel painting, these figures link hypersexuality, disease, and death. Avignon was a street in the red light district in Barcelona, the city in which Picasso developed his Blue Period style, some of which depicted prostitutes.

Huerta’s title derives from the Rolling Stones album Exile on Main Street (1972), which was created in the south of France. Since red light districts are situated on side streets rather than main streets, Huerta utilized the word “off” rather than “on.” He views prostitutes as exiles.

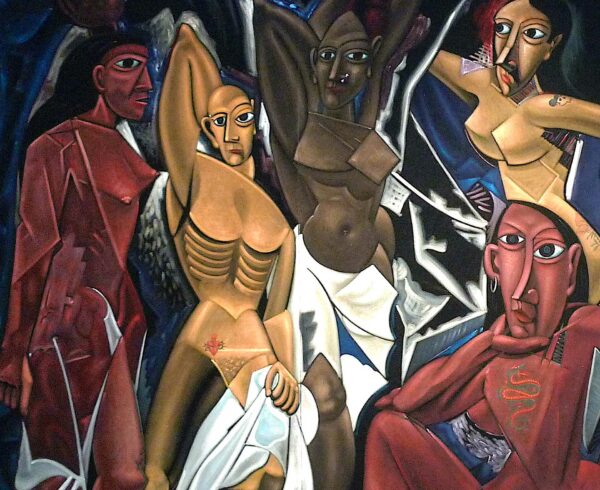

Benito Huerta, “Exile off Main Street” (detail) 1999, oil and jewelry on velvet, with lead panel, 84 x 132 inches, gift of Cheech Marin.

In his version of Picasso’s composition, Huerta “diversifies the women with different skin colorations.” In making this change, he is “subtlety referring to people of color being kept off the main street.” Huerta utilizes tattoos, actual piercings, and jewelry to depict body modifications, whereas Picasso utilized African inspired masks with scarification patterns on the heads of the two women on the right side of his painting. Huerta endows his figures with more conventional facial features.

The choice to use velvet as a painting surface stems from the artist’s experiences in Mexico. Huerta is from Corpus Christi. When he was a child, his family would cross from Brownsville into Matamoros, Mexico, where they saw velvet paintings in shops. As a graduate student in Las Cruces, New Mexico (1976-77), he went with friends to Juárez, where they saw black velvet paintings lining the streets for the delectation of tourists.

Huerta decided that velvet “would be a great surface to paint on since the fabric captures light and light reflects off the painted surface.” Additionally, he liked “the idea of using a kitschy material to create a painting.” If the Demoiselles was the ultimate highbrow modern painting in the late twentieth century, velvet was the ultimate lowbrow painting surface. Huerta decided to bring the two together.

To the right of his velvet version of the Demoiselles, Huerta added an adjoining panel covered with a sheet of lead. He did not alter the lead, beyond adhering it to the wood panel. Through this gesture, he referenced Duchamp’s Readymades (which are found, mass-produced objects that the artist designated as art objects), the artistic movement known as Minimalism, and “the idea of material as metaphor.”

The two parts of Huerta’s painting are also a pointed contrast in texture and materiality: they “counterbalance each other with the lushness of the velvet against the hard physicality of the lead.”

If Picasso’s Cubism served to negate the notion of painting as an illusionistic “window on the world,” Duchamp’s conceptual art was the final nail in the coffin of representation. Thus Huerta’s lead panel symbolically completes a project that was advanced by Cubism.

Finally, by adding a skull to the still life at the bottom of his painting, Huerta restores the emblem of death that Picasso had excised from the final version of the Demoiselles. It has been argued that Picasso’s Demoiselles is subliminally a memento mori (remembrance of death). In the most tendentious of these arguments, William Rubin claims that the references to African masks invoke death and disease. By replacing the repressed skull, Huerta’s version is explicitly a memento mori, a meaning that he thinks Picasso might have intended.

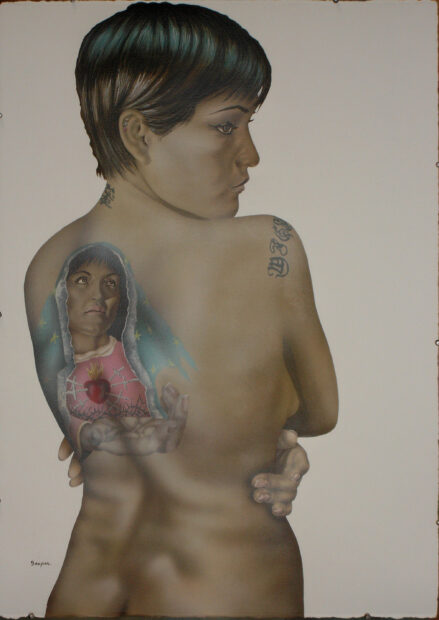

Gaspar Enriquez, “Charolito,” 2009, acrylic on paper, 41 x 29 inches, courtesy of Cheech Marin. Photograph: courtesy of Gaspar Enriquez.

Gaspar Enriquez has painted many portraits of people with tattoos. As he puts it, “people with tattoos are part of my familia of portraits.” Enriquez notes that he is “surrounded by people and family members with tattoos,” some of whom now own tattoo shops. His tattoo portraits include men who got relatively simple tattoos while they were imprisoned. On the other extreme, the tattoo artist depicted in De Puro Corazón (2020) has much of her body covered with colorful, interwoven tattoos, which were made by other accomplished tattoo artists.

Charolito is a special case, because it is the first — and to date the only — instance in which Enriquez invented a tattoo and placed it on a model’s body. A charolito is a dark and shiny patent leather shoe. As a consequence of her shiny spirit, this young woman was given this nickname by her father as a term of endearment, But her spirit was diminished by her very religious mother, who took offense at Charolito’s art.

Enriquez recalls that Charolito’s drawings, paintings, imagination, and creativity “were comparable to Salvador Dali’s.” Because they contained images of demons and sexual content, her mother called her drawings “the work of the devil,” and she tore them up. Charolito’s spirit was broken. She stopped making art and chose another career.

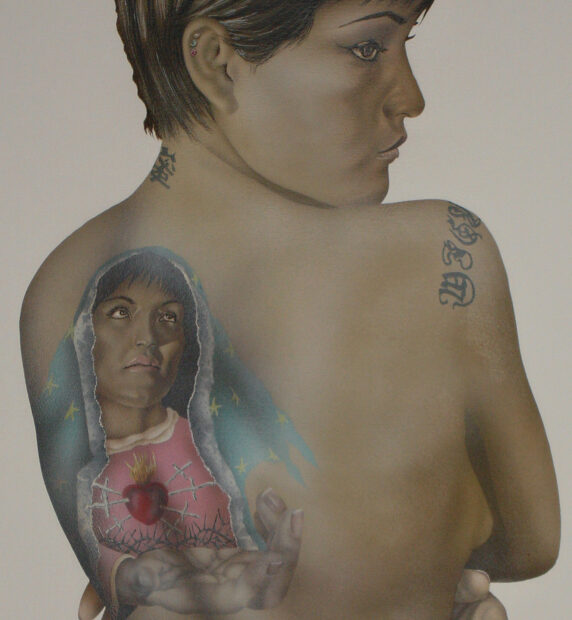

Gaspar Enriquez, “Charolito” (detail), 2009, acrylic on paper, 41 x 29 inches, courtesy of Cheech Marin. Photograph: courtesy of Gaspar Enriquez.

Given this family history, when Enriquez did her portrait, he painted a Virgin Mary on her back. He chose a sad virgin, the Virgin of Sorrows, which features a heart pierced by seven swords, above a partial view of a crown of thorns. By adding this imaginary element, Enriquez countered her mother’s theory “that Charolito was evil and her art was the work of the devil.”

With her upward directed eyes, the virgin appears to look on Charlolito with sympathy, while she extends a helping hand. This dark virgin also bears a considerable resemblance to Charolito.

For Enriquez, Charolito is a prime example of how negative criticism can destroy “a child’s spirit, imagination and creativity.”

“I’m still trying to get her to pick up her talent, imagination and creativity and run with it,” says Enriquez, “she hasn’t yet, but I won’t give up on her.”

A number of other Texas-connected artists are featured in Cheech Collects. Jari “WERC” Alvarez, who was born in Juárez and raised in El Paso (he now lives in Brooklyn). Carlos Donjuán was born in San Luis Potosi and now lives in Dallas. Jacinto Guevara, born in Los Angeles, resides in San Antonio. Born in Corpus Christi, Jimmy Peña lives and works in that city. Joe Peña was born in Laredo and lives in Corpus Christi. Marta Sánchez, born in San Antonio, lives in Philadelphia.

California Artists in Cheech Collects

Two of Glugio “Gronk” Nicandro’s best and most ambitious paintings were standout works in both Chicano Visions and Cheech Collects.

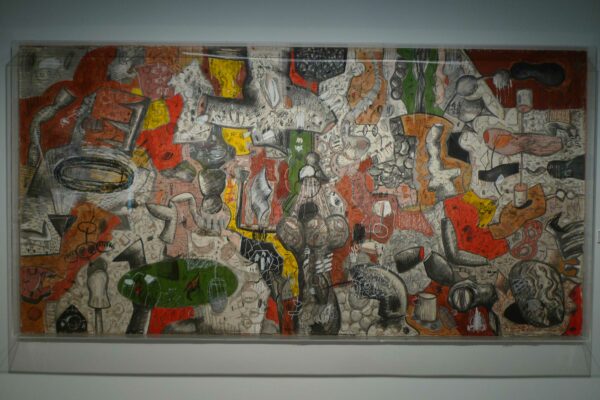

Glugio “Gronk” Nicandro, “La Tormenta Returns,” 1998, acrylic on wood panels, 144 x 96 inches, gift of Cheech Marin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

In my Voices of Art review, I referred to Gronk’s La Tormenta Returns (1998) as a

painting with unparalleled depth and complexity. His characteristic black and white compartments appear to have been invaded and reworked by multiple hands, resulting in a densely interwoven palimpsest whose imagery and style reflect diverse sources, from Brancusi sculptures to graffiti-inflected Neo-expressionist painters.

La Tormenta Returns is the product of a performance. It was created “live,” in front of an audience. The performers included a string quartet, a soprano (the eponymous Tormenta) and Gronk with an amplified paintbrush, which he utilized as a conductor’s baton. The performance lasted 45 minutes, and when it was concluded, says Gronk, “the audience saw a painting emerge from a blank wall 12-by-8-feet.” He subsequently took the painting to his studio and reworked it somewhat.

Gronk relates Tormenta Returns to film language: “it’s the moment of a dissolve from one scene to the next, it’s transition in slow motion.” The double images do not quite fit together. He emphasizes: “the melodrama is also present [in] the opera being sung by Tormenta, the central figure in the painting.” Gronk notes his experience working with people like Peter Sellars, and points out that theatrical and operatic qualities “spill into the painting.”

Glugio “Gronk” Nicandro, “Pérdida (ACCENT ON THE e),” 2000, mixed media on handmade paper mounted on wood, 60 x 118 inches, courtesy of Cheech Marin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Pérdida is likewise densely worked with a great variety of forms. Many of them recall sculptures (including a collapsed Brancusi Endless Column). The artist refers to them as shapes that take the place of people.

Pérdida (Lost) is the title of a Mexican melodramatic film from 1950 that treats a woman who was raped by her stepfather and abused by a string of men. Her current relationship with a bullfighter is threatened by her past (the title refers to lost virtue). Gronk provided me with this account of the painting:

I wanted to create it in color including the melodrama…. using shapes and forms instead of characters. Prostitution is never mentioned in the film, nor in my painting. Film has always been part of my language in painting. Not to copy it but to chew it up and see the results in painting.

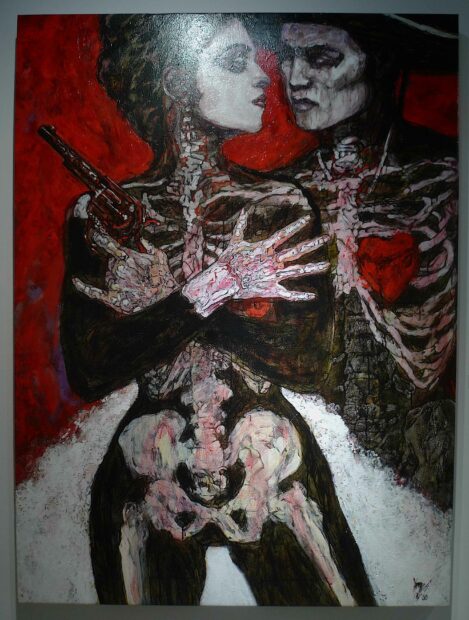

George Yepes, “La Pistola y el Corazón,” 2000, oil on canvas, gift of Cheech Marin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

George Yepes is represented in the exhibition by three paintings he made in L.A., before he moved to San Antonio and Austin. Yepes currently resides in Las Vegas, Nevada.

His La Pistola y el Corazón is a signature work. The original (owned by Sean Penn) was destroyed in a fire. Marin also owns a hand-painted serigraph from 1989 that was exhibited in Chicano Visions. This version (along with two other paintings) was made on a large scale just in time for Chicano Visions.

With the larger scale (and the oil paint medium), Yepes was able to add considerably more detail in La Pistola y el Corazón, particularly in the skeletal features. In the earlier version, the two figures appeared to be more united because they were cloaked in darkness. In the larger version, the figures are more elongated and more discrete. The woman is in full profile, and she seems to be more aloof.

Carlos Almaraz, “Sunset Crash,” 1982, oil on canvas, 35 x 43 inches, gift of Cheech Marin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Sunset Crash is a fine example of the motif that is most prized by Carlos Almaraz’s collectors. It arguably reflects the apocalyptic characteristics of the artist’s late period, which was haunted by the AIDS crisis. In this bi-level crash, a multi-vehicle collision has caused debris — and at least one flaming car — to fall from the upper level ramp, imperiling cars that whiz by on the lower ramp. This devastation has the potential to cause considerably more ruin and bodily injury: unseen cars on both ramps could crash into the flaming cars depicted in this scene. This wholesale destruction is at odds with the beautiful colors of the landscape, which function like a rainbow behind a scene of violence.

Almaraz’s use of color and his painterly style was enormously influential on California artists. He was also a major influence on the San Antonio-based artist Adan Hernandez, as I note in the article cited above.

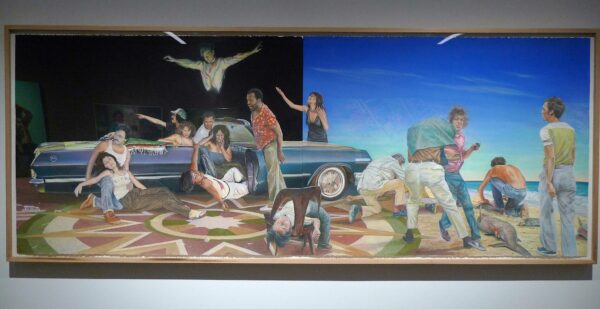

John Valadez, “Getting Them Out of the Car,” 1984, pastel on paper, 37 ½ x 100 inches, gift of Cheech Marin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

As I noted in my VOA review, John Valadez’s pastel “endows quotidian urban violence with the aura and pathos of both religious and political martyrdom.” The big convertible evokes the limousine in which John F. Kennedy was assassinated, an association amplified by the two pointing figures, which also evoke photographs taken immediately after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination.

A young man in white spills out of the open door, while two figures on the left enact the pose of the pieta. One young man must already be dead (presumably the one in the center foreground), since he is transfigured above the car in the pose of a crucifixion.

Inexplicably, this drive-by shooting seems to take place not on the street, but in a public building with an elaborate compass-patterned marble mosaic (such as a train station). On the far right, the scene shifts from night to day, and we are transported to a fishing scene on the beach, where a shirtless man is cleaning the dead fish that lie on the sand. Analogously, the human corpses will be cleaned for their funerals. For reasons that are not apparent to us, a man in white pants is struggling with a woman. He has his left foot on the marble mosaic and his right foot on the beach.

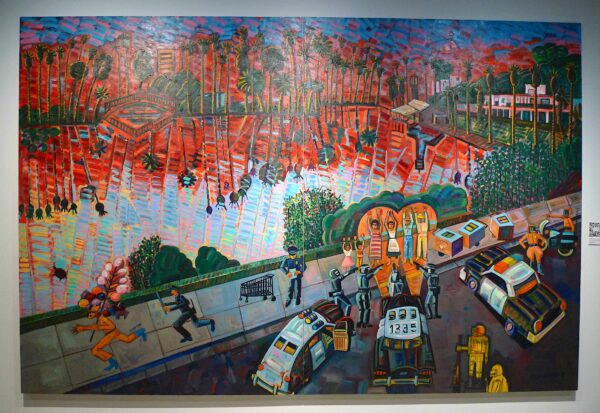

Frank Romero, “The Arrest of the Paleteros,” 1996, oil on canvas, 96 x 144 inches, gift of Cheech Marin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Marin avidly collected Frank Romero’s work. His Arrest of the Palateros didn’t make much of an impression on me in Chicano Visions, which included many other works by the artist, including the monumental (120 by 288 inch) ¡Mejico, Mexico!, which was so large that it took up most of SAMA’s capacious lobby.

Arrest of the Palateros has a very prominent placement in Cheech Collects, which is so bereft of explicitly political paintings that it really stands out in this exhibition. Romero’s works have a very playful quality, even The Death of Rubén Salazar (1986). The tone of this image of police harassing vendors is more comic than tragic, even though the police have drawn guns, full riot gear, and they outnumber the paleteros.

Frank Romero, “The Arrest of the Paleteros” (detail) 1996, oil on canvas, 96 x 144 inches, gift of Cheech Marin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

I particularly like that the headlights of the police car in the lower right seem to form a valentine-like heart.

Eloy Torrez, “It’s a Brown World After All” [portrait of Cheech Marin, detail], 2006, oil on canvas, 60 x 60 inches, gift of Cheech Marin. Photograph: courtesy of the artist.

When he was a child, the artist imagined himself as a time traveler. As an adult, he enthusiastically embraced his ancestry, both indigenous and European. “If we could time travel and see all that,” says Torrez, “it would be amazing.” He describes life as “a magical mystery tour.” In his art, he wants to encourage people to see more than the merely visible.

It’s a Brown World After All was not a commissioned work. “I did it because I wanted to do it,” says Torrez. He decided to paint a portrait of Marin wearing the same crown that Siguenza wore. I asked for an explanation of the symbolism of the birds and the sea, and Torrez gave me this response:

Regarding the birds, I asked my subconscious and got no reply. [It is] probably referencing something from my childhood, a fascination observing crows/ravens when visiting the small pueblito of Punta De Agua [New Mexico] where my grandparents on my father’s side lived. Putting ravens would have been interesting, but the seagulls are more representative of Cheech’s surroundings in Malibu.

When it came time to give the painting a title, Torrez reflected on popular culture, Marin’s celebrity status, his brown skin, and the preponderance of brown-skinned people in the world.

It’s a Brown World After All references the Disney ride It’s a Small World after All. The latter features a voyage through all seven continents, accompanied by a chorus of animatronic children from around the world. It has been one of Disney’s most popular attractions since it was created for the New York World’s Fair in 1964-65 to benefit UNICEF.

Torrez notes that Marin is so famous that even children recognize him. The title he gave to the painting helped the artist to “connect all the dots.”

It’s a Brown World After All pays tribute to one of the most eminent brown personages in this country while underscoring that we are living in a brown world — one that grows browner by the day. “The number of brown people is so huge, and we are still called a ‘minority,’” concludes Torrez.

Judithe Hernández, “Juárez Quinceañera,” 2017, pastel mixed media on canvas, purchased through the Wingate Foundation Acquisition Fund with support from 11 other donors. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Hundreds of young women have been murdered in Juarez, Mexico, since 1993. The majority of them have been maquiladora (factory) workers. Judithe Hernández was long unaware of this series of unsolved murders “occurring literally at our doorstep.” She began her Juarez series in 2007 “in an effort to raise awareness about this tragedy.”

According to an artist’s statement, Hernández sensed “cultural and historical parallels between the murdered women of Juarez and the sacrificial victims of the ancient Pre-Columbian ball game.” All of these victims, she says, “were young, all were without social or political influence, and all were the price society was willing to pay to protect the status quo.”

Historically, young people in particular were not sacrificed at Pre-Columbian ballgames. These victims, usually thought to have been elite male captives or ballgame players (though there is much uncertainty about the process), were decapitated. Additionally, there is a question about whether the sacrifices were real, or whether sacrifices depicted in relief carvings were allusions to sacrifices in myths. See Live Science: Children were sacrificed to the goggle-eyed rain god, which the Aztecs called Tlaloc. Moreover, in an attempt to induce sympathetic magic, they were made to cry before they were sacrificed.

Hernández’s source for the woman’s head, jewelry, and headdress in Juárez Quinceañera, however, was not a sacrificial victim, but a statue of a woman who was deified after dying in childbirth. The Mesoamerican peoples analogized these deaths to male warriors who died in battle. Death during childbirth was likewise viewed as an exemplary, virtuous fate that conferred immortality.

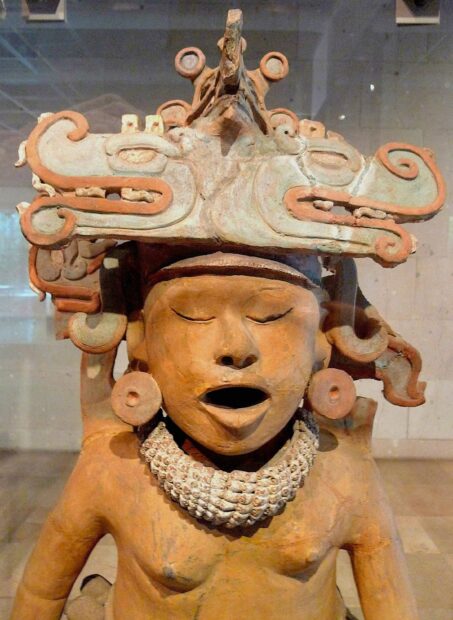

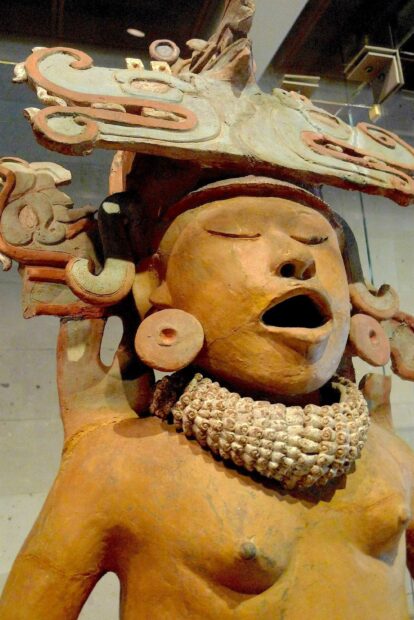

Cihuateotl ceramic sculpture from Central Veracruz (Río Blanco-Papaloapan culture, detail), c. 600-900 AD, height 1.4 meters, Xalapa Museum of Anthropology, Mexico. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

The above photograph is one of many life-sized ceramic sculptures from Mexico’s Gulf Coast region. According to Rubén Morante López, this woman “wears a necklace of shells forming a bicephalous [double-headed] blue serpent and a tangle with parallel stripes tied to a bundle of shells, and over this, a blue cord knotted at the front.” Her open mouth and closed eyes symbolize her death, which “not only deified her but also gave her the right to accompany the Sun, which may be represented by the red circle painted on the woman’s skirt” (From Xalapa Museum of Anthropology – a Guided Tour, Gobierno del Estado de Veracruz/Universidad Veracruzana, Xalapa, 2004, p. 146).

Cihuateotl ceramic sculpture from Central Veracruz (Río Blanco-Papaloapan culture, detail), c. 600-900 AD, height 1.4 meters, Xalapa Museum of Anthropology, Mexico. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

A quinceañera is a festive occasion, when a fifteen-year-old young woman has a coming out party. But in Juarez Quinceañera, the young woman has a face that signifies death, and she wears a black dress appropriate for mourning rather than celebration. The bloody handprints on the pink wall add an additional grisly note.

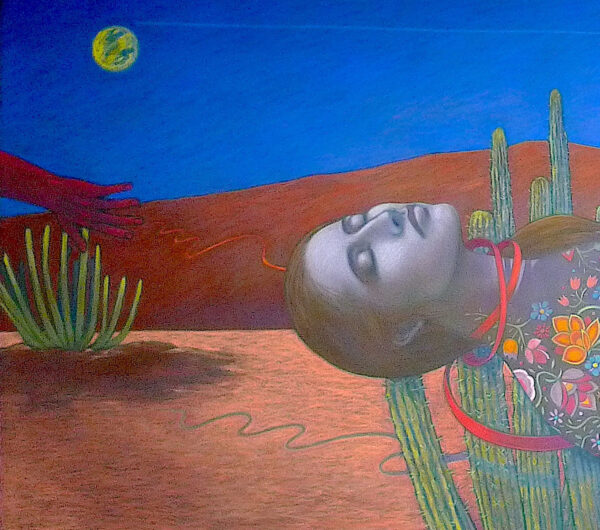

Judithe Hernández, “Santa Desconocida,” 2016, pastel on paper, 30 x 88 inches, purchase through the Wingate Foundation Acquisition Fund with support from 11 other donors.

Judithe Hernández, “Santa Desconocida,” 2016, pastel on paper, 30 x 88 inches, purchase through the Wingate Foundation Acquisition Fund with support from 11 other donors.

Hernández’s beautiful and haunting Santa Desconocida (Saint Unknown) seems to float unconsciously above a cactus plant, as if she were in a deadly dream.

I wonder whether her placement adjacent to the cactus was an allusion to Francisco Goya’s Disasters of War prints, which depict bodies on trees, or to Symbolist or Surrealist artworks that have similar imagery. Or could this be an allusion to Aztec sacrifice, as noted above in my discussion of César Martínez’s Hombre Que le Gustan las Mujeres?

Moreover, is the red ribbon that wraps around her neck an allusion to Frida Kahlo, or to blood circulation and/or the fatal lack thereof? Does her pale bluish color refer to strangulation?

What is the meaning of the reddish hand in the left corner that almost seems to reach out for the red ribbon? Is it the hand of the woman’s murderer? Or is it the hand of the discoverer of her corpse, or that of a distraught mourner? Or could it be the hand of a Pre-Columbian sacrificial victim, highlighting the parallel Hernández is making in this series?

A rabbit is depicted in the moon in the upper left. The Mesoamerican peoples imagined a rabbit on the moon rather than a man in the moon. In this particular work, it is presumably a sign pointing to parallels between the Juarez femicides and ancient Mesoamerican human sacrifice. Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec patron deity, slew his sister Coyolxauhqui, who became the moon. According to the artist’s statement, “the series has become a visual metaphor for the violent deaths of hundreds of young women in Ciudad Juarez.”

Unfortunately, my questions to the artist on this piece went unanswered, so I can’t say much with certainty about her intentions and the significance of particular elements. Art is rarely self-explanatory. This lack of interpretational certainty underscores the need for explanatory texts at the Cheech.

Ana Teresa Fernández, “To Press I” and “To Press II,” 2007, oil on canvas, gift of Cheech Marin. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Ana Teresa Fernández refers to her work as Magical Non-fiction. She explains it this way on her website: “Where unimaginable conditions are the reality, I seek to portray dreamscapes of what’s possible. The courage to transform is up to us.” Born in Mexico, Fernández has been keenly aware of the virgin/whore and clean/dirty dichotomies since childhood, and she addresses them in her performances.

To Press 1 & 2 are derived from a performance called To Press from 2006. They are part of a larger body of work called Pressing Matters. As she notes on her website, her first paintings in this series “were of women dressed in Tango attire, performing cleaning activities or domestic chores in private and public spaces.”

At the time Fernández performed To Press, she was working on her MFA at the San Francisco Art Institute. Her friend and colleague, the photographer Cristina Piza, was a Fullbright student from Costa Rica. Piza lived in a pre-WWII apartment building that had small, efficient domestic spaces designed for women. The ironing board that was built into the wall fascinated Fernández. As she recalls:

I had begun doing these dance/ tango performances in my own apartment doing domestic labor. I asked if she [Piza] would photograph me as I danced/explored/performed with her ironing board. She agreed to it. I came over, we had a beer, and I began to move. You can see the beer in the painting on the shelf…. The ironing board in Mexico is a “burro.” The work animal. I wanted the space to talk and dance with me. I infused the energy of a (tango) partner into this domestic space, often a place where women spend all day, alone. And it spoke back/danced incredibly. I straddled it in various ways and thus a new energy and conversation arose.

Piza said she was never able to see her ironing board/kitchen the same way.

Fernández explains that in her performances, the photographer “is always the third tango partner.” In this instance, “Piza was also dancing with me as she moved and photographed me.” These works are spontaneous: “I never know what any of my movements look like until I am done.” Fernández regards light as a fourth participant: “The light coming into the apartment was another active ingredient or participant in the mix.”

Fernández is open to accidental effects. Literally.

When I bumped into the top part of the ironing board, which is for the sleeves, it slammed down on my behind. I vaguely remember Piza encouraging me to not fix it and keep going. When I saw the photograph of the board almost penetrating the light of the window, I knew I had found the image to make a painting. It was so provocative. It felt like a threesome, of the ironing board, the light and myself. The viewer can see very small openings of light between my body and the ironing board, the chord is also coming out from behind me. These details I believe are what adds to the sensuality and participation of exterior factors.

Fernández met Marin in 2012 or 2013. She recalls speaking briefly with him about her work. She gives this explanation of the appeal of her work:

I just know he really fell in love with these when he saw them. I think part of what draws him to my work is that essence of “oh fuck, is that real or am I imagining it?” portrayal of my work, where you are questioning what you are looking at. Is this for real or am I high?

Cheech Collects Compared to Chicano Visions and Assessment of the Collection

Chicano Visions, which opened at the San Antonio Museum of Art on December 15, 2001, featured 80 paintings and pastels by 26 artists, dating from1969 to 2001. Of these works, 55 were lent by Marin. Judging by the high proportion of important works that were of recent vintage, Marin undertook a major buying spree to upgrade his collection prior to the opening of the show. His emergence as a major collector, then, may date to around 2000.

In addition, another 25 choice works were borrowed from private collectors. As I noted in my VOA review, these loans were made “to provide a broader view of Chicano painting.” Chicano Visions concentrated on southern California (especially L.A.) and south Texas (especially San Antonio).

Cheech Collects, which opened on June 18, 2022 and ran through May 14, 2023, featured just under a hundred works by 44 artists. Thus it is a larger show by about 20 works, and it had about 18 more artists. But in terms of highlights, Chicano Visions was a vastly superior show because it had large concentrations of choice works by some of the best artists. These included loans of two additional car crash paintings by Almaraz and some very fine works by John Valadez (some lent by the late Dennis Hopper). See the catalog Chicano Visions: American Painters of the Verge (Bullfinch, 2002).

More significantly, Chicano Visions benefited from the loan of some critically important political paintings, which served to rectify a great weakness of Marin’s collection. These included arguably the three most important paintings from Mel Casas’ Humanscape series: Humanscape 62: Brownies of the Southwest (1970), Humanscape 63: Show of Hands (1970), and Humanscape 68: Kitchen Spanish (1973). The loan of four paintings by Carmen Lomas Garza included Heaven and Hell (1991), which shows a dance scene on the top level and a subterranean vision of people in fatigues chained in hell. Jesse Treviño’s Los Piscadores (1985), which was also loaned to Chicano Visions, featured workers laboring in a cotton field. (Casas, Lomas Garza, and Treviño were among many talented artists that were in the Con Safo art group.) Loans to this exhibition also included two political works by San Francisco Bay-area artist Rupert García.

In a videotaped lecture at Purdue University during the run of Chicano Visions, titled “Cheech Marin: An Interpretation of a Culture Through Chicano Art,” Marin discusses Casas’ Show of Hands (at 20:10), followed by three of Lomas Garza’s paintings that were shown in San Antonio (Una Tarde, Quinceanera, and Earache Treatment Closeup), as well as Treviño’s Los Piscadores (at 29:22). Clearly, Marin values these works highly, since he chose to speak about them rather than works he himself owned. Nonetheless, he did not purchase these major paintings from Casas or Lomas Garza that were on offer, nor did he buy a comparable painting by Treviño (Los Piscadores is owned by its commissioner, who is depicted in the painting). My assumption is that the relatively high prices of these works served as a barrier to their acquisition. On the other side of the price spectrum, several artists told me that Marin has been a lifeline to them in times of need.

In my opinion, Cheech Collects looks too much like Chicano Visions. The criticism I applied to the latter in my 2002 VOA review is relevant to the former:

What can we really learn about the Chicano experience from Chicano Visions? Not enough. A viewer completely ignorant of Chicano culture could attend Chicano Visions, savor many aesthetic delights, and depart the museum without learning much about Chicano culture. This art is a response to particular historical circumstances that warrant explanation on the walls of the museum. I would have liked to have seen more politically explicit work that addresses historical oppression and disempowerment. After all, why did “Mexican Americans” choose to become Chicanos?

Museums are tax-exempt because they are educational institutions. Because both exhibitions had a paucity of texts, they failed to do much educating. A good first step would be to have an introductory gallery that explains the Chicano experience through art. Cheech Collects has so few explicitly political works that it could not adequately perform this function, had it made that attempt. Loans or additional acquisitions could serve to bridge this gap. Marin is actively collecting photographs and prints, which will make it easier to narrate the Chicano experience.

Chicano Visions and Cheech Collects have similar strengths and weaknesses. Most of the largest, most ambitious works are by male artists. The L.A.-based group known as Los Four is very well represented, especially Carlos Almaraz (Marin’s favorite artist) and Frank Romero. Marin has excellent work by Gilbert “Magu” Luján, and now the museum has two excellent works (discussed above) by the group’s fifth member, Judithe Hernández. Gronk and Patssi Valdez, two members of the L.A.-based group ASCO are well-represented in Marin’s collection. Several additional works by these two artists were exhibited in Chicano Visions. (I hope the collection obtains photographs by Valdez, because I prefer them to her paintings.) Ideally, the Cheech should adequately represent other major groups, including those outside of L.A. and outside of California.

Marin also has a large collection of works by the L.A. artist Margaret Garcia, who works in a painterly style and uses colors similar to those of Almaraz. In general, he seems to have a preference for colorful, loosely painted works.

The most impressive body of work in Marin’s collection, however, might be by John Valadez, whose Surrealist-inflected realist technique, whether in paint or pastel, is astonishing.

The greatest weakness of Cheech Collects is the same one I noted in my 2002 review of Chicano Visions:

… the representation of female artists is one of the most serious weaknesses of the show. One problem is that several Chicanas are not represented by their best work. The exclusion of so many major Chicana artists constitutes a deeper flaw. Works by artists such as Juana Alicia, Judith Baca, Yreina Cérvantez, Eva Garcia, and Yolanda Lopez (just to name a few) [I limited this discussion to painters and pastel artists, which was the focus of this exhibition] would have added important dimensions to the show (mural scale work, critical explorations of gender and religion, etc.).

Marin does not appear to have much of a taste for political works in general, and feminist works in particular. After we add the mediums of print, photography, sculpture, and installation, as well as the many artists who have emerged since 2001, there are a great many Chicana artists that can be added to the above list.

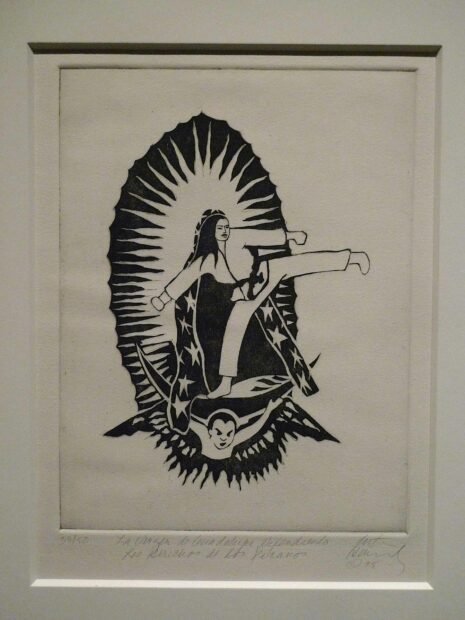

Ester Hernandez, “La Virgen de Guadalupe Defendiendo los Derechos de los Chicanos” (The Virgin of Guadalupe Defending the Rights of Chicanos), 1975, etching and aquatint, 19 x 15 inches, collection of the artist. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

On the same trip to California that I visited the Cheech Center, the Getty Museum displayed Ester Hernandez’s La Virgen de Guadalupe Defendiendo los Derechos de los Chicanos in its Visualizing the Virgin Mary exhibition. It is a work that really packs a punch. When I saw it at the Getty, I imagined how great it would look at the Cheech, where it would also add a very important political dimension.

By noting the need for more politically explicit art, I am not denying that the other works on view at the Cheech have social and political meanings. One reason I have discussed some of these works in detail is to explore some of these significations, which are not generally self-evident.

As I noted in my review of Chicano Visions:

Many of the weaknesses of this exhibition are a predictable consequence of its genesis out of a single private collection (regardless of how well-intentioned and discerning the patron).

Whereas most private collectors are eager to obtain additional works by their favorite artists, curators who build up museum collections and who put together representative exhibitions seek to identify the key innovators and their most important works, especially those that have appeared in landmark exhibitions. While Marin has broadened his collection significantly since I saw it in 2001, I do not see much evidence in Cheech Collects that he has added important works by the key innovators of Chicano art.

A number of major museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, are actively collecting Chicano art. In the future these museums will no doubt have a good number of stellar works in their collections. If the Cheech Center wants to be notable a decades from now, it should acquire more of the best and most important Chicano artworks, in addition to broadening its collection in general.

The choicest and rarest historical works will not always be available. Mel Casas, for instance, made six Humanscape paintings with explicit Chicano themes between July of 1970 and November of 1974. For a Chicano art museum, these are the most desirable paintings in his oeuvre. Two had long been in the collection of the late Jim Harithas, who told me they would be left to Texas museums. Brownies of the Southwest was purchased by the Smithsonian in 2012, and Humanscape #70 (Comic Whitewash) was bought by the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art this year.

Additionally, some marvelous works are absolutely unique, and would serve as destination pieces to draw visitors to the center, such as Gaspar Enriquez’s only large-scale installation, La Rosa Dolorosa de Mi Vida Loca (1995). (I wrote about it in his retrospective catalog, Gaspar Enriquez: Metaphors of the Barrio, El Paso Museum of Art, 2014).

In the video noted above, Charles Shepherd III, who introduced Marin, called his collection “the largest in the world, and the finest in quality, his competitor Joe Diaz even says that.”

Since 2001, most reviews and discussions of Marin’s collection that I have seen have used these superlatives, so I presume that these terms were used in publicity with the collector’s approval.

Marin’s collection is objectively not the largest, which was built by Gilberto Cárdenas. He and his wife Dolores García recently donated 5,650 works to the Blanton Museum at the University of Texas at Austin. Additional works have been added to this gift, which is partially a purchase. Other benefactions from the Cárdenas collection include over 2,200 works to The National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago, an earlier gift of 428 works to the Blanton, and gifts to the Snite Museum of the University of Notre Dame and the Smithsonian Museum of American Art. The bulk of the Cárdenas collection is made up of works on paper, primarily prints.

Diaz informed me that he never told anyone that he thought Marin has a better collection. I have seen three exhibitions of the Diaz collection and two of the Marin collection, and from what I have been able to observe, the Diaz collection has a higher overall quality. A number of Marin’s works are of middling quality, and a few are absolutely terrible. Both collectors have large concentrations of works by their favorite artists. Neither collector favors political works, and neither has attempted to build an encyclopedic collection. As a collector, Diaz favors draftsmanship rather than expressive, painterly qualities.

I wouldn’t declare that either collection was the better of the two without seeing both of them in their entirety. In any case, Marin’s collection is certainly one of the biggest and one of the best collections of Chicano art in the world.

Additionally, the AltaMed Art Collection, an L.A.-based corporate collection of more than 2,000 pieces (not all of which are Chicano art), is building an exhibition space in its storage facility. The word on the street is that AltaMed has high ambitions for its collection of Chicano art. A great deal of Chicano art is currently being collected and made accessible to the public, which is a very positive development.

In the interest of disclosure, I wrote the catalog for the exhibition of selections from Diaz’s collection in 2004 (it is cited above). I have also borrowed works from the Diaz and Cárdenas collections for exhibitions I have curated, most recently for The Day of the Dead in Art at Centro de Artes in San Antonio.

The Creation of the Cheech

The City of Riverside, which was planning a glitzy new main library building (it opened in 2021), needed to find a use for its old landmark building. The Riverside Art Museum (RAM), which had just opened a very successful exhibition of works on paper borrowed from Marin, partnered with the city to make a bold proposal in 2017. In return for Marin’s collection, the city offered the library building, and RAM undertook responsibility to raise funds to cover the costs of renovations. Marin quickly agreed, and he leveraged his celebrity to assist in raising money for the project.

Ever since the exhibition Chicano Visions opened in 2001, Marin has been the most visible public advocate for Chicano art. Moreover, the announcement of the agreement with Riverside in 2017 greatly enhanced his renown as a collector. In the fall of that year, Marin was selected as one of ARTnews magazine’s Top 200 Collectors in the world. It is a title he maintains.

The ARTnews listing was heavy with bluebloods and billionaires when it first appeared in 1990. It has become more diverse in terms of collecting interests in the U.S. (it always covered African, Asian, and Latin American art). Maximilíano Durón, a senior editor at ARTnews, has worked on the list since 2014. He gave me this statement about the evolution of the list:

ARTnews, like everything else in the mainstream art world, has had its blind spots, and collectors of color were not highlighted on the list as much as they should have been. Over the past 10 editions, ARTnews has worked incredibly hard to diversify the list to better reflect the reality of the art world and the art market, and to show how collectors of color have long been influential, if only recently recognized. Raymond J. McGuire [a collector of Black artists] and Cheech Marin, for example, both have collecting practices that extend decades beyond their first appearance on the Top 200 list. Our 2022 edition is our most diverse one to date. As I wrote in my introduction to the list, it is important to mark this to show the progress that has been made and how much work in the art world still remains to be done.

Through his inclusion on the list, Marin has gained entrée to an informal, exclusive club whose members not infrequently spend tens of millions of dollars for a single work, and sometimes more than $100 million. What some of these high rollers pay for a single painting or sculpture could buy all of the Chicano art in all of the museums in the world. Nonetheless, Marin now has what many of them do not — a namesake museum. As of 2015, only 46 of the Top 200 had their own museum or public exhibition space (“Inside the 2015 List,” ARTnews, July 7, 2015).

RAM began a fundraising initiative in 2017, and a pledge of $600,000 from Altura Credit Union enabled it to meet its first benchmark of $3 million in 2018. The state of California provided $9.7 million to RAM in its 2018-19 budget, which accounted for more than two-thirds of the $13.3 million that was ultimately needed for renovations. Another large pledge came from Bank of America, which came up with $750,000 in 2019. Additionally, $1.2 million was raised to cover incidental costs. The Cheech Center is administered and programmed by RAM, a nonprofit entity that is not part of the city government.

In January of 2021, the Riverside City Council entered into a 25-year contract to support the museum, in an amount averaging a little over $1 million per year for the first decade (with an expected $3 million to be returned to the city from ticket sales). The balance of the 15 years of the contract will be renegotiated after ten years, as noted by the Press-Enterprise.

The Cheech is a 61,420-square-foot facility with two floors of galleries and a basement. Moise, Harbach & Hewlitt, a local firm, designed the building, which opened in 1964, replacing the 1903 Mission-style Carnegie Library. For multiple photographs of these buildings and a history of their creation, see Glenn Wenzel, “From Carnegie to mid-century modern to The Cheech: A history of Riverside’s downtown library,” The Raincross Gazette, June 20, 2022).

The 1964 building is in the New Formalist style, which is modernist, though inspired by classical architecture. Its stark brick façade is adorned with eight diamond-patterned concrete screens. Each one weighs 17 tons. The point of each diamond terminates in a stylized dove. For a detail, see Heather David’s photograph on flickr.

These doves express a hope for peace during one of the hottest periods of the Cold War. President John F. Kennedy had sent Green Berets and helicopters to Vietnam in May of 1961; in October of that year, the bond was passed that funded the library. The Cuban Missile Crisis had threatened nuclear war in October of 1962; ground was broken for the library in June of 1963. Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964, the year the library was completed. It was dedicated in March of 1965, the same month that President Lyndon B. Johnson sent regular combat troops to Vietnam and launched large-scale bombing attacks that lasted for several years.