Collidoscope: de la Torre Brothers Retro-Perspective, the first temporary exhibition at The Cheech, is such a dazzling and astonishing show that it will not be easy for the museum to surpass it. Einar (b. 1963) and Jamex (b. 1960) de la Torre, sculptors born and raised in Guadalajara, moved with their family to California in 1972. Currently, they migrate between studios they maintain in San Diego and Enseñada, Baja California, Mexico, so they experience both cultures from the inside and from the outside on a continuous basis. The brothers also travel around the world, where they sometimes work at glass studios. They produce works steeped in their particular cultural experiences that humorously and critically comment on art, history, religion, politics, consumerism, and various aspects of material culture, including Mexican and U.S. popular traditions and pre-Columbian monuments.

Collidoscope, which features over 70 works produced during the 30-year collaboration between the de la Torre brothers, was guest curated by Selene Preciado of the Getty Center. It will travel (in somewhat reduced form) through 2025, with its first stops happening now at The Art Museum of South Texas in Corpus Christi, and then it will be on to the University of Texas at El Paso (see the complete schedule at the end of this article).

The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture of the Riverside Art Museum, which is housed in the landmark building that was formerly the city library, opened in June of 2022 to widespread acclaim. It instantly became the world’s preeminent exhibition venue dedicated exclusively to Chicano art.

The exhibition’s title is a homonym for kaleidoscope. But picture a collide-oscope, with the emphasis on cultural collisions, rather than merely beautiful colored refractions, though much of the work produced by the de la Torre brothers also has kaleidoscopic qualities. (The show’s title has nothing to do with the Callidoscope, the interactive musical instrument invented in 2015.) Through a “collision of imagery, themes, and references,” says guest curator Preciado, the two artists “unpack the tensions and contradictions of our postcolonial transcultural identity.”

The brothers were educated at California State University at Long Beach, where they learned glass blowing techniques, among other skills. Glass, however, is only one element in their work (most of their pieces, including their most ambitious ones, are mixed media), and they prefer to be called sculptors rather than glass artists. Nonetheless, they appreciate the unique properties of glass. As Einar noted in a talk on the Collidoscope exhibition:

It’s also fair to ask us, “Why bother with hot glass as a sculpting medium, if we are sculptors?” And the answer for that is that glass is simply the most spontaneous medium in sculpture. In two days you have a sculpture that is completely polished, in full color, with all these coloring techniques (De la Torre Brothers: Collidoscope: A Retro-Perspective, Penny Stamps Speaker Series, University of Michigan, 2022; hereafter referenced as DTBC).

“Blown Glass is such a pleasure,” remarks Jumex in the DTBC video. To see the brothers fabricate a single glass piece, beginning with the head, see Delft Blue Teapot by De la Torre Brothers, which was made at the Glasblazerij in Leerdam, the Netherlands in 2017.

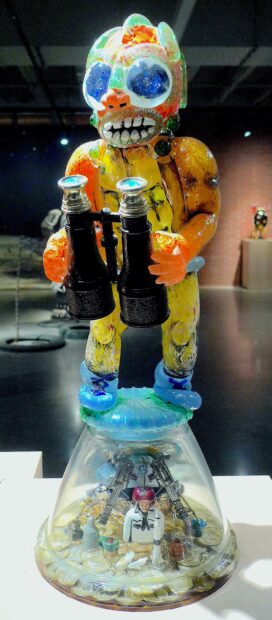

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “El Drugstronauta,” 2012, blown glass and mixed media, courtesy of the artists and Kopin Del Rio Gallery. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The top portion of El Drugstronauta is blown glass, except for the binoculars, which are fashioned out of an Avon perfume bottle in the shape of binoculars. I had assumed this figure was a drug cartel lookout, and that the space imagery in the base below it was ironic. In my initial reading, the drug smuggling lookout (the glass statue) has the appearance of a stargazer, someone interested in outer space rather than the gaps in the border wall, or the movements of U.S. border patrol officials.

Einar, however, explained to me that the brothers conceived the sculpture with other ideas in mind, though they create multivalent works that permit “many possible readings.” (They sometimes offer different explanations of their own works.) The brothers noted that numerous pharmacies in Mexican border towns offered low prices and “more accessible drugs,” which attracted customers from the U.S.

The Drugstronauta has dilated eyes and is so high that he thinks the Avon bottle is a real pair of binoculars (and so do we observers, for that matter). Clearly, the exhibition needs more explanatory texts, which would provide much-needed direct access into the mindset of these two imaginative and wide-ranging artists.

The sculpture’s base features a miniature tableau, with assorted appropriated objects, including coins, a rocket ship, tiny high heels, and a larger space landing vehicle in the rear. The de la Torre brothers prefer to use the term “carefully selected objects” in place of “found objects,” because they utilize great care when they choose pieces for inclusion in their sculptures. The helmeted astronaut is none other than Jesús Malverde.

Jesús Malverde is a saint in popular religion (not official Catholic religion) based on a legendary figure that was a Mexican Robin Hood. Malverde, who was always popular with the poor, has a long-standing status as the patron saint of thieves and smugglers. More recently, he became a narcosantón, a patron saint of drug cartels and drug traffickers. Drug traffickers aligned themselves with Malverde to elicit popular sympathy in the last decades of the twentieth century. They also fueled the popularity of their patron saint by funding shrines dedicated to him (See Matt Levin, “Meet Jesús Malverde, the patron saint of Mexico’s drug cartels,” Chron.com, Sept. 3, 2015.)

The bell jar that forms the base of El Drugstronauta is an appropriated Ikea salad bowl. It houses a shrine like those devoted to Malverde, but on a miniature level. The brothers make frequent use of Catholic imagery, which they often combine with other religious, popular, and/or political traditions. Since the eponymous Drugstronauta is a drug user, the Malverde shrine could conceivably be a personal shrine of his own making. But it is primarily intended on a symbolic level: the space imagery refers to the high the drug user gets from his drugs.

Einar points out a “big blur with ‘legal’ and illegal drugs, as more states legalize and broaden the spectrum of acceptable recreational drug use.” As noted above, U.S. consumers have increasingly utilized Mexican pharmacies. El Drugstronauta addresses the increasing legal accessibility of drugs, and the concomitant decline of illicitness. Drugs that had once been the domain of narco-traffickers (under the protection of Jesús Malverde) are increasingly purchased legally in drug stores and dispensaries, thereby diminishing the need for Malverde’s protection and divine intervention.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Colonial Atmosphere,” 2002, mixed media installation, 140 x 360 x 450 inches, courtesy of the artists and Kopin Del Rio Gallery. Photo: Melissa Richardson Banks.

Colonial Atmosphere is the most astounding installation produced by the de la Torre brothers to date. The tiny landing craft in the base of El Drugstronauta has ballooned to full size, and it has been provided with an eminent visage. The de la Torre brothers have reproduced a monumental Olmec head as the face of their lunar landing craft.

Monumental Olmec head (with Ruben C. Cordova), La Venta Monument 1, almost 8 feet high, relocated to the Parque-Museo La Venta, Villahermosa.

The brothers have copied (in a mosaic of cast fiberglass resin) the monumental Olmec head from the site of La Venta, known as Monument 1. In their version, they have exaggerated the upturned mouth and they have greatly enlarged the eyes. In general, the bumps and hollows of their face are given more prominence, in contrast to the more flat-bottomed, boulder-like aspect of the Olmec original.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Colonial Atmosphere” (detail of Olmec head-shaped landing craft), 2002, mixed media, courtesy of the artists and Kopin Del Rio Gallery. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Ironically, the de la Torres have transformed a 24-ton sculpture of an Olmec ruler into a manned spacecraft that has landed on the moon. The Olmec (1200-400 B.C.) served as the “mother culture” of Mesoamerica: they developed some of the core belief systems, rituals, and iconographic traditions that were foundational for Mesoamerican cultures. Olmec influence spread far beyond its heartland on the Gulf Coast of Mexico. The de la Torre brothers, in turn, extend this influence all the way to the moon. Technological updates include black-and-white televisions that create the effect of blue eyes for the spacecraft’s face, as well as a helmet fashioned out of sheet glass. The craft’s landing pads are perhaps the most rasquache element: they consist of wire hubcaps that are spray-painted gold.

The significance of the randomly scattered tires puzzled me. It seemed to me as if this moonshot was part junkyard, part conquest of space. Were the brothers intimating that pollution was an inevitable consequence of space exploration, and of colonization in general?

The tires could also punningly reference the Olmecs. “Olmec” is a Nahuatl word (the language of the Aztecs) that means “rubber people” (we don’t know what language the Olmecs spoke, or how they referred to themselves). In a sense, then, the tires are as “olmec” as the big head.

Einar informed me that the tires are meant to represent the craters on the surface of the moon, a signification I had missed entirely.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Colonial Atmosphere” (detail of Coatlicue/Astronaut moon-walker saluting the flag), 2002, mixed media, courtesy of the artists and Koplin Del Rio Gallery. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

On the right side of the tableau, an astronaut, in the form of the Aztec goddess Coatlicue, gives a Neil Armstrong salute to a flag that is suspended by an iron chain that rises up from the surface of the moon like some kind of magic trick. Though it mimics the structure of the U.S. flag, its stripes are comprised of the diamond patterns that appear on the backs of rattlesnakes, and the stars are transistors. This is a melding of Aztec and high-tech, since the Aztecs are closely associated with rattlesnakes, for historic as well as religious/iconographic reasons.

The Aztecs were initially a lowly, newly-arrived tribe in the Valley of Mexico. Assigned to undesirable snake-infested lands by the Culhua, they persevered and consumed the snakes. After founding Tenochtitlán (the site of present-day Mexico City) in the 1300s, the Aztecs became ferocious colonizers, but they over-expanded their empire, which left them vulnerable to the Tlaxcalan-Spanish coalition that conquered them in 1521.

Coatlicue is a life/death figure as well as an earth goddess, and she is also a monster of sorts. The original statue, now in the Anthropology Museum in Mexico City, slightly over eight feet tall. The de la Torre brothers have reduced her to human scale. Otherwise, she wouldn’t have been able to fit into the spaceship!

Coatlicue wears a necklace fashioned out of human hearts and hands, which terminates in a skull. Her skirt is made out of braided rattlesnakes. The standard interpretation is that Coatlicue gave birth to Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec patron god, at the very moment that she was decapitated (on the basis of an erroneous assumption) by her children, the 400 stars and the moon. For a discussion of interpretations of this complex statue, see my forthcoming article “The Mysteries of the Aztec Goddess Coatlicue” (The New Journal of the Philosophical Research Society). The latter were annihilated and dispersed into space by the righteous anger of Huitzilopochtli, her vengeful newborn child. So the de la Torre brothers’ Coatlicue-cosmonaut, who is now outfitted with a space helmet like Jesús Malverde, is essentially colonizing the body of her defeated, matricidal daughter.

The large backdrop behind the sculptural tableau shows more of the surface of the moon. It is largely barren, though industrious Mexican colonizers have successfully introduced hardy saguaro cacti into this harsh environment. Additionally, the small hills are made of corn chips, and intrepid vendors operate a taco stand beside each one. “That is how our re-colonization begins,” explains Einar.

In the distance, on the far left, we can see the blue earth, which is consumed by flames due to global warming (see the first installation shot of this work).

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Colonial Atmosphere” (detail of Coatlicue/Astronaut from the rear), 2002, mixed media, courtesy of the artists and Kopin Del Rio Gallery. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

A rear view shows the backside of Coatlicue’s two-sided “face.” Rather than a conventional, frontal-oriented face, her face is actually made out of two serpents in profile, which are striking at one another. Consequently, what appears to be her “face” looks the same, whether viewed from the front or the back. The serpents represent the blood flowing from her torso after her decapitation. Mary Miller and Karl Taube call it “a face of living blood.” It is a face of blood. Consequently, Coatlicue doesn’t actually have a head, in the normal sense of the word. Instead, the symbolic image of squirting blood (the two snakes in profile) merely resembles a face, whether it is seen from the front or the rear. One might wonder why she needs a space helmet on the front side, but not on the backside.

Coatlicue wears a large, plate glass-enclosed backpack. The chief article inside of it is a giant human heart made out of red glass, as if she breathes blood rather than oxygen. As we have seen, her apparent head is in fact a manifestation of blood that is spurting like a fountain. Blood, of course, is a vehicle for oxygenating human tissue, but it’s hard to get enough of it when your head has been hacked off.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Colonial Atmosphere” (detail of exterior of lunar module), 2002, mixed media, courtesy of the artists and Kopin Del Rio Gallery. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The exterior of the lunar module is largely covered with tin foil and silver leaf, which stand for the ceramic tiles that cover the ship. They serve to shield the interior from view, unless one looks closely through the gaps or the rear entrance.

In the above illustration, a wood frame encloses objects that, in a church, would be prized relics or offerings. But here, upon close inspection, they are merely crumpled beer cans. Refuse — in the hands of the de la Torre brothers — appears to be both precious and sacred.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Colonial Atmosphere” (detail of interior of lunar module with the Christ child on a stuffed rocking horse), 2002, mixed media, courtesy of the artists and Kopin Del Rio Gallery. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Peering into the interior, one is astonished to see that the spacecraft is operated by the Christ child. He rides (reverse bareback) on a crudely stuffed rocking horse. (I almost expected to see a bumper sticker that reads “Jesus is my co-pilot.”) This horse, which has a bloody mouth, is meant to connect Christ with the Apocalypse. Einar gave me this explanation:

Jesus is riding it to colonize a new world. The Olmec head as a capsule is a throwback to the initial cultures that dominated the region, way before the Maya or Aztecs. And the juxtaposition with the holy child is the futurism that mestizaje implies.

This “second coming” of the light-skinned Christ is collapsed onto the myth of Quetzalcoatl, and his promised “return” in Mesoamerican lore.

The brothers did not have a specific form of the Christ Child in mind, but I like to think of him as the Santo Niño de Atocha (see my Glasstire article Esquivel 2), because that holy child is a pilgrim who wears a conch shell as an emblem of pilgrimage. The child in Colonial Atmosphere instead has a string of mussel shells.

This Jesús-stronaut’s position immediately suggested to me the fraudulent, but highly influential theories that were cynically advanced by the Swiss hotel manager Erich von Däniken. In his best-selling work of pseudo-archaeology, Chariots of the Gods? (first published in English in 1971), von Däniken claimed that the sarcophagus lid from the tomb of Pakal (who ruled the Maya site of Palenque from 615-683) depicted an ancient astronaut from outer space who redirected the course of human history.

For an illustration of a rubbing of the relief on Pakal’s lid (and a short refutation of von Däniken’s theories), see Stephen M. Epstein, “Scholars Will Call It Nonsense” Expedition Magazine 29:#2 (1987).

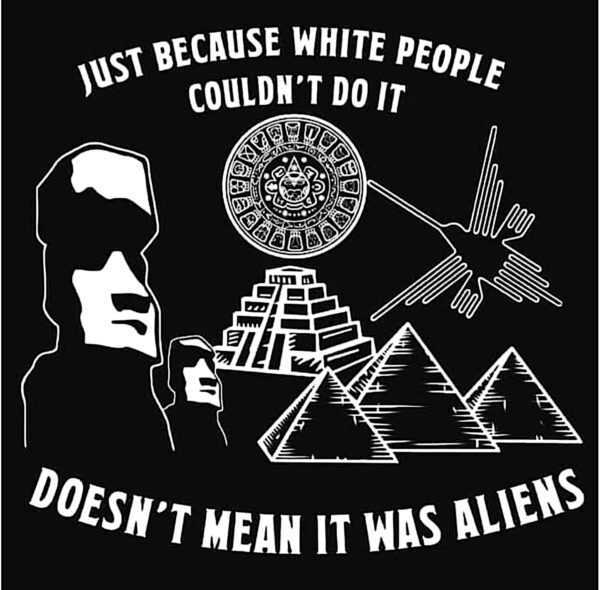

One mark of von Däniken’s influence is the fact that the History Channel (maybe it should be called the anti-History Channel) is rife with “documentaries” about ancient aliens who constructed non-European monuments. They play into racist tropes that presume that people of color could not have built these ancient wonders without assistance from a superior, foreign intelligence.

“Just Because White People Couldn’t Do It Doesn’t Mean It Was Aliens,” meme available as sticker, t-shirt, etc.

The meme “Just Because White People Couldn’t Do It Doesn’t Mean It Was Aliens,” refutes this kind of racist assumption.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Colonial Atmosphere” (detail of exterior of lunar module with modified relief of King Pakal), 2002, mixed media, courtesy of the artists and Kopin Del Rio Gallery. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

To help the viewer connect the posture of the Christ child to the relief on Pakal’s sarcophagus lid, the de la Torre brothers have included two images of Pakal in cast polyester resin on the exterior of the spacecraft (one on either side of the crushed beer cans).

Implicitly, then, Pakal is a revered ancestor-astronaut figure, a pioneer of space travel whose image adorns either side of the space capsule’s entrance. Thus he is an indigenous space traveler rather than an “alien” one.

In a cartouche above Pakal, one can see three figures of Christ with his crown of thorns, the first of which is framed by his cross. They are utilized as decorative arrangements.

The de la Torre brothers’ utilization of Mesoamerican monuments as agents of extraterrestrial colonization reminds me of what Enrique Chagoya, in his own artistic practice, refers to as Reverse Anthropology. I describe it as a strategy that “upends the normative colonizer-to-colonized relationship” (see my Glasstire article, “Enrique Chagoya’s Superheroes and Super Villains,” Aug. 19, 2019). Chagoya also cannibalizes and/or appropriates Western images, and he often reverses conventional significations to create temporal, geographic, and cultural mashups. Einar, in the context of an exhibition in Portugal, noted: “We’re retro-colonizing Europe with our work” (DTBC).

The de la Torre brothers have situated major Mesoamerican monuments on the moon. They mashed them up with space-age technology. Moreover, the Christ child is, in this context, a somewhat alien blonde astronaut, one who serves explicitly as an ironic — and very unexpected riposte — to von Däniken’s theories. This god-pilot is not a god from another galaxy, but rather the god of the Catholic colonizers of the planet earth.

While von Däniken would have us believe that aliens from outer space are responsible for monuments built by non-European peoples (as well as an upgrade to human DNA), the de la Torre brothers endow specific Mesoamerican monuments with space agency. The Christ child is pressed into service as the ghost in their machine, the god-child spaceship pilot, who is a successor to Pakal, the mighty Mayan from Palenque.

In Colonial Atmosphere, the earth has been rendered uninhabitable by over-development: it has an excessively colonized atmosphere. The moon, by contrast, is almost altogether lacking in actual atmosphere. The paucity of natural resources (beginning with air and water) makes it a difficult place to colonize. Only the hardiest flora (cacti) and colonizers (Mexicans) can survive. Jamex provides another angle on the title Colonial Atmosphere: “It sounds like they’re trying to sell you a hotel in Mexico or something, with a very ‘colonial atmosphere’” (DTBC).

Colonial Atmosphere is not part of the traveling Collidoscope exhibition, but it is featured in the exhibition De la Torre Brothers: Post-Columbian Futurism (March 18 – Aug. 20) at the Institute of Contemporary Art, San Diego.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Ruleta Azteca,” 2004, blown glass and resin, courtesy of Eleana and David Del Rio. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The Aztec Stone of the Sun (also known as the Aztec Calendar, though it is not technically a calendar) is as much a part of Mexican identity as the national flag. The de la Torre brothers grew up with a reproduction of it on a family coffee table in Guadalajara, on which they played with matchbox cars in the 1960s.

They also note that it is on Mexican currency, on the jersey of the Mexican soccer team, and in virtually every Mexican restaurant. See Local Guides Connect for images of the Stone of the Sun and portions of it on Mexican coins.

The de la Torre brothers have made a number of works loosely based on the Stone of the Sun that they refer to as mandalas (an ideal symbol of the universe, often used for meditation).

Ruleta Azteca turns the Stone of the Sun into a lottery wheel. The face in the center of the original Stone of the Sun, which is usually identified as the Aztec sun god Tonatiuh (with a protruding tongue that is actually a sacrificial knife), is here blown up into an enormous stylized metal effigy. This shiny face is in the center of a star, whose points alternately terminate in either a bride and groom couple, or a large image of the original Virgin of Guadalupe (an elaborately costumed Romanesque black Madonna in Extremadura, Spain). The outer ring features prizes, which include matchbook cars, like the ones the brothers played with on their Stone of the Sun coffee table.

Jamex noted that the brothers were included in an exhibition called Ultrabaroque: Aspects of Post-Latin American Art. (This exhibition served as my introduction to their work when I saw it at SF MoMA in 2001.) Jamex says the show demonstrated that Latin American artists inherited baroque qualities from indigenous civilizations as well as Spain, resulting in a double baroque heritage, a legacy he heartily affirms (DBTC).

We see this dual heritage in many works in Collidoscope. A number of objects share the structure of the Aztec Stone of the Sun, yet they brim with colorful ornamentation, like a holy object covered with shiny offerings in a Catholic church. Multiple influences are also evident in works discussed below.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Soy Beaner” (which could translate as “I am a beaner,” or “a beaner of soy”), 2007, video and mixed media, spoken word performance by Paul ThaiMex Phruksukarn, courtesy of the artists and Kopin Del Rio Gallery. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The work that became Soy Beaner was commissioned by the Galería de la Raza in 2007. The brothers scoured stores (including dollar stores) in San Francisco’s historic Mission District to find materials to utilize in the work.

They incorporated objects such as beer bottle clocks with the inscription “Dadweiser” and “Borona” (grain), as well as springy crabs, and African sculptures reproduced in resin.

“Only the transparent pieces are cast by us,” says Einar, “like the Veracruz faces full of soy beans and the ‘pie wedges’ that are directly referencing the Aztec Calendar.” All of the other elements are examples of material culture that were sourced and appropriated from Mission District stores.

Soy Beaner is a work of cultural synthesis. The wallpaper background mixes flying dragons with flying Virgins of Guadalupe. The latter have a fiery exhaust beneath them, as if they were jet-powered.

Aztec day signs and symbols of eras are scrambled with appropriated kitschy clocks. The face of Tonatiuh in the center, is here replaced by an illuminated “border Buddha,” though it retains some of Tonatiuh’s features.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Oxymodern,” 2002, photographed with exhibition curator Selene Preciado, 2022, blown glass and mixed media, gift of Cheech Marin. Photo: courtesy of Selene Preciado.

In the original Stone of the Sun, four cartouches in the center held symbols of the destruction of the four previous ages. See the image in Local Guides Connect that outlines the Ollin glyph in lime green. The four cartouches (as well as the head of Tonatiuh) are contained within the Ollin glyph, which stands for movement, which symbolizes how the fifth (Aztec) age was destined to end (through earthquakes).

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Oxymodern” (detail of center), 2002, blown glass and mixed media, gift of Cheech Marin. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

In Oxymodern, the brothers have substituted four squares that are framed by dominoes. They contain the following: a hand holding a gun, a hand holding a knife, a lower limb with a Nike soccer cleat, and a lower limb with a cowboy boot and spur. The conceit is that these images symbolize the forces that caused the destruction of the four previous eras. These limbs all have rattles, like those worn by indigenous dancers from past eras, as well as contemporary re-enactors.

The outer ring has eight plates, each of which serves up a human heart. Though the plates are modern, the meal is “traditional.” This melding of old and new reflects the title, which is an amalgamation of oxymoron and modern.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Eastern Medicine” (detail of center), 2002, blown glass and mixed media, gift of Cheech Marin. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Eastern Medicine (2008) is another notable mash-up of the Stone of the Sun. It alludes to Eastern medicine and ways of healing, which include herbs and food remedies, as did the healing arts in the Americas. Ears of corn are in the four cartouches, and tomatoes take the place of the clawed hands on either side of the face within the Ollin glyph. Eight images of the top half of the Virgin of Guadalupe extend from the work’s outer ring.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Eastern Medicine” (detail of Kabuki-style Virgin of Guadalupe), 2002, blown glass and mixed media, gift of Cheech Marin. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

These eight Virgins of Guadalupe have brightly colored costumes and extremely pale faces. The latter are obviously the product of face powder. This artificially lightened skin is a significant anomaly, since the dark skin color of the original Guadalupe painting attracted indigenous and mestizo devotees. It is a characteristic that is still valued by many contemporary Mexicans and Chicanos, whether they are devout Catholics, or people who relate to the dark-skinned figure on a cultural level.

How did this dark-skinned image originate? Jeanette Favros Peterson considers the possibility that, as others have proposed, a painting of a “racially corrected” (i.e. dark) virgin was commissioned by Archbishop Alonso de Montúfar around 1555 in order to “lure the indigenous constituency.” She thinks it is just as likely that Marcos, the indigenous painter, “reformulated the new Christian deity for reasons of self-identification. The native artist co-opted the European Madonna image by converting other into self” (“Creating the Virgin of Guadalupe: The Cloth, the Artist, and Sources in Sixteenth-Century New Spain,” The Americas, 61# 4, 2005, pp. 609–610, JSTOR.)

Over a base of stark white powder, the eight virgins in Eastern Medicine have boldly rouged cheeks, tiny red lips that are tightly pursed, varying degrees of eye shadow, and emphatic short, black eyebrows. These virgins are rendered Kabuki-style, in terms that are meant to be sexually alluring to a traditional Japanese audience.

Kabuki Theater banned women in 1629 to prevent the practice of prostitution. Patrons, nonetheless, were still attracted to the elaborately made-up male actors, and some male actors engaged in prostitution with theater clients. Consequently, these eight de la Torre “virgins” could be cross-dressing impersonators of the Virgin of Guadalupe, as well as male prostitutes.

Eastern Medicine was made after the brothers had done a teaching stint in Japan. They note that Kabuki actors are now mixed gender. Einar also points out that the photographs of food (now faded) are from an udon restaurant, connoting “Eastern medicine through good nourishment.”

Einar recalls that a painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe from the late 1800s hung above the Stone of the Sun coffee table in the family’s home in Guadalajara. Einer refers to these two images as “the two most overused symbols in the Mexican lexicon.” After the brothers had done their own share of overusing these two symbols over a period of years, they remembered how prominently they had been juxtaposed within their childhood home. They also sought to redeploy these images in unconventional, critical terms.

Mythic figures tend to have extraordinary births. See Otto Rank’s The Myth of the Birth Of The Hero: A Psychological Interpretation of Mythology, originally published in 1909. According to the faithful, Jesus was conceived without sex. So, too, was Huitzilopochtli. But Christianity’s anti-sexual basis set it apart from other religions. It developed the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception to maintain that Mary, mother of Jesus, also was born without sex.

Peterson notes the dilemma posed by Mary’s dual nature, which resulted in

… the need to reconcile her humanity, and thus her subjugation to original sin, with the idea that she had been conceived free from concupiscence and was therefore unsullied or “spotless” in nature (in Latin, non-maculata or immaculate). Of all women, Mary was singled out to embody the unique combination of divinity and personhood, a dual nature that expressed itself simultaneously as pure virgin and fecund mother” (“Creating the Virgin of Guadalupe,” The Americas, pp. 590-91).

In Catholicism, the Virgin Mary is held up as a supreme exemplar, though she is quite impossible to imitate. When the de la Torre brothers rework the Virgin of Guadalupe, they address some of the contradictions inherent in the Catholic conception of this mother of god.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “La Belle Epoch” (the beautiful age), 2002, kinetic mixed-media, blown-glass installation, 120 x 144 x 36 inches, courtesy of Einar and Jamex de la Torre and Koplin Del Rio Gallery. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Originally made for Grand Arts in Kansas City, Belle Epoch is intended as a kind of Aztec sun stone for that civilization’s “beautiful period.” It looks like a big Ferris Wheel, but it has two interlocking wheels that rotate at different speeds. For some footage of the wheels in motion, see the video De La Torre Brothers Interview | Cheech Marin’s Chicano Art Tour, 2022.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “La Belle Epoch” (the beautiful age; detail of lower center area), 2002. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The central figure holds a knife in his left hand and beer in his right hand. He is presumably an updated Aztec.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “La Belle Epoch” (the beautiful age; oblique view), 2002. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The outer wheel features human hearts around the perimeter. These hearts drip blood into the canoe beneath the wheel. Each individual heart, in turn, has an individual inscription that explains how the person it came from died. These inscriptions were inspired by products sold by vendors in Guanajuato, Mexico, at a site that displays mummified human remains. These vendors sell little candy mummies that are inscribed with the purported reason for their demise. Einar says the “Mexican dark humor” of the candy mummies appealed to the brothers so much that they were inspired to make their own variation of them.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “La Belle Epoch” (the beautiful age; rear view), 2002. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Einar characterized the sculpture as “a well oiled timepiece with objects that represent the culture.” The Mexican national emblem, the eagle with a snake in its beak perched on a cactus, is situated in the center of the rear side of the installation.

Other elements include four bicycle tires, two of which have a trio of multi-colored Virgins of Guadalupe inside of them. One has an empty aureole, and the other has a skull topped by a cross.

There are also several skull-headed mannequins (either transparent or white) that have hollowed-out chest cavities. Crosses bearing a sculptural image of Christ’s head have been inserted into them. One can interpret these figures as symbols of the forcible insertion (and subsequent internalization) of Christianity into indigenous bodies.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Tula Frontera Norte” (Tula, northern frontier; pair of atlantid figures), sheet-glass construction with video, 9 feet tall, courtesy of the artists and Koplin Del Rio Gallery; and “Critical Mass,” 2002, blown-glass, mixed-media wall installation, 84 x 192 x 10 inches, courtesy of the Cheech Marin Collection and Riverside Art Museum. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

This pair of glass constructions emulates the giant Atlantid warrior figures found at the Toltec site of Tula (900-1200 AD), though they are much shorter than the imposing 6.1 meters of the original sculptures. Einar says they are like aquariums, filled with multi-media elements, as well as glass and appropriated objects. Made at the turn of the millennium, they were outfitted with VCR players, which had to be transferred to digital before they could be viewed at The Cheech.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Critical Mass,” 2002, blown-glass, mixed-media wall installation, 84 x 192 x 10 inches, courtesy of the Cheech Marin Collection and Riverside Art Museum. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

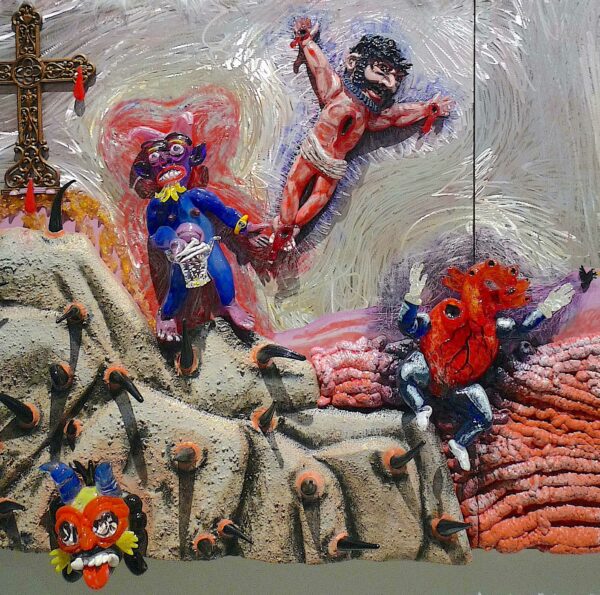

The title Critical Mass refers to the scientific term for the amount of fissionable material necessary to sustain a chain reaction, and also to criticism of the Catholic mass. The four supporting panels are made out of aluminum. A grinder was applied to the panels to provide depth and painterly effects.

There is a whole lot going on in Critical Mass. At the top, the sun itself has been colonized by the Spanish. Like the Stone of the Sun, it has an Aztec face with a protruding tongue (which, in the original, is a sacrificial knife) in the center. Seven of the eight rays terminate in ears of corn; the eighth terminates in the head of a Spaniard.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Critical Mass” (detail of left side), 2002, blown-glass, mixed-media wall installation, 84 x 192 x 10 inches, courtesy of the Cheech Marin Collection and Riverside Art Museum. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

On the far left, the devil, who witnessed Christ’s suffering on the cross, released him by excising his heart and removing the three nails, which he holds with his right hand. This liberation from the cross was “much to Christ’s chagrin,” says Einar. Christ floats in the sky without purpose, still locked in his cruciform pose, as he impotently surveys the mayhem that takes place in the center of the piece.

The devil’s actions serve as a reversal of the religious colonization enacted by the Spanish. In Catholicism, the Eucharist — the consumption of Christ’s transubstantiated sacrifice of flesh and blood — provided a ritual that was forcibly substituted for the practice of literal heart sacrifice on the part of people the Spanish regarded as superstitious pagans. In Critical Mass, a literal reenactment of Aztec heart sacrifice liberates Christ — evidently quite against his will — from the central act of Christian sacrifice.

A big loser in this reverse colonization is the anthropomorphized Sacred Heart, who, now that he is deprived of his important role in Catholicism, raises his pale white hands in dismay. Christ’s colonizing heart has been appropriated by the devil, who behaves like an Aztec priest re-enactor.

The hill of Golgotha (by tradition the site of Christ’s crucifixion outside of Jerusalem) is barren, even though an image of Tlaloc, the goggle-eyed Aztec rain and fertility god, is at the bottom of the hill. Only aggressive-looking spikes or talons seem to grow on Golgotha.

The ground between Golgotha and the Basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico City is pink and thickly textured. Aztec priests, who actively practice heart sacrifice, brandish a human heart in each hand. Birds gather above them to feed on human carrion. Fashioned out of foam expanding insulation, this pink ground, according to Einar, is meant to evoke “bloody guts.” He adds that the Aztec sacrifices make the fields fertile, because sacrifice and fertility go hand-in-hand.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Critical Mass” (detail of upper center), 2002. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Near the center of Critical Mass, an enthroned, suit-wearing figure is perched amidst the fake-fur clouds. He is San Simón (also known as Maximón), an avaricious, womanizing trickster figure that is regarded as a saint (akin to a minor deity) in folk religion, especially among the Maya in Guatemala and Mexico. San Simón prefers offerings of alcohol, cigarettes, and money. He is depicted with moneybags because he brings prosperity, as well as success in love.

San Simón usurps the place held by God the Father in conventional Catholic images. Moreover, he actively attacks the Basilica of Guadalupe because the money bags he possesses are not sufficient for his greed. No less than six silver-surfaced images of the Virgin of Guadalupe are fired by San Simón at the basilica. These silver bullets from heaven fly and turn like precision guided missiles. Unlike Guadalupe, who has flames at her two sides, these guided Guadalupes emit a flaming exhaust from their bases. The first of them has already struck a tower, causing it to collapse. As Einar informed me, “the ‘beatas’ are fired to bring down the twin towers of the church,” which will enable San Simón “to take church money.”

Above the basilica on the right, one can see the hill of Tepeyac, where the convert Juan Diego kneels, with his tilma full of roses. This is part of the origin myth of the purportedly miraculously-created image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, which involves roses. I discuss this connection in my Glasstire article José Esquivel 2. (The rose becomes an enduring symbol in Esquivel’s art.) Jeanette Favros Peterson rebuts the pious account of the image’s creation in the 2005 article in The Americas that is cited above.

The hill of Tepayec is fashioned out of a multitude of heads. Many of them belong to pre-Columbian “smiling figures” from the Gulf Coast (which were mortuary statues buried with human remains), though some have European features. According to Einar, they represent “the ruins of cultures, past and present.”

Juan Diego should be looking at the Virgin of Guadalupe, since this figure is enclosed within a mandorla with fiery rays, but the virgin’s human form has been vacated. All that remains within the Virgin of Guadalupe’s mandorla (an almond-shaped full-body aureole) is a vaginal form that is anthropomorphized with human limbs, like the Sacred Heart on the other side of Critical Mass. In a parallel that goes back many centuries, some medieval pilgrim’s badges featured ambulant, anthropomorphized human genitals. (See Ann Marie Rasmussen, “Wandering Genitalia: Sexuality & the Body in German Culture between the Late Middle Ages & Early Modernity,” King’s College London, Centre for Late Antiquity & Medieval Studies, Occasional Publications, 2, 2009.)

Mandorla is an Italian word that means “almond.” The de la Torre brothers frequently deploy an image of the labia majora as a kind of mandorla (an almond-shaped glory). Thus they subversively substitute an image of female genitalia for the sacred Catholic image. They refer to their image as “the portal of life.”

Since the Virgin of Guadalupe is a longstanding tool for religious and political colonization, her elimination can be viewed as a decolonizing action. I asked Einar whether the gesture of eliminating Gaudalupe from her mandorla was explicitly intended as an act of decolonization.

He replied:

Our intent originally was not so much to deconstruct the Virgen de Guadalupe, but of course this has been part of everything we do in terms of using the over-wrought cultural symbols. We noticed early on that — just as the image of Jesus on a cross is very masculine and rigid — the virgin looks like a vulva (portal of life) and we have [made] many installation using these symbols to talk about identity and gender.

I inquired when the “portal of life” was first deployed in their art, whether their conception of it had changed over time, and if it is the motif they have utilized the most. It turns out that the brothers first used it as part of a wall installation in the Ultrabaroque exhibition, which premiered at the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego in 2000.

Einar adds:

Inevitably such potent symbols change in our contextualization over the years. Back then, gender issues where [a] fairly simple binary. It is one of our motifs that has endured, for sure. Perhaps the most, but we do not keep count, LOL.

The earliest installations that featured the “portal of life” utilized numerous examples interspersed with various forms of crosses and crucifixes, all of which were made of blown glass. Hence they were binary, gendered signs displayed as part of a field with considerable individual variation. In tableaus like Critical Mass and Exporting Democracy (discussed below), a single “portal of life” has a critical position, though, in both cases, it still functions in conjunction with one or more crosses.

In addition to doing away with the figure of the Virgin of Guadalupe in Critical Mass, the brothers have also eliminated her traditional colors, which are green and rose pink. Instead, they have dressed the vulva figure in the uniform of the Chivas, one of the preeminent Mexican soccer teams, which is based in Guadalajara. For many Mexican soccer fans, their devotion to the sport is almost like a religion. Incidentally, an uncle of the de la Torre brothers served as the coach of the Chivas in the 1960s, during which time he won six championships, so they are well acquainted with futból-mania and idolatry.

The right side of Critical Mass is dominated by a “cheeky monkey,” who serves as the narrator of this story. Uniquely, the area around the monkey is bursting with flowers and vegetation, including roses, which, as noted above, are associated with Guadalupe. It is the only area of the work that is fertile.

I inquired whether the monkey’s randy sexuality and the concomitant absence of religion were the factors that enabled fertility. Einar replied that perhaps the sacrifices brought more pain than fertility, whereas the monkey comes from the fertile jungle. Einar also specified that the narrator was a gay monkey.

I inquired whether the monkey’s sexual identity had particular significance in Critical Mass. Was his story, for instance, a way of countering (or imagining an end to) the homophobic policies of the Catholic Church and the Mexican nation? Is his sexual identity an avenue for deconstructing repressive gender roles? Is a gay narrator expected to be more informed and more concerned with these roles than a straight narrator?

Einar gave this explanation:

The gay monkey was a nod to a very dear curator/friend, as we imagined him telling the story of this allegory. The monkey is an outsider, so yes, he has a different viewpoint, and perhaps a better social commentary.

On the issue of their religious upbringing, Jamex noted in a filmed talk on the Collidoscope exhibition:

We obviously grew up Catholic…. We are not religious at all anymore. But the artistic tradition of the Catholics is tremendous. So for us to draw from it is absolutely a natural. We spent so many hours completely bored in churches as kids. But all that richness — you can see the effect that it had on us (DTBC).

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Pecking Order,” 2002, blown glass and mixed media, courtesy of the artists and Koplin Del Rio Gallery. Photo: Phillip Rittermann.

The central figure in Pecking Order is an amalgamation of a literal-looking Corn Deity and the artists’ characteristic “portal of life” (the mandorla of the Virgin of Guadalupe after she has been evacuated from it). A reminiscence of Guadalupe’s green mantle seems to collapse seamlessly onto the outer husk of the corn.

Einar refers to this figure as “a corny vagina.” The circular form at the top, which bears a blue cross that is fashioned from glass and rhinestones, is suggestive of a clitoris.

Four roosters — one might term them symbolic “cocks” — stand in red areoles in the four corners of the piece. They are positioned where subsidiary holy figures would be situated in a traditional religious painting from the colonial era. These metal-stamped roosters have an aggressive mien, which is amplified by the oversized eyes that are superimposed on them, all but obscuring their heads. They are eager to have their turn with the Corn Deity.

Beneath the ear of corn, a Gachupín looks out with disapproval. (Gachupínes were Spaniards born in Spain, a class of people who had the highest status in colonial Mexico. They were also mocked with glee.) This Gachupín figure is a resin cast (filled with actual kernels of corn) taken from a folk mask from Michoacán. His green eyes match the colors of the husks.

Like Critical Mass, Pecking Order is mounted on aluminum, and coloristic effects have been achieved by grinding and the addition of glitter. The jewel-like reds were created with translucent red paint applied directly to the aluminum. The brothers utilized bright colors to achieve an effect like “a Mother’s Day card.”

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Exporting Democracy” (main panel), 2006, blown glass and mixed media, courtesy of the artists and Koplin Del Rio Gallery. Photo: Phillip Rittermann.

In one of the de la Torre brothers’ most contentious political works, a virtual spider’s web (in high relief) covers the map of the United States. This web is made of tripe, which, in the U.S., connotes something that is absurd, untrue, and/or worthless. A gaping mouth is situated at the end of each strand of tripe. These aggressive mouths are directed outward. According to Einar, they express a wish “to consume all.”

A kaleidoscope of Monarch butterflies emerges from the “virgin portal” in the center. They are “birthed” from it. These butterflies have crucifixes instead of bodies. Alarmingly, as in a horror film, when they fly far enough away from their source, they metamorphose into silver-colored “Jesus Christ jet fighters,” which sport crucifixions on their bellies.

Exporting Democracy was made for the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego during Bush II’s Iraq War. “Exporting Democracy” had become the imperial catch phrase of the moment, a pretext for conquest and domination, much like religion had been in earlier ages.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Exporting Democracy” (image on the right, with crucifix butterflies suspended from the ceiling), 2006, blown glass and mixed media, courtesy of the artists and Koplin Del Rio Gallery. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

For the installation at the Cheech, the de la Torre brothers added images of retablos (ex voto paintings made in thanks for an intercession) from the Parish of the Immaculate Conception, a pilgrimage church in Real del Catorce in the state of San Luis Potosi.

Mischievously, within the paintings they appropriated, the brothers sometimes substituted Uncle Sam “as a replacement deity” for Christ, the Virgin Many, or some miscellaneous saint. Einar notes that while the U.S. wanted to impose “American-style democracy,” any authentic democracy “has to develop as part of the culture,” from internal forces and institutions, or it will not work. He adds that the U.S. is currently “having an existential crisis with its [own] democracy now.” So it is hardly an exemplary model to export to the rest of the world, especially to countries the U.S. invades, purportedly for the sake of democracy.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Exporting Democracy” (detail of Jesus Christ fighter jet, from installation at the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego), 2006, blown glass and mixed media, courtesy of the artists and Koplin Del Rio Gallery. Photo: courtesy of the de la Torre brothers.

While Monarch butterflies are often utilized as symbols of immigration, in this work they become a component in the forcible imposition of one belief system onto another one. The de la Torre brothers understand that a political/religious system cannot be readily imposed on another country. The butterfly crucifixes and the Jesus fighter jets symbolize the true nature of the U.S.’s intended “conversion.”

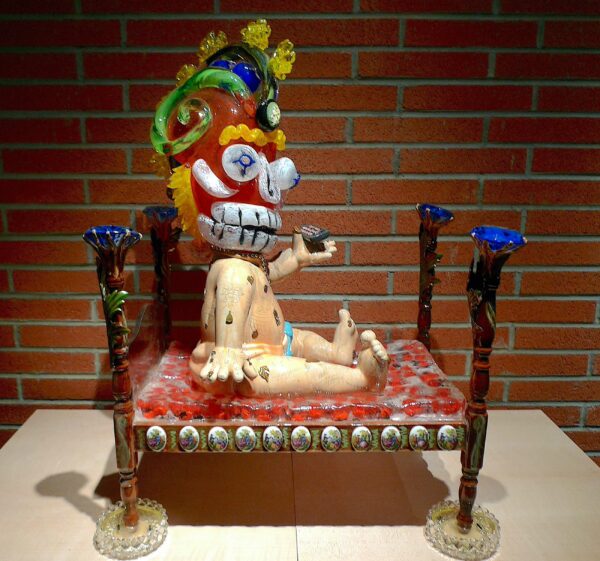

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “¡2020!,” 2020, mixed-media, blown-glass sculpture with resin casting, 33 x 22 x 14 inches, courtesy of Koplin Del Rio Gallery. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The de la Torre brothers discuss ¡2020!:

It used to be that when a year starts, you had a new year represented as a new baby and the old year walking out as an old man. So 2020 to us was ominous because of the pandemic and Trump’s shenanigans. So we decided that it had to be a very nasty-looking baby. So, to talk about material culture, that baby is a display at a pharmacy, probably. We found it, we spotted it at a flea market, or something. We sawed its head off — not in a grisly manner. And then we replaced it with a blown glass piece, which is, of course, of our own manufacture. The bed is a bed of roses. That’s cast resin. … And, again, it’s 2020: this year that will end up in infamy (DBTC).

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “¡2020!” (detail), 2020, mixed-media, blown-glass sculpture with resin casting, 33 x 22 x 14 inches, courtesy of Koplin Del Rio Gallery. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

This ugly baby has a skull head (note the nose cavity and the protruding teeth), green snakes instead of ears, and yellow COVID-19 viruses on the rim of its headpiece.

As the newborn rests on its bed of roses, it holds a remote control in its left hand. It already boasts tattoos, and metal votive offerings attached to its flesh. Nonetheless, like other babies, it wears a diaper, which is attached by a large blue safety pin.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, Pancho/Roomba installation, 2017, Glasmuseet, Ebeltoft, Denmark. Photo: screen grab (DTBC).

In their filmed talk on the Collidoscope exhibition, the de la Torre brothers discuss a work they made in Denmark. They placed a stereotypic image of a sleeping Mexican with a big hat (which they refer to as a “Pancho”) atop a Roomba.

In connection with this work, Jamex noted that while Mexican workers have “the longest hours in the world,” Danes are in the process of whittling their working week down to four days. Nonetheless, the stereotype of the “lazy Mexican” persists.

Einar offers this succinct commentary: “He’s lazy and he’s sleeping, but he’s still sweeping” (DTBC).

The brothers should definitely make a limited edition of this work, perhaps casting the “Pancho” figure in impact-resistant resin!

Gaiatlicue: A Permanent Installation at The Cheech

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Gaiatlicue,” large-scale lenticular print installation, 26 x 13 feet, permanent installation at The Cheech, Riverside Art Museum. Photo: Genevieve Cordova from the second floor balcony.

I end this review with a work that is technically not in the Collidoscope exhibition, which was on the second-floor galleries devoted to temporary exhibitions. This enormous lenticular work is called Gaiatlicue. It was commissioned for The Cheech in 2022, and it greets visitors as they enter the lobby on the ground floor.

The name Gaiatlicue is a combination of Gaia (the Greek primordial goddess that personified the earth) and the Aztec goddess Coatlicue. While the latter, as noted above, was a complex life/death goddess, she, in combination Gaia, is here presented as what Einar calls “a defender of the earth — ‘mother earth.’”

Coatlicue (with Ruben C. Cordova), Aztec, c. 1487-1520, from Tenochtitlán, stone, 8 feet, 3 inches high, National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City.

The large Coatlicue in the Anthropology Museum is a useful reference point. Two contrasting versions of it were made by the de la Torre brothers, which they combined to make their lenticular print. Though this Aztec Coatlicue is large, the de la Torre brothers’ version is much larger.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, two digital images that are combined to make “Gaiatlicue.” Photo: Einar and Jamex de la Torre.

A lenticular print (there are several in the Collidoscope exhibition) combines two images. They are cut into thin strips, and alternating strips from the two images are laid side-by-side and combined into a single image. The two images reproduced above were merged to become Gaiatlicue.

The finished, composite image appears to change when it is viewed from even slightly different angles. For the de la Torre brothers’ explanation of how a lenticular print is made, the meaning of this work, and views from different angles, see the video Cheech Marin reveals the first art going into The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art Art & Culture, 2022.

The image on the left, associated with Gaia, has the structure of the Aztec Coatlicue statue, though her arms are akimbo, like Wonder Woman. She is made out of flora and fauna, including moths’ wings, coral snakes, and flowers for a head. A balduchin with angels is positioned above her head.

Large frogs sit on her shoulders besides goldfish (they are well camouflaged). Tortoise shells are substituted for the first set of human hearts. Her braided snake skirt is fashioned out of braided vegetation. The skull resembles a de la Torre glass sculpture, so it is more comic than grisly. This woman has toucan beaks that form the claws on her feet. The macabre monster eyes-on-the-feet have been prettified. A pair of lovebirds are perched on the claws of each foot, an indication that this Gaia-inspired figure is not as fearsome as the Aztec original.

This woman stands on the earth. The United States and Mexico are positioned in the center (a red linear map of the hemisphere is superimposed over it). On the edges of the earth, one can make out the outer band of the Aztec Stone of the Sun, in a fashion similar to what appears on Mexican coins, as noted above. Purple pre-Columbian figures stand on the rim of the earth.

As Gaia, this figure represents nature, though some schematic architectural elements appear in the background, and, at the very top, one can see a church-like dome, with figures in niches. Nature does not stand apart from humanity.

As Einar notes: “She is defending nature and perhaps angry at our horrible ‘husbandry’ of nature and the resources as just ‘expendables.’”

The image on the right is a Coatlicue fashioned out of low rider automobile parts. The parts are sourced from photographs the brothers took at Chicano Park in San Diego.

A collage of blue car parts and an elaborate grill make up the face of this retro-industrial Coatlicue. The front end of a Chevrolet forms her torso, and her necklace is made out of wire hubcaps, four of which are fashioned into hands.

Multiple hummingbirds hover on the (proper) left side of the mechanical Coatlicue. They are a reference to Huitzilopochtli, Coatlicue’s vengeful son, whose name means “Hummingbird on the Left.” The front and rear ends of cars comprise her braided skirt. Cleverly, the talons on the mechanical Coatlicue’s feet are made of vintage taillights.

In the background, we can make out many solar panels, as well as a pair of trains. The highways are bedecked with garlands of flowers that are native to California. Mass transit and solar energy are thus envisioned as solutions to the problems caused by the auto-industrial age.

As in Colonial Atmosphere, this industrial Coatlicue stands on the moon. In this instance, it features a map of East Los Angeles. The dome at the top is like the dome of heaven, glimpsed through clouds, like an illusionistically painted Baroque church. It features a map of Riverside. The highways in the background traverse these two centers of Chicano culture.

Einar provides this analysis of the Lowrider Coatlicue:

it is in a ‘Transformer movie’ stance, and meant to signify that while the Industrial Revolution has us in a global warming nightmare, it will take science and technology (perhaps ironically) to get us out of it.

Gaiatlicue is consequently a synthesis of nature and technology (both rendered in the form of Coatlicue), whose dual needs must be reconciled in order to continue to provide a fit habitation for the human species.

Einar and Jamex de la Torre, “Gaiatlicue” (detail from right side of second floor balcony), large-scale lenticular print

In the above detail of Gaiatlicue, one can see that (from the angle I photographed it) the head and torso are primarily automotive, but the skull resembles the glass-like skull in the Gaia version. The figure’s left arm is made of flora and fauna (including the frog and goldfish at the shoulder). One can see traces of both arms on the other side of the figure. In the lower body, the skirt is automotive on one side, and made of flora on the other. At the bottom, one foot has toucan beak claws, and the other has headlight claws. One only needs to move a fraction of an inch to change what one sees.

Lenticular works are made for human eyes, which have stereovision. Unfortunately, the camera monovision fails to capture the sense of depth human eyes perceive when viewing lenticular prints, and it also fails in capturing a well-focused image. So there is no good approximation for seeing something like Gaiatlicue in person.

Conclusion

In this review, I have concentrated on a limited group of works and subjects. The de la Torre brothers have utilized some of the most famous Mexican cultural icons (the Olmec head, Coatlicue, the Stone of the Sun, the Sacrificial/Sacred Heart, the Virgin of Guadalupe) in a critical, subversive, and de-colonizing frame of mind (often with a heady dose of dark humor). Their work operates on multiple levels, and their commentary is more serious than it often appears to be on the surface. For this reason, I think more explanatory texts within the show would be highly desirable, because, in many cases, even very well -informed visitors would have a hard time understanding many points that the artists are making, or the crucial stimulus that inspired them to create a particular work. Additionally, as in the case of ¡2020!, for instance, visitors to the exhibition miss out on the hilarious commentary the artists have made elsewhere.

Einar made a very insightful comment on universality and individual vision. He cautions against seeking excess universality:

The problem with trying to be universal is that you lose identity. If you try to be like everybody, you actually forget who you are. Because everybody’s gonna like it, that’s just an aesthetic decision of making something pretty. You still need to retain the fact that you came from somewhere and your work has that information of you and where you came from in some way (DTBC).

He also warns that work can become too hermetic, such that it “can be so personal that it’s only self-referential and maybe not interesting to other people, and so there is always a balance” (DTBC).

Collidoscope is an extraordinary exhibition, one that draws from deep experiences (both aesthetic and social) within Mexican culture. In their work, the de la Torre brothers interrogate these experiences; they invest them with satire, with a concern for social justice, and with hope for the continued survival of the human race.

***

The Collidoscope exhibition is the product of a collaboration between The Cheech Marin Center of Chicano Art & Culture of the Riverside Art Museum (“The Cheech”) and the National Museum of the American Latino (NMAL), which was formally created by Congress in 2020. The project began years ago, with an advisory group known as the Smithsonian Latino Center, the predecessor of the NMAL. The NMAL will eventually have a building on the mall in Washington, D.C. Selene Preciado was contracted by the Smithsonian Latino Center to work on the show in 2016, and the invitation to collaborate with The Cheech was extended in 2020.

An exhibition catalog, with essays by Preciado and three other scholars, is forthcoming.

The national tour schedule of the Collidoscope exhibition is as follows: Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christi, TX (April 20 – September 30, 2023); The University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX (October 20, 2023 – January 7, 2024); Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, OK (February 3 – April 28, 2024); The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, NY (May 18, 2024 – January 5, 2025); Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA (February 7 – May 4, 2025); and The Mint Museum, Charlotte, NC (June 7 – September 21, 2025).

In San Antonio, the de la Torre brothers will also make an installation in the AT&T Lobby at the McNay Art Museum in September of 2023, and they will also have an exhibition at the McNay in February of 2024.

***

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian who has curated more than thirty exhibitions and who has written or contributed to nineteen catalogs and books.

1 comment

Great article about two of the leading artists in contemporary art! The De La Torre brothers are showing a new path in prolific creativity vibrating at a higher level. They have a masterful way of connecting and reinterpreting the major cultural icons of the Mexican diaspora. Their work is at the highest quality with a very full expression. Bravo for a great exhibition at The Cheech!!!