César A. Martínez is a trailblazer for Texas art. He was the first Chicano artist in the state to have a museum retrospective, in 1999, at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio. That exhibition brought together his works from the 1970s through the 1990s. His recently closed show at the Laredo Center for the Arts brought together mostly artworks he made after the McNay retrospective. Included in the show are four main series that Martínez has worked on consistently over the past years: the Pachuco or Bato series, the South Texas series, the Mestizo series, and the Serape series. While many of the works are reprisals of imagery he has worked on in the past, the works have key additions of foil collages and digital drawings the artist created with Autosketch, a 2D vector drawing program.

Installation view of “César A. Martínez: En Mi Casa” at the Laredo Center for the Arts. Photo by Liz Kim.

Walking through Martínez’s show in Laredo is like peeling an onion. In the large, unpartitioned gallery of the art center, double-sided modular wall panels have been arranged in five layers throughout the exhibition space. Each layer represents a different theme that uncovers various aspects of the artist’s identity and the Chicano culture he represents, from the brittle outer shell to the shapely spiral core in the center. In sum, the show is a journey through many elements that comprise Chicano identity.

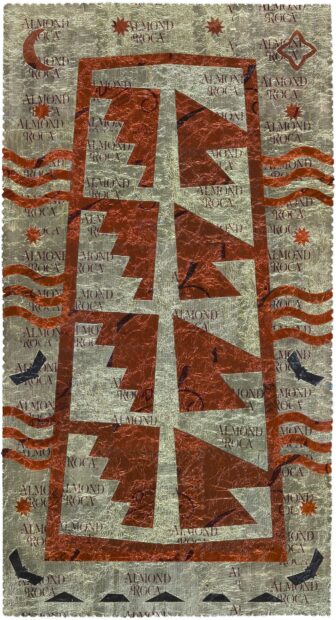

César A. Martínez, “Three Rivers Petroglyph,” 2015, Collage on paper, 14.5 x 8 in. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright César A. Martínez.

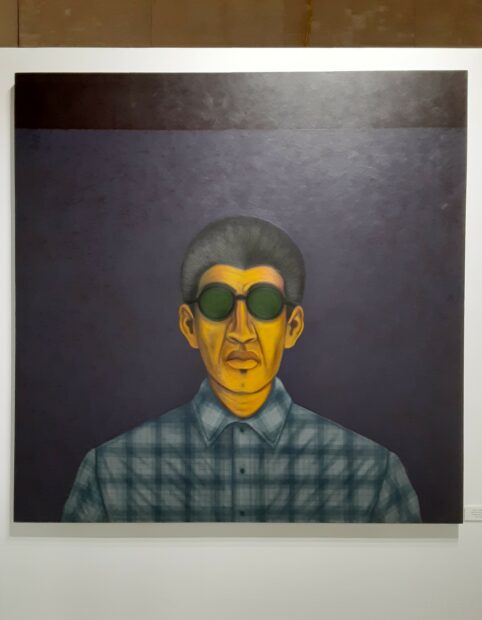

The first layer is an introduction to the artist. One of his signature, timeless, sunglass-wearing self-portraits is hung high on the wall, looking more aloof than usual. It is joined on either side by a pair of his foil collages, Three Rivers Petroglyph. Rivers gave birth to civilizations in the neolithic revolution, and Martínez’s works focus the premise of the show on the history of Chicanos. The foil collages, on closer inspection, are made of gold Almond Roca wrappers and copper foil from Dove peanut butter candies. The collages are precise and seamless, as though sculpted of actual metal sheets. They are made up of patterns after one of the petroglyphs from the Three Rivers site in New Mexico, attributed to the pre-Columbian Mogollon culture, who were indigenous to Chihuaha, Southern New Mexico, and West Texas. The original petroglyph is comprised of asymmetric repetitions of step-like triangular patterns that Martínez has encased in a rectangular border, like a stele. Behind this frame are three sets of wavy rivers that place this piece. The transformation of mundane found and collected materials into the historical and extraordinary — distinct from the messy repurposing of everyday objects in Pop art — is a theme found throughout the show.

César A. Martínez, “El Shorty,” 2016/2021, Acrylic on canvas, 54 x 54 in. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright César A. Martínez.

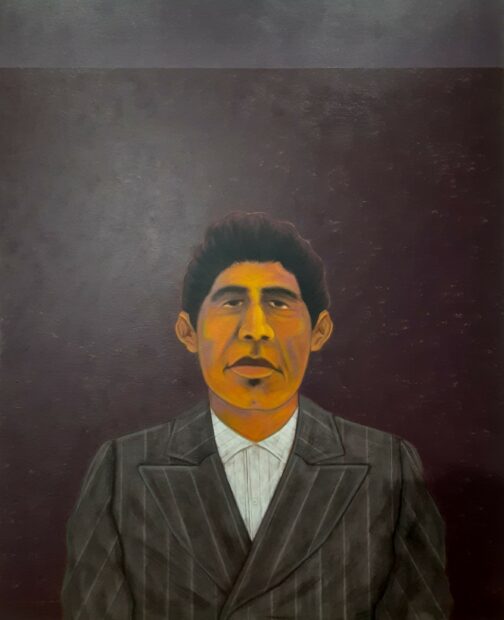

The next layer deals with Pachucos (also known as the “zoot-suiters.”), the Mexican American countercultural movement active from the 1930s through the 1950s. These characters are the brittle outer layer of the onion, and they stare you down with slight curls at the corners of their lips: fake smiles. There are a pair of these works, Shorty and Veterano, both derived from earlier iterations of Martínez’s characters. Typical to Martínez, they both are in a frontal, half-length portrait format that shows influences from Richard Avedon and Fritz Scholder, according to the catalog from Martínez’s McNay exhibition. Shorty’s skin is a sickly orange, with iridescent contours rendered in purple and green paint, and he pushes back at the viewer with his slow, downward gaze. His suit is striped charcoal and paired with a white vertically striped shirt. Martínez’s approach to the suit is post-minimal, compared to his earlier iterations of Pachuco characters, which are more influenced by the expressionistic strokes of color-field paintings. This signals a shift in Martínez’s practice over the past decades. His turn toward post-minimalism is also indicated by the hardened edge of the complementary color band typically found at the top of Martínez’s figurative paintings. This color band is also used differently in these later works: the band is generally thinner than before, with a larger gap between it and the top of the figure. The overall effect is that the figures seem slightly compressed and less imposing, while the tension in the space between the figure and the top band is increased. In this particular work, the deep burgundy background is reminiscent of bruises, another detail that seems to push the viewer away.

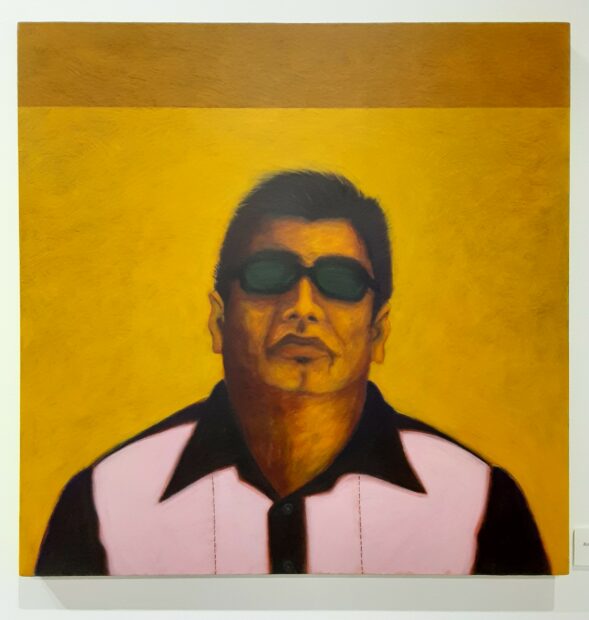

César A. Martínez, “Bato Con Pink and Black Shirt,” 2009, Acrylic on muslin, 28 x 28 in. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright César A. Martínez.

As the exhibition peels the next layer from its protective skin, Martínez’s subject matter becomes much lighter and deals with the idea of play. This layer is also defined through a figurative pair in the Pachuco or Bato series, but rather than the menacing burgundy, the background color here is yellow. In one of these works, Bato Con Pink and Black Shirt, the figure is almost impressionistic, with brushstrokes that are breezy and sunny. Although the figure is wearing sunglasses and tilting his chin slightly upward, the gesture is one of welcome. This dude has taken his suit off to relax, and is allowing us to continue peeling back the layers of identity that make up Texas Chicano culture.

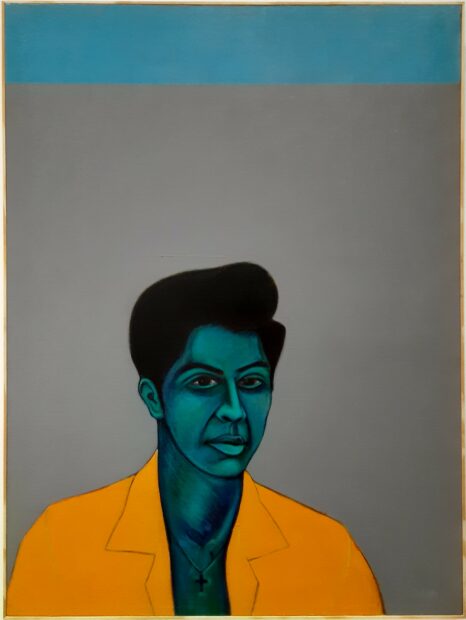

César A. Martínez, “Balta,” 1978/2015, Acrylic on canvas, 48 x 36 in. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright César A. Martínez.

The next layer is love, defined by a pair of figures, Balta and La Perla, representing two biological genders. The gentleman, Balta, is electric in his rich greenish blue skin. There’s a deep affinity to Picasso in this work in the way that Martínez wrangles with 2D form, but this figure is also sculpted, with elegant curving shapes that signal longing and energy. The figure wears a canary yellow suit jacket that complements his turquoise tone, and the backdrop is a flat, even gray that subtly shifts with the texture of the canvas itself.

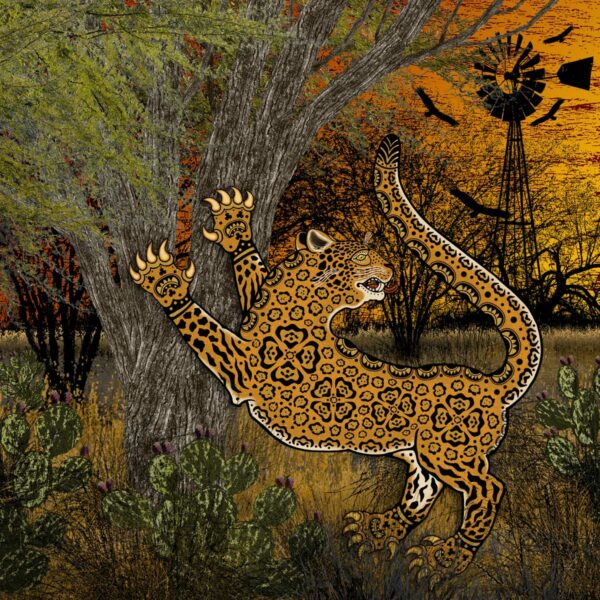

César A. Martínez, “Huizache Jaguar,” 2021, Digital dimension print, 18 x 18 in. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright César A. Martínez.

The last modular layer for the viewer as they walk through the show is a digital painting of a jaguar in a South Texas landscape, which is dotted with a Texas windmill, huizache trees, brush, nopales, and vultures circling the sky. The jaguar is highly stylized, from the Mexican folk tradition, and it looks away startled while in the midst of scratching its claws onto the huizache’s bark. The combination of this animal imagery, which for Martínez has symbolized the ancient Americas, with a South Texas landscape, signals the show’s turn toward environment and history.

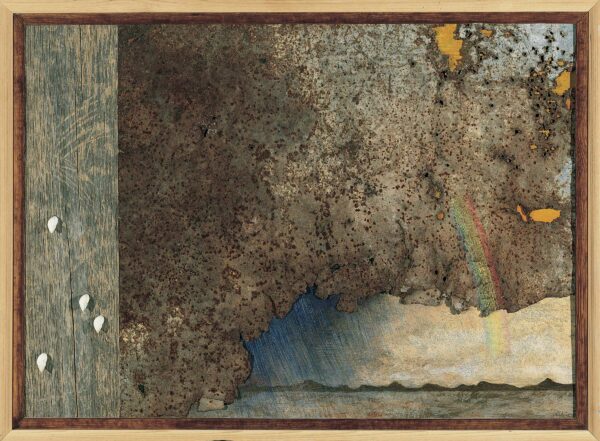

César A. Martínez, “Parece Que Viene Agua,” 1992, Mixed media on wood and metal, 25 x 34 in. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright César A. Martínez.

Along the back wall of the art center are works in various media, ranging from monotypes in the artist’s South Texas series, and his later foil collage series. Martínez’s South Texas series can be divided into mixed media constructions and his Sol y Remolino mixed media paintings. Parece Que Viene Agua, which was shown in the 1999 McNay retrospective, introduces us to how the South Texas landscape, as well as the region’s seascape, influences the artist’s work. A rusted metal sheet dotted with aged cracks and punctures covers a majority of the composition. This represents the salty atmosphere of this region of the Gulf of Mexico, which brings rust to any nearby unprotected metal surface. The small gaps on this metal sheet open up into a wooden backing painted with an orange sky. In the bottom right hand corner of the work, a seascape with an outgoing curtain of rain leaves a band of pastel rainbow across the painted wood and the corrupted metal. On the left edge of the composition is a plank of weathered, solid wood, on which white shells of caracoles (a land snail variety local to South Texas) have been placed. According to the artist, “ranch lore has it that they climb bushes and walls when they sense that rain is coming.” The entire composition is expressive of both the salty air of South Texas that fills the lungs on each breath, and of the connection between land and sea.

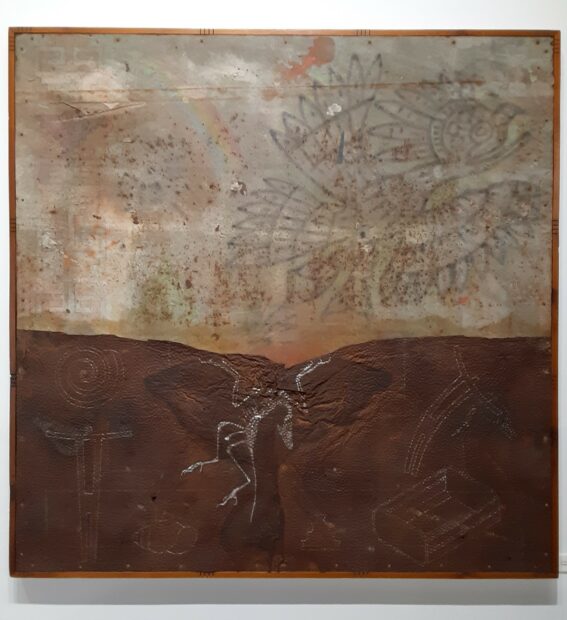

César A. Martínez, “At Play in the Fields of Cesar Chavez,” 2017, Mixed media on metal and wood, 64 x 64 in. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright César A. Martínez.

At Play in the Fields of Cesar Chavez is composed of two rusted metal sheets. The top half is painted with a powder coating, and fine lines and cracks appear on the surface. It has subtle shifts of color, ranging from harvest yellow to shell pink. The bottom half, which is brown from rust, features round indentations that appear to have been made by a hammer. Drawn onto this rusted surface in white outlines are images of various petroglyphs found near Del Rio, including a version of the White Shaman from the White Shaman Preserve in Comstock, Texas. A dark outline of a bird has also been sketched in the middle of this sheet; the position of the bird makes it look as though it is flying up into this sculpture’s fissure. Another bird has been lightly drawn onto the work’s top area (this time taking after a Mayan design), rising into the air with its beak facing upwards. The overall meaning of the bird, in Mesoamerican symbology, is one of transformation, arising from the prehistoric earth and launching into the skies. It is an allusion to the political movement of Chicano identity that Cesar Chavez established.

César A. Martínez, “Sol y Remolino,” 2017, Acrylic and mixed media on paper, 22 x 22 in. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright César A. Martínez.

Also on the back wall is a work from Martínez’s ongoing Sol y Remolino series. These works are mixed media paintings that incorporate dried plants from South Texas’ ecosystem. This work is about power. In the piece on view, power comes from the sun, here expressed as a multicolored circle that radiates from the center of the square painting’s surface, which gives energy to life at the cellular level. Thin splashes of purple shoot violently out of the earth, which is represented by a short brown band at the bottom part of the painting. This series helps explain the color and thematic foundations of Martínez’s figurative paintings: the burgundy and bright yellow of his Pachuco series originates from this elemental combination between the forces of the earth and the sun.

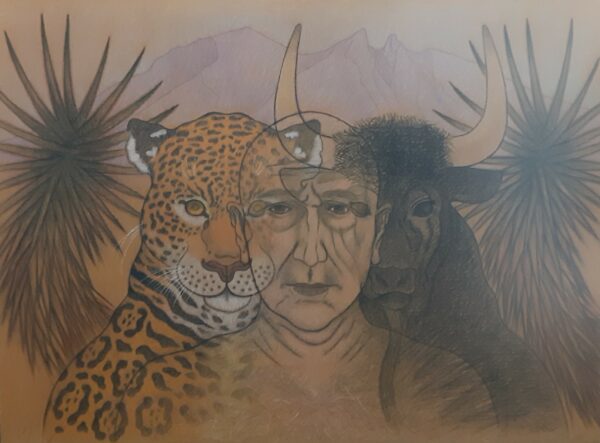

César A. Martínez, “El Mestizo,” 2016, Mixed drawing media on corrugated cardboard, 30 x 40 in. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright César A. Martínez.

As the viewer returns toward the entrance, they see the other side of the exhibition’s wall partitions, also in layers. On the reverse of one wall, the theme of mixture is dealt with from a cultural perspective, with a newer work from the artist’s Mestizo series. The work is immaculately drawn; admiring the piece closely reveals that it’s executed on corrugated cardboard, perhaps the most mundane and easily discarded material on Earth. Martínez uses its lined texture to create an illustration or print-like feel. An older, central figure is superimposed on either side by a jaguar and a bull, which for Martínez symbolizes the ancient Americas and Europe, respectively. Unlike the self-portraits of the Bato series, where he never ages, this work is drawn directly from how Martínez looks now. With this work, Martínez reaffirms his mixed Mestizo heritage in the present, in the naked center of the exhibition, as the viewer is compelled outward into the rest of the show to deal with varying cultural and historical aspects of what it means to be Chicano.

César A. Martínez, “Bato Con Sunglasses,” 2014, Acrylic on canvas, 64 x 64 in. Photo by Liz Kim. Copyright César A. Martínez.

Laredo, Texas is going through big changes. The city’s recently established a Cultural District in its downtown; Maritza Bautista has created a new artists’ residency program, Cultivarte, and is in the midst of finding a permanent home, which will include artists’ studios and an exhibition space. And the Laredo Center for the Arts is starting a permanent collection to preserve the legacy of artists with roots in the city.

This reemergence is important because the pandemic devastated the city’s downtown. During lunchtime, I couldn’t find a single restaurant open within walking distance of the Center, which is located near the middle of the downtown grid (I found out later that one restaurant was open, but it had no visible signage). According to artist Gil Rocha, who’s native to Laredo, the cross-cultural border traffic was shut down during the pandemic. This had a disastrous economic impact on the city, as it had previously depended a great deal on Mexican consumers crossing the border from Nuevo Laredo. The border reopened just two months ago, bringing back some of the pre-pandemic activities. This open exchange of cultures between the U.S. and Mexico sides defines Laredo, and with the city starting to rev back, the Center is showcasing Martínez, an artist that encapsulates this cross-cultural experience and identity.

Overall, Martínez’s show is a testament to the multitude of layers that make up Chicano identity, informed through his upbringing between U.S. and Mexican cultures in Laredo, and revealed through the visitor’s journey across the exhibition hall. The show’s opening was a huge celebration, with the Mayor giving Martínez the key to the city and a welcome by the City Council members. With everything Martínez brings to Laredo, and in a larger sense, Texas’ border with Mexico, it is only fitting that he was given the homecoming he deserves.

César A. Martínez: En Mi Casa was on view at the Laredo Center for the Arts from November 19, 2021 through January 14, 2022.

1 comment

In the 90’s I once found and purchased a print of Martinez’s vato paintings at a flea market. I didn’t know him but I saw Martinez at an opening and told him about my recent find and he really got a kick out of it. You know you’ve really made a successful art career when your works can be found at an open air flea market in San Antonio(i paid $10 for it).