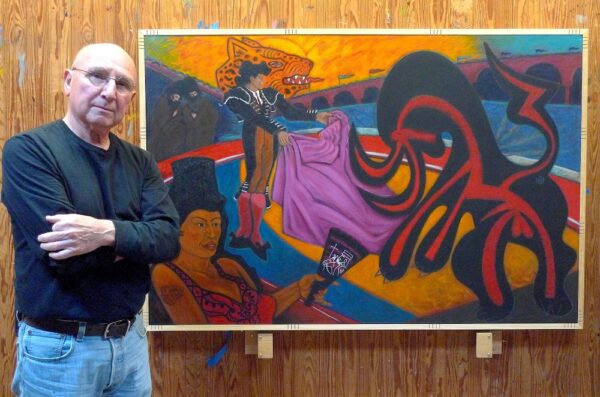

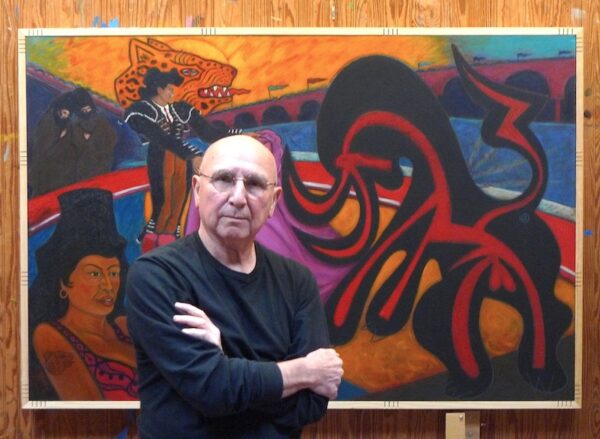

Cesar Martinez in his studio with Toreando El Toro de Picasso with La Malinche, Como “Carmen,” Watching (Messing with Picasso’s Bull with La Malinche, as ‘Carmen,’ Watching), 1988, partially altered 2019, acrylic on canvas, 40 x 60 inches, collection of the artist, photograph by Ruben C. Cordova, 2019

The indigenous person known as La Malinche (c. 1502 – c. 1528?) is one of the most controversial historical figures from the period of the Spanish conquest of Mexico. She is reviled by some, including the influential Nobel Laureate Octavio Paz, who posits her as the symbol of betrayal at the heart of Mexican national history and consciousness. She is defended and celebrated by others, including Chicana feminists, who repudiate Paz’s masculinist interpretation. Many laud her as a survivor and some even view her as a powerful, saint-like intercessor for her people.

La Malinche has long fascinated the San Antonio-based artist Cesar Martinez. This article discusses the series of works in which Martinez hybridizes La Malinche with the Roma seductress who was the title character of Georges Bizet’s opera Carmen (1875), which is set in Spain. Martinez, who has a deep interest in bullfighting, references Picasso and Goya, and he inserts jaguar imagery as an emblem of the Americas in the painting illustrated above that was his initial foray on this theme. His subsequent monotypes and digital prints center on the head of his Malinche/Carmen composite, combined with bull imagery, pyramids, and other symbols.

Malinche in Myth and History

Matthew Restall, in When Montezuma Met Cortes (2018), notes the invention of three literary Malinches. The first was in the nineteenth century, when she was presented as a sanitized, “ideal woman,” an intelligent beauty of noble birth endowed with affection, loyalty, good temper, and good manners. She was praised for being an enthusiastic Christian convert and a docile and deferential wife to her “husband” Cortés. Some authors even had Cortés and Malinche spout absurd love poetry at one another. The conquest was represented as an international romance. But Cortés and Malinche never married, and there is no evidence of any great romance between them. Cortés already had a wife, Catalina Juárez, who came to Mexico from Cuba around the time Malinche gave birth to their son Martín, who Cortés later took to Spain. Unlike Cortés’ Taíno paramour Leonor, Malinche is not mentioned in his will. Restall emphasizes that “in the 1520s, ‘Indians’ were Spanish possessions, to be commanded or killed, to be given away or sold, kept or impregnated, as their ‘owners’ wished.” Contrary to many later rationalizations, Malinche and her companions were likely given to serve as sex slaves. Historically, Cortés initially gave Malinche to Alonso Hernández de Puertocarrero, who returned her after he was sent to Spain. Cortés shared her with Gerónimo Aguilar (some soldiers thought she was married to Aguilar). After the conquest, Cortés gave Malinche to Juan Jaramillo, who she married, and she subsequently disappeared from the historical record.

Martinez notes that La Malinche is often despised in Mexico for the assistance she gave to Hernando Cortés during the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs. Restall says the interpretation of Malinche as a “conniving traitor” also appeared in the nineteenth century, primarily as a reaction against the idealized Malinche. By the early twentieth century, the neologism malinchista became synonymous with traitor. The most dramatic expression of this point of view is found in Paz’s Labyrinth of Solitude (1961). Paz contrasts Malinche and Cuauhtémoc, the Aztec emperor who led the final resistance against the Spanish:

If the Chingada [the fucked one] is a representation of the violated Mother, it is appropriate to associate her with the Conquest, which was also a violation, not only in the historical sense, but also in the very flesh of the Indian woman … the Mexican people have not forgiven La Malinche for her betrayal. She embodies the open, the chingado, to our closed, stoic, impassive Indians. Cuauhtémoc and Doña Marina are thus two antagonistic and complementary figures … This explains the success of the contemptuous adjective malinchista recently put into circulation by newspapers to denounce all those that are corrupted by foreign influences. The malinchistas are those who want Mexico to open itself to the outside world: the true sons of La Malinche, who is the Chingada in person.

As noted by Carrie C. Chorba in Mexico, From Mestizo to Multicultural (2007), Paz’s work fits within a larger end-of-the-millennium anxiety pertaining to national identity. Chobra cites Carlos Fuentes to point out the problematic nature of Paz’s conquest-as-rape paradigm: “From whence comes the legitimacy of a country when it denies its father, the Spanish rapist, and condemns its mother, the indigenous traitor?” In The Secret History of Gender (1995), Steve J. Stern argues that the Malinche narrative conjoined themes of female violation and female treachery “into the image of woman’s deserved violation.” Emma Perez crafts a powerful psychoanalytic take-down of Paz in “El Chingón [The Fucker]: Octavio Paz and the Oedipal-Conquest-Complex” (1991; see excerpt here). She begins with Gloria Anzaldúa’s insight from Borderlands/La Frontera: “The worst kind of betrayal lies in making us believe that the Indian woman in US is the betrayer.” Perez argues that Paz’s “Oedipal-conquest-triangle” lays the groundwork for “sexual, political, social, and psychological violence against la India” because women are misogynistically posited as eternal betrayers and eternal whores. Moreover, men like Paz have inferiority complexes vis-á-vis the symbolic white father/conqueror. These are consequences of imposing “the psychodrama of conquest upon the Chicano.”

Restall’s third literary Malinche is the creation of late twentieth-century feminists. In Infinite Divisions: An Anthology of Chicana Literature (1993), Tey Diana Rebolledo and Eliana S. Rivero note that many Chicana writers identify with Malinche as a survivor of extremely difficult circumstances. They admire Malinche’s skill with language, as well as the “political intuition” that led her to side with the Spaniards “in order to ensure the survival of her race.” Consequently, she “lives on in every Chicana today.” Furthermore, despite an indigenous death toll that has been estimated as high as 100 million, they argue that Malinche’s diplomacy prevented “a more total annihilation” of indigenous peoples. Thus, in her “capacity as intercessor and helper,” Rebolledo and Rivero argue that La Malinche “takes on the attributes of the Virgin of Guadalupe.”

Rafaela G. Castro, in Chicano Folklore (2001), sees Malinche as embodying “the survivalist psyche of the Chicana.” Castro says Malinche was defamed in the same manner that Chicanas are denigrated: her “victimization and criminalization” is a “double oppression” comparable to what Chicanas and Mexicanas suffer. Castro — even more emphatically than Rebolledo and Rivero — says “there is no doubt” Malinche is “a heroine, almost on the same plane as La Virgin de Guadalupe.” Thus the person that Paz characterized as the lowest traitor has been elevated into a heroine of the highest rank and importance: in this view she is nothing less than a savior figure and a second mother of Mexico.

Alicia Gaspar de Alba draws heavily on Perez in a chapter called “Malinche’s Revenge” in [Un]Framing the “Bad Woman” (2014). She notes that Chicana feminists are transforming the Malinche story into an image of Chicana “resistance against female slavery to patriarchy.” Gaspar de Alba points out that what were formerly seen as negative qualities are turned into positive affirmations: a woman can use her mind, speech, and body to “cultivate her intellectual skills for her own survival and empowerment.” A website by the University of Oregon called “La Malinche: From Whore/Traitor to Mother/Goddess” features a variety of visual images and literary excerpts about Malinche.

Let’s take a closer look at the historical Malinche. “She was a slave,” Martinez told me in 2004, “and she — like entire tribes — didn’t owe the Aztecs any favors.” Gaspar de Alba (in the book chapter cited above) and Eduardo Matos Moctezuma (in Arqueología Mexicana, 2020) reach the same conclusion.

La Malinche was the daughter of a cacique (chief). Her father died and her mother remarried another cacique. Malinche was sold into slavery so that her younger half-brother could become the legitimate heir to the property of both of her mother’s husbands. After the Spanish defeated the Tabascans, she was given to Cortés along with nineteen other young women and other gifts, variously described as chickens, fruit, cloth, and small gold objects. La Malinche, who knew Yucatec Maya and Nahuatl (the language of the Aztecs) initially translated in conjunction with a man who knew Maya and Spanish. She also learned Spanish. From the beginning, historians have credited her with serving Cortés as a strategist as well as a translator. Jon Mancip White, in his Cortés and the Downfall of the Aztec Empire (1971) says she quickly became “indispensable to Cortés.” She could converse with the Tabascans, the Coatzacoalcans, the Mayas, the Aztecs (and other Nahau speakers). White adds:

It is clear that she was much more than a simple interpreter. Cortés consulted her on matters of general policy and on all matters relating to Indian psychology, and both Díaz and Gómora [Conquistador historians] accord her a whole section to herself in their respective accounts. Her contribution to the Conquest was acknowledged by the Mexicans of her own time and by later generations.

Malinche and Cortés were always together during negotiations, resulting in confusion regarding their proper names. Accounts differ substantially, but according to Restall, the woman’s original Nahua name is unknown. The Spanish called her Marina and added the honorific doña prefix because she quickly achieved high status. The Aztecs and other Nahua used Malintzin, their version of Doña Marina (tzin is an honorific, akin to doña). Malinche is a Hispanicized version of Malintzin.

Gloria Anzaldúa, writing in Borderlands: La Frontera (1987), makes the historically untenable claim that the Aztec elites were “so unpopular with their own common people that they could not even mobilize the populace to defend the city.” She makes this claim in order to minimize Malinche’s role in the conquest: “Thus the Aztec nation fell not because Malinali (la Chingada) interpreted for and slept with Cortés, but because the ruling elite had subverted the solidarity between men and women and between noble and commoner.” Even if one does not agree with Alfred Percival Maudslay (translater of Bernal Díaz del Castillo’s The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico, 1517-1521; 1956) that the Aztecs’ “courage and endurance during the last days of the siege of Mexico is unrivalled,” the Aztecs mounted a remarkably valiant defense, especially considering that they were also combating medical epidemics for which they had no immunity. Nonetheless, Restall argues that the entire traditional account of the Spanish “conquest” (repeated endlessly by historians) is preposterously wrong. He instead sees an epic war between the Aztec alliance and the Tlaxcallan alliance, with the Spanish as very minor partners of the latter. After the wholesale destruction caused by disease and the imposition of European-style total war, the Spanish eventually emerged triumphant. If — as Restall argues — the Spanish had little agency and their role in the war was not very significant, then Malinche’s assistance to the Spanish could not have been very significant either.

Martinez’s Toreando El Toro de Picasso with La Malinche, Como “Carmen,” Watching

Cesar Martinez, training with a young heifer at the Santa Maria Bullring, near Santa Elena, Texas, 2013, photograph courtesy of the artist

For much of his life, starting at the age of 14, Martinez was obsessed with bullfighting. He wanted to become a bullfighter, and he trained with professional bullfighters in Nuevo Laredo who practiced with heifers — young, female fighting stock — during tientas, the testing of the young females for breeding purposes. Martinez never became a professional bullfighter, and he never killed a bull (so the rumors that he paid for his undergraduate tuition with money earned from bullfighting are hereby debunked). In his earlier days Martinez was transported by the romance of the art of bullfighting, and he turned a blind eye to its cruelties, though they did disturb him.

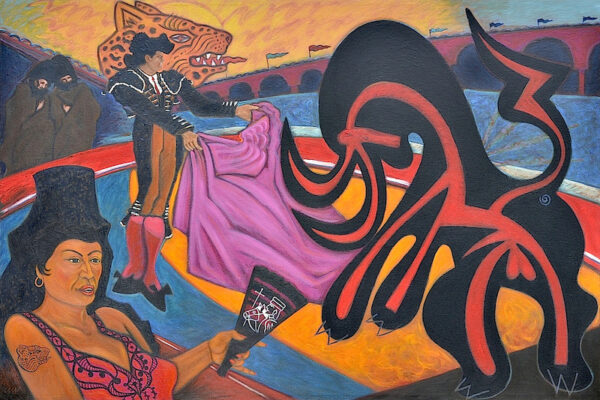

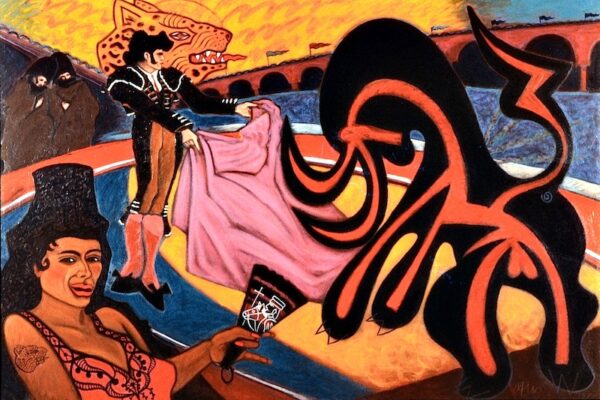

Cesar Martinez, Toreando El Toro de Picasso with La Malinche, Como “Carmen,”Watching (“Messing with Picasso’s Bull with La Malinche, as ‘Carmen,’ Watching”), 1988, acrylic on canvas, 40 x 60 inches, collection of the artist, photograph courtesy of the artist

Toreando El Toro de Picasso with La Malinche, Como “Carmen,” Watching is, above all, a bullfighting painting. It references the two greatest Spanish painters who were obsessed with bullfighting: Francisco Goya and Pablo Picasso.

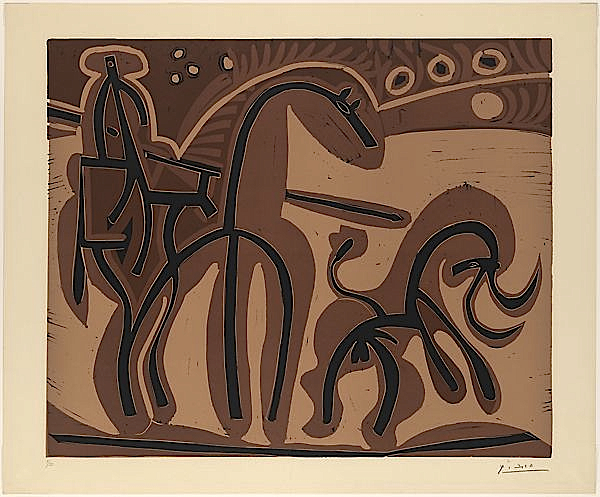

Pablo Picasso, Picador and Bull, 1959, linoleum cut, 20 7/8 x 25 ¼ inches (block), Metropolitan Museum of Art

Martinez’s bull closely follows one Picasso created in 1959, though Martinez transformed it: he reversed it, changed its color scheme, and monumentalized it. His bull appears to be charging rather than retreating, the red and black colors emphasize mortality, and its size makes it seem particularly dangerous.

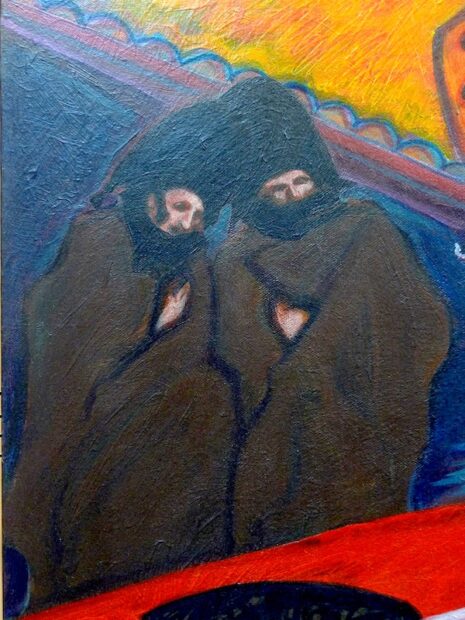

The two figures in brown cloaks behind the bullfighter in Martinez’s painting are taken from the Metropolitan Museum’s Majas on a Balcony, now recognized as a variant of the prime Goya painting in the Rothschild collection.

Attributed to Francisco Goya, Majas on a Balcony, c. 1800-10, oil on canvas, 76 ¾ x 49 ½ inches, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cesar Martinez, Toreando El Toro de Picasso…. (detail of two men in left background), photograph by Ruben C. Cordova

Martinez has drawn the two men together in conspiratorial proximity. Though the artist had initially imagined the two men as Spanish, Martinez created a fluid, fantastical scenario with characters from different eras that is open to conflicting interpretations, even on his own part. After some discussion of the identity of the two men, Martinez said that they “could be malinchistas speaking ill of the Malinche/Carmen character.” He pointed out that both Malinche and Carmen were lightning rods for social disapprobation. After further reflection, he said in jest that one of the men could be Octavio Paz, since he was the dominant, negative male voice in contemporary discussions of the subject. Though I had assumed the setting was contemporary Spain, Martinez explained that the painting was not situated in a fixed historical period or a specific geographical location: “it could be Mexico, Spain, Bogotá, or anywhere else in the bullfighting world.” While witnessing an act of high drama, potentially removed from Mexico and/or Spain, these two men cannot refrain from bad-mouthing Malinche/Carmen.

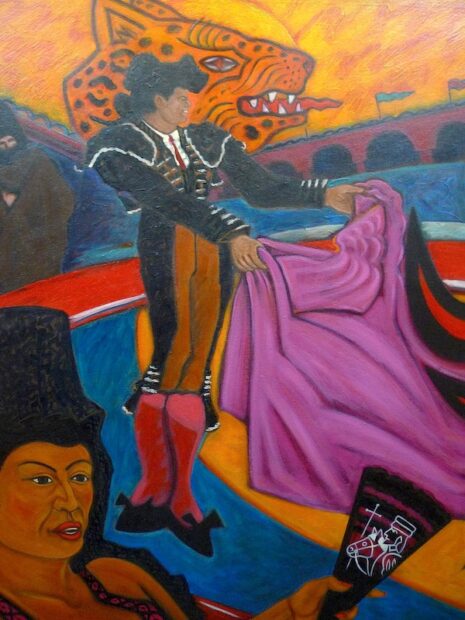

Cesar Martinez, Toreando El Toro de Picasso…. (detail of bullfighter and Malinche-as-Carmen), photograph by Ruben C. Cordova

Martinez says the Mexican matador Fermin Espinosa, known as “Armillita” (b.1911) is the greatest of all time. He had him in mind when he made this painting. Martinez compares the bullfighter’s technical mastery to that of boxer Muhammed Ali. “Fermin could handle any type of bull with poise,” says the artist, “and he had an extensive repertoire that few have ever had. He also placed his own banderillas with distinction. Fermin was referred to as el maestro de maestros (the master of masters, the teacher of teachers) and he is as revered in Spain as he is in Mexico.” Martinez emulated another type of bullfighter when he was fighting bulls, one that emphasized emotion to “structure the performance and elevate it to the level of a work of art, like a symphony.”

Martinez did not render a portrait of Armillita. Rather, it is a stylization of a Picasso-type of torero, partially merged with a likeness of Armillita. Martinez thought the heads of the bullfighter and Malinche-as-Carmen were “too cartoonish” in the original state of the painting, so he repainted them in 2019. He still doesn’t think the bullfighter looks very much like Armillita because his intentional distortions mitigate against an accurate portrayal.

Martinez was also aware of political inequities in Spanish bullfighting: Mexican bullfighters were paid less than Spanish bullfighters, which caused the Spanish bullfighter’s union to oppose Mexican bullfighters. The Spanish aficionados loved the Mexican bullfighters says Martinez, because they did things “a bit differently, with class, art, and a special something that Spaniards call ‘duende’ (magic).”

Cesar Martinez, Toreando El Toro de Picasso… (original state of the painting), photograph courtesy of the artist.

The stylized legs of the matador are a recollection of an artwork (probably by an artist influenced by Picasso) that was reproduced in the first book on bullfighting that Martínez saw when he was a child. The jaguar head in the background points to Armillita’s Mexican origin.

Cesar Martinez, Toreando El Toro de Picasso…. (detail of Malinche-as-Carmen’s hand and fan), photograph by Ruben C. Cordova

Martinez reworked Malinche-as-Carmen’s left hand: in Carmen-like fashion, she is making a provocative “cuernos” (horned) gesture, which, in Mediterranean and Latin countries means cuckold (this might be news at UT Austin, where sports fans make this gesture and chant “hook’em horns”).

Cesar Martinez, Toreando El Toro de Picasso…. (detail of Malinche-as-Carmen), photograph by Ruben C. Cordova

When he made this painting, Martinez imagined Malinche as “a smart, free-spirited woman who thought for herself … I likened her to the title character of the opera Carmen by Bizet.” Carmen was a Roma (gypsy), and she, like Malinche, had to make her own way outside of the norms of the society in which she lived. The historical Malinche did not possess personal agency: she was gifted from Spanish man to Spanish man, and she had no element of choice in these bodily transactions, though Martinez views her as a born survivor who makes the best of her situations. Carmen, on the other hand, possessed the personal agency that Malinche lacked. Most importantly, Carmen refused to be the permanent — or even the long-term — possession of any man. She was the defiant antithesis of Malinche: when her spurned ex-lover Don José approached her, she knew he would kill her if she refused to go with him, but she defiantly declared that she was born free and that she would die free. While the crowd cheered for Carmen’s current lover, the bullfighter Escamillo, the jealous Don José murdered Carmen at the entrance to the bullring. Carmen’s freedom was paid for with her life. Women, therefore, are subject to a damned-if-you-do (Malinche), damned-if-you-don’t (Carmen) dilemma.

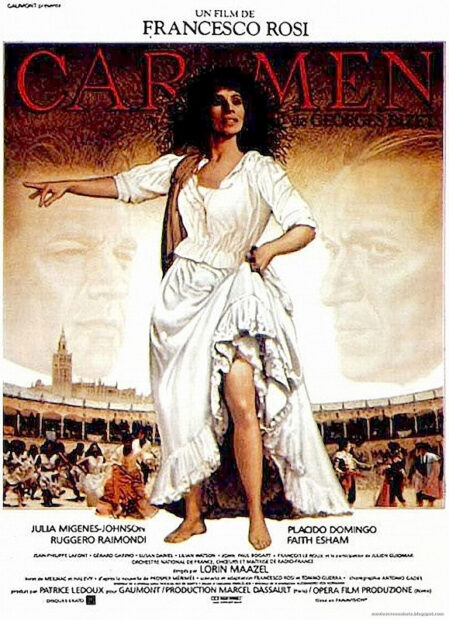

Martinez is more a bullfighting aficionado than an opera buff (though his cultural interests include opera, classical music, blues, and flamenco), so it is understandable that, of all possible operas, he gravitated to Carmen. He also valued the music and the narrative. Initially reviled because it dealt with lower-class people and illicit behavior, the opera has become one of the most popular in the classical canon, with performances by some of opera’s greatest stars including Maria Callas and Jessye Norman. Martinez has seen many opera productions of Carmen, but his initial exposure to the work was via two great — and very different — films made in the 1980s. Carlos Saura’s fast-paced, kinetic 1983 production is a film within a flamenco stage show. Franceso Rosi’s sweeping 1984 epic starring Plácido Domingo featured such picturesque locales that critic Roger Ebert dubbed it “the Raiders of the Lost Ark of opera films.”

Bizet’s Carmen was a maja, someone from the lower classes who dressed in flamboyant Spanish costumes, often with a fan in one hand, whereas upper-class women imitated French couture. Malinche-as-Carmen is seated in a bullring; Martinez views the bullring as a kind of battleground where his “fanciful notions play out.” He also sees it as a “metaphoric arena for the Conquest of Mexico.” But here the premier Mexican bullfighter is testing himself against a premier Spanish bull, one “bred” by the premier painter Picasso. Malinche-as-Carmen wears a traditional black Spanish mantilla, and she has a black fan, which bears the image of Cortés. Martínez explains that he meant this image to be dismissive, that Cortés had become “an asterisk,” a mere “detail” now stamped on an accessory like any sundry, bygone memento. Carmen-as-Malinche is darker than a Spaniard because she is meant to be fully indigenous. That point is emphasized by the jaguar head tattoo on her right arm, which echoes the one behind Armillita.

Carmen’s costume in Rosi’s film appears to have influenced Malinche-as-Carmen’s outfit, though the latter’s jacketless, tight-fitting dress is more risqué, and rather at odds with her traditional high-rise mantilla.

Monotypes of Malinche/Carmen

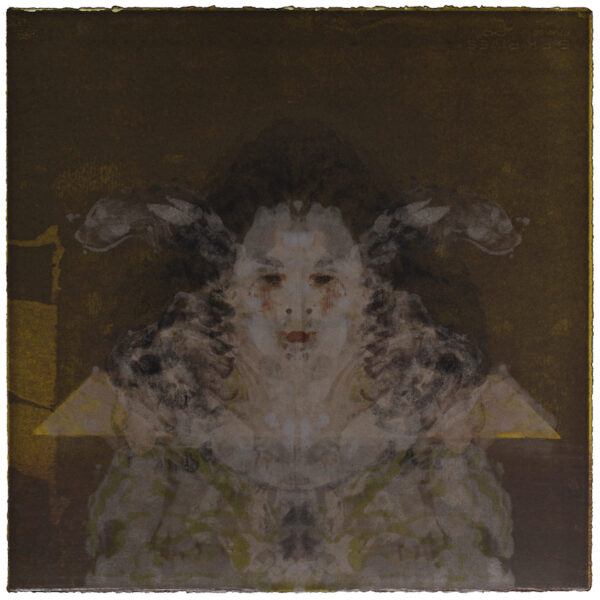

Cesar Martinez, Artpace Monotype #19, 1997, 22 x 22 inches, collection of the artist, photograph courtesy of the artist

Martinez and his master printer Peter Webb created an extensive monotype project when Martinez received an Artpace San Antonio residency in 1997. They produced more than 70 monotypes, 22 of which were exhibited. Martinez gradually layered multiple forms on one another. At some point, as he was “riffing” on these compositions, which he characterizes as “a very jazzy experience,” Martinez realized that his forms resembled a Malinche/Carmen synthesis. Most of these images have forms that suggest one or more pyramids and bull’s horns. ArtPace Monotype #19, pictured above, has forms projecting from the side of her head that suggest snakes. Forms on either side of her head resemble skulls.

Cesar Martinez, Artpace Monotype #45, 1997, 22 x 22 inches, collection of the artist, photograph courtesy of the artist

The figure in ArtPace Monotype #45 seems to have bushy eyebrows and a moustache, as well as a suit of armor, so one could easily read it as male. The bullhorns are as stylized as an Islamic crescent moon, and the ghostly gold pyramid at the top echoes a silver one below.

Digital Images of Malinche as Carmen

Cesar Martinez, La Malinche As Carmen, 2004, Digital Dimension Print, 22 x 22 inches, collection of the artist, photograph courtesy of the artist

Martinez made digital prints for a Lyric Opera of S.A. benefit in 2004, in conjunction with an event called “Dances With Bulls” (the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio has in its collection, among a number of works by Martinez, one of these prints). It consists of a bloodless bullfight at the local Charro (Mexican rodeo) ring, where opera singers performed parts from Carmen. Martinez met Fred Renk at this event. He subsequently participated in tientas at Renk’s bull ranch in South Texas and, through Renk’s introduction, at Mexican bull ranches.

Martinez likes working with computer programs because they enable him to control even minute details, including forms, patterns, colors, tones, and the relationships between the individual parts. His monotypes are — by their very nature — experiments that are only partially controllable. Computer technology permits the artist to synthesize previous work with precision — including happy accidents — and to reproduce, alter, and transform them with remarkable levels of control. Malinche as Carmen is a composite extracted from the Artpace monotypes and combined with other manipulated and designed elements. Martinez is also able to retain accidental effects created in the monotype process, such as the four small heads of Emiliano Zapata that he found on the fringes of the woman’s hair (beside her eyes and neck). The hair itself has the appearance of being intermingled with black lace. Martinez’s hybrid image depicts Malinche as Carmen in ornate period Spanish garb. She also has an impressive head of (non-indigenous) curly hair, reminiscent of that on Rosi’s poster.

Cesar Martinez, La Malinche As Carmen with Logo, 2004, Digital Dimension Print, 22 x 22 inches, collection of the artist, photograph courtesy of the artist

The enormous bull horns that frame Malinche/Carmen can be interpreted as symbols of Spanish might — or of her destiny to suffer a violent death in a bullring, like the bull itself. The linear pyramidal base inscribed in gold decisively articulates an indigenous, stepped pyramid, rather than the generic triangular ones depicted in the monotypes.

Both the temple pyramid and the bullring are, functionally speaking, ritual theaters of blood. Circumscribed by these opposing forces, Malinche/Carmen’s body is as much of a battleground as is the bullring she inhabits. Her fancy filigree gown is a token of high status: “Malinche became quite a respectable lady,” notes Martinez. According to Jon Mancip White, Malinche was the first Mexican to become a Christian. He points out that her name “is never written in the records” without the respectful honorific Doña, an indication that she “was regarded as a person of consequence.” So while Malinche was passed around like a sex slave, she was — at least on paper, and at least while she was in the presence of Cortés — addressed as a “lady,” a person of status in Spanish society. In the digital prints Spanish qualities predominate: the luxuriant curly hair, the fancy gown, the blanched, extremely pale complexion (also taken from the monotypes). We are given a view of the arched, columned structure, filled with ghostly spectators. One can clearly make out the blood-orange curved wall of the bullring, and even the section number 4. That color is echoed by streams that emanate from Carmen’s eyes and mouth, which suggest blood (these too, were accidental effects produced in the monotypes). The title is also inscribed in blood-orange, fittingly enough, for a story that, on more than one level, is writ in blood.

Cesar Martinez in his studio with Toreando El Toro de Picasso with La Malinche, Como “Carmen,” Watching (Messing with Picasso’s Bull with La Malinche, as “Carmen,” Watching), 1988, partially altered 2019, acrylic on canvas, 40 x 60 inches, collection of the artist, photograph by Ruben C. Cordova, 2019

****

This article derives from a text written on the Carmen as Malinche digital print in 2004 for an exhibition Cordova curated at the Centro Aztlán. Reviewers have highlighted Martinez’s work in two of Cordova’s recent exhibitions: in Artsy on the Alamo at the Guadalupe in 2018, and in Rivard Report on Day of the Dead at Centro de Artes in 2019-20. (All three venues are in San Antonio). Cordova wrote the catalogue for the most significant collection of Martinez’s work (Arte Caliente: Selections from the Joe A. Diaz Collection) in 2004. Martinez is also featured in all of Cordova’s writings on the Con Safo art group, including Con Safo: the Chicano Art Group and the Politics of South Texas (2009), which was the first book written on a Chicano art group.

3 comments

Fascinating intersections of folklore, history, and gender.

Yes, Daniel, there is a lot going on in this painting. I enjoy writing about artists that engage with culture and history.

I’ve loved Martinez’s art for decades drawings and paintings–I first saw his work in the monthly Chicano review Caracol. I wrote this praise poem for Cesar a few years ago.

On the King’s Road in San Antonio, Tejas

(for Cesar A. Martinez)

Humble householder, modern-Tejano Toltec

welcomes us to his armadillo-corrugated casa

he opens his guarded black-clippings binder.

It reveals a parade of rostros de los Chicanos muertos

and others posed in their favorite or final public photos.

We ponder once alive many ceased orbits,

and notice how heat has oxidized white print–to brown.

His draws and paints as deliberate as science allows

he forms prisms from the heart crystal, out of each

human face, resurrection springs in new colors.

Inside the artist’s mindstudio a magician’s

mortuary, without mourners’ tears,

or egocentric memories.

Decades gone grins, sunglasses,

squints and sampaku stares live again,

afloat on the tapestry of luxuriant

magentas, greens and umbers.

Cesar’s magic a peyote kaleidoscope

snapped open, towers of firecrackers

sizzle in a torrent of canvas strokes.

While listening to silver chords of España’s

flamenco which accompany him as he

strikes and strums one magnetic brush,

flashing side to side, open closed,

like el toreador’s dance to free

the bull of blindness with shafts of light.