Since April 1, 2023, a selection of 13 images from Richard Avedon’s In the American West have been on view at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth. Even as a photographer who adores this series, I wasn’t compelled to see the show right away; it’s been on my radar, but I didn’t feel a rush. This is partially because I’ve seen some of the works in person before and I’ve seen many others online and in books. Essentially, I know what they are and why they matter, but in a world where new art is going up and coming down every few weeks, it is hard to justify pausing to revisit photographs I’m already quite familiar with. So, when I did finally encounter the exhibition last month, during a visit to see other new pieces at the museum, I was surprised to find a new sense of dynamism in the images. The work stopped me in my tracks and made me take notice.

Rather than being presented together, as a traditional exhibition, the photographs making up Avedon’s West are scattered throughout the museum’s permanent collection galleries. This style, of presenting contemporary works alongside historic pieces, is not new. The Carter (like other museums) has been breathing new life into its permanent collection by juxtaposing older pieces with newer ones for many years. This is, however, the first time I can recall the Carter doing this in a pointed, purposeful way, with works by a singular artist. It is understandable that Avedon’s work would translate well into this type of presentation — it is so cohesive that even when split amongst multiple spaces, it is clear that the images are part of a series and belong together.

The Carter’s exhibition is part of a larger celebration, led by The Richard Avedon Foundation, to mark the 100th anniversary of the artist’s birth. While other venues, like Gagosian in New York City, put on exhibitions of Avedon’s portraits of artists, designers, musicians, and fashion icons, it is fitting that the Carter display works from the artist’s In the American West series, which was commissioned by the museum’s first director, Mitchell A. Wilder.

In 1979, at the time of the commission, Avedon was known for his iconic portraits of celebrities of all stripes, including The Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Marilyn Monroe, Bob Dylan, Samuel Beckett, Alberto Giacometti, and Marian Anderson. Along with these posed photos, he had also shot more candid moments, like the images in his series New York Life and Santa Monica Beach, which document everyday life. At that time, the Carter was still a museum of Western Art (think Frederic Remington and Charles Russell, whose work formed the basis of Mr. Carter’s original collection), and not as its current name more broadly states, American Art. And so, it would make sense that Wilder would be interested in commissioning a contemporary take on the American West to buttress the museum’s collection.

“In the American West,” the original presentation of Avedon’s series at the museum, 1985. Photo courtesy of Amon Carter Museum of American Art

Avedon worked on the project from 1979 to 1984. During that time he traveled to nearly 200 towns in 17 states, including Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, and Wyoming. According to the Carter’s website, the artist “conducted 752 sittings, exposing 17,000 sheets of film”; the final series contains 124 photographs.

In 1985 the Carter presented In the American West: Photographs by Richard Avedon, which received national acclaim. Since then, from time to time, the museum has shown some works from the series as smaller exhibitions. In 2005, John Rohrbach, then Senior Curator of Photographs at the museum, curated a selection of images from the series to mark the 20th anniversary since the original exhibition. In 2017, the museum also displayed images from the series that specifically focused on Texas in the exhibition Avedon in Texas: Selections from “In the American West.”

“Avedon in Texas: Selections from In the American West,” February 25, 2017–July 2, 2017. Photo courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art

The current exhibition, Avedon’s West, is curated by Dr. Kristen Gaylord, the museum’s former Associate Curator of Photographs. What strikes me about her arrangement of the works is that even though Avedon’s photographs are stunning and a room full of them carries weight, seeing the iconic pieces in a new context — among landscape paintings, western scenes, and in dialogue with modern works — increases their power exponentially.

One of the most striking examples of this is the pairing of Avedon’s Blue Cloud Wright, slaughterhouse worker, Omaha, Nebraska, 8/10/79 and Steer, Slaughterhouse, Amarillo, Texas 11/19/81, which together sit between bronze sculptures of a bear cub and a buffalo and are set in a room of idyllic landscape paintings, which the museum refers to as the America As Landscape gallery. Seeing Avedon’s large-scale, black and white, high-contrast images in a space filled with serene paintings of wide-open spaces is at first jarring. But rather than being repelled by the harsh interjection of the works, I immediately understood the implication of these works in this space — these 19th century paintings of America seek to showcase the natural beauty of the U.S., but do so through rose-colored glasses; in effect, they leave out a huge part of the story of our country and its founding.

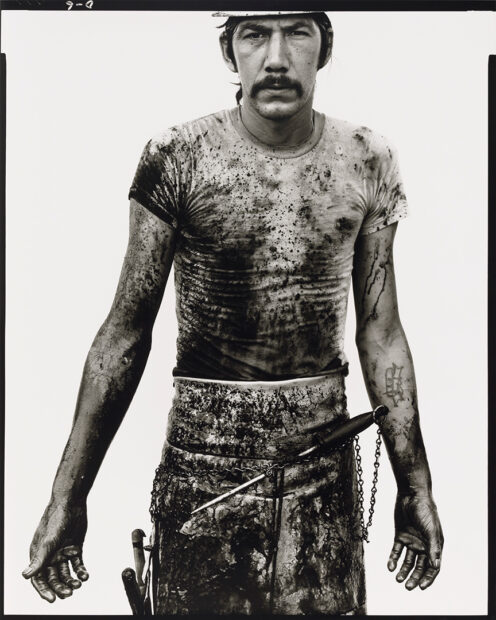

Richard Avedon, “Blue Cloud Wright, Slaughterhouse Worker,” 1979. Image courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

What’s missing from Albert Bierstadt’s Sunrise, Yosemite Valley, or even Thomas Cole’s The Hunter’s Return is the violence. Inserting Avedon’s 1979 photograph of a slaughterhouse worker with blood strewn across his shirt, apron, and arms, which even in black and white is unsettling, is an indictment of our society, our government, our ancestors, and the way they violently acquired the land we now call the United States. It completely changes the tenor of the rest of the room.

The image of Blue Cloud Wright on its own, or merely in the context of In the American West, might not bring such a strong reaction. At face value it is simply a portrait of a working man who is part of an industry that often goes unseen or overlooked. Viewed side-by-side with Avedon’s depiction of a butchered steer’s head, the portrait is given additional context showing the size of the animal the slaughterhouse worker encounters, and therefore the extent of his work. But it is through this new context, among landscape paintings, that a larger narrative is exposed. The power behind Gaylord’s curation is that it reveals something new about Avedon’s work, about the otherwise peaceful landscapes, and about the history of our country.

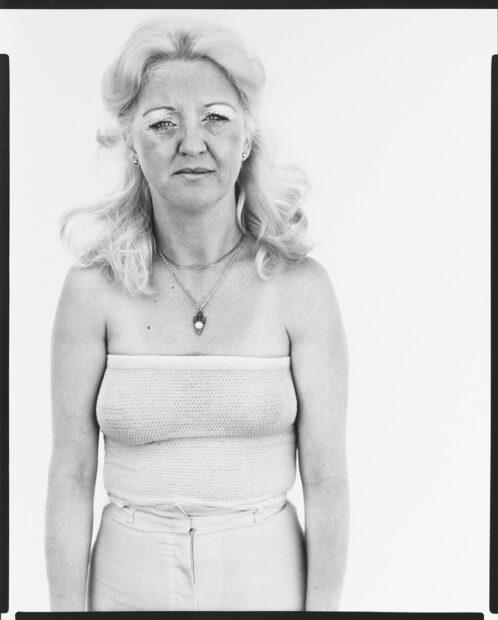

In the next gallery over, Gaylord has paired Avedon’s Carol Crittendon, bartender, Butte, Montana, 7/1/81 with Charles M. Russell’s In Without Knocking. The painting, completed in 1909, depicts a turbulent scene of cowboys on horseback wielding guns outside of a bar/hotel. Playing cards litter the ground and add to the atmosphere of whirling dust and smoke. One man on a horse enters the doorway of the hotel while the other riders approach the porch. Like much of Russell’s work, the rowdy painting depicts the American West as a place inhabited by dangerous men. This is definitely part of the story, to be fair, but it isn’t the whole story. Juxtaposing this masculine painting (and really the gallery as a whole) with Avedon’s portrait of Carol Crittendon is a reminder that women, too, were and are a part of the American West.

Richard Avedon, “Carol Crittendon, bartender,” 1981. Image courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

Even more so, it is notable and purposeful that Gaylord selected not just any woman, but one whose job as a bartender puts her squarely in conversation with Russell’s scene. There is much about the narrative in Russell’s painting that is unknown. Who are the men on horseback? Why are they bursting into the bar? Who is inside the bar and what will happen next? The pairing of the works provides a new perspective to some of the potential answers to those questions. Perhaps Carol Crittendon, or some early 20th century version of her, is tending bar and will greet the unruly visitors. With a no-nonsense look on her face, she seems to be up for the challenge.

I am a bit ashamed of myself for not actively seeking out Avedon’s West sooner. It is an important presentation that, perhaps for the first time since Avedon’s work was shown at the museum, adds depth and new considerations to his photographs. Beyond that, the juxtapositions also bring contemporary issues and thoughts to light and ask visitors to reconsider traditional takes on 19th and 20th century artworks.

Avedon’s West is on view at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth through October 1, 2023.