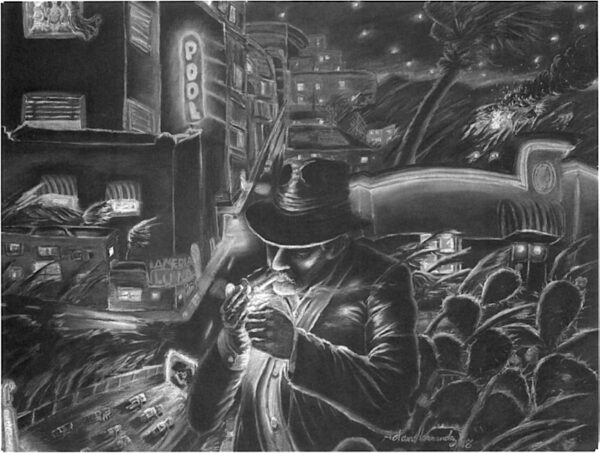

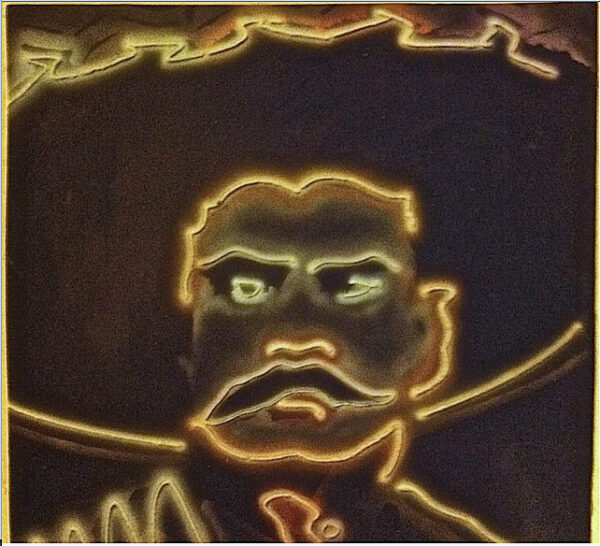

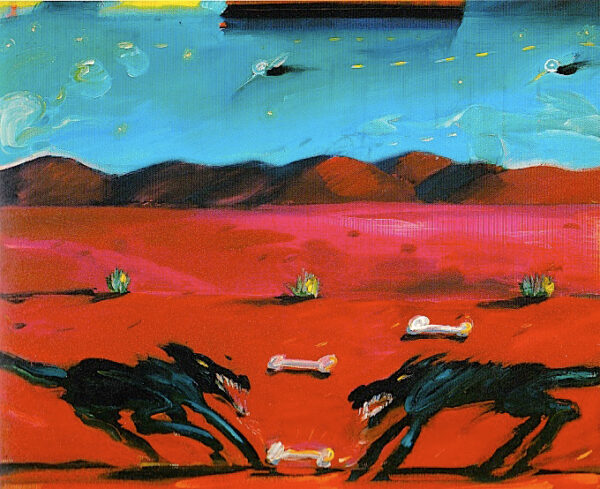

Adan Hernandez, La Media Luna (detail of lower section), 1988, oil on canvas, 60 x 60 inches, collection of Sean Ferrer, Los Angeles. Photo source: flickr.

This is the first of four articles that take a personal, unvarnished look at the career of the San Antonio-based painter Adan Hernandez (October 15, 1951-May 15, 2021). It focuses on the genesis of the artist’s signature “Chicano noir” style, and the family trauma and artistic influences that impacted its creation.

“Adan Hernandez Paints the Black of Night, Part 2: From Photorealism to Chicano Noir and Back Again” will look at his first exhibition in 1985 and trace the stylistic development of his individual works.

“Adan Hernandez Paints the Black of Night, Part 3: Blood In, Blood Out and Gang Imagery” will examine the art Hernandez created for Taylor Hackford’s film (released in 1993), as well as the artist’s paintings through 1999, which grew darker and more violent.

“Adan Hernandez Paints the Black of Night, Part 4: Fade to Monochrome” will posit that another family trauma led to his more uniformly dark and monochromatic mode of painting. This last article treats the final two decades of Hernandez’s career and his legacy as an artist.

Adan Hernandez (October 15, 1951-May 15, 2021), La Media Luna, 1988, pastel on paper, 22 1/4 x 30 inches, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo source: Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Fall 1991 (the pastel is in color, though the reproduction is black and white).

I first encountered Hernandez’s work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the summer of 1991, when I was in a doctoral program at U.C. Berkeley. I saw his painting La Media Luna in an exhibition called Drawings: Additions to the Collection; I was astonished to see a work by a Chicano artist in the show, and as far as I can tell, he was the second Chicano artist to be represented in that august museum’s collection (see Chicanos in the Met in the appendix at the bottom of this article). I was deeply impressed by the power and originality of his vision. As someone with a deep interest in film noir and neon, in addition to Chicano art, I was hooked. “Noir” is French for dark, and film noir is a term created by French critics for a stylish group of mostly low-budget, black-and-white doom-laden crime dramas from the 1940s and 1950s that were made in the U.S. For an introduction to film noir, see this short video by One Hundred Years of Cinema.

Noir films have magical lighting effects. In order to film at night, their makers had to hose down streets and buildings to create reflected light. This made the surfaces glow. Wet streets amplify light in a way that works especially well with haloed street lamps and flashing neon signs. There is no atmosphere quite like the one created by neon lights, as the neon rods flicker, flash, and go dim in hypnotic repetition. The directors of these films also lit actors and sets in stark, dramatic, and innovative manners. Low-key lighting produced foreboding shadows and silhouettes, and crazy angles and bursts of light created an indelible mood of danger.

Writing about the version of Media Luna executed in oil paint, critic Dan R. Goddard said “lines of neon glow against the purple darkness.” He added: “there is a mood of mystery and romance in the heat of the night” (“Chicano artists shine in Blue Star III show,” San Antonio Express-News, July 24, 1988).

Hernandez, whose love for nocturnal illumination is obvious, lights up the contours of his forms with thin bands of bright color that function much like neon light rods. The wall in the right background of Media Luna is apparently lined with neon. Other forms — including even the palm trees and cactus paddles — glow as if they, too, are ringed with neon.

From 1934 to the late 1950s, Hollywood studios practiced repressive self-censorship. To skirt it, filmmakers conveyed sexuality through double-entendre, innuendo, and symbolism, particularly during the heyday of film noir, when tough-talking dicks and molls meant more than they said. For a prime example, see Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall use horse racing as an extended metaphor for sex in The Big Sleep (1946).

In this censorious atmosphere, cigarettes were the focus of dramatic, often highly sexualized interchanges between men and women, a trend that has continued in neo-noir films. Films noir elevated cigarette lighting to the level of a sacrament, whether in the hands of a hard-boiled detective or a louche femme fatal. 99 River Street (1953) features one of the most dramatically symbolic lighting scenes.

The gesture of lighting a cigarette is the central action in La Media Luna, around which space twists in every direction, plunging dramatically below the man’s right arm, where cars at the El Capitán Drive-In are reduced to the size of a cigarette lighter. A man and a woman embrace on the tiny screen, at what is no doubt a dramatic point in a Mexican melodrama, a genre of film the artist enjoyed since childhood.

This man is alone. His only potential mate is a topless woman seen through a window in the upper left corner of the pastel. Will they meet at the Media Luna, the club just to the left of his cigarette-lighting hands? In any case, in this naked city (to use the title of a film noir), the only love to be had is evidently for sale. And if noir films teach anything, it is that the price exacted for this love will be life itself.

Adan Hernandez, La Media Luna (detail of lower left section), 1988, oil on canvas, 60 x 60 inches, collection of Sean Ferrer, Los Angeles. Photo source: flickr.

The man seems to be stepping out of some impossible space — perhaps a cactus-friendly cloud in neon heaven — into our world. But in fact, he has ensnared us to enter into his world. As Hernandez noted the year he made this work, “I like those old film noir detective movies and I like painting at night. At night is when I get my best ideas” (Goddard, “Chicano artists shine in Blue Star III show,” Express-News, July 24 1988). Hernandez’s character likely has much in common with the hero described by the quintessential pulp fiction writer Raymond Chandler in The Simple Art of Murder:

Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. The detective in this kind of story must be such a man. He is the hero, he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor, by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it… He is a relatively poor man, or he would not be a detective at all… The story is the man’s adventure in search of a hidden truth, and it would be no adventure if it did not happen to a man fit for adventure.

Unlike some characters in classic noirs, Hernandez’s man does not wear an immaculately pressed, double-breasted suit. He is clearly not an elite. As Leonard Pierce has emphasized in “The Working Class Cinematic Legacy of Film Noir,” this body of film is “important and electrifying today” because it was “the most class-conscious genre of motion picture America has ever produced” (Jacobin, October 11, 2020). Pierce notes that the thieves, hoods, and assorted minor villains pale in comparison to the “truly contemptible figures,” because “the rich, whether from the straight world or the crooked ones, are monsters, soulless things, icons of cruelty who will double-cross and dirty deal to protect the wealth they already possess in abundance. Even in a rigged game, they refuse to play fair.”

Adan Hernandez with a man dressed as a pachuco, Guadalupe

Cultural Arts Center, 2009. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova. Hernandez liked this man’s classic 1940s-era Zoot Suit so much that he asked me to take pictures of the two of them together. Hernandez is wearing the Stacy Adams two-tone wingtips that would be the subject of his very last painting.

Hernandez’s smoker is a pachuco, a member of a subculture that likely originated in the 1920s and 1930s in the border cities of El Paso and Juárez. Their heyday was in the 1940s and 1950s, when they wore Zoot Suits and drove low riders. Hernandez told me pachucos are “to this day — the coolest thing to behold in fashion, manner, and speech.” Hernandez was a painter of the dispossessed. More specifically, he was a painter of the Chicano, against whom the system is doubly-rigged.

I made another association when I saw Hernandez’s pastel: I thought of the distortions and arbitrary lighting effects of El Greco, and of three paintings he made of figures illuminated by a burning ember, which were inspired by a description by the Roman writer Pliny of a lost painting. (I discussed them in a Glasstire review of an exhibition at the Kimbell Museum of Art.) One of these paintings (now in the Prado Museum) had been on loan to the Metropolitan in the 1980s, and I wouldn’t be surprised if someone at the museum also associated Hernandez’s pastel with El Greco. Mike Greenberg, in the Express-News (April 4, 1999), linked Hernandez and El Greco as artists who “take us out of the real… by peeling the surface.” El Greco’s manner of constructing forms is, of course, very different from Hernandez’s illuminated, linear contours. After all, El Greco never knew neon — but I’m certain he would have loved it.

In the fall, the Met’s Bulletin illustrated the pastel in black and white. The commentary by assistant curator Lisa M. Messinger (some of which had been included on the exhibition label) noted that Hernandez had made “haunting aerial scenes of San Antonio at night” since 1987. In her conclusion, she quoted the artist, who spoke of “lifelong feelings of alienation and uncertainty, which still dominate the Chicano community, where most live on the fringes of the American dream.” Noting how Hernandez’s orange stars and night sky resembled those of the expressionist painter Carlos Almaraz (1941-1989), I wondered what connection he might have to California-based Chicano artists.

Adan Hernandez, La Media Luna, 1988, oil on canvas, 60 x 60 inches, collection of Sean Ferrer, Los Angeles. Photo source: flickr.

The Met’s Bulletin notes that the pastel is a study for a larger painting, which had already been snapped up the previous fall by production designer Bruno Rubeo. He saw it at the Jansen-Pérez gallery on Houston Street in San Antonio, when he was primarily scouting shooting locales for the film Blood In, Blood Out (released in 1993). This encounter is how Hernandez was chosen to create the paintings featured in the film. Larry Ratliff, the San Antonio Light’s film critic, notes that Hernandez got an initial phone call on October 15, his 30th birthday, and remarked: “My life has been a whirlwind since then” (“Filmmakers find ‘look’,” Oct. 24, 1990).

In October of 1990, according to Oscar Garza in Texas Monthly (“Blues in the Night,” September 1991), it was like a scene in a movie. He writes that Hernandez didn’t have the money to complete the painting he was then working on, so he called Jansen-Pérez, intending to remove his paintings from the gallery so he could photograph them in an attempt to get representation in Los Angeles.

This makes for a dramatic story, with Hernandez almost missing his date with destiny and his consequent rescue from penury. But removing his works would have violated his contract. Moreover, Jansen-Pérez chose artists on the basis of slides, and it did excellent photography (at Berkeley in the 1990s, I used ads the gallery placed in Latin American Art to make slides of Hernandez’s work). Since Hernandez had not sold anything at Jansen-Pérez or at his previous gallery (the DagenBela Galeria in Market Square), and since he would be breaking his contract, it’s hard to imagine a Los Angeles gallery would want to take on this unknown Texas-based Chicano artist. It’s even less likely that the same gallery would advance him money to complete his unfinished painting. Hernandez never told me the melodramatic and sometimes fantastical tales he told others, some of which I will discuss in the appendix to Part 2.

Garza tells us that gallery co-owner, Sofia González Pérez, answered the phone and informed Hernandez that Bruno Rubeo was in the gallery. Rubeo thought Hernandez’s paintings were perfectly suited for the film. Garza quotes Rubeo: “Adán is the essence, the spirit of Chicano art.” This is how Hernandez always characterized his art to me, as the embodiment of Chicano art. Rubeo added: “He is genuine and real, and his paintings are so cinematic. Some of them even have images that look like a storyboard.”

According to Hernandez, Media Luna was also the favorite painting of the film’s director, Taylor Hackford. He flew into San Antonio after Rubeo had spotted Hernandez’s work. Ratliff notes that Hackford purchased Un sueño en la noche (A dream in the night) and placed Pachuco con Jumper Cables (illustrated below and discussed in Part 2) on reserve.

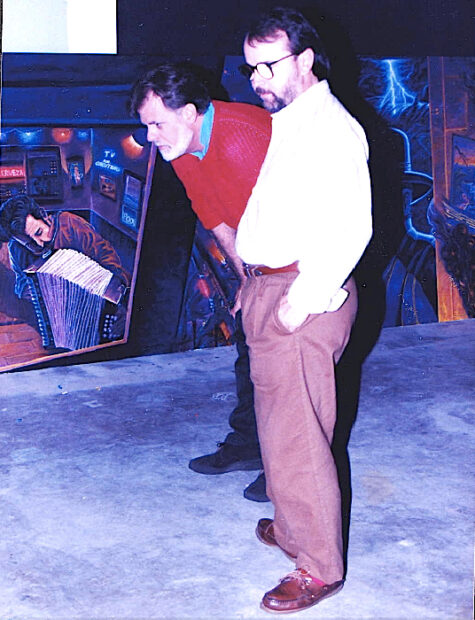

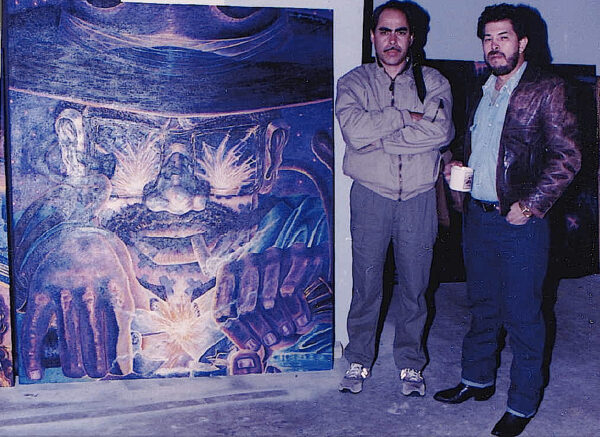

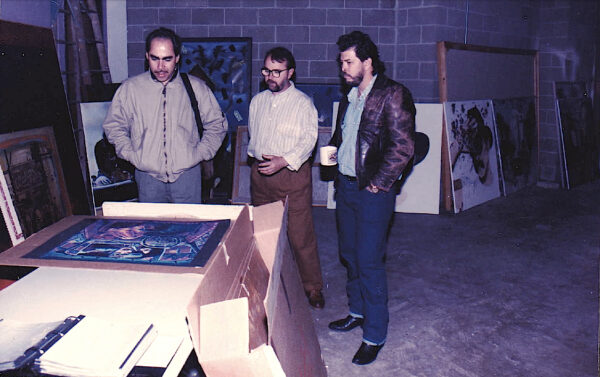

From left to right: Jimmy Santiago Baca, writer of the screenplay for Blood In, Blood Out; Bruno Rubeo; Sofia Pérez; Adan Hernandez; and Taylor Hackford in an unfinished space that would become Gallery B at the Jansen-Pérez gallery, October, 1990. The painting partially visible behind Rubeo must be Emiliano Electrico (1985), though it appears bluer than in the illustration below. The large painting between Pérez and Hernandez is Los Brillosos (1988), which is illustrated and discussed in Part 2. Photo source: Sofia Pérez.

Hackford told David J. Fox of the Los Angeles Times that Rubeo “happened to go into the Jansen-Perez Gallery and was immediately blown away when he saw the work of Adan Hernandez” (June 2, 1991).

Taylor Hackford and Bruno Rubeo in an unfinished space that would become Gallery B at the Jansen-Pérez gallery, October, 1990. The painting in the left background is Tierra del Sol (1988); the one in the right background is El Ladron (1990). Both paintings are illustrated and discussed in Part 2. Photo source: Sofia Pérez.

Having failed to find an unknown Los Angeles-based Chicano artist that evoked the barrio, Hackford deemed it “astounding” that Hernandez’s paintings had “all the elements of Southern California’s geography — fires in the hills and palm trees.” Fox also quotes Pérez, who said Hernandez’s work “is very expressionistic and intensively pushes the imagery of the barrio. It could be Los Angeles, but it happens to be San Antonio.” As a locale for filming, however, San Antonio was rejected because its barrio was too flat to pass for Los Angeles. This story — the only one I found that discussed Hernandez in a national newspaper — was distributed nationally by the L.A. Times-Washington Post News Service, and it appeared in many local papers across the country.

Jimmy Santiago Baca and Adan Hernandez in an unfinished space that would become Gallery B at the Jansen-Pérez gallery, October, 1990. They are standing next to Pachuco con Jumper Cables (1990), which is illustrated and discussed in Part 2. In the October 24 article cited above, Ratliff noted that Hackford reserved it for a pivotal role: it was to be the painting the film’s fictional artist paints after he comes out of a “funk” following a tragic accident. Hackford ultimately bought the painting, though it did not appear in the film. Photo source: Sofia Pérez.

When he wrote the Texas Monthly article, Garza was the arts editor of the Los Angeles Times. He had served the same role at the San Antonio Light, in which capacity he met Hernandez in San Antonio. Luckily for me, Garza began his career at a young age, or I might have needed a Ouiji board to track him down, instead of Google. I was intrigued by how Garza described Hernandez when he interviewed him in Los Angeles for Texas Monthly: he was “wrapped in a trench coat and sipping red wine as he sits by the pool in a friend’s back yard.” Unfortunately, there are no photographs from the interview, but Garza did disclose that the conversation took place at Bruno Rubeo’s house. Garza specified in the article that Hernandez received a five-figure contract “to paint about twenty canvases” for Blood In, Blood Out. I asked Garza to characterize Hernandez’s frame of mind at that time, and he replied: “He seemed like he was sincerely grateful for the opportunity.” Garza put me in touch with Pérez, who is living in San Antonio after many years in Los Angeles.

Jimmy Santiago Baca, Bruno Rubeo, and Adan Hernandez in an unfinished space that would become Gallery B at the Jansen-Pérez gallery, October, 1990. They are looking at a pastel (on the table) that features a couple at a drive-in whose car appears to be floating above the screen. (This theme would reappear in a large painting called Pelicula in 2005). Other pastels mounted on cardboard are in the box in the foreground. The painting on the floor on the extreme left is Esperando El Bos (Waiting for the Bus, 1984). A pachuco with sunglasses — a small version of the first painting Hernandez sold in 1985 — is directly behind the artist. To its right, one can see the paint-splattered Pachuco No. 2 (1984) and Con la Mosca (1983). They are discussed and illustrated in Part 2 in connection with Hernandez’s first exhibition. The latter two also appear in the film Blood In, Blood Out. I have identified eleven paintings in the pictures provided by Pérez (though Un sueño en la noche (A dream in the night) and Juan and his Ruca Had a Close Encounter are not in the Pérez pictures that I have published in this article). Additionally, there are several more (most only partially visible, and some clearly not by Hernandez) that I cannot identify. Photo source: Sofia Pérez.

Sofia González Pérez has a thick Spanish accent that is difficult to place geographically. I asked where she was from; she laughed and explained that she was born in New York to a Lithuanian mother and an Oxford-educated Spanish father, who was a diplomat for the U.K. She had grown up “all over Europe and Latin America.” Tragically, her father died from the effects of torture after being kidnapped and held for ransom in Guatemala in 1973.

As a child, she used to climb volcanoes with her father. “I traded volcanoes for artists,” says Pérez, with the sly implication that they are kindred entities. A winner of international prizes as a fine artist in Latin America, Pérez had a degree in architecture and was studying art at the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) and working at the Arte Moderno gallery in San Antonio when Angelika Jansen approached her with an offer to finance a gallery they would run in partnership. When they began their new gallery, Jansen, who was teaching German and German literature at New York University, primarily handled European and German-American art. Pérez, who concentrated on Latin American and Chicano art, was receptive to the latter because of her exposure to Latin American art.

When she met Hernandez she was working at the Arte Moderno Gallery. Pérez remembers being particularly impressed by Hernandez’s use of color, and his “gift for narrative, for story-telling.” Pérez recalls that Hernandez’s work initially seemed too brash, too loud, too colorful, and too déclassé for Jansen, who said: “this is not us” (meaning it was not right for the gallery). Pérez prevailed, and the first exhibition at Jansen-Pérez was devoted to Hernandez and Cesar Martinez.

I wanted to know what Hernandez was like before he was discovered by Hollywood and the Metropolitan, but Pérez was reluctant to characterize him. She made candid remarks only after many hours of interviews, when I kept circling back to the same questions. “When Adan first approached me, he was arrogant. He knew that he was good,” she recalls. Ultimately, Pérez learned almost nothing about Hernandez and his background. She didn’t know, for instance, that he had performed migrant labor in the fields with his family. Unlike the gallery’s other Chicano artists, Pérez and Hernandez “didn’t talk much, because he was not friendly. He was a very angry person. He was resentful. He felt he was owed.” She added: “Adan was not communicative.” Moreover, he “made you understand that you were not worth his attention.”

I told Pérez that I found it odd that Hernandez did not try to ingratiate himself to his dealers, since they had so much influence over his career. She replied with this insight: “I was also the ‘mother’ of all of his competitors.” From Hernandez’s highly competitive perspective — which I also address in another section of this article — Jansen-Pérez was doing more for other artists (cumulatively) than it was doing for him as an individual. Pérez says that even on a very minor level, she worried: “Oh my God, am I going to offend him today if I say ‘good morning’?” By contrast, she regarded Hernandez’s wife Debi as “an angel,” a person who was friendly, outgoing, supportive, and who smoothed over rough edges and grounded the artist in reality.

I tried to reach Angelika Jansen through multiple channels for this article, but did not get a response.

Gallerist Lisa Ortiz represented Hernandez before and after Jansen-Pérez. She described Hernandez as “moody” and “hot-headed.” She said she did not talk to Hernandez for quite some time after Blood In, Blood Out, “because his head got so big he wouldn’t talk to anybody.”

Hernandez moved next-door to Cesar Martinez by 1987, and they were in several exhibitions together. But Martinez could not say much about him before Blood In, Blood Out, other than to note that Hernandez was a busy family man, a good neighbor, and that they both minded their own business.

Eduardo Díaz, currently the Director of the Smithsonian Latino Center in Washington D.C., interacted with many artists when he was the Director of Cultural Affairs in San Antonio from 1989 to 1999. I asked him for a statement, and he gave me the following:

“Adán was a very gifted painter. His noir sensibilities drew out aspects of San Antonio other artists didn’t pick up on. My sense is that he didn’t understand what it took from a business side to be a completely successful artist. In the art world, building and nurturing relationships are critical to success. I got the impression he felt that he was owed exhibitions, that he should be more actively collected, that he should be as well known as some of his contemporaries (e.g., Mel Casas, Jesse Treviño, César Martínez, Kathy Vargas, etc.). None of these shortcomings, however, take away from the fact that Adán Hernández was one of the most important Chicano artists in San Antonio.”

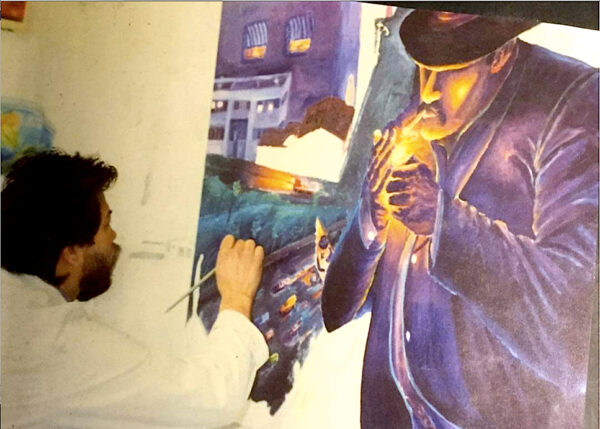

Hollywood production designer Bruno Rubeo in his house with La Media Luna (1988) and a painting I tentatively identify as Un sueño en la noche (A dream in the night, 1990). Photo source: Adan Hernandez.

According to Goddard (“World taking notice of Hispanic artists,” Express-News, June 30, 1991), before Rubeo spotted the piece in the window of the San Antonio gallery, Media Luna had failed to sell at a price under $4,000. Goddard, who doesn’t reveal that Rubeo purchased the painting, says it sold to a Californian “for a five figure price,” and that it was on sale for over $100,000 in L.A., where it eventually sold for $60,000. This never-surpassed price was one that Hernandez proudly noted on many occasions. He told me that Rubeo had purchased the painting, and that Rubeo held parties attended by his Hollywood associates where Hernandez’s paintings were “auctioned.” In a 2011 comment on flickr, Hernandez explained: “The only reason this painting sold for that much was because 2 other people in LA also wanted it.” He added: “This was my first Chicano Noir painting.”

Photographic evidence shows that Hernandez began Media Luna in a rather conventional manner, with more detail than would ultimately be necessary. He subsequently boosted the contrast and added highlight effects that mimic neon light rods.

Adan Hernandez, Emiliano Electrico, 1985, acrylic on canvas, private collection. Photo source: Facebook. This image is cropped.

In Emiliano Electrico, a depiction of the Mexican revolutionary general Emiliano Zapata, Hernandez had already demonstrated that a painting made up of neon outlines sufficed to render a likeness of his subject. (Though true neon would “blink,” since the rods would not all be lit simultaneously.) By utilizing neon-like outlines in Media Luna, Hernandez was able to create brilliant effects in his night paintings. In Part 2, I’ll discuss Los Brillosos (1988), a half light, half dark painting, as an intermediary step in this process.

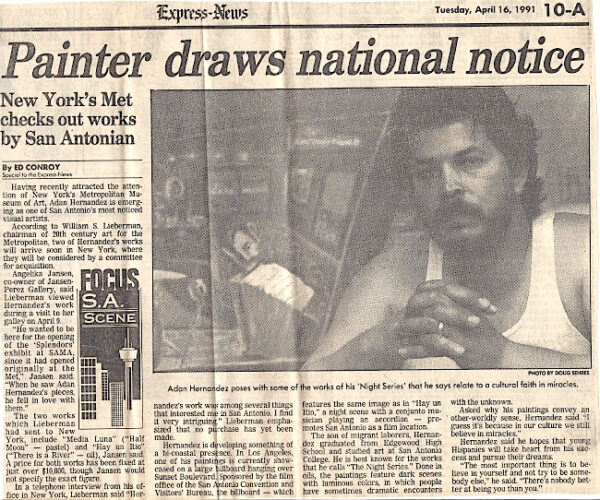

San Antonio Express-News article, “Painter draws national notice,” by Ed Conroy, April 16, 1991. Clipping courtesy of Dan R. Goddard.

The Met’s purchase of both the Media Luna pastel and another work by Hernandez, Hay un Rio, is treated in Ed Conroy’s special to the Express-News, “Painter draws national notice” (April 16, 1991). William S. Lieberman, the chair of modern art at the Metropolitan, had come for the San Antonio opening of the exhibition Mexico: Splendors of Thirty Centuries, which had originated at the Metropolitan.

The Mexican government promoted exhibitions at select galleries in each city that hosted the Splendors exhibition. Jansen-Pérez hosted two exhibitions of Mexican art to complement Splendors, which were visited by dignitaries that included Mrs. Cecilia Occelli de Gortari, wife of Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, who was accompanied by San Antonio Mayor Lila Cokrell (Goddard, “Mexican Art Displayed,” Express-News, April 25, 1991).

Lieberman visited the Jansen-Pérez gallery because it was on a circuit of art galleries that had been approved and promoted by the Mexican government. When Jansen-Pérez opened a branch in Los Angeles in October of 1991 to coincide with the opening of Splendors at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Jansen noted that representatives of the Mexican president had “urged us to open a gallery in Los Angeles” (Goddard, “Jansen-Pérez Gallery expands,” Express-News, September 13, 1991). Also see the appendix at the end of this article, which discusses Jansen-Pérez’s expansion to L.A. and the 1990 Tejanos exhibition in Mexico City.

On his April 9th visit to Jansen-Pérez’s gallery in San Antonio, Lieberman selected two works for the Met by Hernandez that were not part of an exhibition. It was a chance encounter, since Lieberman journeyed to San Antonio to see the exhibition at the San Antonio Museum of Art, and he visited Jansen-Pérez to see related exhibitions of Mexican art. The two works by Hernandez sold at just over $10,000, with the accessions subject to the approval of the museum’s acquisition committee. They were purchased with a fund earmarked for living American artists. Lieberman described Hernandez’s work as “very intriguing.” Pérez referred to the sale as “an extremely important stamp of approval” for Hernandez (“Museum buys 2 local works,” San Antonio Light, April 10, 1991).

Conroy also noted that Hernandez considers these works to be part of The Night Series. The title of one piece, Hay un Rio, probably refers to Hay un Río de Vida, a religious song about a river of life that heals the sick and confers happiness.

When Conroy asked Hernandez why his works conveyed an otherworldly sense, the artist replied: “I guess it’s because in our culture we still believe in miracles.” Conroy also mentioned a city-sponsored billboard in Hollywood, California that reproduced part of Hay un Rio, which I discuss below.

The Media Luna motif thus figured in both of Hernandez’s greatest triumphs — in Hollywood, and in New York. It had qualities that were familiar and appealing to anyone with even a passing knowledge of film history. So it is no surprise that — among Hernandez’s creations — one version of the piece became the darling of his Hollywood collectors and the other was one of the two works purchased by the Metropolitan.

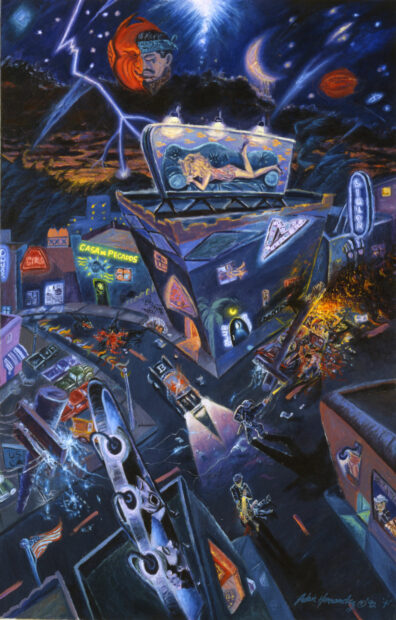

Adan Hernandez, Hay un Rio (There is a River), 1991, oil on canvas, 36 x 49 1/2 inches, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo source: Metropolitan Museum of Art website (the painting is in color, though the reproduction is black and white).

After seeing the pastel version of Media Luna, I searched the Met’s annual report (this was before the age of websites) and found that the museum had also purchased a major painting by Hernandez in 1991, titled Hay un Rio (There is a River), which was exhibited at the museum after its acquisition in 1991, and again in the mid-1990s. In this painting, Hernandez imagines San Antonio as a megalopolis. Anyone who saw this painting and subsequently visited San Antonio expecting to see a retro-futuristic city along the lines of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) or Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) was likely very disappointed, since the scale of Hernandez’s painted city arguably reflects these films more than the city itself. This gigantic city of dreams was crafted on canvas from multiple sources, and the real city of San Antonio (from which he drew elements that were distinct in time and place) was only one of them.

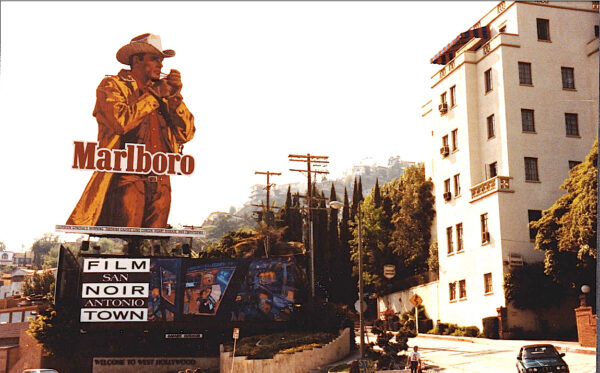

Billboard on Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood, with a detail of Hay un Rio (There is a River) by Adan Hernandez, 1991. Photo source: Sofia Pérez.

The Met’s painting received bicoastal exposure through a billboard with a detail from Hay un Rio on Sunset Boulevard in L.A. (coincidentally, Sunset Boulevard is the title of a classic noir). It was designed by the San Antonio film commission for the Convention and Visitor’s Bureau. An unsigned article in the San Antonio Light on April 6, 1991 (three days before Lieberman’s visit to Jansen-Pérez) titled “Artist’s creation planted for Hollywood eyes” says the billboard woos Hollywood with “the promise of a shadowy setting for intrigue.” Its juxtaposition of the text “San Antonio Film Noir Town” with Hay un Rio explicitly links the term film noir with Hernandez.

By the time I met him, Hernandez was not certain who had first used the term “Chicano noir” to characterize his work. The earliest references I have found are by Goddard: he used the term in connection with Hernandez in the Express-News on: September 30, 1997; July 26, 1998; December 9, 2001; April 7, 2002; and August 9, 2006. In the 2002 article, Goddard seems to attribute the term to the artist: “Hernandez’s paintings are disturbing visions of what he likes to call ‘Chicano noir.’” Goddard also used the term to describe Alex Rubio’s work on November 4, 2007.

Billboard on Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood, with a detail of Hay un Rio (There is a River) by Adan Hernandez 1991. The billboard featured another famous lighter of cigarettes in the background: the Marlborough man. Photo source: Sofia Pérez.

In the April 6 article in the Light, Hernandez observed that he wanted to avoid clichés and “show the side of San Antonio that is always hidden — La Raza.” In previous years, the commission had utilized graphics, rather than a painting, on its billboard. Film commission director Kathy Rhoades mentioned competition from Illinois, San Diego, and Alaska — the latter with a three-dimensional billboard. She reported that San Antono’s 1991 income from Hollywood had already totaled $3.4 million, in comparison to $2.3 million in1990. The article also notes that Hackford and Rubeo had purchased two of Hernandez’s paintings from Jansen-Pérez in the fall of 1990.

Adan Hernandez, They Don’t Want Me in My House, II, 1992, oil on canvas, 66 1/8 x 42 3/8 inches, private collection. Photograph courtesy of the National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago. Photo credit: Kathleen Culbert-Aguilar.

In 1995, I thought Hernandez and the California artist John Valadez were the two stars of the major traveling exhibition Art of the Other Mexico, which I saw at the Center for the Arts in San Francisco. Organized by the museum that is now called the National Museum of Mexican Art, it opened in Chicago in 1993 and traveled to six venues, including the Museo del Barrio in New York and the Museo Moderno in Mexico City. I saw that Hernandez’s work had grown darker and more complex after the pastel of La Media Luna that I had seen at the Met, as evidenced in particular by the painting They Don’t Want Me in My House II (1992). It struck me as a very film noir mode of painting, and, moreover, one that reminded me of noir’s roots in German Expressionist film.

The horror and noir genres share a common vocabulary rooted in early German Expressionist films, particularly Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922). Dr. Caligari has exerted an enormous, century-long influence on film; it presents a strikingly subjective vision of the world within an extremely complex narrative. Both directly and indirectly (through other German Expressionist films, as well as noir and horror films), it affected the structures and distorted spaces in Hernandez’s paintings. For a sampling of the film’s remarkable sets, see the short videos by Cinemassacre and Why It’s Great. Nosferatu provided Hernandez with unforgettable shadows, and a sense of supernatural menace. After he started working on Blood In, Blood Out in 1990, Hernandez’s art became explicitly violent, to a degree that only has parallels in modern horror and crime films.

Film noir is intimately connected to German Expressionist film because several German Expressionist directors emigrated to the U.S., where they worked in — and helped to create — the noir genre. As a scholarly reference, I recommend the book Film Noir and the Spaces of Modernity (2004) by Ed Dimundberg, my friend and fellow former undergraduate in the semiotics program (the film major) at Brown University, with whom I had many conversations about the connections between German Expressionism and film noir.

Hernandez’s twisted, elongated forms sometimes appear to be rendered in reverse perspective, seemingly growing larger as they emerge from the ground. Many of his paintings from the late 1980s and the 1990s exhibit traits such as sharp-angled edges, twisted and menacing corridors, ominous blind alleys, warped bridges, and other threatening and disorienting distortions featured in German Expressionist film. The most extreme examples can be found in the painted sets of Dr. Caligari.

The twisted hut where Dr. Caligari keeps the somnambulist named Cesare in a box. Photo source: screen grab from Dr. Caligari (1920).

Commencing in 1988, Hernandez utilized crooked structures with crooked windows (several of these paintings will be discussed in Part 2). In Dr. Caligari, the careening, distorted structures are so bizarre that only the most conventional ones — like this hut — could serve as viable models for Hernandez. One can see similarities between this hut and the central structures in They Don’t Want Me in My House II and Hay un Rio.

In They Don’t Want Me in My House II, Hernandez’s buildings, streets, signs — and even poles — are warped, distorted, bent out of shape. The sharp edges of these objects are menacing; at the same time, their impossibly enlarged forms render them vulnerable to collapse. The human inhabitants are seemingly endangered by the weaknesses of these structures as well as their strengths.

Adan Hernandez, They Don’t Want Me in My House II, (detail of upper section), 1992, oil on canvas, 66 1/8 x 42 3/8 inches, private collection. Photograph courtesy of the National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago. Photo credit: Kathleen Culbert-Aguilar.

A crying crescent moon — another manifestation of the Media Luna — drips dewy light on the distant horizon. In this symbol-laden painting, even the lightning in the upper left invokes a sharp-featured human silhouette. Beneath a floating, demonic head and a disembodied human heart, a pitchfork-like sprig of lightning stabs the earth, which bursts into flame.

Adan Hernandez, They Don’t Want Me in My House II, 1992 (detail of lower center). Photograph courtesy of the National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago. Photo credit: Kathleen Culbert-Aguilar.

The murderous policemen and the crashed car are testament to the dangers of the city — a point emphasized by the noir genre — while the billboards and neon herald its deadly allure. The toppled telephone pole serves as a gigantic cross for the prematurely deceased car crash and police shooting victims. There is horror aplenty in this painting, including frenzied canines that feast on road kill — which is potentially a human corpse. To emphasize class disparity, a homeless man sleeps on newspapers strewn on the sidewalk between the Casa de Pecados (House of Sin) and the large pool hall/night club in the center.

Supernatural retribution is close at hand. The hills are already aflame. Live wires crackle beneath the feet of the policeman as he shoots a crash victim. Thus we anticipate the cop’s imminent electrocution as instantaneous punishment for this murderous act; his long shadow portends his transit to the spirit world. The cop’s badge was, to use another noir title, a shield for murder. He was the man, accustomed to murdering Chicanos with complete impunity. But not this night. This time, when he pulled his trigger, he punched his own one-way ticket to hell. The intersection of the two streets forms a large black commemorative cross.

For a discussion of unwarranted deadly force utilized by police against people of color — including Chicanos in Los Angeles — see my Glasstire article Reyes I.

Nothing is as beautiful as electricity in the night — perhaps because this beauty is so energetically brilliant, so irresistibly powerful, so deadly.

They Don’t Want Me in My House II made me ponder Hernandez’s potential cinematic and artistic sources. I was certain he was referencing both film noir and German Expressionist film — including Dr. Caligari — and I thought it was brilliant to juxtapose these influences in the context of police violence, supernatural retribution, and cryptic religious imagery.

I viewed the Art of the Other Mexico exhibition as an admirer of Carlos Almaraz. I hoped to curate a retrospective of his work some day. (Subsequently, as the curator of the Mexican Museum in San Francisco, I wrote a grant funded in 1977 by the Judith Rothschild Foundation for an Almaraz retrospective, but a newly hired museum director prevented me from pursuing this project.) I was certain I recognized Almaraz’s influence in Hernandez’s dark blue night skies and orange stars, as well as his ravenous canines and burning cars. I also thought a couple of paintings in the Art of the Other Mexico exhibition also reflected Almaraz’s use of color in a very specific manner. The Death of Chuey (1991), which is discussed at the end of this article, is one of those paintings.

Hernandez’s neighbor, Cesar Martinez, recently informed me that he had given Hernandez a copy of the exhibition catalogue Hispanic Art in the United States (1987) in 1987. When I saw the Hispanic Art exhibition in California, I had been deeply impressed by many of the works that clearly influenced Hernandez, as I argue below.

Carlos Almaraz (1941-1989), Crash in Phthalo Green, 1984, 42 x 72 inches, oil on canvas, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo source: Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

One was Almaraz’s Crash in Phthalo Green (1984), now in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. It features what appear to be at least five fiery vehicles (one assumes there are at least two that make up the flaming, smoking form on the left). One car is falling from the elevated freeway, and others might follow. This painting provided a model of energy, dynamism, bright color, and loose technique. It also demonstrated that one doesn’t have to render a burning car in much detail — smoke, fire, and a flying tire conveyed a catastrophic crash in a more effective manner. Though cars rarely catch fire in real life, Hernandez followed Almaraz in making burning cars a favored motif. In addition to many flaming cars, Hernandez also depicted a flying car in his painting called The Squad-Car Opens Fire — the Chevy Crashes Thru the Guardrail (1993).

Almaraz’s car crashes express the noirish concept that a deadly disaster can strike at any moment, even on a leisurely Sunday drive. A pair of vintage cars on the lower level of the highway are unaffected, though they might still be bombarded by debris or a flaming chassis. These two cars in Almaraz’s piece are quite similar to the vintage cars in the used car lot in the left center of They Don’t Want Me in My House II.

Carlos Almaraz (1941-1989), Greed, 1982, 35 x 43 inches, oil on linen, private collection. Photo source: Hispanic Art in the United States catalogue.

The Hispanic Art catalogue also featured Greed (1989), an unusual Almaraz with ferocious canines. These vicious animals — so unlike Almaraz’s characteristically cuddly and benign hybrid creatures — inspired the general form of the canines in They Don’t Want Me in My House II. Slightly earlier, they had also inspired the enormous beasts — their gigantic snouts in particular — in La Muerte de Juanito, the large canvas Hernandez painted for Blood In, Blood Out (which I’ll discuss in depth in Part 3).

Adan Hernandez, The Death of Juanito (detail of four savage wolves attacking Juanito’s corpse), 1992, oil on canvas, 81 x 163 inches, estate of Adan Hernandez. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova. Hernandez had refused to show this painting to me in the first decade of the 2000s, because he knew I would want to take slides, show it to my classes, etc. He mistakenly thought that concealing the works he made for Blood In, Blood Out would create demand for a museum of his work. I sarcastically refuted this strategy: “Adan, that’s why millions of people line up to go to the Louvre every year: because they have no idea what the Mona Lisa looks like, and they want to find out.” He was unmoved by my argument. When Hernandez died, his family did not realize that he still possessed The Death of Juanito, which was rolled-up in his studio. The painting was mounted on a stretcher and displayed publicly for the first time on November 13, 2021 as a centerpiece of San Antonio’s Luminaria festival.

In La Muerte de Juanito, two beasts, with their fangs bared, approach from below. One wolf —just below the skeletal head — is already sinking his teeth into Juanito’s chest. A fourth, whose head is just above Juanito’s, appears to bear the Virgin of Guadalupe on its hindquarters. Note that she is borne by a skull-headed angel. The large skull above Juanito belongs to Santa Muerte, a death saint in popular religion that is disavowed by the official Catholic church.

A curving bridge (inspired by the one in Dr. Caligari) loops behind the Virgin of Guadalupe and Santa Muerte. It spans a river of blood and terminates in a spectacular car crash in the lower left corner of the painting. The loosely painted detail (reproduced above) reveals Hernandez’s masterful absorption of Almaraz’s style and subject matter. Hernandez’s loose and blurry gestures suggest that the car’s tires are flying off while it flips through the air.

Hernandez’s giant strip-joint breasts in They Don’t Want Me in My House II might have been inspired by what appear to be giant, disembodied breasts in Almaraz’s Love Will Make the City Crumble (1983), despite Hernandez’s antithetically dark and menacing vision of the city at night. The careening, sharp-angled buildings Hernandez painted in the late 1980s and early 1990s have clear sources in German Expressionist film, especially Dr. Caligari. But they might also have drawn inspiration from the buildings in Love Will Make the City Crumble (1983) and Two of a Kind (1986), two paintings in which Almaraz’s edifices seem to sway as much as Hernandez’s wind-blown palm trees.

Almaraz’s example was transformative on many levels. Rather than basing his work on a photographic image, Hernandez began to paint in a loose, expressionist manner with dynamic, unleashed color, as I argue here and in Part 2.

Hernandez Becomes an Artist

This is the story of how Hernandez became an artist, and how he evolved from photorealism to the style dubbed Chicano noir. He pinpointed his birth as an artist to a particular day, as I noted in a 2016 article on Jesse Treviño, who became San Antonio’s most famous artist.

Adan Hernandez experienced an epiphany at Treviño’s opening at the Instituto Cultural de México in 1981. Hernandez was staggered when he saw “images of the barrio” that he never imagined could be the stuff of art. “It opened up my whole consciousness and changed the direction of my life,” Hernandez said.

The very next day, the 30 year-old waiter decided to become an artist. He quit his job, went to the library to look at art books, and began taking pictures to serve as the basis for paintings.

Luckily, Debi Fischer, Hernandez’s girlfriend and future wife, understood how deeply he wanted to become an artist. She had a well-paying job at Southwestern Bell, and she encouraged him to quit his job and follow his dream, which he would not have done on his own. Hernandez repeatedly emphasized this point to me, and also to several writers, including Garza and Gary Sweeney in a 2015 interview. The catalogue Tejanos: Artistas Mexicano-Norteamericanos (1990) contains this statement: “In 1980, with the encouragement of his wife-to-be, Debi Fischer, he dropped everything and devoted all his time to painting.”

Hernandez — and everyone who utilizes him as a source — places the Treviño exhibition in 1980, but it took place in 1981. It was Treviño’s second solo exhibition, and his first in San Antonio. Anthony Head discusses it briefly in Spirit: The Life and Art of Jesse Teviño (2019).

Hernandez was hostile to institutions, a point emphasized in a two sentence statement in The Art of the Other Mexico catalog, which notes his “nature has always resisted the structures of institutionalized education.” Hernandez had dropped out of Edgewood High School in the ninth grade, and he also dropped out of the local community college, San Antonio College (SAC). His enrollment at SAC explains this laconic comment in The Art of the Other Mexico catalogue: “Adan Hernandez started his artistic career at age twenty.” Garza also states that Hernandez enrolled at the age of twenty, which would be 1972. By most accounts — including Hernandez’s personal account to me — he stayed only a semester. In the earliest reference I found, however, Steve Bennett says he “did a couple of years” at SAC in the early 1970s (“Los ‘Brillosos’ shines,” Viva, San Antonio Light, February 11, 1988). The Tejanos catalogue actually states that he graduated from SAC “with an arts degree.” I have uncovered no other sources that make this claim.

I am skeptical Hernandez was at SAC very long, since he noted to me — and several other people including Garza and Goddard — that he was unaware Mel Casas was teaching at SAC. Casas was the most famous professor of studio art in San Antonio, where he taught a generation of students. Commencing in December of 1971, Casas also served as the president and the chief spokesperson of the Con Safo art group. He was also a public intellectual of note. Given these multiple roles, Casas was the most influential of those artists who spent their careers in Texas during the second half of the twentieth century. So, if Hernandez had spent any appreciable time at SAC, how could he — as someone who complained that the program was too European — have been unaware that Casas was teaching at the college and leading a Chicano art group?

Hernandez was impatient when he was at SAC. He wanted to paint right away. Hernandez wanted immediate, practical instruction instead of the required introductory classes on drawing. He denounced San Antonio College to me as a “Greco-Roman institution.” Later, when he decided to become an artist, he skipped school altogether and “graduated himself” to the status of pintor (painter). Hernandez projected slides onto canvases in lieu of drawing, and he created photo-realist images broadly inspired by Treviño’s practice.

Even with all the spousal support in the world, success came slowly. Hernandez’s first exhibition (as noted in the Art of the Other Mexico catalogue, as well as in several newspaper articles) was a 1985 solo show at San Antonio’s Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center theatre. Hernandez was very pleased to make his first sale at this exhibition: Lionel Sosa — a pioneer in the field of Hispanic market advertising, who Hernandez always referred to as “the advertising guru” — bought the painting Pachuco (Part B) for $3,000. The sale was a crucial validation of Hernandez’s artistic vocation. But still, he said he only sold three pictures in his first decade as a professional artist.

This lack of commercial success wreaked an enormous psychological toll on Hernandez. He always spoke bitterly of the lack of respect that artists and collectors had shown for his work prior to his “discovery” in 1990-91. Even after his twin triumphs had garnered what he regarded as grudging respect, Hernandez felt that others were nefariously keeping him down. He never specified what this meant, but he did say he was “too Chicano” for other artists and for the art establishment, museums in particular. In my experience, Hernandez had a warm, gentle, and friendly personality, although he was also perpetually aggrieved.

His competitive nature was unfiltered. Jose Esquivel, one of the founders of the Con Safo art group, recalls that when he met Hernandez sometime after the release of Blood In, Blood Out, Hernandez said to him: “Esquivel, you are good. But not as good as me.” I related to Esquivel, that every time I ran into Hernandez when we were not in the company of others, he would say: “Ruben, are you still seeing so and so? Maaaannnn! She is bee-oooo-ti-fullll.” After a long pause, he would invariably add: “But not as beautiful as my girlfriend!”

Hernandez was unhappy with the criticism he received in the local newspapers. He often voiced this complaint to me: “Guys like Picasso — he had everybody to write about him — who do I have?” He was also unhappy when reviews or articles ignored his work. He would complain in written comments or emails that some of the artists were not very good, which the other artists generally took with mild bemusement. When I did not illustrate his work in a 2019 Glasstire article relating to my Alamo exhibition at the Guadalupe, he sent me this terse email: “The art shown is very clinical n boring!”

In his tally of sales, Hernandez does not include portraits and a one-off “cowboy” painting, which he said was a copy of a Frederic Remington (1861-1909) painting. He told me he made these in order to buy painting supplies, and did not regard them as examples of his “arte.” Prior to the fateful Treviño exhibition, Hernandez had painted on the walls of his apartments. Goddard reports that he spent ten years painting signs (Express-News, July 24, 1988; April 7, 2002). Hernandez told Garza and me that he had worked many odd jobs. Early on, Hernandez evidently wanted to emphasize that he had professional training and experience, so he told Bennett he had spent two years at SAC, and he told Goddard he had spent ten years painting signs. Subsequently, he decided it was more advantageous to position himself as a self-taught artist with little formal tuition.

Hernandez told Garza that after his various jobs, he made art at home “every night… just as he had since he was a kid.” By the time I met Hernandez in 2000, he dismissed all prior creative acts as “scribbles” and “doodles” that were likewise not part of his arte. A short bio on him on the site Brown Pride notes ten years of “doing slave work” before becoming a successful artist — as if the “slave work” was the only barrier to success.

I asked Armando Hernandez, one of Hernandez’s younger siblings, if he could shed light on Hernandez’s various jobs and art-making experience. Armando recalls that Hernandez’s spent a great deal of time making art of some kind. During his “hippie phase,” Hernandez made psychedelic posters, and he “wanted to have a hippie poster published some day.” He painted a woman on a wall of his apartment, whose long hair swirled around to the other walls.

Hernandez’s most cherished early creation was a Volkswagon Beetle, which he acquired in the late 1960s. Originally white, he painted it in psychedelic colors and peppered it with peace signs and flowers. This love bug had a tutu-wearing hippo ballerina, a portrayal of the Looney Tunes character Tweety Bird, and a giant American flag on the roof. The hood sported a peace flag in the Mexican national colors: red and green. In the rear, “flower power” was spelled out in lettering inspired by a Doors album. Hernandez couldn’t part with the car, even when he lived in Alamo Heights and drove a Corvette convertible. A hubcap he retained in his studio served as a talisman of his beloved beetle.

Armando recalls that Hernandez worked at several jobs. He was a militant sanitation worker, who went on strike and was fired for advocating worker’s rights. He was also a haircutter, who was inspired by the 1975 Hal Ashby film Shampoo, and the belief that “it was a good way to get chicks.” But he only learned how to do one style, and, said Armando, “that’s why all the kids in the barrio had the same haircut.” Armando said Hernandez also painted murals for bars. Hernandez was working at the Hyatt when he quit his waiting job to become an artist. Armando thinks Hernandez also worked as a bartender. He never heard that Hernandez painted signs, much less for ten years. But he says Hernandez was a commercial illustrator at the Atkins Group for several years, around the time of his 1985 exhibition at the Guadalupe.

Armando recalls that their sister Rosemary told Hernandez “not to lie about having a degree.” I asked Armando if Hernandez had ever been caught providing false information on an application. He replied: “If he did, he wouldn’t have told me.” When I met Hernandez, he hadn’t learned his lesson. His CV had false information that jumped off the page the first time I looked at it. He, for instance, claimed to have been in the famous Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation (CARA) exhibition that toured the United States in 1990-93. I told Hernandez that one false statement could make him lose credibility (and all opportunities) with museums and galleries in the big cities. I said that if he lied on his CV, they would not have confidence that he would honor his contract, deliver his work on time, and refrain from double-dealing behind their back.

Hernandez had very concrete ideas about what constituted arte. He had dashed off a small sketch of a skeleton playing an accordion on an unstretched canvas that, for many years, was tacked up in a corner of his studio. Since Day of the Dead is one of my main research interests, I wanted it. But Hernandez, who was dismissive of the painting, refused to sell it to me or to paint a more ambitious version of the theme, because, he said, it was not arte. He scoffed at the subject matter. Armando explained to me that the little sketch was an attempt to make a design for a Conjunto poster, but Hernandez could never finalize his vision for it. He told Armando it was “like a Beatles song where they have the tune, but not the words.” Hernandez eventually gave it to Armando.

Hernandez also indignantly recounted being invited to paint a fiberglass cow to be auctioned for charity at the “Cow Parade,” — as if Adan Hernandez would paint a fiberglass cow!

In 2002 Hernandez did, however, consent to being crowned King Huevo for the San Anto Cultural Art’s annual gala, alongside heiress and art patron Linda Pace (founder of ArtPace and Ruby City), who was dubbed Queen Huevo. The Huevos Rancheros gala spoofs San Antonio’s Fiesta, which celebrates Mexico’s defeat at San Jacinto on April 21, 1836 with Anglo American faux-royals and Mexican food, drink, music, etc. (I recently called for Fiesta to be decoupled from the battle of San Jacinto in a Glasstire op-ed.) In an article announcing the gala, Elda Silva noted that the huevos royals would be garbed in feathered robes and egg-shaped crowns, and that “subjects could press the flesh with the royals” for a dollar a dance (“Quirkiness goes over easy at Cultural Arts’ gala,” Express-News, October 11, 2002).

Adan Hernandez, a Western-themed painting the artist posted several times on his Facebook profiles. On June 14, 2016, he used the following caption: “The paintings I have to do to buy art supplies so I can keep painting my vision: Chicano Art!” I don’t know if this is the painting he referred to as a copy of a Remington (Armando says Adan painted a total of four cowboy canvases for the same patron). It looks closer to Combing The Ridges, by W. R. Leigh (1866-1955). For an image of the Leigh, go here.

Hernandez’s non-arte paintings did play a significant role in the development of his arte. Hernandez recalls painting a copy of the “cowboy” painting in 1986. It was his first oil painting. He told me: “I like the way oils let you think — because acrylics dry so fast you almost need to be an action painter.” Slow-drying oil paint, on the other hand, “let an image evolve on the canvas.” Oil permitted him to create complex works that were not pre-planned and not dependent on photographic sources. “I just knew it was the medium for me,” Hernandez said, “because that’s the way I work.” It only took one “cowboy” painting to change his approach to painting.

The experience of rapidly knocking out commissioned portraits also came in handy because Hernandez had to crank out numerous (the usual figure Hernandez gave was thirty or more) examples of arte for the film Blood In, Blood Out — as I’ll describe in Part 3. As noted above, Garza says the movie contract called for “about twenty canvases,” though Hernandez could have provided more than that number. Hernandez’s two-line statement in the Art of the Other Mexico catalogue concludes: “… Hernandez has produced an original, genuine body of work that has been said to represent ‘the essence, the spirit of Chicano art.’” This invocation of Rubeo’s comment summarizes Hernandez’s ambitions: he always wanted to be regarded as an original, genuine, and essential Chicano artist.

The Author’s Relationship with Hernandez

I taught at UT Pan Am in Edinburg for a year before moving to San Antonio in 1999 to teach at UTSA. Hernandez and Mel Casas topped the list of local artists I wanted to meet.

I met Hernandez in 2000, and spent a great deal of time with him around 2002-2004 refining his CV and developing two large, leather-bound portfolios that included photographs, slides, 4 x 5 inch color transparencies, and a few press clippings (I didn’t realized how much press he had garnered until I researched this article and unearthed dozens of additional stories). It was made to circulate among collectors, curators and galleries. I also hoped to find a New York gallery that would represent Hernandez, so that he could paint full time instead of working at other jobs. I thought that one of the top New York City galleries that handled self-taught artists could sell his major paintings for $60,000 or more, but Hernandez was unwilling to pay a commission on all of his sales (including those he made on his own), so that proved impossible. Hernandez was very excited when the portfolios were completely assembled, but that excitement turned to disappointment when every collector who saw a portfolio didn’t purchase a painting.

In 2004, I attempted to create an analytic chronology of Hernandez’s prime works, with substantial written commentary on each one. I then planned to interview artists, dealers, and collectors with whom he had interacted. I asked too many questions, and it was clear that — with few exceptions — I much preferred his earlier work. I didn’t get very far before Hernandez became frustrated and told me that he only wanted to talk about his current work, which he insisted was his best. (Paradoxically, in his last years, Hernandez was constantly reliving his Blood In, Blood Out period from the early 1990s.) I realize now that another reason for Hernandez’s reticence is that I would have discovered all of the inconsistencies in his bio that are noted in these articles. All of the unattributed quotes in these four articles are from my conversations and interviews with the artist, primarily from 2004.

Hernandez told me he had turned down an offer of an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum because he was the only Chicano artist in the collection, and he did not want to be a token. I replied that someone always has to be the first (both to be included in the collection, and to have an exhibition). I said that he could have refused the money from the sale of his works to the Met, or used it to set up a purchase fund for other Chicano artists. I discussed the museum’s importance, the impressive range of its collections, and how beneficial an exhibition of his work would be for the visibility and acceptance of Chicano art. Moreover, I emphasized how White the art world was in general. I noted that I was the first person from a protected ethnic group (Latino, Black, Native American) to get a PhD in art history at Berkeley (a university and city often regarded as crazy and radical in this country).

Hernandez then decided he did want an exhibition at the Metropolitan. On a trip to New York, I phoned a contact at the museum that Hernandez had given me. I explained that I was calling on Hernandez’s behalf, and that he very much wanted an exhibition. The woman gasped when I mentioned Hernandez’s name, and she did not seem eager to talk about him. I thought this was understandable, given the circumstances related to me by the artist. Though she did not question whether a Hernandez exhibition had been given consideration, I realize in retrospect that she did not explicitly confirm it, either. I’m now skeptical that he was offered an exhibition at the Met. (I’ll address this issue in the appendix to Part 2.) She was cold and guarded, and never called me back after our short conversation. I told Hernandez that we should try another museum.

I developed a Hernandez retrospective proposal called Adan Hernandez: Ladron de la Luz (Thief of the Light) that I ultimately submitted to the Museo Alameda, which opened in San Antonio in April of 2007. I received no response. Shortly thereafter, I moved to New York, and from there to Houston. In 2011, I toured an out-of-town museum director through Hernandez’s studio, but he did not like Hernandez’s work. I hope Hernandez’s paintings will, someday, finally get a museum exhibition.

I curated Hernandez’s work into several exhibitions, starting with Latino Expressions, an annual benefit for the San Antonio main library that I helped initiate. Co-curated with Arturo Almeida, Ellen Clark, and Angelika Jansen, the first iteration opened in April of 2004. I included two of Hernandez’s paintings in my Arte Contemporaneo exhibition at the Centro Cultural Aztlán (2004). I also included two of his paintings in The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Cente (2018).

I tried to get others to buy Hernandez’s work. I also circulated a review I wrote of the Cheech Marin collection in Voices of Art (2002) to my national contacts, as well as slides and photographs of Hernandez’s work. Some of these materials are preserved in the Tomás Ybarra-Frausto Research Material on Chicano Art in the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Hernandez was a popular guest lecturer in classes I taught at UTSA on Chicano art and film noir. It was a role he relished. We had many conversations about film posters, which I began collecting around 2005.

Hernandez had several books of film posters, and he quoted posters in his paintings in the form of billboards, handbills, and images projected onto drive-in screens. Posters — which suggest or compress a narrative into a single frame — also influenced the narrative structures of his paintings. It is no surprise that Hollywood film industry collectors recognized that his paintings were cinematic — his work engages film on many levels.

I’m curious how familiar Hernandez was with Mel Casas’ cinematic paintings. Casas’ Humanscape series (1965-1987) began with explicit images of drive-ins, televisions, and cinema interiors. Eventually, all of Casas’ subsequent Humanscape paintings included a “screen” image in the center (see my article “The Cinematic Genesis of the Mel Casas Humanscape, 1965 – 1967,” Aztlán, Fall 2011). I can’t think of any Chicano artists who were more deeply engaged with film imagery in their paintings than Casas and Hernandez. Casas had one-person shows at SAC (1982 and 1984), Arte Moderno Gallery (1988), the Laguna Gloria Museum in Austin (1988), and a 25-year retrospective at the Instituto Cultural Mexicano/Arte Moderno Gallery (1989) — all of which are local solo exhibitions that postdated Hernandez’s decision to become an artist.

Hernandez and Casas were in some of the same shows, including a show at Jansen-Pérez in San Antonio (1988) and the Tejanos exhibition (1990). Organized by Jansen-Pérez, the latter traveled to the Museo Carillo Gil in Mexico City. According to Goddard, Hernandez’s “night paintings” in the Tejanos exhibition were very atypical when the exhibition subsequently showed at UTSA, because some paintings were reserved for Blood In, Blood Out. He illustrates and describes Juan and His Ruca [girlfriend] Had a Close Encounter, which features a series of filmic panels that reference a recent UFO sighting (“‘Tejanos’ stakes a claim on CAM,” Express-News, July 14, 1991).

Hernandez always gave me a hard sell to support his art by purchasing his work. I ultimately bought three paintings, one of which will be discussed in each of the next three articles. The last was a replica of They Don’t Want Me in My House II, in which Hernandez depicted horror and film noir posters from my collection. Due to the circumstances related above, my knowledge of his work is unbalanced. I know a lot about a few paintings, and relatively little about the rest.

How Hernandez’s Experiences Shaped his Art

Adan Hernandez’s art reflects a distinctly South Texas experience of the racial and class disparities that he encountered in Robstown, Corpus Christi, and San Antonio. Hernandez was born on October 15, 1951 in Childress, Texas to a family of migrant laborers. I learned more about his family’s history in 2018. While I was preparing the catalogue for The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth, we discussed the history of deadly force used against people of color. Hernandez told me that his grandfather, Julian Hernandez, had emigrated from Mexico in 1910, at the start of the Mexican Revolution. He recalled that Julian had told him that Texas Rangers “killed Mexicans on sight.” This murderous violence, said Hernandez, forced his grandfather “to sleep in cemeteries, because they were the only places that the Rangers didn’t go.” He also said his grandfather told him that farmers would hire Mexican workers, and, after two weeks, murder them, “just so they wouldn’t have to pay them.”

When he was an infant, Hernandez’s family moved to Robstown, which he described as a sharply segregated “cotton-picking town.” The family shopped in the nearby city of Corpus Christi. With his eight siblings and parents, Hernandez worked primarily as a cotton picker. He recalls the camaraderie of working together as an extended family, and of feats of cotton picking performed by old men that no younger person could match. Pickers performed back-breaking labor; they filled large sacks, picking cotton with hands that were bloodied by the spiny parts of the cotton plant. “Chicanos were treated like slaves in Robstown,” Hernandez told me. He also emphasized that his paintings reflected his life: “my art is about experiences that shaped my life. It was shaped in the 1950s by powerful things, like witnessing a graceful and caring gente (people) endure the brutality of work in the fields.”

Mechanization forced Hernandez’s family to become urbanized: “when cotton-picking machines came in we lost our jobs and moved to San Antonio.” One two-row combine harvester could replace 80 workers. The family moved to San Antonio — relatives were already living there — when Hernandez was nine (which would be 1960 or 1961).

Hernandez told me he rejected agriculture as too hackneyed a subject for his arte, though he did include a large United Farm Workers button and an image of strike leader Emma Tenayuca on a painted tabletop he had in his studio in the early 2000s. Additionally, in Casa de Luto (House of Mourning, 1997), which Hernandez regarded as a premonition of his wife Debi’s death in 1999, he represents a sliver of a photograph of himself and a brother in a field (Goddard, “Chicano visionary Adan Hernandez’s art paints real picture,” Express-News, April 7, 2002).

Some artists who worked in the fields used that experience to make their most famous work, such as Ester Hernandez, a California artist I included in my last Day of the Dead exhibition. Felipe Reyes, the prime mover of Con Safo, emphasized United Farm Workers imagery during his time in the group. See my article Reyes 2 in Glasstire. If he had come into contact with Reyes at SAC in the early 1970s, perhaps Hernandez would have made farm worker-themed art. But his first serious attempt at an art career did not commence until the 1980s, when he deemed this subject matter passé.

I think Hernandez wanted to get as far away as possible from the cotton fields, so he transported himself to marvelously lit dreamscape cities conjured in part from films and fantasies. But he frequently included something he did associate with migrant labor in his paintings: palm trees. They flourish in the southernmost parts of Texas, and they are also present in San Antonio. For the artist, they have a special meaning: “When our family returned from migrant labor for Christmas, we were happy when we saw palm trees, because we knew that we were close to home.”

Many of Hernandez’s cousins were in bands that played conjunto music, which accounts for the prevalence of accordion players in his work. Jazz was commonly used in film noir, and never more dramatically than in D.O.A. (1950), which features a protagonist who was fatally dosed with an atomic cocktail in a San Francisco jazz club filled with White hipsters. He should not have left his seat to pursue that “jive-crazy,” fur-coat wearing blonde! Hernandez substitutes Tejanos for Black jazz musicians. Accordionists function as the demonstrative ethnic-others in the center of several of Hernandez’s paintings, including Hay un Rio.

In San Antonio, Hernandez participated in the student walkouts in 1968. He was an enthusiastic supporter of the civil rights movement, and of César Chávez. As noted above, he dropped out of high school and did not decide to become an artist until 1981. Hernandez told Bennett in the “Brillosos” article cited above that he didn’t have a painting sample when he sought a scholarship to SAC, so he successfully utilized his car, which he had painted “real psychedelic.” He told me the same story, though Hernandez qualified for and likely received need-based financial aid. Moreover, he would not have needed a painting sample to enter the community college. Hernandez told his brother Armando that the psychedelic bug got him the job at Atkins, though no one can attest to the veracity of that claim. However long he stayed at SAC, Hernandez does not credit the college with meaningful assistance in becoming an artist. Hernandez is regarded as a self-taught artist in San Antonio, and he also inspired other self-taught artists, including the sign painter Juan Farias, to become fine artists (Express-News, October 3, 2001).

Hernandez’s night paintings have much in common with noir films: they are dark and doom-laden, with unconventional angles and stylistic techniques that create unsettling, menacing, and entrapping scenarios. They also usually have complex narratives. Hernandez recognized his narrative connection to film, which he conceptualized in terms of race and class: “There is a lot of drama in my work. For years I wondered why I felt compelled to express that. Then I realized that the overcoming of adversity — the ‘drama’ which we love to celebrate in film — is a natural occurrence in the barrio. Gente (our people) have to struggle daily with the destructive forces of poverty.”

Hernandez referred to pachucos and their continuing legacy as “horas luminosas (luminous times, with the implication that they were short-lived) — the things that make a human being what he is.” He added: “I am still feeding off of this material.” While their work looks nothing alike, Cesar Martinez has consistently treated pachuco or pachuco-like character types (see my discussion in ¡Arte Caliente! Selections from the Joe A. Diaz Collection, 2004), so many examples of this kind of subject matter were readily available to Hernandez.

Trauma, Perspective, and Expressionistic Brushstrokes and Color

The fundamental shift in Hernandez’s work was a consequence of a confluence of factors in the latter half of the1980s. Hernandez told me it was triggered by his eighteen-month old daughter’s injury in 1985. (Garza dated it in early 1986 in Texas Monthly, which is likely accurate.) She pushed through a screen, fell from a second story window, and fractured her skull. The experience was traumatic for Hernandez and Debi; Gaza recalls they feared their daughter could suffer paralysis or brain damage, though she ultimately had no permanent damage. As Hernandez told Goddard in 1991, “I felt such tremendous guilt…To cure my insomnia, I began to paint all night” (Express-News, July 14, 1991).

Hernandez told me he made brillosos, which he described as “half-dark paintings” in 1988, before progressing to oscuros (completely dark paintings). He characterized his dark mode of painting as a “delayed reaction” to his daughter’s accident. According to Bennett (San Antonio Light, February 11, 1988), Los Brillosos (discussed in more detail in Part 2) was begun in September of 1987, and was being finished in February of 1988. Both versions of La Media Luna are dated 1988. Goddard described Hernandez as “a slow deliberate painter,” and noted that he took “several months” to complete the Media Luna canvas (“Blue Star III,” Express-News, July 24, 1988). Given this time frame, I wouldn’t be surprised if Los Brillosos was his only large brilloso. If the Met’s Bulletin was not referring specifically to Los Brillosos, he may have created other night scenes in 1987.

In any case, guilt and insomnia led Hernandez to paint at night, and ultimately to paint night scenes. He explained to me that the vertiginous, bird’s eye perspective present in works like They Don’t Want Me in My House II derives from memories of his tenancy in the Casino building, a stylish deco landmark building that was one of very few high-rise apartment buildings in San Antonio. High is a relative term, and anything higher than three stories in San Antonio was considered kind of high.

Hernandez told Goddard that “the flattened perspective” evident in his paintings “comes from looking out the windows of the Casino building, where everything seems stacked up right in front of you” (“‘Tejanos,’” Express-News, July 14, 1991). As a largely self-taught artist, Hernandez employed daring, unconventional, and anti-academic techniques. He didn’t have to learn how to break the rules, because he never learned them in the first place.

Carlos Almaraz, Echo Park Lake #1-4, 1982, oil on linen, 72 x 72 inches each, various private collections. Photo source: dunnedwards.com

His daughter’s fall led Hernandez to make dark night paintings from an elevated viewpoint that were colored by a fearful, anxious, and pessimistic psychological state. But where did the color and the loose, expressionistic brushwork come from? I think the best of the early night paintings were deeply influenced by Almaraz’s Echo Park suite, which is primarily a synthesis of Monet, Van Gogh, and various California influences. It was illustrated in a large foldout in the Hispanic Art catalogue. These paintings (which reproduced darker in the book than they appear here) show a dynamic range of color and lighting effects, from primarily dark on the left to primarily light on the right. The leftmost panel in particular demonstrates how visually exciting it could be to pierce dark fields with bright light, which in Hernandez’s hands became headlights, films, fires, neon, and television-lit windows in the night. Forms could be dissolved or agglomerated by rough, ragged brushstrokes, which, in Hernandez’s paintings, often communicate transience, danger, and psychological distress, just as they did in the hands of the German Expressionist painters in the early twentieth century. Implicitly, they convey the sense that there was no time or patience for careful draftsmanship, or for calm, deliberate, and exacting brushstrokes.

Almaraz’s paintings inhabited a completely opposite world. He freed color to become arbitrary and expressive: orange stars in the right three panels became mostly green in the left panel. Echo Park is a celebration of beauty, wonder, and love. Most of the people are romantic couples; they are paired in boats, by the side of the lake, on the bridge, and even as a bride and groom in the center, under what could very well be a statue of Venus. Almaraz transformed Echo Park into an Island of Cythera, from which one never has to disembark. The thick, textured palm trunks in the center even evoke Rococo columns.

Almaraz’s loose manner of painting arbitrary color was unlike anything Hernandez had seen before. In response, his painting technique relaxed. Brushstrokes darted to and fro — contours could no longer contain them. Sharp yellow and orange forms explosively broke up dark blue and purple masses — sometimes as literal explosions. Maximum contrast produced maximum explosiveness, maximum drama, and maximum emotion. The beautiful, curvaceous orange and yellow gestural brushstrokes that float and overlap on the surface of Almaraz’s lake were hardened and congealed into linear, geometric shapes, and sometimes transformed into explosive blasts (La Bomba, 1992) or twisted metal and broken glass (The Death of Chuey, 1991) that possess their own, terrible beauty. In La Bomba, the pointed blast rays that frame the man who is blown out of a skyscraper mimic the rays in the Virgin of Guadalupe’s mandorla — but his are rays of death rather than life. Almaraz’s erotic dreams of procreative rapture in nature devolved into dark urban nightmares of explosive and violent death.

Adan Hernandez, The Death of Chuey (El Picudo), 1991, oil on canvas, 60 1/8 x 60 inches, collection of Dr. Raphael and Sandra Guerra. Photograph courtesy of the National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago. Photo credit: Kathleen Culbert-Aguilar.