This is the first of three articles that discuss the early work of the San Antonio-based artist Felipe Reyes (b. 1944), who was the prime mover behind the Con Safo art group as well as the creator of a body of powerful, uncompromising, and influential political paintings in the early days of the Chicano movement, c. 1970-72. These paintings address: violence and other forms of discrimination directed against people of color; immigration and citizenship; the struggles for representation in government and for social services; efforts to reclaim culture and history; and the United Farm Workers emblem that galvanized and came to symbolize these collective struggles.

This article discusses Reyes’ painting Instant Genocide (c. 1971-2) and the police killing of journalist Rubén Salazar (1928-1970). In recent conversations, we discussed parallels between activism in the early days of the Chicano Movement and current activism related to the Black Lives Matter movement.

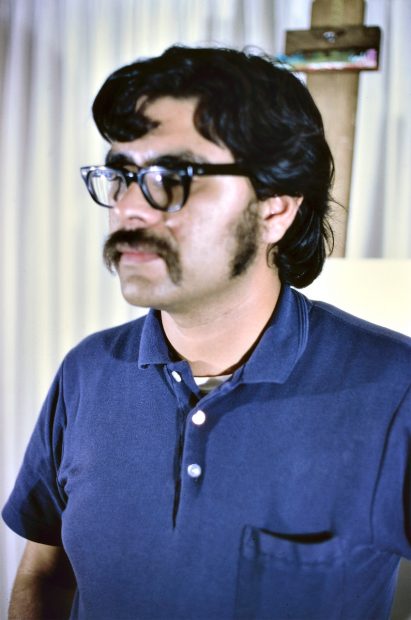

Felipe Reyes (b. 1944), c. 1971-2, with his easel in the background, San Antonio College. Photograph courtesy of Cesar Martinez.

“Chicano” was a self-designation used in the United States by activists of Mexican descent who were committed to social justice and social change. As noted by the Educating Change exhibition at Brown University in 2005, the Chicano movement consisted of several currents: the farm workers movement; the youth and anti-war movement that organized around school protests and walkouts and anti-Vietnam War actions; the struggles against discrimination and for political representation and power, including the Raza Unida Party, which originated in Texas; calls and struggles for the return of ancestral homelands in the Southwest that were taken from Mexico (often referred to as Aztlán, the mythic homeland of the Aztecs). For an overview of Chicano organizations and the movement’s leading figures, see Josue Estrada, Chicano Movements: A Geographic History.

Reyes was a member of one of the nation’s most marginalized and disenfranchised groups. Chicano consciousness and Chicano art were anathema to mainstream institutions such as museums, commercial galleries, and university art departments. Peaceful demonstrations and other anti-authoritarian manifestations were repressed in Texas, often with more violence than in other areas of the country. Moreover, the state’s official history celebrates the conquest of Mexico’s territory in quasi-religious terms, above all in the mythology surrounding the Alamo. [Please go here for a summary of the author’s interpretation of early Texas history.]

The CBS television program Hunger in America (first aired May 21, 1968) led Reyes to conclude that Chicanos in San Antonio were impoverished, marginalized, and segregated by design. This provided additional motivation to create trenchant and incisive works of art that gave expression to the Chicano experience and to the movement’s aspirations in a specifically Texan context.

The only group publication of these works appeared in Magazín (April, 1972), a short-lived Chicano journal published by Cecilio García-Camarillo (1943-2002) in San Antonio. It featured six paintings in black-and-white: Instant Genocide (discussed in this article); Todos Son Carnales, Sacred Conflict (to be discussed in Part II of this series); Pharr, Fast Buckaroo Politics, and The Rising Sun of San Juan (to be discussed in Part III). Most of Reyes’ paintings in these three articles are published in color for the first time. Magazín also featured an interview with Reyes by Carmen Lomas Garza in December of 1971.

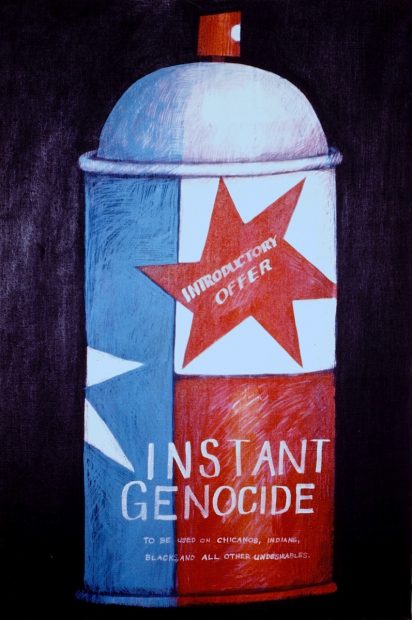

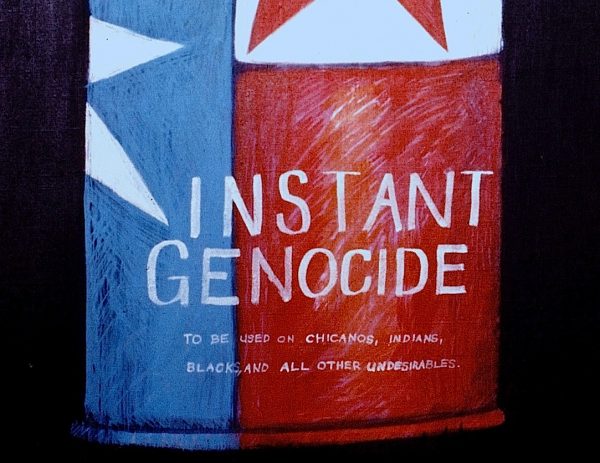

Felipe Reyes (b. 1944), Instant Genocide, c. 1971, acrylic on canvas, dimensions unknown (painting no longer extant). Photograph by Cesar Martinez. Reproduction courtesy of Tomás Ybarra-Frausto Research Material on Chicano Art, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Instant Genocide, or, if one prefers the equally caustic, alternative/ironic title, Peace on Earth, Good Will Towards Men, is Reyes’s most inflammatory and accusatory painting. This painting had an electrifying effect on everyone who saw it. The spray can’s design is a wrap-around Texas flag, which has a white star on a vertical blue field, and two horizontal stripes, one white and one red.

The reference is obvious to Texans, but not to someone unfamiliar with the state flag. Since the Texas flag mimics the U.S. flag, it can serve as a synecdochel reference to it: thus Instant Genocide alludes to both the state and the nation (and the state of the nation). Only two points of the white star are visible on the left, and the blue field continues (as a reflection) up the dome of the spray can. Reyes added an irregular red star (mimicking an applied sticker) with the words “introductory offer.” This faux sticker serves to emphasize commerciality. The presumption is that the buyer will be satisfied with the product’s deadly results, resulting in additional purchases to extirpate more ethnic people, implicitly characterized here as vermin.

“INSTANT GENOCIDE,” the product name, is emblazoned across the blue and red fields near the bottom of the can. Directions are specified in small print: “To Be Used on Chicanos, Indians, Blacks, and all Other Undesirables.”

Reyes was addressing violence perpetrated by security forces (police departments, sheriff’s departments, Texas Rangers, etc.) against people of color. In a recent conversation, Reyes observed: “The practice of killing people of color was widespread — it was particularly egregious in the South. Anglo-Americans took Native American lands and killed them. They took Mexican lands and killed them. They imposed slavery on Blacks and inflicted countless acts of violence. And yet they were not held accountable. They killed others with impunity, to gain wealth and to maintain power. It’s all about the money.”

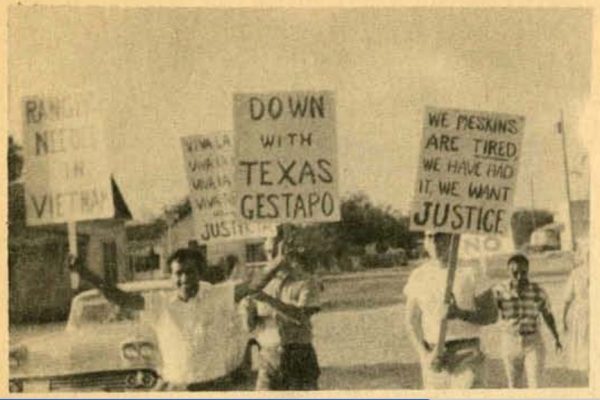

In Texas, the shock troops that performed the dirtiest of this work were the Texas Rangers. Founded by Stephen F. Austin to serve his slave colonies, Rangers eradicated Native Americans (Walter Prescott Webb called them “Indian exterminators”) and did slave-patrol duty. They subsequently terrorized, displaced, and dispossessed Tejanos and Mexican Americans. The Rangers tortured, lynched, and massacred thousands of people of color in the early twentieth century. After World War II, with a heavy concentration of KKK members, the Rangers prevented desegregation, brutalized union organizers, and ramped up their attacks on Civil Rights organizations. Though romanticized, eulogized, and idolized in mainstream Texas lore, Chicanos viewed Rangers as a white supremacist Gestapo, and their true history is finally coming to light. (See Sheryl Ring’s recent overview.)

Supporters of the farm workers strike in Rio Grande City, June 3, 1967. Signs include: “Rangers Needed in Vietnam” and “Down with Texas Gestapo.” Source: David M. Fishlow, ed., Sons of Zapata: A Brief Photographic History of the Farm Workers Strike in Texas, UFW,1967.

This recourse to violence was especially virulent in the Southern portion of Texas, where most Chicanos resided, often in communities where they formed disempowered numerical majorities. Historically, violence, the threat of violence, and other means such as poll taxes and voter suppression were required to subjugate them.

In his April, 1972 commentary in Magazín, Reyes spoke of the “institutional attitude towards Chicanos.” He was addressing social structures, and not merely individual prejudices. Reyes also pointed out that many Texans “are working to eliminate our culture,” which he characterized as “cultural genocide.” Reyes emphasizes that genocide can also operate on the level of culture, and not simply on the biological level. Years later, he experienced cultural hostility when he taught in an art department at the University of Texas at San Antonio that was deeply opposed to Chicano art.

During interviews conducted in the early 2000s, Reyes told me that he chose the spray can as a genocidal agent because it communicated “killing in an easy way,” which he likens to the pest extinguishment/removal of subhuman vermin. Reyes adds: “To many, we weren’t a ‘real’ threat, but a nuisance, like insects.” As reported in Texas Monthly, Ranger captain A. Y. Allee used similar language in federal court while denying that he had attempted to beat UFW organizer Magdaleno Dimas to death on June 1, 1967: “I could have killed him if I wanted to… I could have shot him three or four times before he got in that door… . If I wanted to kill him, I’d probably take a little Bee Brand insect powder and kill him. Hell, it won’t take much to kill him.” Allee had pursued Dimas, broken down the door, hit him with his shotgun, and kicked him while he was on the ground. Dr. Ramiro Raúl Casso called it “the worst beating I have ever seen law enforcement administer.” Part II will discuss the Rangers and the UFW in more detail.

Chicanos, Indians, and Blacks were the primary “undesirable” ethnic groups victimized by the putatively “civilizing” agents of Texas and the U.S., but this mock human pesticide stood ready for genocidal application to other groups, on an implicitly use-as-necessary basis. In this painting Reyes powerfully conveys the notion that racism is both deadly and systematic. “It’s structural — not accidental. And not due to a few bad apples,” he told me in a recent conversation.

In 2018, I thought of this painting when President Donald J. Trump explicitly called immigrants “animals” and when he utilized infestation rhetoric in reference to them. During a May roundtable in California, he declared: “We have people coming into the country … You wouldn’t believe how bad these people are. These aren’t people. These are animals.” Trump stated in a June tweet that Democrats didn’t care about immigrants who “pour into and infest our Country”:

“Democrats are the problem. They don’t care about crime and want illegal immigrants, no matter how bad they may be, to pour into and infest our Country, like MS-13. They can’t win on their terrible policies, so they view them as potential voters!”

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 19, 2018

In a June 19, 2018 article in the Atlantic, David A. Graham says in these two instances Trump mistakenly expressed “the quiet part loud.” According to Graham, Trump’s mask slipped, and by rendering his (usually) coded dog whistles explicitly, he revealed his racial animus.

Graham analyzes Tump’s rhetoric: “‘Infest’ is the essential, and new, word here. (Also popping up in the tweets is the older coded word ‘thugs.’) It drives full-throttle toward the dehumanization of immigrants, setting aside legality in favor of a division between a human us and a less-human them. What are infestations? They are takeovers by vermin, rodents, insects. The word is almost exclusively used in this context. What does one do with an infestation? Why, one exterminates it, of course.”

Reyes’ Instant Genocide is a critique of racism that encapsulates and embodies Trump’s racist rhetoric, though it was painted decades before these words were uttered.

Graham points out that Trump’s dehumanizing rhetoric leads to real policies, such as kids in cages. Reyes is highly critical of Trump’s family separation and child-caging practices. But if, from a Trumpean perspective, Latino immigrants are animals — or worse — then, at best, they belong in cages.

At its worst, dehumanizing rhetoric precedes mass murder. In a 2019 Psychology Today article titled “Human Beings are not Insects, Vermin, Parasites, or Garbage,” psychologist Pamela B. Paresky points out that Hitler, in Mein Kampf (published 1925-26), had referred to Jews by many disparaging terms: “like a harmful bacillus,” “bloodsuckers,” “vermin,” “vampire[s]” and “parasites.”

“When the Vermin are dead, the German Oak will again flourish,” cartoon signed Ru-pens on the front page of the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer, December 5, 1927. Source: German Propaganda Archive.

Nazis commonly referred to Jews as rats: explicitly, implicitly, and symbolically. Stephen M. Kellman, writing in Jewish Standard (August 30, 2014) points out that Hitler wrote that Jews were filthy and smelly, carriers of the bubonic plague, and suffered “a moral pestilence, with which the public was being infected.” Hitler also anticipated the final solution in Mein Kampf by writing that if 12,000-15,000 “Hebrew corrupters” had been subject to poison gas, Germany would not have lost World War I.

In the above cartoon, a Nazi fumigates a rat tunnel, killing several rats (representing Jews) and forcing others to flee. The cracked oak tree, labeled “Deutschland” (Germany) above an inscribed eagle, will heal and flourish, thanks to this Nazi fumigation. Reyes’ can of human pesticide, which is directly comparable to the imagery in this cartoon, thus finds its ultimate counterpart in the gas chambers of Nazi death camps.

The Nazi military commander Heinrich Himmler stated in 1943: “Anti-Semitism is exactly the same as delousing. Getting rid of lice is not a question of ideology. It is a matter of cleanliness.” Paresky cites psychologist David Matsumoto, who argues that when the emotions of disgust, contempt, and anger are combined, the potential for violence increases. Dehumanization, and particularly a subset we might call “verminization” provokes not only disgust and hatred, but also the fear of contagion. Himmler claimed genocide was hygienic; Hitler and others made similar suggestions. Aggressors who instigate pogroms and violence directed at dehumanized groups not infrequently characterize these measures as “defensive,” designed to protect or save one’s “superior” group from the dangers posed by diseased and disease-spreading “subhumans.”

Reyes argues that Trump “further harms Latinos by saying a border wall is necessary to ‘protect’ this country from them.” Trump’s demeaning comments and cruelty towards Latinos, coupled with his demands for a wall, serve to energize a “fascistic core” within his political base, says Reyes. As a consequence, “we need a strong Chicano voice to stand up to the policies of one of the worst political leaders that this country has ever had,” he adds. “But because Trump is a chronic liar, it is hard to keep him accountable.”

Excessive Force and Extra-Judicial Killings

On another level, Instant Genocide also addresses physical violence directed by police forces against leaders, activists, and innocent bystanders in Texas and other parts of the country.

In an extensive study titled “Lawless Cops, Latino Injustice, and Revictimization by the Justice System” (Michigan State Law Review, 2018), Lupe S. Salinas focuses on Latinos as he addresses police misconduct and accountability, and the “disproportionate violence” people of color have suffered “at the hands of law enforcement since times immemorial.” A Professor of Law at Texas Southern University, Salinas draws on his experience as a former federal prosecutor in the Southern District of Texas and as a Criminal Court Judge in Houston. Salinas also observes that the “extensive” mistreatment of Latinos has garnered “minimal” coverage by the news media. Chicanos suffered the greatest oppression in Texas, which is where their history has been most actively suppressed. Foundational histories of the Mexican-Chicano experience within Texas are still being written.

Rubén Salazar

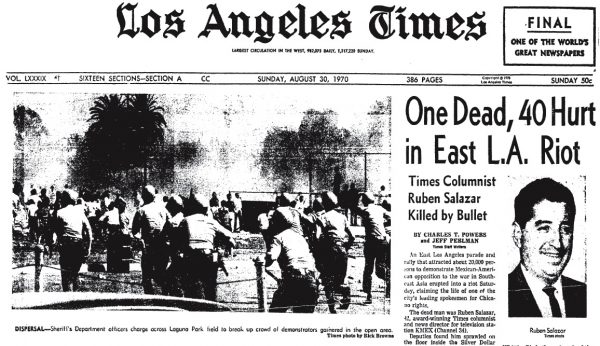

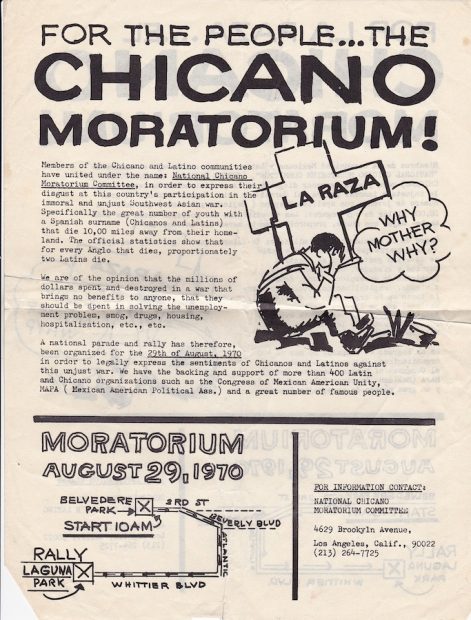

Of all the victims of police violence, Reyes was most concerned with the eminent journalist Rubén Salazar when he made Instant Genocide. Salazar had been a Vietnam correspondent and the Mexico City Bureau Chief for the Los Angeles Times. When he was killed, Salazar was the news director of the bilingual KMEX-TV station, and he still wrote a weekly Times column. Salazar and two young men affiliated with the Brown Berets were killed during the National Chicano Moratorium against the Vietnam War, which highlighted disproportionate Chicano enlistments and casualties. It took place in Los Angeles on August 29, 1970. Reyes — like most Chicanos — always believed that Salazar had been assassinated.

The following is a deep dive into the circumstances of Salazar’s slaying as we approach its 50th anniversary. It references materials that were not available when Reyes made Instant Genocide and when I first wrote about this painting.

Let’s start with the other two fatalities. Police said Angel Gilberto Díaz died when he ran a barricade, was shot by police, and crashed his car into a telephone pole. Journalist, activist, and Cal State Northridge professor Raúl Ruiz, in his three-part video, Mapping Truth: Following the Paper Trail in the Murder of Ruben Salazar (UCLA CSRC, 2012) says Díaz was shot in the back of the head through the rear window while he sat in the passenger seat. Witnesses attributed Lynn Ward’s death to an exploding tear gas canister; police claimed it was from a bomb planted by protesters. Ruiz, who notes that Ward’s head had multiple contusions when he arrived at the hospital, suggests that a beating by police caused his death. As is often the case, testimonies and evidence provided by people of color contradict accounts given by authorities.

The Moratorium can be traced back to 1969, when Rosalio Muñoz approached Ramsés Noriega and asked him to organize a Chicano anti-war movement. Noriega, a graduate art student at UCLA, had previously organized farm workers under César Chávez, and he had engineered Muñoz’s election as student body president of UCLA. They consulted diverse communities and eventually organized events in 20 cities throughout the Southwest and in Denver, Chicago, and Washington D.C. in preparation for what would be known as the National Moratorium on August 29, 1970. With estimates of 20,000 or more attendees, the National Moratorium was the single largest mobilization that took place during the Chicano movement. In recent interviews, Noriega told me 50,000 people had attempted to participate in the National Moratorium, but that police had only counted those who had arrived in the park when they ended the event.

Bill Drum, a friend of Salazar and a former reporter at the Los Angeles Times, described the movement as “a shaking off of this long-standing servitude. It’s like a volcano, and all of this cultural pressure that had been building up in Los Angeles these years finally burst through the surface” (quoted in Ruben Salazar: Man in the Middle, Phillip Rodriguez, director, PBS, 2014). The authorities sought to contain this eruption by repressing, disrupting, and discrediting Chicano organizations in order to crush the movement. Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) Chief Edward M. Davis was a “law and order” dirty trickster in the same league as his national contemporaries, President Richard M. Nixon and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. According to Edward J. Escobar (“The Dialectics of Repression: The Los Angeles Police Department and the Chicano Movement, 1968-1971,” Journal of American History, 1993), Davis was, next to Hoover, “the nation’s second best known cop,” and one with a similar arsenal of legal and non-legal methods he used against groups he disliked.

A complaint at a liquor store in the vicinity of Laguna Park (now Rubén M. Salazar Park) served as a pretext for authorities to move against the Moratorium and declare it an illegal assembly. It is unlikely they had any intention of permitting an authorized, peaceful demonstration to transpire. Rodolfo Acuña, in Occupied America: A History of Chicanos (1988), says armed police massed at the edge of the park, but did not communicate with event monitors. After some protesters “threw objects at the police,” an estimated 500 sheriff’s deputies and policemen moved in and attacked the crowd, even though the monitors had tried to restrain those who had thrown things. Acuña estimates that a force of over 1,200 officers terminated the after-march program soon after it had begun. Ruiz calls it “an assault” designed to suppress the “activist movement.”

Police forces have habitually attacked people of color when they exercise their constitutionally protected rights to assemble and protest, but have not used the same methods against the KKK, neo-Nazis, or right wing protesters and militias. In addition to punishing and intimidating social-justice protesters, authorities provoke them to resist — then they characterize the demonstrators as violent. Thus, instead of aggrieved citizens who could win sympathy and support, protesters are portrayed as threats to civil society. We have recently witnessed this phenomenon with the George Floyd protests, when authorities — all the way up to Attorney General William Barr — made false claims about protesters.

Before many in the Moratorium crowd knew what was happening, they were assailed with tear gas and beaten with billy clubs, including women, children, and journalists. Noriega, who was on the stage, told the men in the crowd to “hold the line” so that the women and children could escape.” Some demonstrators engaged the police to help others escape — many of whom were trapped against buses and fences. Noriega says demonstrators temporarily pushed the police back. But when the police broke through, they were enraged, and committed extremely cruel acts: “they hit women on the head with their clubs, and between their legs.” He adds: “Police threw teargas in bathrooms where children sought sanctuary.” The L.A. Free Press observed: following the “unprovoked attack… People grabbed children, knocked on doors of people living near the melee begging them to take in the youngsters for safety’s sake. Others ran for their lives… .” Many demonstrators were injured. Noriega estimates a thousand people were arrested, though most were not charged with crimes. Acuña notes that chained prisoners were maced multiple times. Noriega calls this repression “a police riot.” He says police, sheriffs, the FBI, the Treasury Department, and possibly other government agencies had “organized for months in advance to suppress it” [the National Moratorium].

Helicopters allegedly flew low and dropped tear gas canisters. I believe accounts of helicopters dropping tear gas (including the one in Wikipedia, which often proliferates erroneous information) are incorrect. Noriega says he never saw helicopters at the August 29 event, and he is certain that they did not drop tear gas. He says helicopters were utilized at subsequent demonstrations, and this is likely the source of the confusion. Other authoritative accounts do not mention helicopters on August 29. Few things — short of dropping napalm — could have done more to anger anti-Vietnam War protesters. Helicopters and tear gas were recently used against Black Lives Matter demonstrators in Washington D.C. Retired Naval Aviator Chris Harnes explains in The Drive why this use of helicopters is inappropriate, as well as dangerous to both people on the ground and crews who fly the helicopters. Ruiz, who was the co-editor of La Raza magazine, photographed a policeman utilizing a baton to choke and hoist a demonstrator, while another policeman laughed. This summons the choke holds police forces have used on people of color in recent years, sometimes with fatal consequences. Rioting began when the crowd was violently dispersed onto Wilshire Boulevard: parked police cars were attacked and businesses were burned. Chicanos contend that the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department (LASD) and the LAPD sought to provoke violence and that unnecessary brutality was the means by which it was achieved. This strategy is still employed by police forces today.

Angered by Salazar’s columns in the Los Angeles Times, police chief Davis had tried to get him fired. A prominent critic of police brutality at a time when the press routinely ignored it, Salazar was cautioned — sometimes in threatening terms — multiple times by the police, as noted by Robert J. Lopez in “Rubén Salazar had clashed repeatedly with LAPD in months before slaying” (Los Angeles Times, August 29, 2010). Salazar was continuing his investigation of evidence planting and excessive force by local agencies (the LAPD was a particularly notorious offender) in East L.A. Authorities were particularly riled by Salazar’s coverage of Guillermo and Beltrán Sánchez, two undocumented Mexican workers killed on July 16. Though LAPD detectives and San Leandro police had no warrant, they broke down a hotel door and shot five people — including one who was hanging from a window. They later claimed they had the wrong address. According to Salazar’s July 24 column in the Times, police — who were unaccustomed to criticism or oversight — told him “this kind of information could be dangerous in the minds of barrio people.” Following the fatal shooting of Breonna Taylor in Louisville, KY on March 13, 2020, public outrage could potentially end the practice of “no-knock” search warrants in the U.S.

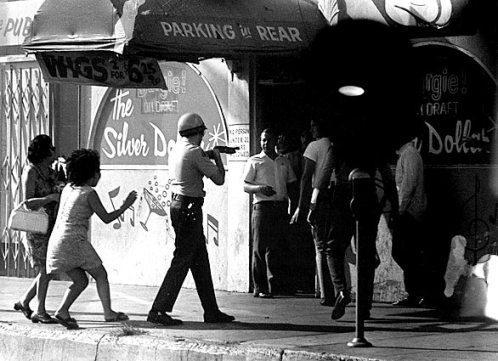

Salazar had stated to U.S. Civil Rights Commission officials that the police were following him and that he feared they would frame him for a crime. He thought he was being followed on August 29, when he departed Laguna Park and later entered the Silver Dollar café and bar on Whittier Boulevard, where he suffered a fatal through-and-through head wound. Police initially described it as a bullet wound.

Los Angeles Times front page, August 30, 1970, which states that Salazar was killed by a bullet in the Silver Dollar.

Hunter S. Thompson investigated the story when his friend, the activist attorney Oscar Acosta, told him the police “just murdered the only man in the community they were really afraid of,” and predicted no one would be tried for the crime. In “Strange Rumblings in Aztlán: The Murder of Rubén Salazar” (first published in Rolling Stone, April 29, 1971), Thompson detailed false claims: police initially said Salazar had been shot in Laguna Park, an account dutifully reported by The Los Angeles Herald-Examiner. Thompson characterized it as essentially the Fox News of its day: “a genuinely rotten newspaper… it serves a perverted purpose in its role as a monument to everything cheap, corrupt and vicious in the realm of journalistic possibility.”

After eyewitnesses and photographers with pictures testified to the contrary, authorities offered another story: following reports of gunmen in the bar, Salazar was killed by a 9 ½ inch, missile-shaped tear gas projectile. Both Thompson and Ruiz point out that this version also “makes no sense.” According to Ruiz, Deputy Sheriff George Grasser pumped his shotgun and used it to force bystanders into the Silver Dollar. Then Deputy Sheriff Thomas Wilson quickly fired two projectiles into the Silver Dollar, allegedly to force everyone out. Ruiz (who was across the street) and the people inside the bar did not hear any police warnings until long after Wilson fired.

Sheriff Grasser with shotgun (or tear gas gun) forcing men into the Silver Dollar (an action he denied taking). He subsequently forced the two women inside as well. Photograph by Raúl Ruiz. A cropped version of this photograph was used on the cover of a special issue of La Raza that appeared shortly after Salazar’s death.

The film Requiem 29, compiled by Moctesuma Esparza and David García and circulated as a videotape, features footage of the Moratorium and testimony at the non-binding Coroner’s Inquest into Salazar’s death that began on September 10. It includes discussions of the tear gas projectile and Ruiz’s photograph of the man being choked.

(For a profile of Ruiz with pictures, including a short clip of him being beaten by police at another demonstration when he tried to intervene on behalf of a girl who was being brutalized, see LinkTV.)

Deputy Coroner David Katsuyama with “Flite-Rite” tear gas projectile (a barricade penetrator not designed to be shot directly at people), testifying at Coroner’s Inquest, 1970. Katsuyama said Salazar’s head wound was consistent with the projectile. Screen grab from the film Requiem 29.

Police determined that Wilson had fired the fatal projectile. LACSD Sergeant Robert Laughlin subsequently fired two Flite-Rite tear gas projectiles into the Silver Dollar, and missed with a third. Ruiz also says he witnessed a deputy fire his .38 revolver directly into the Silver Dollar.

The inquest served to deflect blame for Salazar’s death away from Wilson and the police toward the demonstrators, as is evident in the Requiem 29 footage. They couldn’t smear this victim directly by dredging up evidence of a criminal record, drug use, etc. — tactics recently employed to defame George Floyd. So the authorities blamed Salazar by extension and implication: they said the demonstrators threw rocks and bottles, held Communist sympathies, etc. Chicanos denounced the inquest as a “sham” and as a “kangaroo court,” and Moratorium organizers refused to testify. No charges were filed against Wilson. Neither the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights nor the U.S. Justice Department took action on the matter. The County Board of Supervisors and the City Council had no Latino representatives. Chicanos were disempowered; there was no way to force a proper investigation. Salazar’s family, however, received a $700,000 settlement three years later.

Frank Sotomayor raised questions about Salazar’s death in 2010 in Borderzine, and he and many others called for the release of all documents pertaining to the case. In 2011, the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department allowed limited access to the files, which were finally released in 2012. The Los Angeles County Office of Independent Review issued a report titled “Review of the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department’s Investigation into the Homicide of Ruben Salazar” prior to the release of the documents. This OIR report, however, was mostly limited to the sheriff’s files.

Hector Tobar, writing in the Los Angeles Times in 2011, believes the killing was not deliberate because the coroner’s report said the fatal projectile picked up fibers from a curtain hanging in the entrance that were deposited in Salazar’s brain. Tobar therefore reasons that Wilson could not have aimed at Salazar when he fired the projectile. According to Jesús Salvador Treviño in Eyewitness: A Filmmaker’s Memoir of the Chicano Movement (2001), witnesses inside the bar saw Grasser or someone else move the curtains as Wilson prepared to shoot. Guillermo Restrepo, Salazar’s KMEX colleague, warned him that someone was aiming at them as they sat on stools near the Silver Dollar entrance. So the fibers alone do not prove Salazar wasn’t targeted.

Hunter S. Thompson, in the 1971 Rolling Stone article cited above, notes the police’s “incredible tale of half-mad stupidity and dangerous incompetence on every level.” He concludes that they were incapable of “staging an ‘accidental death’” via “a conscious, high-level cop conspiracy.” Thompson characterizes Salazar’s death as second-degree murder. But police forces that are not held accountable need not be particularly competent to get away with murder. The OIR report says Wilson didn’t have any idea who Salazar was, and had never fired a Flite-Rite before. But even if this was the case, someone could have said to Wilson, hey, that guy has been giving us trouble, why don’t you fire in his direction?

Ruiz sees a high-level conspiracy to follow and harass Salazar and to cover-up his murder, though he does not know precisely how he was killed. In 2011, the Los Angeles Times published documents from files on Salazar compiled by local and federal authorities that extend from the 1950s until shortly before his death. Ruiz doesn’t even believe the man he saw in the autopsy photos was Salazar. Nor does he think the large projectile caused his death, since Salazar’s brain weight was normal: “preposterous — was his brain made of butter?” Ruiz notes many inconsistencies, seemingly inexplicable actions, and an autopsy report with more questions than answers.

Treviño concludes: “We will never know the truth because of the way in which the inquest was conducted.” Even a proper inquest would not necessarily bring out the truth, since there is no reason to believe that the police would testify honestly and would not tamper with evidence. Noriega has no doubts: “Of course they killed Salazar on purpose.” If one thing is certain, it is that few Chicanos from that era will ever be convinced that Salazar’s slaying was accidental.

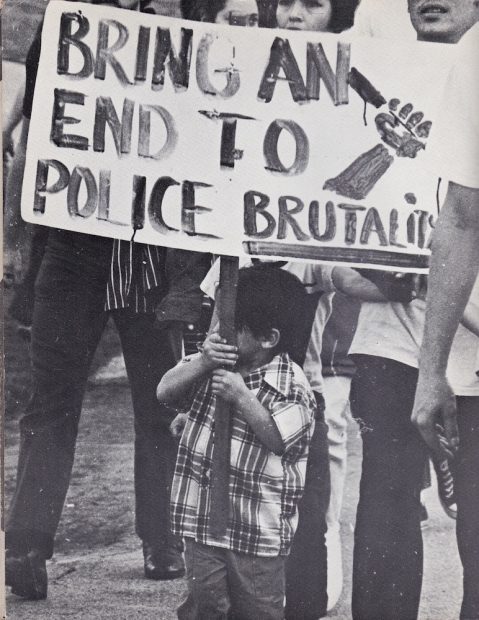

Child with sign at anti-police brutality demonstration in L.A., 1971, from La Raza magazine, photograph by Raúl Ruiz.

The later history of the Moratorium is instructive. The organizers’ offices were raided multiple times. A flyer produced in January stated that 52 members of the Moratorium Committee “have been arrested on false charges within a month.” As Thompson emphasizes, Salazar’s murder had a radicalizing effect: “the term ‘Mexican-American’ fell massively out of favor… . It suddenly came to mean ‘Uncle Tom.’” Thompson says consciousness changed with surprising rapidity, creating a before Salazar/after Salazar fault line.

An anti-police brutality demonstration held on January 31 that year was followed by a violent riot. A barricaded police station was barraged with rocks, bottles, and bricks. Police shot tear gas, 12-gauge shotguns, and revolvers. Nineteen people were wounded by buckshot and one was killed. Gustav Montag, an immigrant student, was struck in the heart by a ricocheted buckshot pellet. Several sources (including Wikipedia) incorrectly portray Montag as a police-fighter killed on August 29 rather than January 31. Ernesto Chávez, in ¡Mi Raza Primero! Nationalism, Identity, and Insurgency in the Chicano Movement in Los Angeles, 1966-1978 (2002) quotes Montag’s sister-in-law, who says he went out of curiosity, hoping to experience a riot. Tragically, he experienced more riot than he had bargained for.

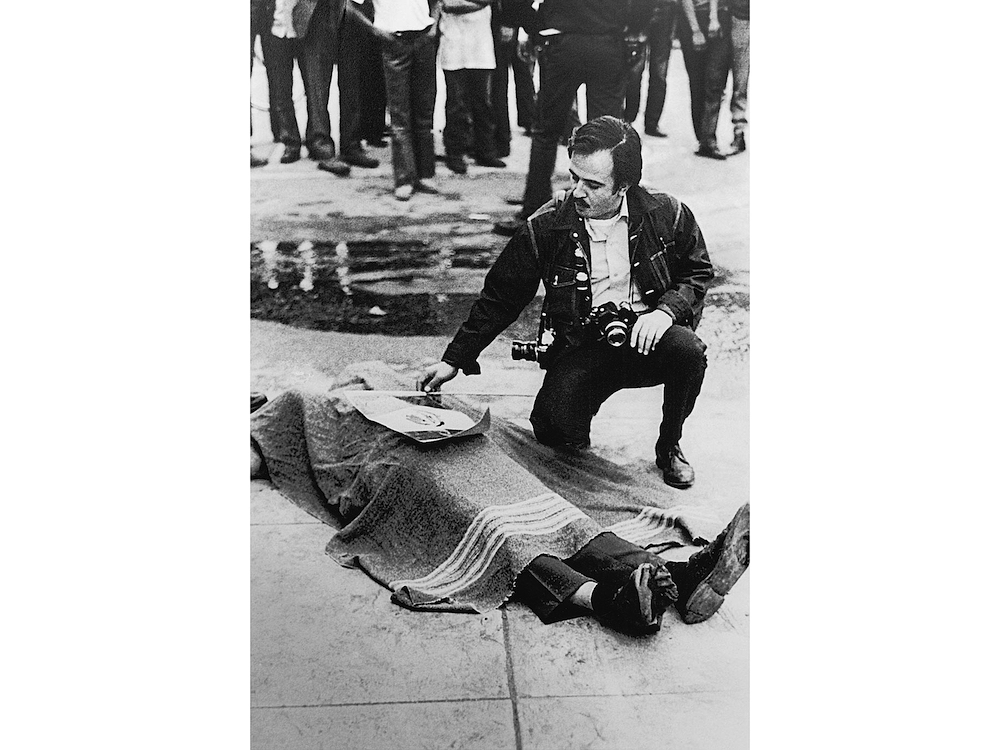

Raúl Ruiz placing a small Mexican flag on the body of Gustav Montag, a bystander killed after the anti-police violence demonstration, L.A., January 31, 1971. Photograph by Luis C. Garza.

Thompson notes the participation of angry, radicalized Chicanos who were unaffiliated with any political entities. Acuña points to the effects of heavy infiltration by police agents provocateur. Escobar argues that Chicanos were increasingly radicalized and that provocateurs caused violence. Moreover, the latter provided a feedback loop for the former: the subsequent exposure of the LAPD’s dirty tricks further served to enrage, radicalize, and motivate Chicanos. While the LAPD and other agencies sought to “destroy the Chicano movement in Southern California,” Escobar says these harsh tactics impelled Chicanos in other directions: “in voting, in litigating, and in developing new institutions that ultimately curtailed the power of the police to suppress legitimate protest.”

The Moratorium’s last breath came when Noriega surmised that disguised undercover agents had attacked a group based in Oxnard in order to provoke them to retaliate against the Brown Berets, and thus to provide a pretext for the National Guard to intervene. “I organized the Moratorium to be non-violent,” Noriega told me. He consequently disbanded the Moratorium out of fear that the authorities would cause more violence and death. Ernesto Chávez, in the book cited above, discusses this terminating incident in more detail.

Frank Martínez, a Moratorium leader who was one of the radicals who joined after August 29, subsequently revealed himself to be an agent provocateur. He confessed on January 31,1972 that he had been a confidential informant for the LAPD and the U.S. Treasury Department’s Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms. He also confessed that he previously infiltrated and informed on Chicano groups in Texas (MAYO and the Brown Berets). Agents provocateur also infiltrated other California Chicano groups, such as the Brown Berets. Escobar provides a substantial account of such infiltrations and other dirty tricks by the LAPD.

Salazar had been the only major journalist to attend Chicano press conferences. Pressured by authorities, KMEX ceased investigative journalism, and ceased giving voice to the Chicano movement immediately after Salazar’s death. In 1970-71, Chicanos in L.A. were isolated. As Ruiz observed during inquest testimony included in Requim 29: “…there’s nobody else who’s going to help [Chicanos], absolutely nobody.” Chicanos could not sustain mass anti-war protests in 1970-71 because they did not have sufficient means to withstand the waves of repressive forces unleashed by the state.

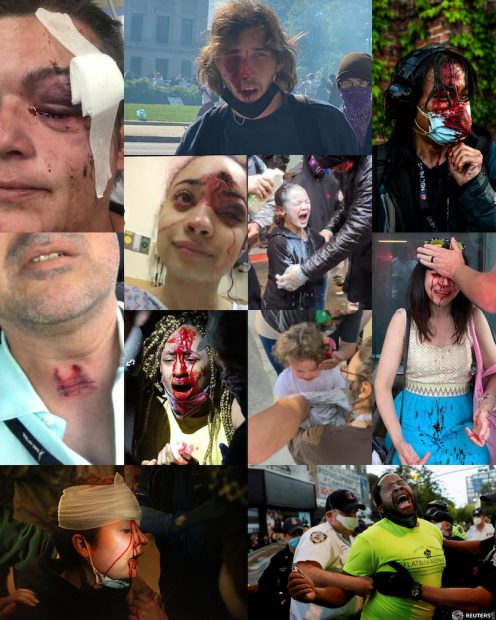

Montage of photographs of journalists, peaceful protesters, and bystanders brutalized by police forces at Black Lives Matter demonstrations, 2020. Compilation by Aaron McLain, Facebook.

Adolfo Guzman-Lopez, an L.A.-based radio journalist wearing press credentials, was shot in the throat by a rubber bullet in Long Beach on May 31, 2020 (he is in the middle of the left column in the above montage), just after he finished interviewing a Black man. Guzman-Lopez believes he was targeted because he is a journalist of color (they do appear to have been singled out in various police attacks nationwide). This experience made Guzman-Lopez recall Salazar’s fate; see the L.A. Times article by Daniel Hernandez. Hernandez notes “hundreds of attacks on journalists” covering demonstrations in the spring of 2020: The Committee to Protect Journalists is looking into 280 cases since May 29. Hernandez also notes efforts made to rein in police harassment and attacks directed at journalists, including a unanimous motion by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors.

Anyone participating in a Black Lives Matter demonstration — regardless of skin color — is at risk for unwarranted police violence. Amnesty International cites 125 instances of these human rights-violating abuses between May 26 and June 5 in 40 states and the District of Columbia. Amnesty International has called for systemic reforms “to ensure,” says the organization’s Brian Griffey, “that people across the country feel safe to walk the streets and express their opinions freely and peacefully without facing a real threat of harm from the very officers that are supposed to protect them.”

George Floyd’s recent murder at the hands of Minneapolis policemen is a uniquely catalytic event, with a deep, transformative effect. With each passing day, it seems the ground is moving ever swifter beneath our feet — and not as merely a garden-variety eruption. What was unimaginable just yesterday is happening today. We could be experiencing one of those rare seismic shifts that has the power to reshape the earth. The broad coalition allied with Black Lives Matter is well-equipped to successfully oppose the violence that has been directed against protesters and people of color since this country was founded. Cell phones, social media, and more diverse news media are providing instantaneous, hard-to-refute documentation. Without Darnella Frazier’s horrifying, lengthy video of Floyd’s murder, the police would have been unaccountable: they would not even have been tried. Already, in the wake of senseless violence directed against journalists and peaceful protesters, efforts are being made to defund and transform police departments, and to dismantle other mechanisms of white supremacy.

Felipe Reyes and I are hopeful that we have finally reached a tipping point at which widespread outrage at unwarranted state violence will force lasting, institutional change on many levels. “It’s about time,” concludes Reyes, who has been seeking these changes for more than 50 years.

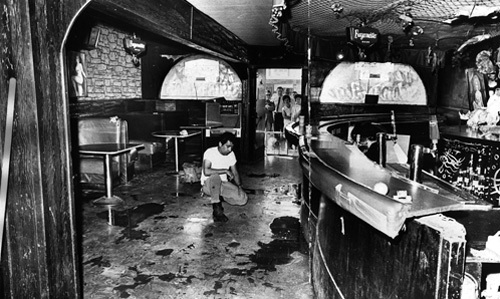

Silver Dollar interior, facing Wilshire Boulevard. Four tear gas canisters were shot into the Silver Dollar, though police did not enter it for two hours, despite being told that Salazar was still inside. Ruiz says the tear gas would have killed everyone in a matter of minutes, had they not been able to flee out the back door. Source: Los Angeles Morgue Files (an internet site), no photographer credited.

****

Part II of this series will center on the United Farm Workers and Reyes’ paintings that feature UFW imagery, including his landmark re-assessment of the Alamo.

Part III will examine how police violence — including a fatal shooting — led to Chicano political empowerment in the Rio Grande Valley. It also discusses art relating to political struggles in San Antonio.

****

My thanks to Bill Fisher for providing digital scans of the two pertinent issues of Magazín. My discussion of ‘Instant Genocide’ incorporates material from my book ‘Con Safo:The Chicano Art Group and the Politics of South Texas’ (2009).

****

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator. He has written extensively on the Con Safo art group, and he has curated ten solo exhibitions by group members, including Reyes’ “Barrio Dogs and the Cholo Landscape” (2006).

3 comments

Amazing work! Excited for Parts 2 and 3!

Thanks, Neil. We live in very interesting times! In Part 3 I will discuss the anti-police brutality protests in Pharr, Texas in 1971. After a bystander was shot and killed by police, the protesters were made up of women, because it was assumed that police would not dare beat them or shoot them. I see a parallel with the Wall of Moms in Portland, organized to shield the other protesters. By sending his troops (against the wishes of the governor and mayor), Trump went far beyond his incremental, creeping authoritarianism–it was a giant goose-step in that direction. Since they have used tear gas and “rubber” bullets on the moms in Portland, these troops have unleashed violence on peaceful female demonstrators that even the South Texas forces (police, sheriffs, and Texas Rangers) restrained themselves from utilizing.

I made a query about the Nazi ‘Ru-pens,” whose illustration I used in this article. Rama Dev discovered that it was a pseudonym for Philipp Rupprecht. Dev cited an article (“Searching for the next Philipp Rupprecht, Illustration Art, May 11, 2016) and a German language book (Literatur, Film, Theater und Kunst, 2014, p. 447-48) that are both accessible online. Rupprecht resembles the Nazi exterminator in the illustration sufficiently for me to wonder if it is a self-portrait.