Para leer este artículo en español, por favor vaya aquí. To read this article in Spanish, please go here.

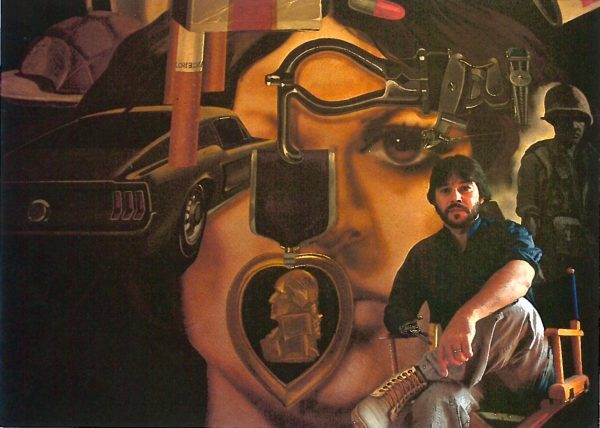

Jesse Treviño, San Antonio’s best-known artist, arguably possesses the city’s most dramatic biography. Were his life’s story presented as fiction, it would probably be judged laughably implausible, a likelihood that confirms the maxim that truth is sometimes stranger than fiction. The focal point of this essay is Mi Vida (1971-72), an 8-by-14-foot autobiographical mural painted on the artist’s bedroom wall, which is recognized as a key monument of Chicano art. It was the title piece of Treviño’s retrospective held at the Museo Alameda in San Antonio in 2009-2010.

Treviño was born in 1946 in Monterrey, Mexico. His family moved to the San Antonio area four years later. In his youth Treviño won numerous art competitions, culminating in a scholarship to the Art Students League in New York in 1965. After a year, Treviño was drafted and deployed to Vietnam, where he suffered grievous injuries in early 1967: a shattered femur and a severed artery from a sniper’s bullet, as well as ten shrapnel wounds from a booby trap whose blast threw him twenty or thirty feet. Immobilized in mud and bleeding profusely, Treviño expected to die in that Vietnamese rice paddy. But he vowed that if he lived he would return to San Antonio rather than New York, where he would paint the people and places that were dearest to him. Thus Treviño’s determination to become a Chicano artist was born in Vietnam, in a literal baptism of fire. After returning to San Antonio, he would fight another war — a still-ongoing cultural war — to win acceptance for Chicano art.

Against all odds, Treviño survived. He was pieced together with 350 stitches, though the wounds he suffered in Vietnam ultimately led to the loss of his right hand and forearm, so he learned to paint with his left hand. He eschewed the painterly style that he had developed in New York and became a photorealist painter, one so accomplished that Michael Ennis, writing in Texas Monthly called Señora Dolores Treviño (1982) “one of the best paintings of an artist’s mother since Whistler’s.”

Treviño devoted his life to art: he spent every available moment making art. But his wounds had rendered his right arm and hand useless. Severed nerves caused chronic pain: “My arm felt like it was on fire. It burned. The pain was like pins and needles. I couldn’t move my right hand.” Three major operations and physical therapy were of no avail. These medical failures caused the artist to fall into a state of despair. Armando Albarran, who had been drafted out of high school and lost both of his legs in Vietnam, was a fellow patient at the Beach Pavilion at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. He visited other wounded veterans and attempted to raise their morale. When Albarran learned that Treviño was an artist, he repeatedly urged him to paint his portrait with his left hand. It was his way of trying to help Treviño cope with his losses and move on to the next phase of his life.

Treviño had no desire to work with his untrained left hand, since he had spent his entire life enhancing the facility of his dominant hand. Moreover, the mere act of holding a brush in his left hand caused excruciating pain in his right. But after about a month he finally succumbed to Albarran’s incessant entreaties, concluding that it was the only way that Albarran would ever leave him in peace. The materials to make oil paintings were readily available as occupational therapy supplies. The portrait of Albarran in his uniform that Treviño painted at Fort Sam Houston in 1968 was the first artwork that Treviño made with his left hand.

The small portrait took a week or two to complete because Treviño struggled to overcome pain while he painted. He recalls that painting with his recalcitrant left hand “was like getting someone to do something that had a bad attitude.” But in retrospect, he acknowledges that without Albarran’s persistence, “it might have taken me a lot longer to do my first [post-Vietnam] painting.” Albarran subsequently became a rehabilitation specialist for the Veteran’s Administration. (Albarran’s tireless efforts to rehabilitate wounded veterans were recognized when he was elected national commander of Disabled American Veterans in 2000.)

Treviño didn’t execute his next painting, Alamo Exit, until 1969, but it was exponentially more sophisticated and technically superior to the Albarran portrait. Now enrolled at San Antonio College (SAC), he was assigned to paint a modern landscape. Treviño chose to emphasize the human-built environment: the countryside peeks through beneath a highway underpass. The latter’s stark, black-silhouetted forms impart an abstract quality. Fragments of four letters on a highway sign are sufficient to convey the word “Alamo,” endowing the landscape with a highly specific geography. In his immediately succeeding works that paved the path to Mi Vida, Treviño made continued use of synechdoche and symbolism. This is the only painting before Mi Vida that utilizes a black ground.

Treviño retrospective exhibition installation; photo by Ruben C. Cordova. Pictured: Alamo Exit (1969, acrylic on canvas, 2 panels, 32 x 42 inches each, collection of the artist) is on the right; Zapata (1969, acrylic on canvas, 99 x 36 inches, collection of George Cortez) and Armando Albarran (1968, oil on canvas, 24 x 18 inches, collection of Armando Alabarran) are to the left of Alamo Exit.

Educator Mia Lopez videotaping Ruben C. Cordova at Treviño retrospective at Museo Alameda, 2010. Paintings (from left to right) are Armando Albarran (1968), Zapata (1969), Alamo Exit (1969), and Mi Vida (1971-72).

Fascinated by examples of unconventional artworks made by Pop artists, Treviño wanted to make a shaped or non-flat canvas, so he made Alamo Exit from two identically sized canvases, which are usually set at a 90-degree angle. In Treviño’s retrospective in 2009, I hung the painting in a convex configuration: the panel with the exit sign faced directly across from Mi Vida. In 2018, in the The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth exhibition at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, I hung the painting in a corner, in a concave configuration. Treviño wanted the panels to be displayed in other ways, including on opposite walls, where a spectator could view only one panel at a time.

TIAC (Pontiac, 1969) evolved out of an assignment at SAC to make a painting that included a real object integrated into the fictive space of the artwork. As his object, Treviño utilized the outer grill of the Pontiac GTO, the quintessential muscle car of the late 1960s. The artist recalls: “I wanted the car to appear as though it were in a dealership — as if the viewer were looking through the window.” A commercial sign painter rendered ‘TIAC’ (the last four letters of Pontiac) on the outside of a framing glass box. Treviño and many of his fellow students were active in the Chicano movement; Treviño alluded to Chicano identity by drawing a slanted line after the “c” and added the letter “s” to form C/S, which is the abbreviated form of Con Safo, the Chicano equivalent of King’s X. He also utilized the letter “c” to spell out the name “chuy” — as if someone had scrawled his name graffiti-style on a showroom window. In this work Treviño employed several forms of synecdoche, including the title, the grill, the chuy graffito, and the C/S inscription. Treviño would join a Chicano art group in December of 1971, right when it adopted the name Con Safo.

Zapata (1969) is the product of an assignment in a class taught by Mel Casas at SAC. Casas instructed his students to render a hero, an anti-hero, and a villain in a single painting. Treviño chose the Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata as his hero. He painted the entire canvas red with an aerosol spray can in order to create a vibrant background. The heroic figure of Zapata was made with black spray paint, largely freehand, though some areas were masked off with tape. Zapata dominates the vertical axis. As his villain, Treviño chose Vice President Spiro Agnew, the self-proclaimed voice of the “silent majority” and proponent of “law and order.” Agnew served President Richard Nixon by denouncing the press, protesters, and the Democratic opposition, sometimes with bizarre phrases invented by his speechwriters, such as “pusillanimous pussyfooters” and “nattering nabobs of negativism.” Agnew became popular in conservative circles. A Spiro Agnew wristwatch (a parody of the Mickey Mouse watch) was manufactured to capitalize on his ephemeral celebrity. Opponents as well as supporters of Agnew purchased it. The Agnew watch did double-duty because Treviño regarded both Spiro Agnew and time itself as villains. As the artist put it: “Time flies, preventing you from doing things.” As the anti-hero, Treviño chose the food stamp. He acknowledges that food stamps are “great for the people who really need them, but not for the ones who abuse them.” The food coupon appears to wrap around the canvas. The three elements are intended to cause the viewers’ eyes to move in different directions. Rather than providing the large painting with a frame, Treviño utilized a thick support and painted “all the way to the edges to make the painting like an object.” The utilization of spray paint and large collage elements also served as important precedents for Mi Vida.

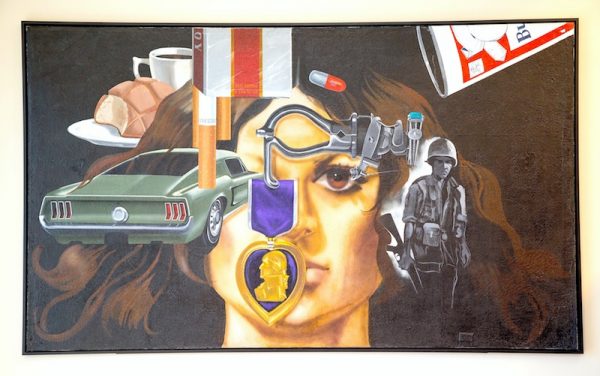

Jesse Treviño, Mi Vida, 1971-72, acrylic on gypsum board, 8 x 14’, collection of Inez Cindy Gabriel, photograph courtesy of City of San Antonio

Mi Vida

Treviño made the heart-rending decision to amputate his upper right arm in November of 1970. Years of efforts to rehabilitate it had failed. He hoped — at the very least — that amputation would end the pain. It did not. The phantom limb burned just as much as the real one had. His disappointment compounded the debilitating nerve pain. But at least Treviño knew that he could make real art with his left hand. Initially, he had only hoped to become a left-handed teacher of children. Now he was determined to become a successful artist. It was the summer of 1971, and Treviño had not attempted to create any art in the six months since the amputation. During this period of deep despondency and deep introspection, he painted the wall across from his bed black. This is how Mi Vida began.

The black ground emulated the working process of Mel Casas, the chair of the SAC art department, who would also become the president of the Con Safo art group (both Casas and Treviño joined in late 1971). Casas painted a series of black ground canvases known as Humanscapes, from 1965-1989. For Treviño, the black ground had symbolic meaning: in an era of Black Power and Brown Power, he thought it was significant to begin with black instead of white.

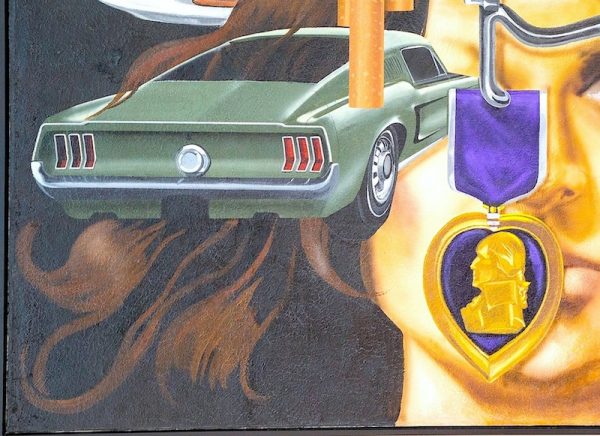

Treviño isolated himself in his room, which he rendered completely dark by boarding up his window. There could be no distractions. Then he mounted two spotlights on the ceiling (equipped with dimmer switches) that he directed at the black wall. Treviño blasted classic rock on his high-fidelity stereo as he stared at the wall and reflected on his life. He played with the lights for about a week, until he had conjured a monumental vision of his prosthetic arm. He painted it. Once he had started on the arm, he saw the Purple Heart medal. He painted it, too. Then he embellished the wrist area with the silver and turquoise bracelet. These three metal objects weld in the mind’s eye into a single, uncanny object, suggesting a robotic or biomechatronic substitute for the human. At the same time, they retain individual symbolism. The Purple Heart is awarded to members of the military who are wounded by the enemy. The medal bears the image of George Washington, the ultimate founding father (both militarily and politically). As the mythic “Father of Our Country,” he also represents an era when only white men possessed full rights in the United States. At the same time, military service conferred citizenship on Treviño (which is one reason he served in Vietnam, rather than returning to a Mexico he could scarcely remember). So, in a very real sense, it represents becoming “American.” The prosthetic arm is a substitute for Treviño’s real arm, rendered useless by his war wounds. It represents all that he lost in Vietnam, as well as all that he gained: citizenship, a new commitment and orientation in his artistic practice, a new car. The silver and turquoise bracelet was a gift from a young woman named Joanna. Materially, it can also represent the indigenous and the Mexican. The bracelet is also a token of continuity and normalcy. Though Treviño never wore a bracelet on his “real” right wrist, he affixed this bracelet to his prosthetic right wrist with epoxy.

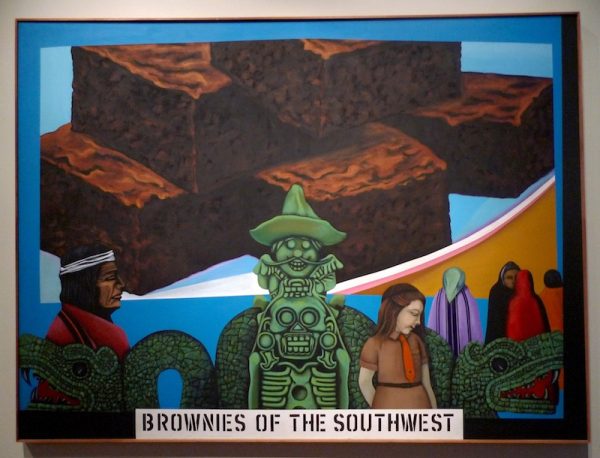

Trevino’s agglomeration of these three central elements has a direct and equally astonishing precedent in Casas’s masterpiece, Humanscape 62 (Brownies of the Southwest, 1970).

Mel Casas, Humanscape 62 (Brownies of the Southwest), 1970, acrylic on canvas, 6 x 8’, Smithsonian American Art Museum, photograph by Ruben C. Cordova

In Casas’ painting, a double-headed serpent mosaic (Quetzalcoatl), an Aztec skeletal figure (identified by Casas as Xolotl, Quetzalcoatl’s deformed, monstrous twin), and the Frito Bandito — all of which are rendered in a greenish jade-like hue — seem to coalesce into a single, mind-blowing sculpture. The Frito Bandito (the ultimate crass Mexican racial stereotype of its era) even seems to ride Xolotl like a horse. Xolotl’s hair resembles the horn of a saddle, and his earrings can even read as the Bandito’s tiny boots. But as monster rides monster, the Bandito’s comic grin is an asinine reflection of Xolotl’s death grimace. Quetzalcoatl represents art, learning, culture, and the forces of life. As his dualistic opposite, Xolotl represents the equally important forces of death. The Frito Bandito is likewise the antithesis of Quetzalcoatl: he is an embodiment and agent of stupidity and ignorance.

Jesse Treviño, Mi Vida, detail, 1971-72, acrylic on gypsum board, 8 x 14’, collection of Inez Cindy Gabriel, photograph courtesy of City of San Antonio

Some weeks or months later, Treviño added the nearly life-sized soldier who grasps his M-1 rifle, just as Treviño did when he was wounded. This ghostly self-portrait — as if summoned through the fog of memory and war — lacks the color and substance of real life. It is roughly sketched in white and gray, specifically to situate it in the past. Treviño observes: “…it was already behind me; the other things were in the present.” Eerily, the prosthetic arm almost seems to spring from the soldier’s head.

In the fall of 1971, Treviño began taking classes at Our Lady of the Lake University. While working on his class assignments, he gradually added one autobiographical element after another to Mi Vida.

As Treviño stared at the wall, he saw a vision of Joanna, the young woman who had given him the turquoise bracelet. She had recently attended a Con Safo meeting at his house. Eventually, Treviño added her portrait under his mechanical hand, rendering her head nearly the entire eight-feet height of the wall. As Treviño painted her left eye, it evoked one of his most vivid memories from his Monterrey childhood: he had witnessed an enormous eye that was being painted on a billboard. Ironically, Treviño’s prosthetic arm almost seems to be holding Joanna’s eye open, like the mechanical device in the film A Clockwork Orange.

Jesse Treviño, Mi Vida, detail, 1971-72, acrylic on gypsum board, 8 x 14’, collection of Inez Cindy Gabriel, photograph courtesy of City of San Antonio

Treviño subsequently painted a Ford Mustang on the left side of the wall. Both the car and the mechanical hand cast shadows on Joanna’s face. The medal and the car (the latter seems to be jutting out of Joanna’s eye socket, or — more malevolently — crashing into her face) take the place of her right eye. We should see part of the eye, but Treviño omitted it because that area would be otherwise too congested. Treviño repainted her hair, to make some of the locks flow over the rear of the car. The hair even seems to be inside the car, which appears to be hollow — there are no seats or other interior elements. This emptiness endows the car with an eerie, spectral quality that balances the ghostly self-portrait on the other side. Treviño had always wanted a sports car, and his disability pay enabled him to buy a Mustang in 1968. Many young men figuratively declare they would “give their right arm for a Mustang” and that was precisely the cruel price Treviño paid for his. Sports cars like Mustangs are a central component of the adolescent American Dream, associated with “cruising” and dating. Treviño had never had a girlfriend, so he had missed out on these rituals. The artist eventually extended Joanna’s streaming brown hair to the lower corners of the picture. Treviño rendered these areas in a particularly painterly manner, a technique that harkened back to his New York period. The hair, in fact, seems to take on a life of its own, replete with the power to coil and ensnare. The artist recalls using airbrush on the hair, though he worked most of the painting’s visible surface by hand (the black ground has been rolled, probably with latex) with professional artist paint from tubes — many, many tubes. His intention, however, was to emulate the appearance of airbrush.

Treviño later added a pack of Viceroy cigarettes, which he smoked habitually. Three cigarettes are falling out of the pack that floats upside down near the top of the painting. One cigarette eclipses part of the Mustang. After the cigarettes, Treviño painted some pan dulce on a plate and a cup of coffee in the upper left, behind the woman’s hair. These various overlapping forms create strong rhythms and impart layered complexity. Treviño painted an upended can of Budweiser beer in the upper right side. It seems to pour its contents directly on the soldier directly below. Finally, near the upper center of the painting, Treviño added a Darvon pain killer. His doctors had prescribed these pills, though he says they did “more harm than good” (and are therefore analogous to the food stamps in Zapata). Treviño had utilized all of these chemical substances in an effort to combat excruciating pain, which is why they carry such a potent charge, giving them more in common with Surreal objects than Pop objects. This hallucinogenic combination of floating objects appears to be connected and disconnected at the same time. The cigarette package, beer can, and pill even share a red and white color scheme.

If the objects accumulated in this painting now constitute a retrospective reflection on the artist’s life, they also seem like a surreal, premonitory vision experienced by the ghostly soldier. As fate would have it, Joanna was killed in an automobile accident without ever having seen the painting, which puts a macabre spin on the American Dream. The Mustang crashing into her face seems to presage her own fatal car crash. It might even seem as if she is kissing the Purple Heart: a kiss of death as she bids adieu to this world. She survives as a face she never saw, haunting a bedroom wall, a screen onto which other ghostly objects cast their shadows. This is a phantasmatic painting, haunted by memories and premonitions of injury and death, of battles lost and battles won, both past and future.

Soon after completing Mi Vida, Treviño resolved never to paint anything that wasn’t readily transportable. He estimates that only about 50 people saw the painting in his bedroom. When Roberta Smith, the current co-chief art critic of the New York Times spent twelve days surveying art in Texas in 1976 for Art in America, she was “particularly moved by a large mural executed on a wall in Treviño’s home concerning his experiences in Vietnam.”

Mi Vida was publicly exhibited for the first time in 2009-10 at the Museo Alameda. It is currently on view at the Henry B. Gonzalez Convention Center in San Antonio, which is only the second place it has been exhibited. Mi Vida will soon be shipped to Washington D.C. for Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965-1975, an exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum that opens March 15. Hopefully Mi Vida will some day be on permanent display in an appropriate locale.

***

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator. He curated the Treviño retrospective at the Museo Alameda in 2009 and he presented Treviño with his award at the City of San Antonio Department of Art and Culture’s Distinction in the Arts celebration in 2016. Cordova served as a consultant to the city of San Antonio for the purpose of placing and interpreting art at the Henry B. Gonzalez Convention Center in 2017-18. He recommended the purchase of Casas’ ‘Humanscape 62’ (‘Brownies of the Southwest’) to the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and he has advised the museum on exhibitions. His publications include ‘Con Safo: The Chicano Art Group and the Politics of South Texas’ (2009), which was the first book published on a Chicano art group.

3 comments

This artwork spoke louder to me than what my eyes were viewing. Beautiful. Absolutely beautiful

Absolutely compelling and beautiful. What a man. Wish I could have met him.

I appreciate the extreme difficulty of recovering from such a huge debilitating injury; and then mastering painting! Truly amazing. I was fortunate to have exhibited with Trevino during Blue Star 10 in the 90’s.