The land of the dead is a land of flowers and abundant food.

-Leslie Mormon Silko, Almanac of the Dead

The Day of the Dead in Art, curated by independent art historian, Dr. Ruben C. Cordova, and presented by the City of San Antonio Department of Arts & Culture at Centro de Artes, opened on October 24, 2019, and closed on January 19. This remarkable exhibition explores Day of the Dead as a social art practice through over 100 art objects made by more than 50 artists, many from Texas and most of whom are Mexican or Chicana/o.

There is an abundance of notable works of art in the exhibition, both vintage and newly minted. Dr. Cordova provides ample introductions to each thematic section and a clear narrative throughline for the exhibition. The foyer is adorned with visually stunning folk art, intricate ceramic sculptures that capture the essence of the liminality between life and death. The work of Alfonso Castillo Orta exemplifies this theme in Skull with Cactii and Figures (2003). A cactus sprouts from an ornately painted scull, which is crawling with creatures, living and dead. Artistic responses to the apocalypse enclose the exhibition like a ring of fire. It begins with images that reference Christian prophesies of the end times and circles back to this theme with artwork representing contemporary threats to humanity, such as climate change, mass shootings, and political and moral corruption.

Alex Rubio’s spectacular panels, The Four Horsemen (2006) [picured at top] is a revelation to behold. The skeletal Horsemen are not on the gallop, but are instead interred in crypts resembling twisted relics of evil and doom, each representing a particular malady — Pestilence, Famine, War, and Death. But Rubio also captures the purpose of purification at the heart world-ending destruction. Each of the crypts also holds a remedy to counteract the evil contained within it. The circular exhibit hall brings the visitor back to the foyer where a corollary to Rubio’s horsemen awaits. The Second Seal (2018-19), by Albert Alverez, reimagines the henchmen as General Robert E. Lee and other white nationalist evildoers who conjure up Confederate zombies, Alt-Right disciples, and Barbie to bring about hell on earth. The apocalypse captivates the imagination, but it is not usually associated with Día de Los Muertos traditions, which center on ancestors, remembrance, impermanence, and the duality of existence.

Cordova’s visual narrative of the work of José Guadalupe Posada, the Mexican print artist, known for inventing the iconic dancing calaveras we know so well and are credited with seeding a populist art form used to mock the rich and powerful, is insightful and somewhat irreverent. Cordova argues (with other scholars) that the political nature of Posada’s art is overstated. Artisans such as Manuel Manilla and other anonymous printmakers who worked alongside Posada in Antonio Vanegas Arroyo’s print shop in Mexico City (1852-1917) contributed to the development of the calavera aesthetic. The sequence of prints curated from the era illustrates the evolution of the stylistic calavera with the enlarged head and teeth.

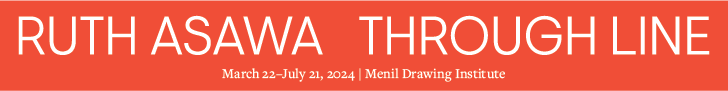

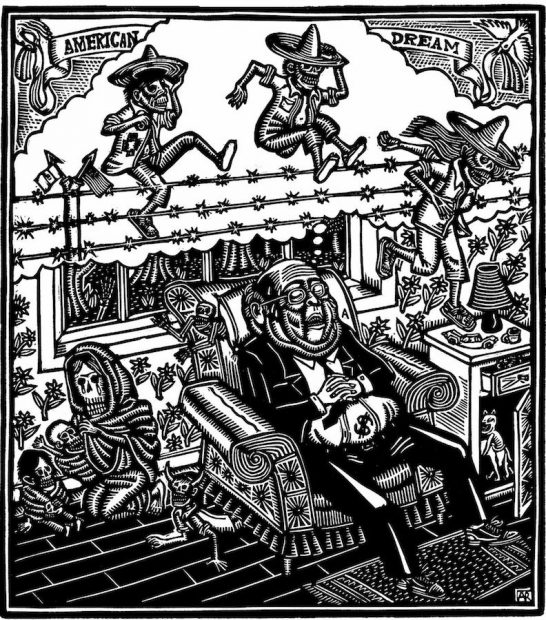

Posada’s photo-relief etching on salmon-colored paper of Francisco Madero, who ran against Porfirio Díaz in 1910, casts the revolutionary as a drunken peasant. Cordova’s reading of this particular image and others from the same period suggests that the skeletal caricatures that Posada and Manilla made were politically ambiguous. The dead stares back at the living in a soulful embrace of mutual recognition, which gives the artwork its psychological force and staying power. Artists who picked up the bones that Posada may have left unpicked have given the calavera genre a sharp political edge. Mexican artist Artemio Rodriguez is one of the most meticulous interpreters of Posada’s craft using carved woodcuts to create hand-printed black and white images. Somos Parte/We are Part (2006) is a scene from a defunct American dream. The central figure, a moribund capitalist, snores in a recliner chair in his business suit, clutching his money bags to his paunchy belly as he dreams of skeletal Mexican peasants jumping a barbed-wire fence. Chicano printmaker Juan R. Fuentes uses similar artistic techniques to comment on immigration. Se Vende (2013) depicts a skeletal pushcart vendor selling “eye scream,” witnessing an ICE agent detaining a young man wearing a Mexica headdress. In the United States of La Muerte (2004), Luis Valderas inscribes death and sacrifice into a ghostly flag with stripes that ripple with projectile skulls resembling a Mexica tzompantli, or stone skull rack carvings.

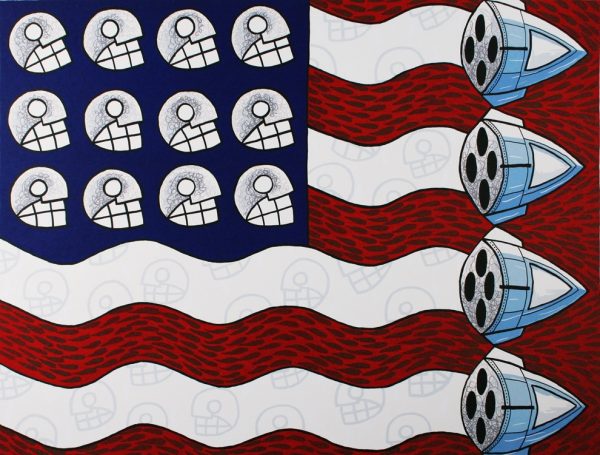

Most of the artists included in the show’s “Day of the Dead in the U.S.” section use skeletal figures and death imagery to critique modern statecraft such as immigration policy, settler colonialism, labor exploitation, capitalism, and racism. The revered Chicano Movement was at the vanguard of the calavera counternarrative. Ester Hernandez’s Sun Mad Raisins (1982), which replaces the wholesome sun maid with a calavera figure to make a statement about the deadly deceits of agribusiness, is transcendent. Two large paintings from Mel Casa’s Humanscape series comment on Southwestern clichés, and the commodification of Day of the Dead is especially prescient. Casas seems to project the future/present of the tradition that Enrique Martinez envisions in At the Altar (2006). Martinez, a graduate of UTSA’s MFA program, paints a syncretic Día de Los Muertos celebration. A mixed crowd — children and adults costumed as Mexican or U.S. pop-culture icons alongside skeletons and ghosts — gather around an altar/candy stand for treats or to venerate the Virgin of Guadalupe.

What makes the exhibit unique is that it moves beyond Day of the Dead as tradition to include artwork that explores death in Mexican folktales and the interplay between the sacred and the secular. Two paintings by Vincent Valdez, never before on view, recount the story of a young woman who encounters a handsome stranger at a dance who turns out to be the devil. El Diabo, at the Dance (2002), one of Valdez’s early works, is a full-length portrait of the devil with his ghastly chicken feet, posing in a bar in his signature black suit. Horrible snapshots of the women he has murdered surround him like traces of sin, blending folklore with a modern-day, seductive serial killer who stalks young women.

A more thrilling feminist retelling of this familiar folktale is long overdue. This version would have the young woman outwitting the diablo and booting him back to the underworld. Perhaps we can commission San Antonio native, Adriana Garcia, to paint a Chicana feminist rendition. Garcia contributed a small but charming painting of la mano podoroso, or, the hand of wonder. Blending the sacred and the secular, La Mano/The Hand (2009) is a religious meditation on immigration and how the mano is both a symbol of the deportable worker reduced to the laboring hand, and the faith that sustains a human being. The trace of a saint is embedded within each finger representing the Holy Family. Floating above the digits are elements of life and death — a skull, a plant, a hammer, and a hummingbird.

Luis Jiménez also explores religion and immigration enforcement in his poignant lithograph, El Buen Pastor/The Good Shepherd (1999). The work, like a prayer card, memorializes Ezequiel Hernández, a teenager from Redford, Texas, who was fatally shot by a U.S. Marine near his home in 1997 while tending his family’s goats. The young man is positioned within a blazing orange desert backdrop teeming with flowering cactus and yucca plants. He makes a saintly gesture of peace, with one hand raised and the other cradling a kid. But the “halo” that illuminates this secular saint’s head is not an adoration, but rather the telescopic lens of a rifle, with his face in the crosshairs.

In the section titled “The Mesoamerican Culture an Attitudes Towards Death,” Cordova leads the description with a provocative statement: “The amount of indigenous content in Day of the Dead is usually greatly overestimated.” He notes that indigenous belief systems are radically different from Catholic ones. Mesoamerican practices are so fragmented and obscured by the vicissitudes of conquest and colonization that it is impossible to suss what has become an amalgam of diverse influences. Yet, the historicity of Indigenous roots is beside the point. The artwork in this section is more invested in exploring Chicana/o/x Indignities and the legacies of colonial violence than questions of authenticity.

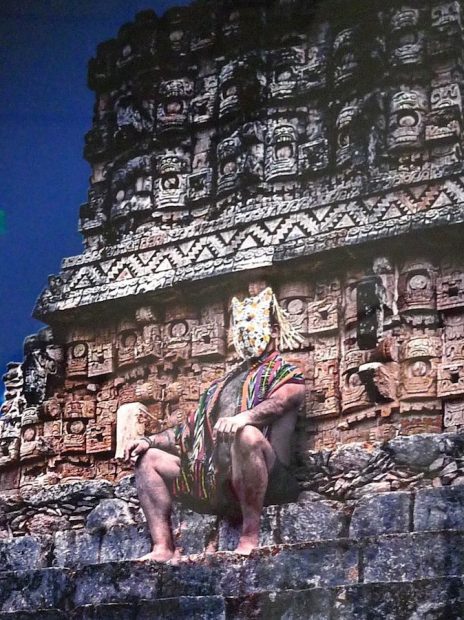

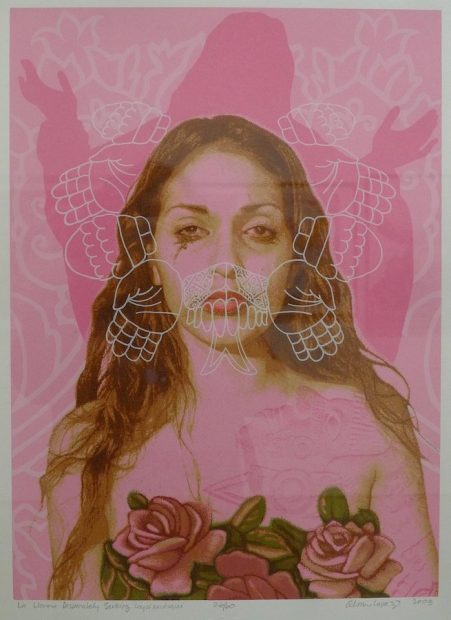

Kristel Orta-Puente’s photograph, Kan Xib Chacc Mask of Kabah: The Path to the Puente (2019), offers a moving glimpse into Chicana spiritual politics and reclamations of Indigeneity. Orta-Puente’s muse, Jacob David Lozano, who identifies as two-spirit, sits on the steps of the ancient Maya temple of Kabah at sunrise wearing a crocheted animal mask interwoven with pieces of obsidian, jade, turquoise, bone, and other objects. She describes her creative process as a spiritual journey centered on prayer and invoking the ancestors. Defilement of the sacred feminine is the theme of Alma López’s La Llorona Desperately Searching for Coyolxauhqui (2003). She describes the work as “a personal response to the rape, murder, and mutilation of women working in the post-NAFTA factories of Juárez, Mexico.” The photographic collage superimposes influential female figures, the La Llorona, La Virgin of Guadalupe, and also summons the Aztec goddesses, Coyolxauhqui and Coatlicue, to pay homage to the murdered women.

David Zamora Casa’s visually complex painting Until Death Do Us Part (1985) is the only piece that explicitly addresses LGTBQ themes. The central image is a bride and groom with divided half-skeletal faces framed by two pink doves that the artist describes as “homosexual couples in love.” The artwork represents themes of homophobia, the AIDS crisis, and the pretenses of heteronormative marriage. Many of the works in this wing make splendid use of Mesoamerican symbolism and iconography. However, Puerto Rican artist Martin C. Rodriguez’s installation, Righteous Indignation (2018-19), is an outlier. His gripping installation addresses the enslavement and decimation of the Taíno Indians, the aboriginal inhabitants of Puerto Rico. Twelve textured masks with horns shaped like plantains are pitched on metal stands resembling decapitated heads. The thick chain that hangs in the background refers to the transatlantic slave trade. In the spirit of the watchful masks, the artist recognizes the continuance of the Taíno people in the present.

Ruben Cordova’s heady themes and provocative collection of artworks invigorate El Centro de Artes, while showcasing the abundant talent and innovation of Mexican and Chicana/o/x artists, many of them who call Texas home.

Dr. Aimee Villarreal is an anthropologist and Assistant Professor of Comparative Mexican American Studies at Our Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio, Texas.

1 comment

Thanks for the review, Dr. Villarreal. I especially like this line: “Artistic responses to the apocalypse enclose the exhibition like a ring of fire.”