Editor’s Note: The following text by Ruben Cordova recounts his collaboration with the artist Roberto Gonzalez. Cordova is a scholar and active participant with the artists involved in the Chicano movement in San Antonio, and this story is part of a larger history that is not often retold or recounted. In this text, the author revisits his curation of an exhibition of works by Gonzalez.

Introduction

I revisit the exhibition Roberto Gonzalez: Sacred Waters from 2016 to explore an extraordinarily productive period of work by Roberto Gonzalez (b. 1955), a San Antonio-based Chicano artist. Gonzalez evolved from an abstract artist to a figural artist in order to explicitly explore indigenous subject matter. This article also serves as points of reference for two future Glasstire articles that I am currently researching. One will treat the Con Safo art group. Gonzalez made work that was almost unique within that group (Rosario Ezquerra was also an abstract artist), as well as very unusual for a Chicano artist in the 1970s. The other article will address the vogue for white walls that developed in museum and gallery exhibitions in the early and mid-twentieth century, and the fortunate return to a preference for colored walls in recent years. The exhibition Roberto Gonzalez: Sacred Waters serves as an example of my curatorial practice and of my preference for colored walls.

Roberto Gonzalez showing paintings at his home in Mico, Texas, August 12, 2015. “Hucun” (detail, not included in the “Sacred Waters” exhibition), 2010, acrylic on canvas, 90 x 78 inches. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

On a visit to the artist’s home and studio in Mico, Texas in 2015, I was astonished by the quality of his work, as well as the quantities he produced: he made 270 mostly large-scale paintings in 24 months, sometimes finishing seven (which he worked on simultaneously) in a week.

I saw hundreds of paintings in the artist’s large studio. He subsequently invited me into his living room to see even more paintings, which were stacked against walls like giant decks of cards (as in the above photograph).

In early 2016, I proposed the exhibition Roberto Gonzalez: Sacred Waters to Joseph M. Bravo, who was the director of arts at Centro de Artes (the former Museo Alameda, which was then operated by Texas A&M University, San Antonio). We wanted it to open in time for Contemporary Art Month in San Antonio, and when the exhibition was approved, we had one month’s time to put it together before the opening date. The main focus of this article is the Sacred Waters exhibition.

“Roberto Gonzalez: Sacred Waters” invitation card (2016), with image of “Kociyo,” 2014, acrylic on canvas, 80 x 64 inches. Card designed by Joseph M. Bravo.

About the Artist

Gonzalez was born in the border town of Laredo, Texas in 1955, to parents who emigrated from Coahuila, Mexico. After his parents separated, Roberto moved to San Antonio with his mother and brother when he was eleven. He returned to Laredo for high school, graduating from St. Joseph’s Academy in 1971. He returned to San Antonio and enrolled at San Antonio College (SAC). He studied with Mel Casas, who invited Gonzalez to join Con Safo, the San Antonio-based Chicano art group, during its last phase. Gonzalez entered the group by April of 1974. Gonzalez — unlike the other group artists, who were representational painters — worked as an abstract painter. He was also one of the earliest Chicano performance artists, commencing in 1974 (the artist was unaware of other Chicano performance artists until the 1990s). I first witnessed Gonzalez’s performances when he was a guest lecturer/performer in my art history classes at the University of Texas at San Antonio in the early 2000s. Gonzalez is a painter and graphic artist, a performance artist, and a musician.

Roberto Gonzalez performing “Escuchando a los Antepasados” (Listening to my Ancestors) at R Gallery, San Antonio 2012. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

In the 1970s, most Chicanos argued that Chicano art should serve the movement in a clear and explicit manner. Casas shielded Gonzalez from pressure (primarily from the Con Safo group’s last president, Rudy Treviño) to create representational, politically-oriented Chicano art. Gonzalez always believed that his work was inherently Chicano. He felt that his paintings’ colors and textures reflected his experiences as a child of the border and as a self-identified Chicano adult.

Gonzalez is one of the artists mischaracterized by Jacinto Quirarte as Mexican American rather than Chicano in his Tejanos catalog of 1990 (see the discussion in the appendix of my Adan Hernandez I article in Glasstire).

Gonzalez discusses why his abstract and performance work should be regarded as Chicano art in my book Con Safo: The Chicano Art Group and the Politics of South Texas (2009: 49). That book was researched in the early 2000s, when the artist was still an abstract painter. In late 1998 Gonzalez received a medical diagnosis that made him confront his mortality. He also served as the end-of-life primary caregiver for three successive family members between 1997 and 2002. These experiences led him to explore indigenous imagery and music in order to make contact with his ancestors. Gonzalez built a studio and house in Mico, and he began incorporating Mesoamerican motifs in his art in 2005.

Now, after having utilized figural imagery (though of a very non-traditional sort) for 17 years, Gonzalez notes that his earlier, fully abstract paintings were no less Chicano than his recent work, with its frequent allusions to pre-Hispanic cultures. He bristles at the thought that anyone else felt they had the right to categorize him in a manner that was antithetical to his self-identity.

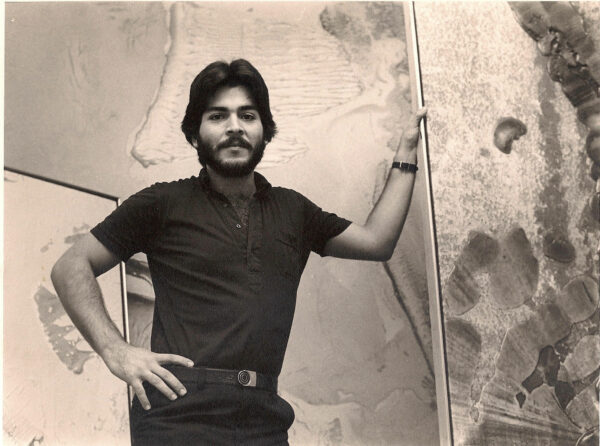

Roberto Gonzalez with three of his abstract acrylic paintings (including “Esid,” which is illustrated below), in preparation for his one-person exhibition at the Carver Cultural Center. Photo taken in his apartment near SAC, 1979. Photograph: courtesy of Roberto Gonzalez.

Gonzalez transferred to Trinity University in San Antonio and received his B.A. in painting in 1978. He went on to earn a B.B.A. from the University of the Incarnate Word in 1980. Gonzalez served as the Fine Arts Administrator at the Carver Cultural Center in San Antonio for eleven years (1984-1995), where he curated over 200 exhibitions and oversaw educational and cultural programs. The artists Gonzalez curated included Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett, Roy de Carava, Jacob Lawrence, Adrian Piper, and James Van Der Zee. Since that time, Gonzalez has pursued several other curatorial endeavors.

Roberto Gonzalez, “Esid,” 1979, acrylic on canvas, 88 x 67 inches, collection of the artist. Photograph: courtesy of Roberto Gonzalez.

Exhibitions and Artist Statements

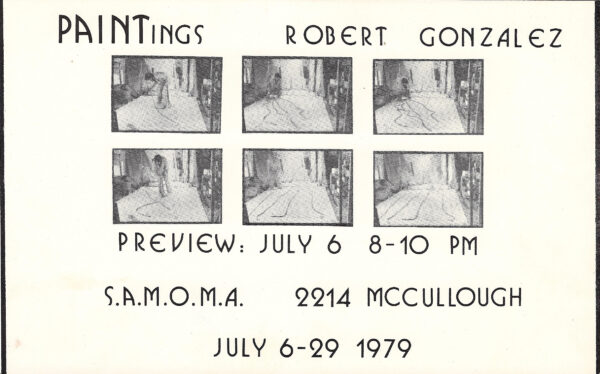

Roberto Gonzalez, invitation card for “Paintings,” a one person exhibition at the San Antonio Museum of Modern Art, 1979. Photograph: courtesy of Roberto Gonzalez.

In the above photograph, Gonzalez is applying “ropes” of dried acrylic paint (previously made by pouring paint in aluminum channels) to a large canvas. Gonzalez has always experimented with new ways of making paintings.

See Appendix B at the bottom of this article for a list of exhibitions in which Gonzalez participated.

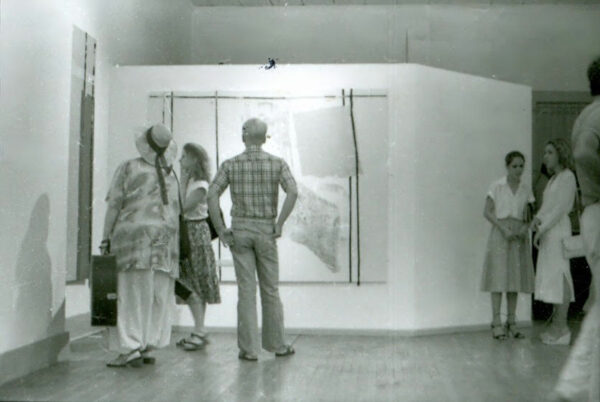

Roberto Gonzalez, installation shot of “Paintings,” a one person exhibition at the San Antonio Museum of Modern Art, 1979. Photograph: courtesy of Roberto Gonzalez. The paintings in this installation shot were made by gluing sheets and strips of dried acrylic paint onto stretched canvases.

Gonzalez currently has a diptych in Xicanx: Dreamers & Changemakers, an exhibition that opened in May at the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology, Vancouver, Canada.

From 1997 to 2005, Gonzalez largely withdrew from art-making due to the care-giving activities mentioned above. He did not exhibit his art for several years thereafter.

Gonzalez has been deeply interested in Carl J. Jung’s work since he was fourteen years old, when he read The Undiscovered Self (1958). His treatment of indigenous cultures is selective: he is not interested, for instance, in human sacrifice or warfare. Gonzalez’s engagement takes place through the filter of Jungian psychology, with an emphasis on self-healing.

The artist’s statements that he published in his early catalogs are rather cryptic, without a background in Jung, so I have asked Gonzalez to elaborate on a couple of sentences (a selection of the artist’s statements are reproduced in Appendix A at the bottom of this article). In the ¡Mira! The Canadian Club Hispanic Art Tour catalog (1984), for a show that traveled to New York, San Antonio, and Los Angeles, Gonzalez declared: “Painting is my spiritual drowning.” He explained to me that painting requires “the death of the ego,” of the “self-as-ego.” This “death” then “allows the slipstream of the unconscious to open up.” In the ¡Mira! catalog, he also stated: “The reality of the painted surface opens my eyes in living prayer.” This sentence expresses the artist’s belief that when he is painting, he is “living in a moment of creation” in which the “mysterium magnum” — by which he means the universe/nature/god — “is flowing through me.”

In a review of the ¡Mira! exhibition, Suzanne Muchnic wrote: “The exhibition’s emotional tone plunges from this fevered pitch to the comparatively chilly remove of Juan Mele’s and Robert Gonzalez’s abstractions that allude (mostly through artist’s statements) to mysteries of human existence and concern with urban space” (“Latino Artists examine issues in ‘Mira!,’” Los Angeles Times, November 19, 1984.)

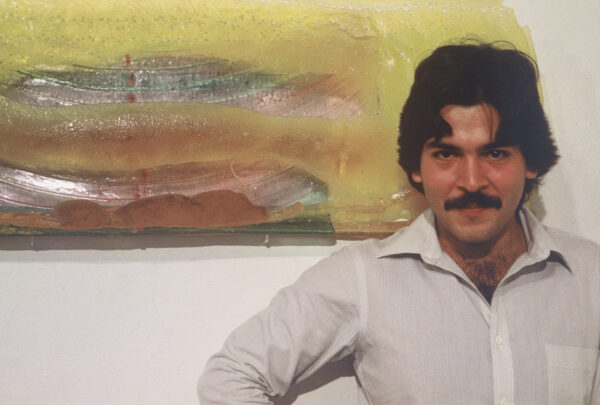

Roberto Gonzalez with untitled polyester resin painting, Shown-Davenport Gallery, San Antonio, 1982. Photograph: courtesy of Roberto Gonzalez.

Gonzalez always made experimental paintings. In this series, he made self-supporting paintings (without canvas or wood supports, a stretcher, or a frame) out of resin. This is the only painting in this series that is relatively flat. The others have elements that project from the walls. He explained to me that he wanted “to challenge the assumption that paint on a painting is always flat and parallel to the wall.” Gonzalez would subsequently use the decal process in which he painted on plastic, and transferred the wet paint to canvas. He used the decal process for most of the paintings in “Sacred Waters.”

In the Tejanos catalog (1990), for an exhibition that traveled to the Museo Carrillo Gil in Mexico City, Gonzalez cloaks his art in an aura of mystery: “I work in a circle which is not round. …The challenge is to signify without using signs knowable or unknowable; those signs which fall between the thought and the vision is what I pursue.” During this period, Gonzalez wanted to avoid forms that could be regarded as conventional signs or symbols.

Gonzalez’s 2018 piece Una Limpia de Colón: Eres un Conquistador (A Columbus/colon Cleansing: You are a Conquistador), on the other hand, utilizes three primary symbols: Columbus, Quetzalcoatl, and the Alamo. I commissioned it as one of the centerpieces of my exhibition The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth (San Antonio: Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, 2018). Morgan O’Hanlon illustrated it in the Texas Observer and noted: “Quetzalcoatl’s passage through the Alamo’s front door likens the rejection of Christopher Columbus’ heroic place in history to a colon cleansing — a play on the double meaning of the colonizer’s name.” For Gonzalez, Jungian healing serves as a remedy for the trans-generational trauma caused by European colonization. He offers this advice in the catalog: “cultivating connections to self and community, strengthening ritual practice, and resonating with the wisdom of the ancestors. Sing, and their breath will find you.”

Gonzalez’s diptych in the Vancouver Xicanx exhibition, which features skeletal figures in stark black-and-white, is titled El Paso 8/3/19, No Hate, No Fear (2019). It addresses the massacre at an El Paso Walmart, as well as the shock and grief it engendered. The mass-shooter traveled to El Paso specifically to hunt Mexicans. The two canvases were among the seven I commissioned from Gonzalez for the exhibition The Day of the Dead in Art at Centro de Artes in 2018-19. (Click here for a PDF of the catalog.)

The diptych resonated with the public, and many writers discussed it in reviews of the Vancouver exhibition. Spanish language publications include: Chronica, La Jornada, El Universal, ASICH, and Hoja de Ruta. English language publications include: Broadway World, Stir, The Georgia Straight, The Peak, 6 Park News, Galleries West, Side Real 7, West Coast Curated, and Darik News Arizona.

The Columbus picture and the diptych are the most politically explicit paintings that Gonzalez has made to date. They represent quite a departure form his abstract work.

Pre-Hispanic and African Diaspora Music and Performances

Gonzalez has studied with numerous masters who played the music of the African Diaspora, including in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil. As a percussionist, he took classes with the Nigerian master drummer Babatunde Olatunji, with the Puerto Rican conguero Patato Valdez, and with the Jazz drummer Max Roach, who was also interested in the music of the African diaspora. Gonzalez has performed this music with numerous groups, including Ile Bahia de San Antonio and Laza. Gonzalez also composes and plays music with pre-Hispanic instruments, and he has released several CDs of this material under the name Xivero. He is currently co-Artistic Director of Son Olvidados, a street performance group that plays percussion-based music. I have photographed the group several times during Day of the Dead processions in San Antonio, at Market Square and La Villita. Gonzalez has also performed music extensively in Texas, Arizona, and Mexico. He additionally performed at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., with Urban-15 in 1997.

Son Olvidados (in background) performing in Market Square with two of the Day of the Dead puppets from the group Las Monas, San Antonio, 2011. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova. The two groups have been performing together for more than twenty years.

Carl Jung, Dream Images, Pre-Columbian Iconography, and Psychic Healing

Gonzalez worked as an abstract artist from 1972 until 2005, when he began to use representational forms. The artist’s Jungian beliefs presented unique challenges when I put together the Sacred Waters exhibition: the artist and I had to quickly select, categorize, interpret, and decide how to present a complex body of work.

When he created these works, the artist had deliberately avoided rational thought practices as much as possible. As I noted in a Sacred Waters wall text:

Gonzalez envisions forms and colors. They give rise to strong emotions and the compulsion to paint. He paints the shapes and colors that he has already seen. He does not work with language-based concepts or intellectual programs of any kind. Prior to the preparations for this exhibition, Gonzalez had not tried to put his paintings into categories, or discern their meaning. Nor had he given any of the paintings titles.

“These images are gifts,” says the artist. “I open myself to them in gratitude and share them with mystery.”

(The passages in italics in this article are taken from my exhibition wall texts.)

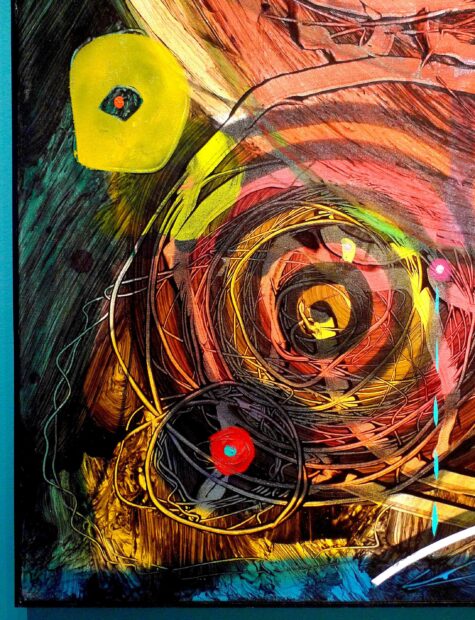

Roberto Gonzalez, detail of “Rau,” 2010, acrylic on canvas, 90 x 78 inches, in the “Sacred Waters” exhibition. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The “goggle eyes” in the above detail (as well as the streams of water) reference the pre-Hispanic rain deities known as Chac to the Maya, Cocijo to the Zapotecs, and Tlaloc to the Aztecs. One can see varied painterly effects and textures in this painting.

The reddish orbs within the green forms in the painting “Hucun” in the artist’s home (reproduced above) likewise evoke the rain deity’s eyes. The large kaleidoscopic forms in the bottom of that picture reference earrings. The creature in the painting Kociyo (reproduced on the invitation card above) is also a rain deity.

Gonzalez’s practices are rooted in Jungian beliefs. He believes the deepest and most profound imagery can best be accessed through the archetypes housed in the unconscious:

Jung argued that a universal collective unconscious filled with primordial images called archetypes constituted the common heritage of the entire human race, regardless of historical epoch, cultural influences, or geographic circumstances. While Jung held that the conscious mind of every person was uniquely individual, he believed that the unconscious was a storehouse of forms that found expression in myths and symbols that manifested themselves repeatedly throughout human existence. These ideas have had a substantial impact on popular culture. One example is the influence they had on Joseph Campbell’s writings on myth, which George Lucas consulted when he was working on the scripts for his Star Wars films.

Gonzalez believes access to the unconscious provides the key to healing trans-generational trauma, such as that caused by the conquest of the Americas by Europeans, which resulted in genocidal practices and the devastation of indigenous cultures:

As someone who is deeply immersed in Jungian psychology, Gonzalez believes that trauma and pain can be transferred across generations from parent to child. He identifies with the pre-Columbian cultures of Mexico, and feels the pain of the loss and destruction of their cultures “beyond measure.” His dreams, meditations, and art are therapeutic practices intended to heal these ancient wounds.

Gonzalez believes that accessing the Jungian unconscious provides the key to mental health as well as the gateway to his ancestors:

Jung held that the collective unconscious exerts an enormous influence on all of humanity: resisting and repressing the unconscious causes neurosis and dissociation; creatively exploring and embracing the unconscious, on the other hand, leads to healing and completeness. Jung himself made art, and he believed that art could be an important therapeutic tool.*

Through his explorations of the Jungian unconscious, Gonzalez makes psychic journeys that bring him into contact with his indigenous ancestors, enabling him to see through their eyes and experience their worlds. “I believe it is through my paintings that I begin to heal,” declares the artist.

For the purposes of his art, the early morning is the most vital time for Gonzalez. The most critical juncture is when he is coming out of a dream state, “standing between consciousness and unconsciousness.” Gonzalez has developed what he calls a “creative collaborative relationship with the unconscious.” Through “lucid dreaming” and deep meditation, Gonzalez believes that he can “psychically go back in time” by harnessing the “jet-stream where the ancestors are waiting,” and where they are able to provide him with positive creative connections and sources of inspiration.

Roberto Gonzalez, detail of “Xauc,” 2010, acrylic on canvas, 90 x 78 inches, in the “Sacred Waters” exhibition. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Gonzalez utilizes a multiplicity of circular forms and techniques to suggest eyes and the flow of water. In the painting illustrated above, it is a tear-like stream. From a distance, the primary color of this painting is brown, but upon close looking, one can make out many colors, as well as graffiti-like circles and scribbles where Gonzalez scratched away the paint on the plastic before it was transferred to the canvas.

In order to better familiarize himself with pre-Hispanic artifacts and imagery, Gonzalez visited archaeological sites and he studied museum collections, books, and images of Tlaloc, Cocijo, Chac and other Mexican rain gods that he accessed through ARTstor. He deploys these pictorial elements in a “spirit of mixture” by creatively combining particular details and devices without seeking archaeological completeness or specificity.

*Jung, C. G., Sonu Shamdasani, Mark Kyburz, John Peck, and Ulrich Hoerni. 2009. The red book = Liber novus. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. For an introduction to Jungian psychology with special reference to art, see: Jung, C. G., and Marie-Luise von Franz. 1964. Man and his symbols. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday.

The Exhibition is Approved and We all Spring into Action

I returned to the artist’s house and studio in Mico with Bravo, who was equally amazed by his work and who very badly wanted to mount an exhibition of the work at Centro de Artes. I asked Gonzalez to make the following preparations: to divide the paintings he had shown us into categories; to determine the theme or defining characteristics of each category; to select what he thought were the best examples of each category; and to measure and name or number each individual painting.

Gonzalez visited me in San Antonio and we studied color reproductions of each work, which I ranked within each category. One category of paintings clearly referenced Pre-Hispanic water deities (with goggle eyes, fangs, and water) and we called this group Sacred Waters. Another group of paintings depicted structures, which the artist named Temazcal (sweat lodge). Another had contrasting characteristics, which he called Duality. Before I had seen them, Gonzalez had already referred to a group of black-and-white paintings as Dreamstacks. Finally, there was a group of miscellaneous works that we called Preludes.

The exhibition was approved and we all sprang into action. In consultation with the artist, I chose wall colors for each group, and began writing wall texts. The artist and I laid out the exhibition together. Gonzalez framed and wrapped his paintings. A total of 44 were ultimately included in the exhibition, including Ollin, (illustrated at the beginning of the article), which was painted for the lobby. For maximum impact in this huge space, I wanted the painting to be as big as possible. It was: we ultimately had to loosen the hinges of the doors in order to slide it into the building.

Bravo prepared and painted the walls, and designed a banner, brochure, and other materials for the exhibition. The paintings were unpacked and placed in their proper locations. Bravo directed the hanging and lighting of the works. My wall texts were completed and mounted just before the opening.

Wall Color Symbolism

Installation shot of “Sacred Waters,” first gallery, with Roberto Gonzalez giving a tour to a friend. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The following is a passage from my introductory wall text:

These paintings constitute an aesthetic and psychological exploration of ancient Mexican myth and religion. In the artist’s view, water is an agent of transformation, as well as the source of life. In Gonzalez’s work, water is transfigured by reference to ancient myth and image. Water resonates from ancient symbolic images across the millennia to take on new forms in this time and place.

I wanted the wall colors to have a deep symbolic resonance with each group of paintings. The entrance was left white. The color selected for the first gallery was a dramatic turquoise (Sherwin Williams’ “Pursuit of Teal”). I wanted the effect of plunging into a cenote (a sacred Maya sinkhole), whereby everything would be colored by the enveloping turquoise walls, as if one were looking at the paintings underwater.

Gonzalez notes that the paintings looked different in the turquoise galleries than they did in his home or studio, which have white walls. He said he felt “immersed in and embraced by Tlaloc’s watery realm.” Gonzalez added: “it was a profound perceptual experience to be surrounded by kindred groupings of paintings. Experiencing the paintings in this manner enabled me to understand my own body of work in a deeper manner.” Gonzalez had been so prolific in the previous five years that he hadn’t taken the time to really assess what his paintings meant.

Installation shot of “Sacred Waters,” with freestanding turquoise walls. The photo was taken from the first gallery, facing the gold wall with the Dreamstack paintings. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Initially, I didn’t like the short, freestanding walls that led out of the first gallery. But then I realized that I could utilize them in a conceptual manner. I could color them turquoise, and thus continue the flow of life-giving liquid, symbolically “watering” the other components of the exhibition: the Dreamstack series on the distant gold wall; the Temazcal (Sweat Lodge) series that extended along the earthen-colored walls on the left; and the Duality series that extended along the red walls on the opposite side. The Preludes are located in the lobby and on white walls in the distant far corners.

Installation shot of “Sacred Waters,” with freestanding turquoise walls, from near the far corner of the red Duality wall. Roberto Gonzalez is near one of the freestanding turquoise walls. In the center, one can glimpse a section of the first gallery. The earth-colored Temazcal walls are visible on the right. The reflections on the floor and ceiling give a sense of how the colored walls color the spaces of the exhibition. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Installation shot of “Sacred Waters,” with freestanding turquoise walls, from near the far corner of the earth-colored Temazcal walls. The red Duality walls are visible on the left. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Sacred Waters

The following paragraphs are from the text panel in the first gallery.

Water is life. Ancient Mexican cultures revered jade and Quetzal feathers above gold and all other substances because their shimmering blue-green surfaces were the color of water, the color of life itself. Pilgrimages were made to sacred bodies of water, where jade and gold objects were thrown into the waters as offerings.

Water was either too scarce or too perilously overabundant in most of ancient Mesoamerica. In the Gulf Coast region of Mexico, home to the Olmec, the mother culture of Mesoamerica, the water gods protected against devastating storms and deadly floods. In more arid regions, they brought life-sustaining rain.

Prolonged drought led to the Classic Maya Collapse, resulting in the abandonment of many of the great Maya city-states by 900 A.D. As a resident of the Texas hill country in Mico since 2002, Roberto Gonzalez became all-too-familiar with the effects of drought. His well dried out and he prayed for rain. He subsequently celebrated every rainfall and came to “measure my life according to the rains.”

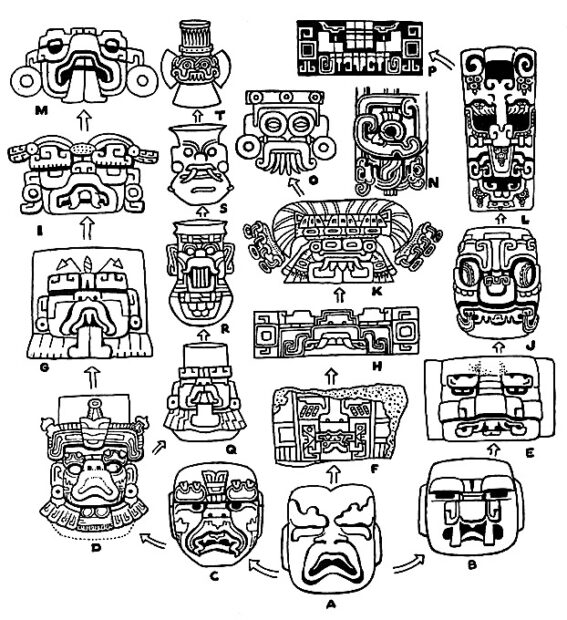

Miguel Covarrubias, Chart of Mesoamerican Rain Deities, originally published in “Indian Art of Mexico and Central America” (Knopf, 1957: 60).

Covarrubias’ famous chart depicts the evolution of rain deities, from an Olmec human-jaguar composite mask (see discussion of the “were-jaguar” below) labeled A in the lower center. The rain god (labeled C) gave rise to the Oaxacan rain gods in the left column (including the Zapotec Cocijo that Gonzalez frequently references). Figure D also evolved into the central Mexican rain deity (Q, R, S, T) that the Aztecs called Tlaloc. Figure A leads to the Gulf Coast rain deities directly above it, as well as to the Teotihuacan rain deity, in the manner that it appears in wall paintings (K). Gonzalez makes extensive use of the circular elements seen in the Mixtec (O) type. In the column on the right, Covarrubias traces the development of the Maya rain deity Chac, which is shown as it appears in ceramic censors, like those from Palenque (L), as well as its architectural form, when it serves as a temple façade (P). Gonzalez utilizes square eyes and ear ornaments that have much in common with the latter.

Each of the paintings in the Sacred Waters section contains pictorial elements taken from one or more Mexican water god. One of Gonzalez’s chief sources of inspiration for this theme was a chart by Miguel Covarrubias, who wrote important books on the indigenous peoples of the Americas. Covarrubias’ ingenious chart showed how the water gods in other major Mesoamerican cultures evolved from Olmec examples, including the Maya god Chac, the Teotihuacan rain god (name unknown), the Zapotec god Cocijo, and the Toltec and Aztec god Tlaloc.* Covarrubias, a self-taught artist with no college training in any field, corrected the many scholars who believed that the Classic Maya (300 – 900 AD) were the originators of Mesoamerican culture. Mesoamerican culture is now viewed as a continuum that stretches back to 1500 BC or even earlier, when Olmec culture began.

Installation shot of “Sacred Waters,” with Roberto Gonzalez in conversation with a friend. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The elements Gonzalez takes from these water gods include fangs (which have their origin in Olmec jaguar imagery), large and round “goggle” eyes from Chac and Tlaloc (that perhaps evolved out of cloud-shaped Olmec eyebrows), a cleft forehead (which, in some Olmec examples, had corn sprouting on both sides of the cleft), and a stylized, toothless open mouth, which also originated with the Olmec. Gonzalez often includes stylized representations of water falling from open mouths or water vessels, and pools of water bubbling up from the earth. In all of these images the artist endeavors to “celebrate the color and energy of nature.”

Gonzalez employs his precious rainwater in his art: “I use rainwater to dilute my acrylics. It flows and extends colored pigment across a taut surface. Water flows through my veins and across my brow. As an artist I look to my ancestors, especially the artists who lived and painted thousands of years ago. I am compelled to visit them and learn. I don’t learn their technique and processes, but rather their fierceness of spirit: what it means to be birthed from waters, to live, to create, and to become dust and return to the earth.”

The Sacred Waters series continues on both sides of the two blue walls in the center of the next gallery, which serve as a symbolic river that gives life to the other series.

*Covarrubias, Miguel. 1957. Indian Art of Mexico and Central America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, p. 60. For a discussion of Covarrubias’ chart (including recent theories that revise his interpretation), see Markman, Peter T., and Roberta H. Markman. 1989. Masks of the spirit: image and metaphor in Mesoamerica. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 9-11. For a guide to Mesoamerican gods and imagery, see: Miller, Mary Ellen, and Karl A. Taube. 1993. The gods and symbols of ancient Mexico and the Maya: an illustrated dictionary of Mesoamerican religion. New York: Thames and Hudson.

Duality

Installation shot of the first part of the Duality section of the “Sacred Waters” exhibition. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

After choosing the fieriest red paint that I could find for the Duality walls (Sherwin Williams’ “Show Stopper”), I began the Duality wall text with the following passage:

Duality, the belief that pairs of opposing forces are in conflict, is a key concept in both Mesoamerican religion and Jungian psychology. The Duality walls are red. Red stands for fire, a transformative, unstable, consuming agent associated with many opposites, such as creation and destruction, good and evil.

I cited my favorite book on fire, Gaston Bachelard’s The Psychoanalysis of Fire. Here, I offer a key passage from that book that explains why red is the appropriate color for this section:

“Fire is thus a privileged phenomenon which can explain anything. … It is intimate and it is universal. It lives in our heart. It lives in the sky. … Among all phenomena, it is really the only one to which there can be so definitely attributed the opposing values of good and evil. It shines in Paradise. It burns in Hell. It is gentleness and torture. It is cookery and it is apocalypse. … It is a tutelary and a terrible divinity, both good and bad. It can contradict itself; thus it is one of the principles of universal explanation” (originally published in 1938; English translation, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1964, p. 71).

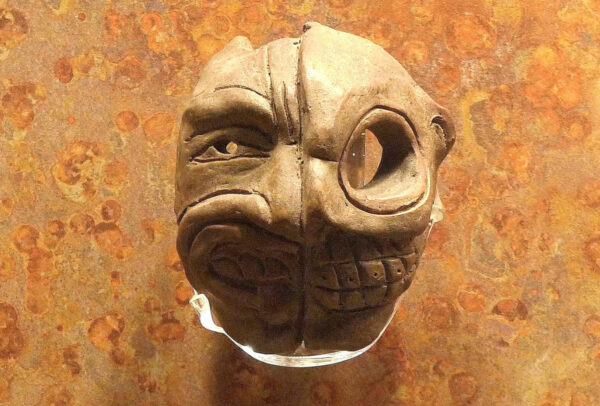

“Life/Death mask,” ceramic, Tlatilco culture, c. 1200-600 BC, Valley of Mexico, Anthropology Museum, Mexico City. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova. For more images, see Smarthistory video and photos here

A number of striking Mesoamerican masks and figures feature a dualistic face that is half skull and half living flesh. One of the most striking examples is a small mask from Tlatilco in the Valley of Mexico.

Professor James Maffie points out that for Mesoamericans,

“Life and death are mutually arising, interdependent, complementary, and competing aspects of one and the same process. They are inextricably bound to one another since neither can exist without the other. Life without death is impossible, just as is death without life. Life contains the seed of death; death, the fertile, energizing seed of life. Life feeds off the death of other things, and so has a negative aspect. Death feeds life, and so has a positive aspect. In short, life and death are ambiguous: both positive and negative.”*

Maffie points out that the Tlatilco life / death mask is intentionally ambiguous: “Skulls simultaneously symbolize death and life, since life springs from the bones of the dead. Flesh simultaneously symbolizes life and death, since death arises from living flesh.”* For Mesoamericans, bones were powerful reservoirs of vital life forces. The Aztecs believed that the god Quetzalcoatl reanimated the human race by sprinkling his blood on human bones that he stole from the underworld. Maffie adds that these dualistic masks are “neither-alive-nor-dead yet at the same time both-alive-and-dead.” Moreover, all of existence was conceived of as an eternal “back-and-forth struggle” between opposed forces that resulted in the “alternating dominance” of one conflicting element over the other. Consequently, existence was conceived of as an unstable, perpetual struggle that was itself “irreducibly ambiguous (like the life/death masks).”*

Jung also viewed life as a struggle of opposing pairs:

“… life consists of a complex of inexorable opposites—day and night, birth and death, happiness and misery, good and evil. We are not even sure that one will prevail against the other, that good will overcome evil, or joy defeat pain. Life is a battleground. It has always been, and always will be; and if it were not so, existence would come to an end.”**

The observations Maffie makes about life and death, that they “are mutually arising, interdependent, complementary, and competing aspects of one and the same process” apply equally well to Jung’s formulation of the dynamic between the conscious and the unconscious.

Roberto Gonzalez explaining his concept of dualism at the opening of “Sacred Waters” (with Lance Aaron and Kristel Andrea Orta-Puente on the left side of the picture). The two paintings behind him are half-skull- and half-butterfly and half-scorpion. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Gonzalez’s first painting in the Duality series was a depiction of a half-skull and half-living human face. The paintings evolved into an energetic set of abstracted fantasy creatures: half-skull and half-butterfly, half-skull and half-scorpion, half- rattlesnake and half fanged-abstraction. The artist had many fatal encounters with Texas rattlers on his homestead and he was compelled to consecrate them in his paintings.

Gonzalez is also influenced by other manifestations of duality in folk art, such as modern folk masks, and the fantastical creatures made by the Linares family in Mexico City that are known as Alebrijes (dragons). Whatever his inspiration, Gonzalez always transforms his source material into his own personal artistic language. One of the aims of this body of work is to view transformation and the cycle of life with a celebratory embrace rather than with fear. Gonzalez recognizes this dynamic in Day of the Dead, and he is an active participant in these commemorations in San Antonio.

* James Maffie. 2011. “Weaving the Aztec Cosmos: The Metaphysics of the 5th Era,” in Aztecs at Mexicolore.

**Carl Jung, Man and his symbols, p. 85.

Temazcal (Sweat Lodge)

Installation shot of the first part of the Temazcal section of the “Sacred Waters” exhibition. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova

The Temazcal (Sweat Lodge) series references ancient healing traditions. The Temazcal walls are brown [Sherwin Williams’ “Harvest Gathering”] to symbolize a brown body covered with steam and sweat, and the earth bathed with rain and dew.

In the Temazcal ritual — as Gonzalez describes it — all of the elements are ceremonial: the offering of flowers and food; the building of the fire; the placement of the rocks in the fire; the movement of the rocks into the center of the Temazcal; the pouring of the water over the hot rocks (which creates the steam bath). Gonzalez views the transformation of water from a liquid state to a gas vapor as a metaphor for the transformation of self.

In Nahuatl (the language of the Aztecs) Temazcal means bath (temas) house (calli). The sweat lodge is among the most widespread of the traditional indigenous medicinal practices of the Americas. In Mesoamerica, it was not utilized primarily as a relaxing sauna (as in Scandinavia and much of the world). Nor did it mostly serve ceremonial uses, as was the practice in much of North America. Instead, as Horacio Riojas Alba observes, the Temazcal was “used in the healing and easing of almost all kinds of medical conditions.”* The sixteenth century Franciscan friar Diego Sahagún noted: “It is used firstly in the convalescence of many sicknesses, so that they should finish healing more rapidly…. All sick people benefit from these baths….”* It was thought to heal a wide range of traumas and afflictions, including contusions, broken bones, skin ailments and growths. According to Sahagún, the Temazcal also aided “pregnant women who are close to giving birth as there the midwives can do certain things so that the birth is easier.” It healed mothers after they gave birth, and it was even credited with purifying their milk.*

“Magliabechi Codex,” depiction of Temazcalli, from 1903 University of California publication. Photo: Ephert / Wikimedia Commons.

The Magliabechi Codex, an illustrated manuscript that dates from shortly after the Spanish Conquest of 1521, features an indigenous drawing with a Spanish caption that reads: “This is a drawing of the baths of these Indians which they call the temazcalli. At the door of the bath there is an Indian who is the advocate for the sick, and when a sick person goes to the baths he makes an offering and stretches his body on the ground in veneration of the idol which they call Tezcatopocatl and who is one of their principal gods.”* Medicinal herbs were utilized in the steam.

Riojas Alba points out that the Temazcal’s structure follows the cosmic directions: “the fire which heats its stones is placed towards the east where our Father, the sun, the god called Tonatiuh, arises; he is the light or masculine element which comes and fertilizes the womb of the mother earth (the chamber of the Temazcal itself), and so life is conceived. The doorway through which the bathers enter and leave is oriented toward the south, ‘the pathway of the dead,’ which begins with birth and ends in death, to the right of the path of Sun. In this way, the ever-present duality of traditional Mexican thought is manifested. Just as there are mother and father, sun and earth, hot and cold, so we are born and, in being born, we begin our path towards death.”*

As Riojas Alba notes, the Temazcal represents the womb: “we enter a small, dark, warm and humid space, in this way recreating the uterus…. Our re-emergence through this narrow opening represents our rebirth from the darkness and silence of the womb.”*

Roberto Gonzalez’s father taught him healing sweating techniques when he was a child. In Gonzalez’s paintings the Temazcal serves as a metaphor for self-healing, particularly the trans-historical psychic pain that stems from the destruction of indigenous civilizations in the aftermath of the Spanish Conquest.

For Gonzalez, the Temazcal provides a communion with the ancients. It is also a mechanism for “coming home” to the integrated self. Thus it also provides a connection to the self and to family and to the local community in the present.

The Temazcal series represents a metaphorical rebirth, an affirmation of physical health, and a reminder of our connection to the earth. In Jungian terms, it is a return to the Great Mother.

The paintings as a group feature an aesthetic reduction to minimal features. Black is a sign pointing to the doorway of the darkness of the unconscious.

* Horacio Riojas Alba. 2006. “Temazcal: the Traditional Mexican Sweat Bath,” Tlahui-Medic 2.

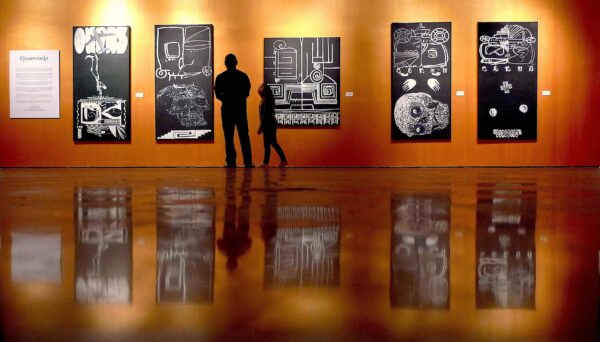

Dreamstacks

Roberto Gonzalez, installation view of the Dreamstack series on the gold wall, and their reflections on the floor. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Gold is used as the background color for the Dreamstacks to symbolize the purity and incorruptibility of the unconscious and the high valuation that the artist places upon it. For Jung, who compared alchemy to psychology, gold also symbolizes the perfected soul.

(See: “Carl Jung Biography” and Jung, C. G. 1968. Psychology and Alchemy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.)

I selected Valspar “Gold Leaf” paint for this section because it was the truest gold I could find.

The Dreamstacks are the most immediate and direct paintings Gonzalez has ever done. He uses no preliminary drawings. The paint is applied spontaneously, with no prior sketching or conscious planning of any kind. The series began as images that appeared in dreams. Gonzalez recalls: the term Dreamstack “came to me midway through a lucid dream as a calling to stack the images that were given to me by my unconscious.”

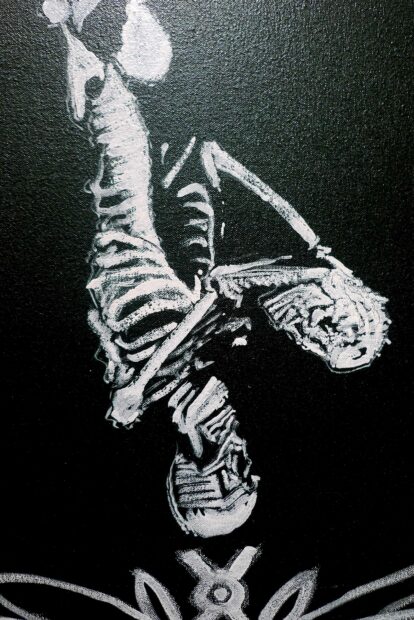

Roberto Gonzalez,“Sueño” (detail of upside-down skeleton looking at skull), oil on canvas, 80 x 40 inches, mixed media on canvas. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

This group of paintings is almost purely tonal, nearly all black and white. Several types of white paint (oil, oil stick, spray can paint, acrylic) are applied to black and dark green painted grounds. Dark green is here understood as a life color in opposition to black, which is often interpreted as a death color. Gonzalez believes that the unconscious is more like a black-and-white painting than a painting with many colors. He associates black with the unconscious because “it can never be fully known.” Since they are simpler transcriptions of dream images than paintings with color, Gonzalez places a special value on this series because it had less need for input from his conscious mind.

Roberto Gonzalez, installation shot with Roberto Gonzalez, Jesse Borrego, and three Dreamstack paintings (“Kallo,” 2015, oil on canvas, 80 x 40 inches; “Azal,” 2015, oil on canvas, 60 x 52 inches; “CABRN,” 2015, 80 x 40 inches).

The Dreamstacks have faces that are split down the middle. One side is clear and the other side is blurry. Perhaps these paintings are visual interpretations of the Jungian concept of “individuation,” wherein the conscious and the unconscious are brought into consciousness together. Jung believed this process was necessary for the integration of the psyche and good mental health:

“For the sake of mental stability and even physiological health, the unconscious and the conscious must be integrally connected and thus move on parallel lines. If they are split apart or ‘dissociated,’ psychological disturbance follows…. dream symbols are the essential message carriers from the instinctive to the rational parts of the human mind, and their interpretation enriches the poverty of consciousness so that it learns to understand again the forgotten language of the instincts.”*

Jung argues that consciousness is weak and vulnerable. Moreover, over-emphasis on rationality is dangerous: “Consciousness is a very recent acquisition of nature…. It is frail, menaced by specific dangers, and easily injured.”* Jung believes that dreams serve a vital role, since their general function is to “try to restore our psychological balance by producing dream material that re-establishes, in a subtle way, the total psychic equilibrium.”*

* Jung, C. G. Man and his symbols, p. 52, 24, 50.

Preludes

Roberto Gonzalez, installation shot with three Prelude paintings (from left to right): “Xip,” 2015, 60 x 52 inches, acrylic on canvas; “Tequieroamor,” 2015, 60 x 52 inches, acrylic on canvas; “Tenoch,” 2015, 60 x 52 inches, acrylic on canvas. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Having already chosen wall colors that stand for water, fire, and earth, I wanted to account for the fourth element, so I used white to stand for air / ether, even though all of the Prelude paintings would look better on colored walls.

My preference for brightly colored walls stems from my first experiences as a curator at the Mexican Museum in San Francisco in the early 1990s. I have always felt that white walls suck the life out of great paintings. Any strong painting looks better on an appropriately colored wall — though weak paintings can be overpowered by colored walls.

I described the Preludes in my wall text as “primarily non-related, singular works… a product of riffing and improvisation” that were made shortly after Gonzalez awoke from a dream state. Many were painted before the various series we have already looked at in this article. Gonzalez characterizes the Preludes as exercises in “priming the pump.”

Xip is an improvisation based on a pre-Hispanic water vessel with a turtle shell pattern that the artist saw online about a decade ago. The artist liked the “near-abstract expression of the back of the turtle shell,” which he “deconstructed and translated into a two-dimensional form.”

The artist refers to “Tequieroamor” as “an expression of pain and suffering,” which he associates with love. The vase represents a fallen body overflowing with love (flowers). A letter on each bleeding, heart-shaped flower spells out the title of the painting, whose possible meanings I discussed in the wall text: “The title (I love you love) is ambiguously redundant: it could mean wanting love, wanting my love, wanting to be loved, or simply loving love.”

Teotihuacan culture, Mexico, Singing Priest or God, c. 400-600 A.D., fresco, 23 11/16 x 43 ½ inches, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

Tenoch features three triangular-shaped maguey fronds that are buried in the earth with their pointy sides down. Their spiny points were used for ritual blood-letting in Mesoamerican cultures. This motif was inspired by details in wall frescoes from Teotihuacan. In the example illustrated above, five maguey spines rest in a bed of reeds in the lower left corner. The two red circles in Tenoch reference circles in Teotihuacan architecture. Gonzalez added other design features to the painting.

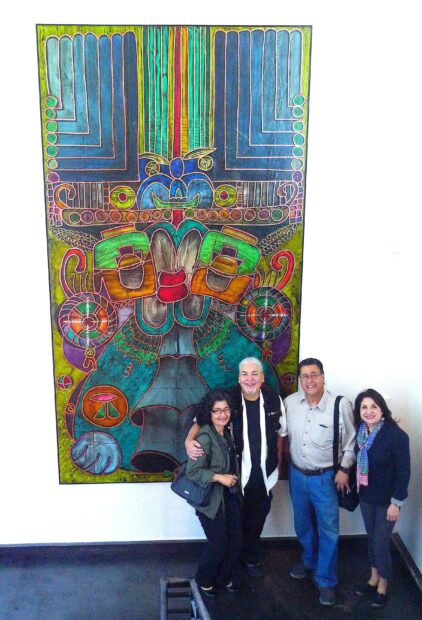

Becky and Roberto Gonzalez, Gilberto and Dolores Cardenas, with “Cocijo,” 2014, 134 x 70 inches, acrylic on canvas). Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

I wanted to include as many paintings as possible in the exhibition, and Cocijo wouldn’t fit anywhere else, so I put it in the stairwell leading to the second floor, just above one section of the Preludes. Cocijo is the Zapotec rain god.

The god’s eyes are surrounded by green and orange-brown forms. The tube-like forms emanating from his mouth represent rain-producing clouds. He wears a collar of quetzal feathers, and, on each side of his head, large ear ornaments rest on his shoulders. Cocijo has a very large headdress, and the lower portion of it forms a smiling face.

Installation shot of “Sacred Waters,” with Roberto Gonzalez and Jesse Borrego in the first gallery, viewed through the freestanding turquoise walls, as we head to the lobby on the last day of the exhibition.

“Ollin” (2016) The Commissioning of a Monumental Painting for the Lobby

Roberto Gonzalez, shot of “Ollin” (2016, 10 x 16 feet, acrylic on canvas) in process in Gonzalez’s studio. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Before addressing the finished painting, I want to explain Gonzalez’s process. In the above picture, Gonzalez has already applied acrylic paint (and some pastel) to the big canvas hanging in the background. He has already painted the plastic sheet beneath him on the ground with multiple colors. Gonzalez has also put a coat of clear-drying acrylic paint on top of the wet paint on the plastic. He is standing on an elevated beam because all of this paint is wet.

Gonzalez is in the process of cutting thin, linear channels (with a custom made knife) through the painted sheet of plastic. His usual practice is to place the sheet of painted plastic on the canvas as it hangs on the wall of his studio. The clear-drying acrylic paint serves as a bonding “glue” that transfers all of the wet paint off of the plastic and onto the canvas. Then he sprays gold (and sometimes copper) paint through the linear channels that he has cut into the plastic (this creates the effect of golden outlines seen in many of the paintings in the Sacred Waters exhibition.

In the case of Ollin, the painting was so large that Gonzalez had to place it on the ground before laying the plastic sheet with wet paint onto it. Usually, it takes a day or two for the wet paint to attach onto a canvas and dry. But in this case, it took a week. Gonzalez knows when a painting is “done” because the top coat of clear-drying acrylic is white until it dries.

Gonzalez was working on many tasks when he began Ollin, so it took about two and a half weeks of part-time work to make the wooden stretcher support, to attach the canvas to it, and to reinforce the stretcher after it had cracked. He painted Ollin in three weeks, while he was also making and framing other paintings. That includes the time it took the painting to dry, before he could remove the plastic and add an important finishing touch to the painting (see discussion of the hummingbird and ear-flower below). Gonzalez had completed 52 paintings the previous year. He had not expended this much time on a single painting in more than a decade, when he last made equally large paintings. Gonzalez began the painting before we had any idea whether the exhibition would be approved, as otherwise it would not have been done in time for the opening.

Installing “Ollin” in the lobby of Centro de Artes, 2016. From left to right: unknown person, Roberto Gonzalez, unknown person cranking up the lift, Henry Arispe (center at top of lift), Joseph M. Bravo, Guillermo Sato, Ron Green. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

I had suggested the theme of the so-called were-jaguar, or transformation figure, as a subject of the painting to Gonzalez, and he enthusiastically embraced the idea.

The passages in italics are from my wall text dedicated to Ollin.

In the indigenous Mexican language Nahuatl, the word ollin means movement, and it is associated with powerful forces, including the sun that moves across the sky, the beating human heart, and earthquakes. The Aztecs called themselves the People of the Sun. They believed that the present world, known to them as the Fifth Sun, was destined to be destroyed by earthquakes, which would end the world until the next cycle of creation brought forth a new one.

Roberto Gonzalez, “Ollin” (detail of figure with jaguar/human head; the gray hands above the black circle reference the goddess Coatlicue; the hummingbird and ear-flower are discussed below), 2016, 10 x 16 feet, acrylic on canvas. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

“I am Ollin,” declares Gonzalez. “The atomized man standing in the center of the picture represents my inner drive for transformation. The aroused were-jaguar face in the central figure expresses the need to connect with my core animal nature as a reminder of my life force.” The Olmecs created many composite human/jaguar figures known as were-jaguars, or jaguar transformation figures. They associated jaguars with water, and the powerful, potentially deadly storms that rained down on their Gulf Coast habitat. They likely analogized the roar of the jaguar with thunder, and they sought to harness the mighty jaguar’s powers.

For a discussion of the were-jaguar/transformation figure literature, see my Glasstire article “Luis Jiménez’s Man on Fire: From the Olmec Were-Jaguar and the Vietnam War to Spiritual Self-Portrait.” Jiménez was also a Jungian artist.

In this painting, Gonzalez is both man and beast. This transformative potential symbolizes “spiritual metamorphosis into a more evolved being.”

The hummingbird drinking from the ear-flower (a Mesoamerican motif) was the last part of the painting that Gonzalez completed (after the paint transfer was complete and after he had removed the plastic). He encountered this motif in articles on Mesoamerican myth. He views the union of hummingbird and ear-flower as “a sign of consciousness and transformation.”

The dark circular void in the man’s chest serves as “the aperture of the unconscious, positioned at the heart level.”

In indigenous thought, consciousness arises from the heart, rather than the head. The cavities that Mesoamerican sculptors carved on statues and masks were filled with precious substances, such as turquoise, jade, or shell. A heart cavity, for instance, would be equipped with a symbolic (ollin / movement-producing) heart — one that could also be excised. For Gonzalez, the cavity he depicted in Ollin is a symbolic entrance to consciousness, situated at heart level. Thus the ear-flower and the heart cavity serve similar purposes for the artist.

Roberto Gonzalez, “Ollin” (detail: Cocijo’s square-shaped eyes are on each side of the black dot, and his fangs are outlined in copper beneath the dot; the man’s body, rendered in ghostly gray, continues down to the tops of the ears of corn at the bottom of this detail), 2016, 10 x 16 feet, acrylic on canvas. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

The swirling black-and-white forms that cover the man’s upper body symbolize the sun and its movements. Secondly, copper [and black] outlines within these swirling forms depict the masked head of Cocijo, the Zapotec rain deity, whose body is formed by the blue-green scales beneath the man’s torso. Cocijo’s water torso in turn feeds the corn at the bottom of the painting. Corn provided sustenance to pre-Hispanic civilizations, and it also stands for the vast array of foods developed by the indigenous peoples of the Americas, which constitute vital gifts to the rest of the world.

For the development and transmission of food from the Americas, see my book chapter: “Indigenous Heritage, Culinary Diaspora, and Globalization in Rolando Briseño’s Moctezuma’s Table,” in Norma E. Cantú, ed., Moctezuma’s Table: Rolando Briseño’s Mexican and Chicano Tablescapes (Texas A&M Press, 2010: 68 – 91).

Roberto Gonzalez, “Ollin” (detail of corn at the bottom of the painting), 2016, 10 x 16 feet, acrylic on canvas. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

Gonzalez’s ears of corn were inspired by an Aztec stone box (the Aztecs called them tepetlacalli, which means stone houses), with four ears of corn sculpted on each of its four sides. It is popularly known as the Corn Stone or the Corn Altar.

Aztec culture,“Corn Altar,” c. 1325-1521, carved volcanic stone with traces of red pigment, 58 x 57 cm, Anthropology Museum, Mexico City. Photo: Ruben C. Cordova.

A large blue, green, and orange atom with yellow rays is situated behind the standing figure. The four circular emblems that swirl around the atom represent the four directions.

An emblem for water is placed at each of the corners of the T’s crossbar. A frog is perched in each of the upper corners. Gonzalez’s father told him that frogs sang for rain because they were thirsty. A stylized representation of Quetzalcoatl (the feathered serpent) inhabits each of the lower corners.

The cruciform shape of the canvas itself represents the four directions. A notch in each of the upper two corners reinforces the small v-notch in the very center. That central v-notch references those found in the middle of Olmec rain baby foreheads. For Gonzalez, this notch symbolizes the left and right sides of the human brain and is the mark of consciousness. He believes that as an artist, refining the quality of his consciousness serves as “the only way forward in my creative liberation.”

Gonzalez concludes: “I am mestizo, a person of many mixtures, therefore I mix varied pictorial, metaphoric and personal elements in this mural.” He has intentionally positioned many of these elements off center to provide an almost imperceptive suggestion of pictorial movement.

Beneath the large ears of corn, Gonzalez inscribed “SANTONYO,” the Chicano slang word for San Antonio, in black graffiti-styled letters.

Roberto Gonzalez, “Ollin” hanging in the lobby of Centro de Artes, 2016, with Ruben C. Cordova, Roberto Gonzalez, and Joseph M. Bravo.

The desk beneath Ollin in the above picture, which is beautifully crafted out of Mexican volcanic stone, is designed to evoke a metate, the traditional Mexican grinding stone that was used to grind corn. It was symbolically appropriate to have four gigantic cobs of corn hovering above the gigantic “metate.”

Roberto Gonzalez, with visitors at the “Sacred Waters” exhibition posing on the gold Dreamstack wall (the white sections on either side housed the Prelude series). Photo: Ruben C. Cordova. I took many photos for visitors to the exhibition, who often posed with the artist as well as the paintings.

Gonzalez visited the exhibition every week, where he conversed with tourists from all over the world. This experience made Gonzalez “realize how important Centro de Artes is.” He adds: “It really is a jewel in the crown of San Antonio and literally the only arts experience most viewers from across the globe have with our culture. So many tourists are only here for a short time. They go to Market Square, and while they are there they see Centro de Artes.”

I have spent a great deal of time at the Museo Alameda/Centro de Artes, where I have curated five exhibitions and was the subject of one solo photography exhibition and a large photography installation (both for Day of the Dead). Through these experiences, I drew the same conclusion as Gonzalez that — for many out-of-town visitors — Market Square is the place tourists go in San Antonio to sample Mexican/Latino culture.

Bravo calls Gonzalez “one of the most talented artists San Antonio ever produced and one of the most genuinely beautiful souls I have ever known.” He says mounting the Sacred Waters exhibition “was one of the proudest moments of my career.”

Gil Cardenas, a Notre Dame University Professor Emeritus (now residing in Austin) and a notable collector of Chicano art, recalls: “I was deeply impressed by the Sacred Waters exhibition and the wide range of beautiful paintings in it. I couldn’t resist purchasing eleven of Roberto’s paintings the day I saw the show. I bought even more works when I visited his studio. I was able to exhibit several of these pieces at the Notre Dame Center for Arts and Culture in South Bend, Indiana, and I am glad that Roberto was able to see them there and at our home when he visited us a year or two later.”

I am grateful that I was able to present Gonzalez’s work with vibrantly colored walls that enhanced the aesthetic and symbolic qualities of his paintings. Sacred Waters wouldn’t have been the same exhibition with white walls.

The lobby of Centro de Artes with white walls and integrated desk / shelf unit, 2018. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

In the years after Sacred Waters, Centro de Artes has been managed by the City of San Antonio. The lobby of Centro de Artes was whitewashed before celebrations for San Antonio’s Tricentennial in 2018. Thus one can compare the effects of white walls to the vibrant colors that were utilized from the opening of the Museo Alameda in 2007 until the Tricentennial.

Dudley Brooks at the Sacred Waters exhibition, 2016. Photograph: Ruben C. Cordova.

This article is dedicated to Dudley Brooks, an activist and supporter of the arts, who passed away this year.

Appendix A: Selected Artist Statements by Roberto Gonzalez

In this selection, the artist progresses from pure formalism to concern with mortality and ancestry.

From the artist’s journal, 1980:

Art must speak for itself. Surface is a taut continuum, whatever happens after that is visual. Free up painting from historicity. Concentrate on interrupted junctures, tautness and shadow.

From the ¡Mira! The Canadian Club Hispanic Art Tour (El Museo del Barrio / San Antonio Museum of Art / Plaza de la Raza), 1984:

Painting is my spiritual drowning. Abstraction in my work is homage to the mysterium magnum. It allows me to recognize the lie between birth and death. The reality of the painted surface opens my eyes in living prayer.

From Tejanos Artistas Mexicano – Norteamericanos (Museo de Arte Alvar y Carmen T. De Carrillo Gil), 1990, p. 24:

I work in a circle which is not round. A duality of signifiers surrounds my hands and eyes when I work. The challenge is to signify without using signs knowable or unknowable; those signs which fall between the thought and the vision is what I pursue.

From the artist’s journal, 1991:

What in painting owes itself to history and what is of its own time and being? Transcendence in art is linked with transformation in self.

From the Amuletos exhibition, Blue Star 8th Annual Artist Exhibition, 1993:

Amuletos are not by nature spiritually pure or precious objects. They are common objects contextualized, empowered, and inspirited by each person’s projection of need or want. Amulets have an animistic pre historic inheritance in our land of our people.

From the Alebrijes exhibition, Blue Door Gallery, 1996:

Alebrijes refers to the Mexican visual art genre of portraying “El Muerte” as animated and celebratory. This tradition historically can be traced back to pre-Hispanic meso-American cultures and also connections can be found throughout the world’s civilizations into pre-history. To organize a mythology for processing the loss of others and self due to death is as old as man.

I am not trying to be spooky or macabre. The pathology of this inherited imaginal world of life and death, “life as death” reveals the cultural soul of my ancestors. This reference has inspired me to translate their poetic resonance within the context of my everyday life and cultural experience.

From the artist’s journal, 2007-2008:

Rio Grande as an ancient metaphor of transformation. Painting not of the mind’s eye but of the painter’s grounding in the body. To make the painters body his best resource. The body as bridge, a way to cross the doorway of the unconscious, the painters ground, open and sacred. A bridge through our history into a new moment. A bridge for healing and finding new life. Use the body to cross just like the ancestors crossed and crossed back. The body as container for the expression of visual grace.

Performance art is about viewing the expression of the singular artist. I think the line differentiating performance art from performance has been the difference of a singular artist or a group. The performance artist may dance but it is not dance. The birth canal as first bridge, the first crossing.

From the artist’s journal, 2008:

As a performance artist, the body must be laid bare either in presence, breath or gesture. While performance by itself is artifice, the moment of expression must be real. You skate on the edge of artifice and at the same time the skating must be present, real and not “performed.” Performance art has had a core charge of validating the form only if the artist is present. Performance art is about viewing the expression of the singular artist. I think the line differentiating performance art from performance has been the difference of a singular artist or a group. The performance artist may dance but it is not dance.

From the Bread and Tortillas blog by Gerard Villanueva, April 14, 2016, quoting Roberto Gonzalez discussing the Sacred Waters exhibition:

The Xicano artist works as an agent to restore our cultural spirit before all is lost, before we all become the same. Being a Xicano artist is and has always been a searching reflex. The search is for cultural attachments. The separation and loss of connection to Madre Mexico has been profound historically. It forced Xicanos to have the need for developing a new selfhood.

From the artist’s journal, 2020, on the influence of pre-Hispanic art:

There has been an implicit drive to find inspiration in pre-Hispanic Art in Chicano artist communities since the days of the first Chicano artists. The pre-Hispanic sensibility was prevalent even in many of the political images made by Chicano painters. Pre-Hispanic art has been a shared resource since its beginning.

The question is: are the ancestors lost forever, or is there a way to be with them, learn from them, create anew from their ground? The answer for me is that you just have to go to them, sit with them, listen and observe.

Connection with the ancestors is connection with self. It means arising out of the dark cloud of genocidal loss and moving forward. Being a Chicano artist cultivates a path through to healing.

Appendix B: Roberto Gonzalez’s Solo Exhibitions and Group Exhibitions

Combining my research on the Con Safo group with Gonzalez’s documents, we have been able to verify that he participated in the following exhibitions in San Antonio: Assumption Seminary (1974, C/S), Saint Mary’s University (1975, C/S), Institute of Texan Cultures (1975, C/S), San Antonio Art League (1975), Trinity University (1977*; 1990) the Carver Cultural Center (1978-1979*; 2010**; 2013*) the Witte Museum (1979), the San Antonio Museum of Modern Art (1979*), the Shown-Davenport Gallery (1982**), The Artists’ Alliance Gallery (1983), the San Antonio Museum of Art (1979; 1984; 1986, 1987), L.A. Heights Alternative Space Gallery (1985), Frame of Mind (1986), Gallery 21 (1986), University of Texas at San Antonio (1991), Tobin Estate (1992), Art Inc (1992), Blue Star Contemporary Art Center (1992, two shows in 1993), Luna Notte Gallery (1996*), Blue Door Gallery (1995, 1997**), Artists’ Gallery (1996, 1997), R Gallery (2012), Salon Sanchez (2014*), Centro de Artes (2014; 2016*; 2019-2020), St. Philip’s College (2016*), San Antonio Public Library (2016), Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center (2018), and Freight Gallery (2019**). (One-person shows are marked by an asterisk, two-person shows with two asterisks, and Con Safo group shows with the C/S emblem.)

We also verified Gonzalez’s participation in the following exhibitions outside of San Antonio: North Texas State, Denton (1974, C/S), the University of Oklahoma, Norman (1974, C/S), Crystal City High School (1975 C/S), College of the Mainland, Texas City (1975, C/S), the Mexic-Arte Museum, Austin (1977), the Polyforum Siqueiros, Mexico City (1982), El Museo del Barrio, New York City (1984), the Plaza de la Raza, Los Angeles (1984), the Museo Carrillo Gil, Mexico City (1990), the American Cancer Society Cattle Baron’s Gala, Rio Cibolo Ranch (2018, featured artist), and the La Peña Cultural Arts Center, Austin (2019, 2020).

Appendix C: Roberto Gonzalez’s Awards and Honors

In 1986, the Indonesian Government rewarded Gonzalez with the Pemerintah Propinsi Daerah Tingkat I Jawa Barat Award for his assistance as a cultural ambassador (for work at the Carver Cultural Center). Gonzalez was a Texas Commission on the Arts Artist in Residence from 1998 to 2002, and an Urban-15 Artist in Residence from 2002 to 2003. The San Antonio Department for Culture and Creative Development designated Gonzalez the “Creative of the Month” for June, 2016. The city printed one of my Sacred Waters exhibition wall texts under the name of one of its employees.

***

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and a curator who has curated more than 30 exhibitions, including ten solo exhibitions by Con Safo group members. His book on the Con Safo group was the first book written on a Chicano art group.

6 comments

Thanks for this most complete and fascinating adventure in mounting this exhibition of an artist that was waiting for his due. Excellent

Thank you, Arielle. It was a great pleasure to work on this exhibition.

Ruben, excellent article. Tour de force. I found the work of Gonzalez riveting, and very much enjoyed the installation, with its range of beautifully colored walls that reinforce and enhance the meaning of the work.

Thank, you Marianne. I’m very grateful to have the opportunity to present Roberto’s brilliant work in Glasstire with numerous color pictures. They enabled me to convey a good sense of his work and of the exhibition.

This article was an education on Roberto Gonzalez’ amazing work. Thank you.

You are very welcome, Karen. Roberto has a very large body of work that deserves much more exposure.