For Part 1 of this three-part series, which introduces Reyes’ work in the context of the Chicano movement and the Chicano Moratorium and makes parallels with the Black Lives Matter movement, please click here.

For Part 2, which covers Reyes and the United Farm Workers union, please click here.

This article explores works by Reyes that address the struggle for political representation and social services in Pharr and San Antonio. It also reviews the “Southern Strategy” and race, concluding with Trump and the 2020 election.

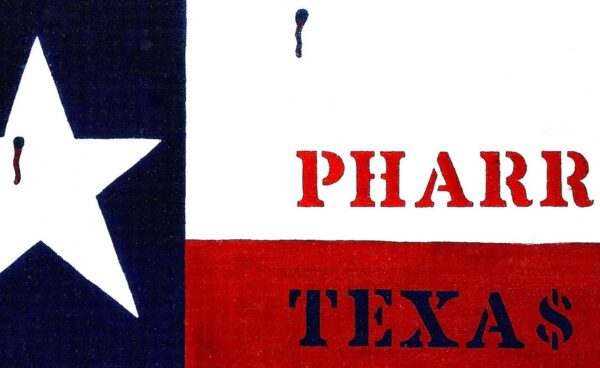

Felipe Reyes (b. 1944), Pharr c. 1971, acrylic on canvas, dimensions unknown. Photograph by Cesar Martinez. Reproduction courtesy of Tomás Ybarra-Frausto Research Material on Chicano Art, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

The entire surface of Pharr replicates the state flag, which is shot through with bleeding bullet holes. The bullet hole in the white star bleeds red, while the others bleed blue, with just a touch of red. These wounds allude to the protest led by the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO) and the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee on February 6, 1971 — a protest that turned deadly. Reyes, Part 2 (see above) explains how the United Farm Workers (UFW) union sparked and fed into the Chicano movement.

Pharr’s previous claim to fame was the destruction of the Church of the Shrine of the Virgin of San Juan by suicide pilot Frank B. Alexander, who crashed a rented plane into it in 1970. See: Pharr From Heaven bog.

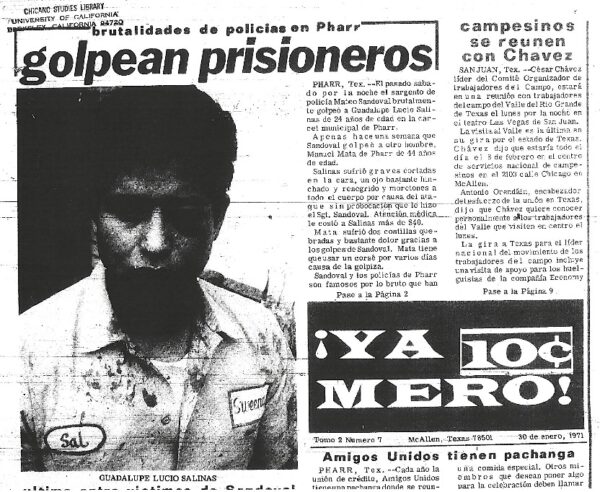

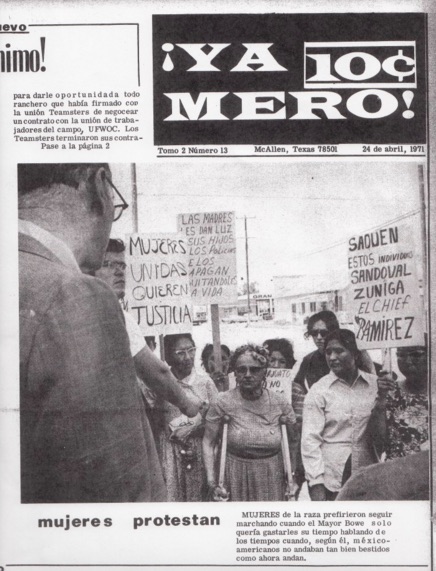

The focus of the February 6 protest was police brutality. On January 30, 1971, ¡Ya Mero!, a Spanish-language paper published in McAllen that circulated in South Texas, featured on its front page a picture of the bloody, bruised face of 24-year-old Guadalupe Lucio Salinas. The article stated that police sergeant Mateo Sandoval had brutally beaten Salinas in the municipal Pharr jail, leaving cuts on his face and extensive bruising on his body. ¡Ya Mero! (1969-1972) was published by David Fishlow, who had previously resurrected El Malcriado, the California-based paper associated with César Chávez and the UFW (see: “‘Ya Mero’ Ends,” Rio Grande Herald, July 6, 1972).

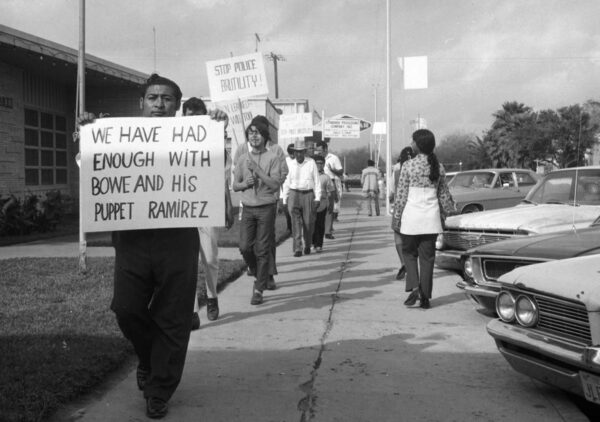

The article noted that the week before, Sandoval had beaten 44-year-old Manuel Mata, breaking two of his ribs. It said the Pharr police were “famous for their brutality.” These accounts spurred indignation and a large turn-out for the February 6 protest directed against mayor R. S. Bowe and his police chief, Alfredo Ramirez, popularly referred to as “Bowe’s puppet.”

About two dozen protesters began picketing across the street from the police station on the morning of February 6, a Saturday. By the early evening, 200-300 people had congregated. Firemen hosed them with high-pressure nozzles. Ramirez had objected to the loud chants of “fuera” (out), which he interpreted as a disturbance of the peace. Ramirez said he called the fire department because he had heard breaking glass. It was caused, he determined later, by two bottles (See Strangers in Their Own Land: The Chicanos, 1971. This ABC News documentary, produced by Hope Ryden, includes commentaries by Ramirez and Fernandez and some footage of the suppression of the demonstration). The protesters were incensed at being hosed and they fought back with rocks. Women procured rocks from their yards and gave them to men (many of whom were coming out of local bars) for them to throw at the police.

Ramirez had a large contingent of reinforcements, including officers from the Texas Rangers (see Reyes, Part 1 and Part 2 for discussions on the Rangers), the Hidalgo County Sheriff’s Office, and the cities of McAllen and Edinburg. Efrian Fernandez, a MAYO organizer and the most vocal critic of the police, was returning to the demonstration at about 6 p.m. when he heard the fire truck sirens. Within minutes after the firemen began hosing demonstrators, says Fernandez, the police began firing volleys and dispersing the crowd (he mentions .38 revolvers; Ramirez said he fired his shotgun). Jaime Garza, who was a 15-year-old member of a teatro group, attributes the start of the riot to a rock thrown by a demonstrator (“Pharr Riot, Part Two,” 2015, Civil Rights in Black and Brown Interview Database).

Snapshot of Alfonso Loredo Flores, with his wife, Lidia Ruiz Flores. Photograph from Cassandra Nichole Garcia. Source: Pharr From Heaven blog.

The police fired numerous live rounds, one of which killed 20-year-old Alfonso Flores, who was shot in the head after he had exited the Ramos Hair Styling Center, where he had gone for a haircut. One witness said deputy sheriff Robert Johnson took aim directly at Flores, but Johnson was subsequently acquitted of negligent homicide two years later (the bullet was too deformed to link it to his gun). About 40 demonstrators were arrested. Witnesses said police targeted people with long hair. In March, a thousand people marched from the basilica to Flores’ grave.

The police also utilized tear gas on February 6, but the demonstrators — particularly a tall, hirsute man called Grizzly — threw the canisters back at them. (Recently, Black Lives Matter demonstrators have used hockey sticks to swat tear gas canisters back at police.) Finally, Garza recalls, 100 armed policemen, sheriffs, and Rangers were lined up against youthful demonstrators on a side street, in front of a church building, where women of all ages (“señoritas, señoras, y viejitas, y todo”) were playing bingo (“popular amongst our people,” says Garza). The “stand-off” was broken when “the ladies from the bingo” came with outstretched arms, stood in front of the demonstrators, and told the police: “Leave them alone.” Who knows what violence might have transpired without this intercession, which made me picture a South Texas version of Jacques-Louis David’s Intervention of the Sabine Women. Women had been involved in the Pharr demonstrations from the start, and after February 6, they took the preeminent role.

As Fernandez noted in Strangers in Their Own Land: “We knew it even before we started that … if you try to organize Mexican Americans in South Texas, you are going to get hurt…. I have suspicions that this riot was rigged by law enforcement officers … I smell a conspiracy from the top.” Participants in the demonstration agree that the use of fire hoses, tear gas, live ammunition, and the involvement of 100 or more officers were unnecessary, and were part of a pre-planned demonstration of overwhelming force whose goal was to intimidate critics of police brutality.

Maria Magallan, an organizer of the February 6 protest, was familiar with police brutality because a young neighbor of hers had been severely beaten. When Fernando Ramirez was five or six, he witnessed a policeman shoot and kill a handcuffed man: “…and then they left him there, as a message to the community.”

“It changes you,” he recalls tearfully, “And that was the normal. It was O.K. They could do that” (“Fernando Ramirez Discusses Police Brutality in Pharr, TX,” 2016, Civil Rights in Black and Brown Interview Database). In another interview, Ramirez says that on the evening of February 6, 1971, he was returning from a date. When he was at a stop sign, a policeman put a shotgun to his head and told him he would shoot him if he didn’t stop at the house where he said he lived. Ramirez’s experiences exemplify a point I made in Reyes, Part 1: violence and the threat of violence were among the means necessary to subjugate a disempowered majority.

Magallan founded the women’s group Union y Fuerza (union and strength). Susan Law identifies Magallan and Raquel Orendain of the UFW as the leaders of the subsequent stage of protest. A press release issued on April 16 said 150 women had unanimously voted to picket 12 hours a day until the offending officers were removed. It also mentioned a boycott (discussed in more detail below). It was assumed — and this proved to be the case — that law enforcement officials would not beat women or shoot at an assembly of women, because such actions would have led to open revolt (see: Eduardo Martinez, “The Open Wounds of the Pharr Riots of 1971,” Pharr From Heaven blog, October 30, 2019).

Front page of ¡Ya Mero!, April 24, 1971. Women confront Bowe with signs that say: Mujeres Unidas want justice; mothers give light and the police extinguish life; fire Sandoval, Zuñiga, and chief Ramirez.

Women picketed Pharr City Hall, the police station, and Bowe’s home.

Women with placards (probably at city hall) calling for fair elections and the removal of Sandoval, Zuñiga, and Ramirez, Pharr, TX, 1971.

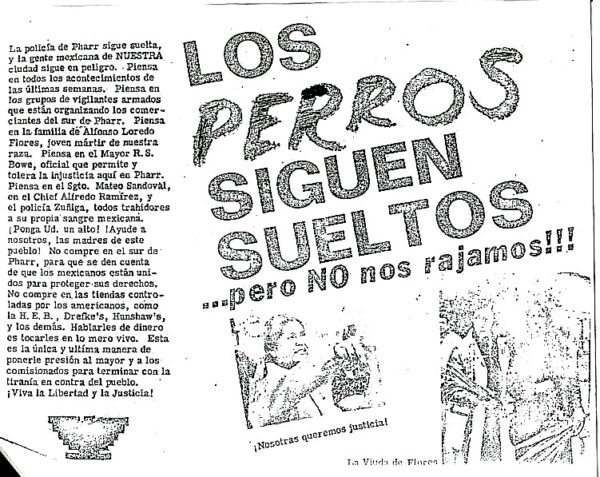

“Los Perros siguen sueltos… pero No nos rajamos!!!” (These Dogs remain loose, but we will not back down), mimeographed flyer, Pharr, TX, 1971. Source: StoryMapJS: Pharr Riot.

This flyer states that because the police are free, the Mexican people are in danger. It calls Sandoval, Ramirez, and Zuñiga “traitors to their Mexican blood.” It calls for a boycott of stores in the south section of Pharr (whites lived south of the railroad tracks, Blacks and Mexicans to the north of them), deeming it “the only and ultimate manner” of ending the “tyranny against the people.” As noted in Reyes, Part 2, the UFW eagle came to symbolize the Chicano movement. Since UFW organizers played an important role in the Pharr demonstrations, it should be no surprise that UFW imagery and tactics were employed.

Bowe, Ramirez and other officers, and four city commissioners resigned within a few months. Fernandez highlighted Bowe’s “rigid grip” on power and his “clever use of rewards and punishments” in his “Community Organizing in the City of Pharr” (1974): “the full power inherent in city government was used and abused to the hilt. This included corruption in the police, the water department, the tax department, the city inspector’s department, and even in the staff of the city offices” (cited in Martinez, “The Open Wounds of the Pharr Riots of 1971.” For maps, and a chronology and bibliography, see StoryMapJS: Pharr Riot.) Ned Wallace, who wrote his dissertation on this subject, calls the Pharr Riot “a turning point” in Rio Grande Valley (RGV) history (as quoted in The Brownsville Herald in 2016).

Soon thereafter, Pharr and other RGV towns elected Mexican American/Chicano mayors and other officials. The Pharr barrio finally received essential services, such as adequate water lines, sewage lines, paved streets, and streetlights. Wallace notes that when the barriers that had preserved their second-class status were dismantled, the majority population of the RGV finally became integrated into U.S. society.

MAYO leader Efrain Fernandez was charged with malicious destruction of property and “engaging in a riot.” Fishlow, speaking for the Texas Civil Liberties Union, notes that ten Chicanos were wrongly arrested while “engaged in the kind of peaceful protest guaranteed to all citizens” (“Ten Chicanos to Get A.C.L.U. Aid,” New York Times, September 26, 1971).

In a momentous victory, Fernandez was eventually cleared of all criminal charges leveled against him. Many factors prevented Chicanos from attaining justice through the courts. The Strangers in their Own Land video cited above notes that while Texas law required six years of schooling to meet the literacy requirement for jury duty, the average adult Mexican American in Hidalgo county only had 3.3 years of schooling. Endemic poverty forced children to help support their families, and to forego educational opportunities that might help them break out of poverty. Many of Fernandez’s witnesses were migrant workers — luckily, he was able to get his trial rescheduled to a date when his witnesses were in town. Wallace concludes that Fernandez’s acquittal “was the first demonstrable time in Rio Grande Valley history that a Mexican-American had successfully confronted the ‘system’ through the law courts and prevailed.”

In Pharr, Reyes references an event that had momentous significance: a single act of violence precipitated the political transformation of the Rio Grande Valley. Reyes has substituted a $ for the S in TEXAS, in recognition of the accumulated wealth and entrenched economic power that produce political, judicial, and carceral power. These powers often thwart popular will and majoritarian rule.

Reyes gave this commentary in Magazín in April of 1972: “What happened in Pharr was physical genocide; this was brutality on the physical level. This painting represents a tribute, on my part, to the people who fought there for LA CAUSA.” In a recent conversation, Reyes recalls that the struggles in Pharr were continuously in the news. They were also a primary topic of conversation within the Con Safo group (see Reyes, Part 2) and the Chicano community in San Antonio, “especially because we had testimony that contradicted the mainstream news media coverage.” Reyes emphasizes that “a solid political base” and “reliable news sources” are neccessary for a successful movement.

In July of 2020, a “Wall of Moms” formed to shield Black Lives Matter protesters from federal troops in Portland, Oregon. Kelsy Kretschmer discusses precedents for this action, including the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo, who began protesting in Argentina in 1977 because the military junta had “disappeared” their children (“Video: the Wall of Moms builds on a long protest tradition,” The Conversation, August 11, 2020). The significant role that women played in the Pharr uprising is not generally known outside of South Texas, and it deserves to be placed in the larger context of political protests led by women. Trump’s troops beat the Portland moms, and fired tear gas and “less lethal” weapons at them. Thus they were more violent than the South Texas police forces in Pharr in 1971, and more violent than many notorious authoritarian regimes that have refrained from attacking peaceful female protesters.

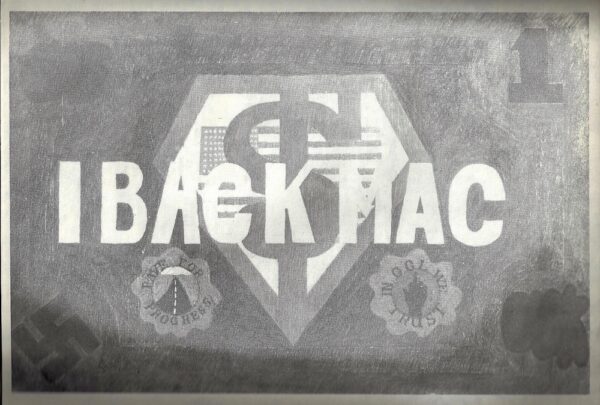

Felipe Reyes (b. 1944), Fast Buckaroo Politics, c. 1972, acrylic on canvas, dimensions unknown, location unknown. Photograph by Cesar Martinez. Reproduction courtesy of Tomás Ybarra-Frausto Research Material on Chicano Art, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

In Fast Buckaroo Politics, Reyes takes caustic aim at San Antonio’s power structure, specifically at Mayor Walter M. McAllister (in office 1961-71) and his nearly indomitable political machine, the Good Government League (GGL). Richard Gambitta, in his capsule history of San Antonio government written for the San Antonio Express-News in 2015, notes that McAllister began efforts in 1948 to restructure the city’s government so that it would better serve business elites. He found success in 1951, when the council-manager system was approved. Rather than representing specific districts, council members were elected at-large and were paid almost nothing. Chamber of Commerce President Tom Powell and McAllister formed the GGL in 1955 to control this city council. McAllister was also controversial as the owner of a segregated business, as someone who utilized stereotypes, and as a red-baiter, as I discuss in my book Con Safo: the Chicano Art Group and the Politics of South Texas (2009).

Gambitta characterizes the GGL as an entity made up “predominantly of North Side Anglo elites.” Rodolfo Rosales, in his The Illusion of Inclusion (2000) surveys the GGL, its opponents, and its successors. Rosales points out that between 1955 and 1971, the GGL, with a slate of 78% Anglo candidates, won 77 of 81 city council races and exerted a political stranglehold on the city. The city government also controlled the water works, the public bus system, the power utilities, the urban renewal agency, and the housing authority.

Reyes’ critique takes the form of an ersatz dollar bill. The pentagonal shield in the center is inscribed with an enormous “S” that doubles as a dollar sign and as a mocking allusion to Superman. It also reads as a baseball “home plate,” signifying local corruption. The U.S. flag summons the expression “patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel” and also points to the national arena. Consequently, it is not too much of a stretch to view the pentagon as THE Pentagon, signifying military aggression as well as monumental economic waste. Because of their fervent anti-union sentiments, San Antonio’s ruling elites courted military bases rather than private corporations and industries. Military funding was a hot issue among Chicanos in San Antonio, as it was elsewhere (see Reyes, Part 1). In 1970, activist City Councilman Pete Torres castigated representative Henry B. Gonzalez for his support of military funding bills; this led Gonzalez to throw his support to John Gatti (more about him below), who defeated Torres in the 1971 city council election. (For the Torres-Gonzalez conflict, see The Texas Observer, Dec. 12, 1980).

Reyes provided this commentary in Magazín in 1972: “Fast Buckaroo Politics concretizes the concept of the American government and its white muscles, which include politics, economics and culture. The U.S. government segregates Chicanos and then oppresses us. Thusly, this painting is a painting of that oppression. Concerning the title, buckaroo here has 2 meanings: dollar and rural, western America… [ellipsis in original] thus the fast buck, the swindler, the all-American superman, the Nazi.”

Reyes superimposed the slogan “I BACK MAC” in lily white across the face of his fake bill. This implies that McAllister’s political currency is likewise a “counterfeit.” The white paint associates McAllister and the GGL with white power, though the GGL regularly included somewhat tokenistic candidates of color, providing “visibility and ego input,” according to “a GGLer” quoted by David Montejano in Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986 (1987). “I BACK MAC” parodies the most famous simple-rhyme political slogan of all time, Eisenhower’s “I Like Ike.” Reyes’ mock slogan implies that McAllister is “backed” by money (literally as well as figuratively). Reyes weaves a large web of multiple associations and political positions. One can interpret the “one” at the top and the swastika at the bottom in accusatory combination: as “one Nazi,” just as the other corners combine to form “one buck.” The title Fast Buckaroo Politics carries associations of corruption, profit motive, and short-term interests. Since “buckaroo,” which means cowboy, is a corruption of the Spanish word vaquero, it also implies incomprehension, colonization, and whiteness on a cultural level.

The two emblematic green logos on either side of the pentagon echo the U.S. Great Seal, whose obverse (eagle and shield) and reverse (unfinished pyramid with eye) are illustrated on the back of the $1 bill. They specifically mock McAllister and his league. The slogan “In GGL We Trust” mimics the inscription found on U.S. coins, but substitutes the GGL for God. For further emphasis, a central dark hand flips-off the putatively all-powerful GGL. The “Pave for Progress” logo features a blacktop road that extends to the horizon, with empty green expanses on either side. It literalizes the expression “road to nowhere.” Or, alternatively, it is the GGL’s pet project, a highway ultimately named after McAllister that was carved through literal parkland in the very heart of San Antonio. Reyes’ logo alludes to the construction of highways, whose purpose was to spur development to the rural north, away from the downtown area, with its adjoining Chicano and Black neighborhoods. Enormous paving, drainage, and other development projects dramatically raised the price of Northside real estate, and it brought enormous profits to developers and speculators.

Having failed to secure studies and approval to cut through public parkland, San Antonio “highwaymen” (I applaud Texas Monthly’s use of this term in a 1973 article) nonetheless began building both ends of the Northside expressway (connecting downtown and the airport), certain that they could not be stopped once they reached the park. Federal court rulings repeatedly stymied them, causing Mayor John Gatti to invoke “state’s rights” in 1971. The highly frustrated, septuagenarian back-room-highway-broker Walter McAllister played the trusty Texas trump card, declaring that he was “about ready for Texas to secede from the Union.” One could almost imagine him at the Alamo, shouting: “Give me my highway, or give me death.” In 1973, Texas senators sponsored the Federal-Aid Highway Act, which allowed the project to proceed, as long as it did not use federal funding. Conservationists took the fight all the way to the Supreme Court. The last legal challenge was exhausted in 1974, and the McAllister Freeway (a stretch of US 281) finally opened in 1978. It was the most controversial freeway ever constructed in Texas, and one of the most controversial and costliest in the nation. It was discussed in the New York Times, in Helen Leavitt’s anti-freeway book Superhighway-Superhoax (1970), and in David Dillon’s The Architecture of O’Neil Ford (1999). Ford was a leading critic of the highway and an advocate of parks and city centers.

The city’s directional destiny had been cemented in 1970, when the soon-to-be-built University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) was hijacked. The decision was made to situate it 20 miles north of the city-center site originally planned for it, where it would have adjoined ethnic populations, revitalized the downtown, and transformed the city in many positive ways. Gambitta notes that in addition to UTSA, the UT Health Science Center, the South Texas Medical Center, and USAA were all situated in the far Northwest. The city did build an $11 million convention center (1964) and a $5.5 million Tower of the Americas (1966) in the center, but it refused to pave streets, prevent flooding (which could be deadly), and perform other necessary services in the barrios. Reyes was very cognizant of what was at stake in all of the machinations that transformed the city for the benefit of speculators and for a small, moneyed elite, at the continued expense of the populace as a whole, and of people of color in particular.

The first state of Fast Buckaroo Politics — as it appeared in Magazín in 1972 (below) — is very different from the one reproduced above.

Felipe Reyes (b. 1944), Fast Buckaroo Politics c. 1972, acrylic on canvas, dimensions unknown, location unknown. Photograph by Cesar Martinez, as reproduced in Magazín in April, 1972.

The painting in its early state is lightly sketched-in, with brushstrokes that recall the grass in Sacred Conflict. It is so flatly rendered that it looks like it could have been painted in gouache. In the later state of the painting (taken from a slide in the Archives of American Art), the entire surface is covered with thick impasto. Reyes likely considered the painting to be finished when it was reproduced in 1972. During this stylistically experimental stage, he give it a thickly-painted “make over.”

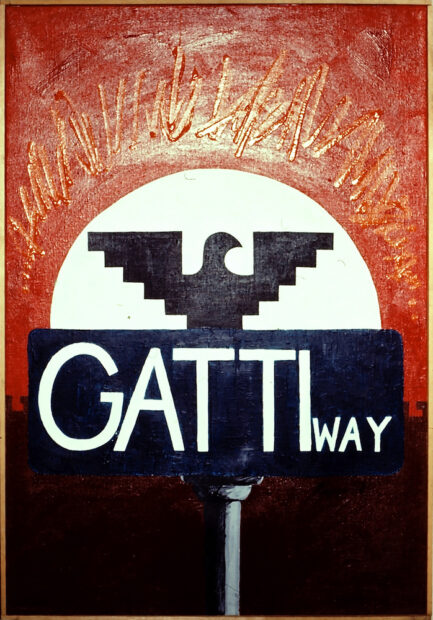

Felipe Reyes (b. 1944), The Rising Star of San Juan, c. 1971-72, acrylic on canvas, dimensions unknown, location unknown. Photograph by Cesar Martinez. Reproduction courtesy of Tomás Ybarra-Frausto Research Material on Chicano Art, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

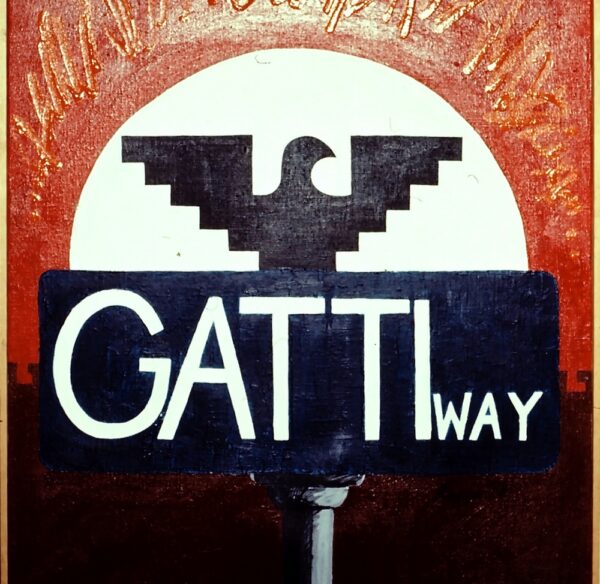

Reyes provides this analysis in the April, 1972 issue of Magazín: “Street sign by San Juan homes which are a housing project for Chicanos. The painting depicts the cultural imperialism of Anglos on the Chicano community. It is also further evidence of the primitive and colonial state of the Chicano people.”

I found no current trace of Gatti Way in San Antonio, though it appears in old records. I haven’t been able to determine if the street name is connected to the family of John Gatti, the GGL politician mentioned above in connection with Fast Buckaroo Politics. Gatti defeated Pete Torres in the 1971 city council election (for the complex intrigues that led them to compete for the same slot, see: “Paul Thompson” [column], San Antonio Express and News, March 7, 1971). Gatti was subsequently elevated from the city council to the position of mayor.

In the early 2000s, Reyes interpreted this painting as a critique of John Gatti and the GGL: “Gatti is its rising star.” Reyes makes the street name into a compound word: GATTIway. This implies an authoritarian disposition to have things his way, to bulldoze opposition, like the GGL juggernaut plowed over opposition to the McAllister Freeway. The UFW flag serves as the landscape’s background. Reyes juxtaposes competing visions of “progress.” For the GGL, progress consists of highways heading north; for Chicanos, progress is the Chicano movement, symbolized by the UFW. The UFW “rising sun” is ushering in a new age: the ascendancy of the Chicano, symbolized by the eagle, which threatens to eclipse the “Gatti way.” Humorously, the eagle seems to be perched on the street sign, as if it already has Gatti in its clutches. This new age of the Chicano also heralds the “twilight” of the GGL.

Historically, the GGL was close to the end of its road. It suffered from internal tensions (exacerbated by excessive northward development) between the downtown Chamber of Commerce and the Northside Chamber. As David Montejano notes in Quixote’s Soldiers (2010), the lack of “major infrastructural improvements” for 30 years in the west and south sides of town (among other factors) fueled discontent that could no longer be contained. The GGL was successfully challenged by westside Chicano insurgents in 1969 (including Torres) and 1971. In 1973, it lost the mayor’s office for the first time. The GGL was defeated soundly in 1975, and it disbanded altogether in 1976. As Gambitta puts it, “the GGL machine had not been geographically or class inclusive, or equitable in service delivery.” Those inequities also had a pronounced racial dimension.

Rosales explains how city council representation was changed. The Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF) challenged the San Antonio city council’s at-large structure. The Justice Department gave MALDEF a favorable finding in 1976 (through the expanded Voting Rights Act, the recent annexations north of the city were found to dilute the Mexican-American vote). San Antonio had three choices: to de-annex the nine precincts that were recently added; to create individual city council districts; or to appeal the decision in court. The city council narrowly voted to create specific districts for individual councilmen, and this decision was ratified in a referendum. Rosales points out that this structural change “created and institutionalized for the first time an independent voice from the various communities in San Antonio’s non-northside areas.” As in the Rio Grande Valley — discussed above in connection to Pharr — Chicanos in San Antonio did not achieve substantial local political representation until the 1970s. Only then was it possible to have even a somewhat equitable distribution of city services and resources.

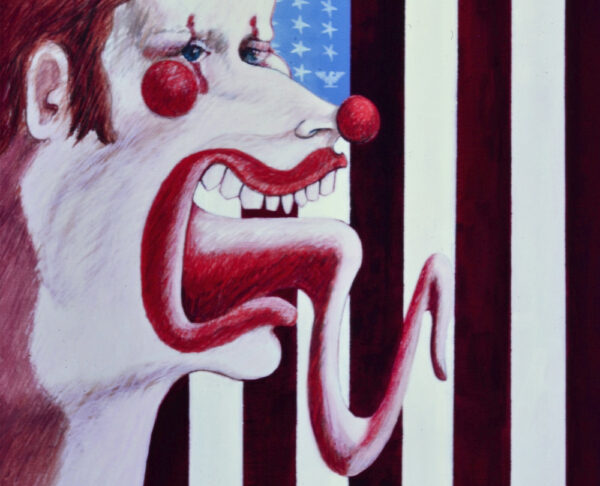

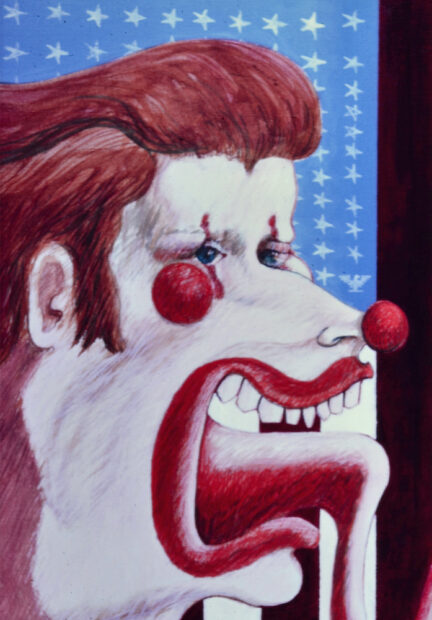

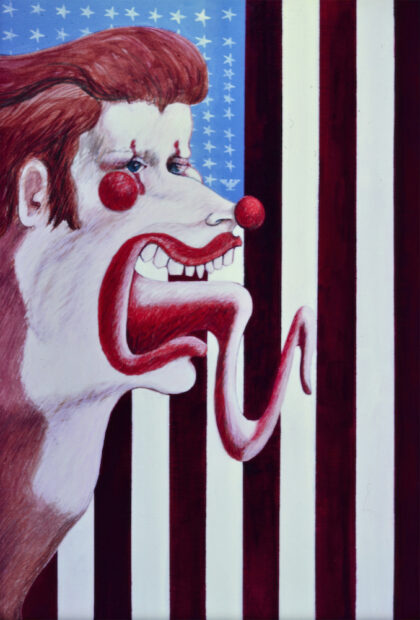

Felipe Reyes (b. 1944), El Lambiache (derived from the word for lick, it would translate as The Kiss-Ass, Ass-Licker, or Brown-Noser), c. 1972-73, acrylic on canvas, 36 x 24 inches, collection of the artist. Photograph by Cesar Martinez.

El Lambiache, a more stylistically mature painting, was likely completed after Magazín went to press. Martinez photographed it before Reyes departed for graduate school in Michigan in the Fall of 1973.

In El Lambiache, Reyes reserves special venom for servile accommodationists of Mexican descent who “tried to pass for white.” Instead of Chicano, they likely would have preferred to be called Hispanic, or even Spanish. Here it is instructive to recall Rubén Salazar’s discussion “Who Is a Chicano? And What Is It the Chicanos Want?” in the Los Angeles Times (February 6, 1970). Salazar declares: “A Chicano is a Mexican-American with a non-Anglo image of himself.” He notes that the barrio term “Chicano” is “an act of defiance and a badge of honor.” Salazar also points out that while Los Angeles has the most Spanish speakers of any city, this constituency has no representation on the city council. Tragically, Salazar was killed by a policeman on the evening of the Chicano Moratorium, August 29, 1970 (see Reyes, Part 1).

The character Reyes rendered in El Lambiache is not a particular person, but rather a caricature of a social type. He is a traitor who is eager to appease. He is expecting to benefit or profit from the accommodations he makes with power holders. As the artist told me in the early 2000s, the “clown-like whiteface denotes the masquerade of the betrayer and the cultural saboteur.” In his interview with Carmen Lomas Garza in the December, 1971 issue of Magazín, Reyes states: “Institutions try to impose cultural imperialism on Chicanos. They try to make brown people into brown whites.” Here the lambiache’s face has been transformed from brown to faux-white. In a recent conversation, Reyes recalls that he also made a sculpture (location unknown) of a man “taking his white skin off and showing his brown skin underneath.” Reyes, in the Magazín interview, states: “We have to define ourselves. We have to define los vendidos (the sellouts), etc.” In a recent conversation, Reyes notes that tio taco (Uncle Tom) was the traditional term used for the social type he portrayed in El Lambiache. For Reyes, the lambiache was a sellout, a tio-taco, a type that needed to be defined and depicted.

The lambiache’s face is whitened and he wears a red rubber clown’s nose. His reddened cheek is so discrete and emphatic that it rhymes with his clown nose. He has blue eyes, and — like other clowns — red vertical and horizontal lines that accentuate them. His lips are also broadly rouged. But — as one expects of a lambiache — his most remarkable attribute is his enormous, servile, serpentine tongue. This tongue and the large mouth that houses it derive from Ed “Big Daddy” Roth’s Ratfink, without its giant ears, bloodshot bug-eyes, sharp teeth, and green or blue skin. The lambiache’s clownish whiteface masquerade is meant to be ridiculous. Reyes told me in the early 2000s that he wanted “to shed light” and expose beings “that always scurried in the dark corners while they caused harm to the community.” Lambiaches were secret informants who lurked in the shadows because they were ashamed of their own acts of betrayal. Reyes added: “I wanted to create as many levels of doubt [about this character] as possible.”

In a recent conversation, Reyes specified that lambiaches “always side against Chicanos and defend Anglos.” He notes that social programs that “would have created a benefit for the community always got choked off by the lambiaches.” The artist has always declined my requests to identify specific individuals as lambiaches. “I don’t go there because people change,” he told me in our most recent conversation. “They can and do change.”

The U.S. flag in the background has dark stripes — like dried blood — instead of true red. Unlike the lambiache’s bright blue eyes, its blue field is bleached. Not coincidentally, Reyes’ lambiache — this double agent in the service of the dominant culture — is such an assimilationist that he is more red-white-and-blue than the flag behind him. As Reyes explained in the early 2000s: “The U.S. flag was a hollow symbol for us — it did not deliver on its promises because of the people who stood between us and the flag,” here symbolized by the lambiache. In the corner of the light blue field, just above the clown’s nose, one can see that a tiny eagle replaces a star. Reyes elaborated: “For Chicanos, the UFW eagle was the symbol of freedom and opportunity.” The eagle on this flag is a sign that Chicanos are carving out a space for themselves on the fabric of the nation.

Conclusion

After Reyes’1972 spread in Magazín, with its six paintings, one lithograph, and one extremely valuable page of period commentary, this body of work garnered little attention. I discussed several paintings and illustrated Instant Genocide and Sacred Conflict in my Con Safo book in 2009. Sacred Conflict figured prominently in my catalogue The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth (2018), where, as far as I know, it was the first of the ten paintings in these three Glasstire articles to be reproduced in color. I have not seen previous publications in which Southwesterly Winds, Lettuce Prey, Huelga, and El Lambiache have been previously reproduced.

In recent discussions, Reyes expressed satisfaction at seeing color reproductions of these works, most of which he has not seen since the early 1970s. He wonders which ones still exist, and where they might be located. Reyes also notes that these paintings address the Chicano community because they were made for and advocated for a barrio audience. He recalls that he and his artistic peers were very concerned with concientización (becoming aware politically). Reyes says the exhibitions in which he participated were very enthusiastically received by the community. “They were the first exhibitions in San Antonio to reflect and advocate for the community,” he recalls. They sometimes received negative responses “from other constituencies” because, he points out, “they were against us from the start.”

Reyes also notes that these paintings lacked the “advanced picture-making skills” he developed in graduate school. “The craftsmanship was not as good as I would have liked it to be,” he adds. Of these ten works, Reyes is most satisfied with Southwesterly Winds (treated in Reyes, Part 1). He notes that the title refers the Dylan lyric “You don’t need to be a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.” Reyes “associated the revolutionary hippies know as the Weathermen with the Pachucos” (a stylish, rebellious Chicano subculture that wore zoot suits and spoke caló).

I solicited comments from several San Antonians to provide additional perspectives on Reyes and his work. Artist Cesar Martinez moved to San Antonio in the spring of 1971 and quickly became acquainted with Reyes, who was an undergraduate. Martinez recognized Reyes’ “maturity and technical depth,” which he thought rivaled that of more established artists. “Though we were all trying to express these new ideas that were entering our political and cultural consciousness,” recalls Martinez, “I would say that Felipe’s work was the most politically on target, very topical.” He also notes that Reyes utilized “different modes of expression. He could be illustrational, expressionist, and abstract, you name it.” Through his friendship with Magazín’s editor, Cecilio García Camarillo, Martinez was instrumental in getting Reyes’ work into Magazín.

Ellen Clark, a professor emerita in Bicultural Bilingual Studies at UTSA, encountered Reyes’ work circa 1972, when she and Reyes were undergraduates at Trinity University. She says his “thought provoking” work contributed to her “lifelong commitment to understand the effects of racism, exclusion, lack of education and resources, time, and space on our being.” Clark recalls receiving “slaps on the wrist” for using Magazín and Reyes’ work in her classes, which were deemed “controversial.” She notes they were very effective in stimulating, inspiring, and provoking student research.

Gabriel Quintero Velásquez, Executive Director of the Avenida Guadalupe Association, met Reyes in the late 1990s. He emphasizes that Reyes’ paintings “represent one of the first emergences of the Chicano voice against racial and political injustice.” Velásquez adds: “Felipe’s influence was far-reaching, as an artist, as an organizer, and as a visionary, stretching all the way into the current era.”

I hope I have adequately explained these trenchant, hard-hitting paintings, including the degree to which they were attuned to period struggles and events. These foundational exemplars of politically committed Chicano art constitute the most potent and caustic political critiques Reyes ever created. As products of his political awakening, they burn with the heat of that originatory fire, and are largely unmediated by other concerns. Reyes launched them like a Kamikaze pilot, and not many traces of these vehicles are known to have survived. Hopefully more of them will resurface, and his contribution to Chicano art and culture will be better appreciated, especially outside of San Antonio. His central role in the formation of the Con Safo art group will be discussed in a future Glasstire article.

Racism, The “Southern Strategy,” Trump and the 2000 Election

In Part 1, Reyes noted Trump’s racism and judged him one of the nation’s worst presidents. He points out that that Mary Trump, the president’s niece, refers to him as “the world’s most dangerous man” in the subtitle of her new book, Too Much and Never Enough (2020). Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer called Trump “the biggest threat to the American people” (The Detroit News, September 10, 2020). Senator Bernie Sanders, who cites increasing authoritarianism, inadequate health care, the pandemic, inequality, climate change, and other issues, says this is “an unprecedented moment in American History.” He calls Trump “the most dangerous president in the modern history of this country.” Noam Chomsky, primarily because of climate change and the threat of nuclear war, calls Trump “the most dangerous figure in human history.” He points out that not even Hitler posed the threat of “destroying organized human activity. There has been nothing like this.” Chomsky adds: “The Republican Party today is the most dangerous organization in human history.” Consequently, he deems the 2020 election “the most significant election in history.” (“Noam Chomsky: Decades of ‘the Neoliberal Plague’ Left U.S. Unprepared for COVID-19 Outbreak,” Democracy Now!, July 30, 2020.)

How did our present situation develop? A key factor was the realignment of the South from Democratic to Republican. Republicans achieved this partisan shift via a long courtship of Southern voters called the “Southern Strategy.” Though it was sometimes overtly and proudly racist, it often utilized racially coded phrases, dog whistles, and symbolic actions.

Barry Goldwater laid the foundation for the Southern Strategy in a 1961 speech, when he declared school integration a state concern, ceded the Black vote, and espoused “hunting where the ducks are” — the white vote in the deep South. In 1964, Goldwater repudiated Eisenhower’s legacy on desegregation. He vanquished the “liberal” Rockefeller wing of the Republican Party by winning the support of nearly every Southern delegate, and he set the party on its extreme rightward direction. While Goldwater won only five deep South states and his home state of Arizona in the 1964 election, he provided an ideological framework for the Southern Strategy and he demonstrated its potential. Richard M. Nixon rode it to victory in 1968, despite the independent campaign of segregationist George Wallace, who won five Southern states. Nixon aide Kevin Phillips noted: “Who needs Manhattan when we can get the electoral votes of 11 southern states?” Nixon’s point man was Harry Dent, described by Time in 1969 as someone liberals regarded as “a Southern-fried Rasputin in the Nixon Administration” (“Nation: Up at Harry’s Place,” Time, July 11, 1969). Between Kennedy in 1960, and Obama in 2008, the only Democrats who won the White House were Southerners (Johnson, Carter, and Clinton).

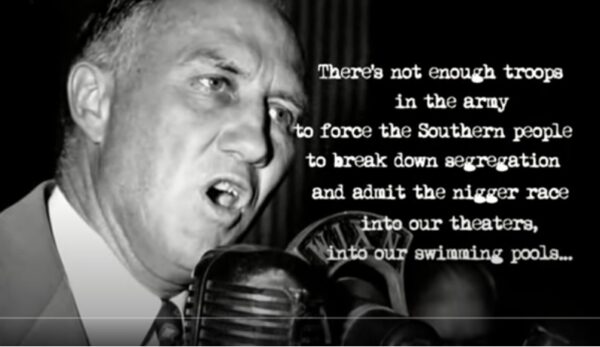

Senator Strom Thurmond, screen grab from Boogie Man: The Lee Atwater Story, directed by Stefan Forbes, 2008. The quote is from the 1948 State’s Rights Democratic Party (a.k.a. Dixiecrat) Convention. The party arose in opposition to President Eisenhower’s support of integration. Thurmond, its presidential nominee, won four states in the 1948 election.

Dent was the confidant of South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, the racist hard-liner who co-authored the neo-Confederate “Southern Manifesto” in 1956. Michael O’Donnell referred to Thurmond in 2012 as “a ghastly King Lear with pitchfork and noose” and notes his presence “at all the major choke points of modern conservative history:” the Dixiecrats (1948); Goldwater (1964); Nixon (1968); Reagan (1980s) (see: “A Malevolent Forrest Gump,” Washington Monthly, September / October 2012).

Thurmond filibustered the 1957 Civil Rights Act for a record 24 hours and 18 minutes, and his racism led him to become the first Southern senator to flip to the Republicans in 1964. Importantly, as Joseph Crespino notes in his biography Strom Thurmond’s America (2012), Thurmond was the first to merge the “politics of white supremacy with southern business and industrial opposition to the New Deal.”

At the 1968 Republican Convention, Nixon won the support of a Southern block assembled by Dent by promising to appoint sympathetic Supreme Court judges and by allowing Thurmond to choose his vice-presidential candidate. Steve Jarding and Dave Saunders credit Dent as the point man of the Southern Strategy and identify South Carolina textile magnate Roger Milliken as its “sugar daddy” (Foxes in the Henhouse, 2006). South Carolina was the epicenter of the Southern Strategy: Thurmond was its key ideologue; Milliken its financier; Dent and Lee Atwater its most important political operatives.

While Thurmond was a proud, transparent bigot, Dent and Atwater were the slippery operatives who guided Dixiecrats into the Republican fold. Rick Perlstein notes how, after Nixon’s nomination, Dent “ran the ‘Thurmond Speaks for Nixon-Agnew’ committee, which was ostensibly ‘independent’ of the official campaign, lest Nixon be excoriated by pundits for campaigning in the South, as one internal memo put it, ‘in regional code words’” (“Harry Dent, b. 1930, The Southern Strategist,” New York Times Magazine, December 30, 2007). Jarding and Saunders say Nixon would likely have refrained from the “race-baiting issues” that Dent deployed so effectively.

After the election, Dent cryptically assured Southerners that Nixon would not enforce federal Civil Rights laws, while — as Perlstein notes — Nixon appeared to endorse them. Dent was thus the Southern face of Nixon’s two-faced campaign and administration. Time noted in 1969: “Whenever the White House seems to drift to the right or placate Southern interests, Presidential Aide Dent is thought to be deeply involved.” In 1981, Dent, now an evangelical preacher, evinced regret for “anything I did that stood in the way of the rights of black people.”

Stuart Spencer, who ran Reagan’s presidential campaigns in 1980 and 1984, President Ronald Reagan, and Lee Atwater on Air Force One, heading to Alabama on October 15, 1984. Photo source: Reagan Presidential Library.

Lee Atwater was the key Southern Strategist after Dent’s retirement. Atwater first gained prominence by stealing a national College Republican election for his protégé Karl Rove (George H.W. Bush was the final arbiter). An acolyte of Thurmond, Atwater cut his vicious political teeth in South Carolina in the 1970s, where he claimed a Republican could only win by using personal attacks. He perfected the “snap” poll: a fake poll whose purpose was to impugn an opponent. In 1980, Atwater’s fake pollsters told white suburbanites that congressional opponent Tom Turnipseed was a member of the NAACP. Thurmond sent letters claiming Turnipseed favored disarmament, and would, as Turnipseed put it, turn the country “over to the liberals and Communists.” Most memorably, Atwater garnered national coverage when he told the press that Turnipseed had been “hooked up to jumper cables” as a “mentally ill” student (Tom Turnipseed, “What Lee Atwater Learned,” Washington Post, April 16, 1991). Antonio D’Ambrosio (“Lee Atwater’s Legacy,” Nation, October 8, 2000), credits Atwater with “some of the worst political smear campaigns in political history.” Colorado representative Pat Schroeder called Atwater “probably the most evil man in America.”

Atwater was an advisor to Ronald Reagan, the campaign manager for George H.W. Bush in 1988, and, before succumbing to brain cancer in 1991 at the age of 40, the chair of the Republican National Committee. Unlike Stephen Miller and Steve Bannon, whose racism has driven Trump’s immigration policies, Atwater was merely an opportunist, not an ideologue. But he always found a way to make racism work for his candidates. In 1979, Atwater changed South Carolina from a caucus into a strategically critical primary, held before Super Tuesday. In 1980, Thurmond, who up to that point had the only vote that mattered in South Carolina, endorsed a fellow Southerner, former Texas Governor John Connally, in the Republican primary. It should have been game over. But Atwater, through a particularly ingenious race-baiting trick, was able to pull a rabbit — or a multitude of white ducks — out of his hat and deliver the primary to Reagan. When a group of Black ministers who supported Reagan approached Atwater, he said he had no money and sent them to the Connally campaign. Then he spread the rumor that the Connally campaign was trying to buy 100,00 Black votes, and he made it seem like the George H.W. Bush campaign was the source of the rumor. This brought the Connally and Bush campaigns into acrimonious conflict. Reagan moved to the right and his landslide victory left him “looking the statesman” (see: Julian E. Zelizer, “How the South Carolina ‘Firewall’ Collapsed,” Slate, February 18, 2016). Without Atwater’s trickery, Connally would likely have carried the South and brought Reagan’s campaign to a screeching halt.

As president, Reagan declared government the enemy, he crushed unions, and his denunciation of “welfare queens” created racial animus to social welfare programs. Reagan initiated today’s wealth disparity by slashing taxes on the rich (and bleeding the less fortunate by imposing taxes on social security and student financial aid). A recent Rand Corporation study documents astonishing income disparity between 1975 and 2018 in granular demographic detail. By comparison, 1945-1975 was a period of shared prosperity. See Time (“The Top 1% of Americans Have Taken $50 Trillion from the Bottom 90%,” September 14, 2020) and New York Magazine (“Study: Inequality Robs $2.5 Trillion From U.S. Workers Every Year,” September 14, 2020).

On July 8, 1981, Atwater, in an interview with Alexander B. Lamis, provided insider insight into the Southern Strategy’s evolution and its connection to racism:

“You start out in 1954 by saying, ‘Nigger, nigger, nigger.’ By 1968 you can’t say ‘nigger’ — that hurts you. Backfires. So you say stuff like ‘forced busing,’ ‘states’ rights’ and all that stuff. You’re getting so abstract now [that] you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is [that] blacks get hurt worse than whites. And subconsciously maybe that is part of it. I’m not saying that. But I’m saying that if it is getting that abstract, and that coded, that we are doing away with the racial problem one way or the other. You follow me — because obviously sitting around saying, ‘We want to cut taxes, we want to cut this,’ is much more abstract than even the busing thing, and a hell of a lot more abstract than ‘Nigger, nigger,’ you know. So any way you look at it, race is coming on the back burner.’”

Atwater was quoted anonymously in Lamis’ book The Two Party South (1984); Lamis reused the quote and identified the now-deceased Atwater in Southern Politics in the 1990s (1999). New York Times columnist Bob Herbert called attention to the quote by citing it several times, beginning in 2005. For a discussion of Atwater’s quote and the complete 42-minute tape recording, see Rick Perlstein, “Exclusive: Lee Atwater’s Infamous 1981 Interview on the Southern Strategy” (Nation, November 13, 2012.)

(The quote transcribed above starts at 16:17.)

Republican National Committee chairman Ken Mehlman gave a tepid apology at an NAACP convention in 2005: “some Republicans” were “wrong” to attempt to “benefit” from “racial polarization.” (Mike Allen, “RNC Chief to Say It Was ‘Wrong’ to Exploit Racial Conflict for Votes,” Washington Post, July 14, 2005). Mehlman added it is not “in the interests of African Americans” to vote 90% Democratic. (Go here for Mehlman’s complete text.) Herbert denounced this apology (“An Empty Apology,” New York Times, July 18, 2005) as “worse than meaningless” because the “decades-long Southern strategy … racist at its core, still lives.” Herbert describes the strategy as feeding “like a starving beast on the resentment of whites… furious about the demise of segregation and other civil rights advances.”

The white migration to the Republican Party was not unforeseen. According to Bill Moyers, a melancholy President Johnson told him the evening he had signed the Civil Right Act of 1964: “I think we just delivered the South to the Republican party for a long time to come.”

Atwater is credited with convincing Ronald Reagan to initiate his 1980 presidential election campaign at the Neshoba County Fair (“famous for its diatribes by segregationist politicians” says Herbert) in Philadelphia, Mississippi, a place made infamous by being the location of the murder of three civil rights workers. The crowd was thrilled when Reagan declared his fealty to “state’s rights,” understood as support for the discriminatory status quo. In an uncanny dog-whistle echo of Reagan, Trump attempted to hold his first post-coronavirus campaign event in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where affluent blacks were massacred in 1921, on Juneteenth — the day enslaved people in Texas learned they were freed. After objections, the date was changed, but there can be little doubt the Trump campaign was trying to convey a coded message through scheduling.

Trump generally prefers to shout his racism from the rooftop (conveniently, McSweeney’s has catalogued Trump’s 889 — and counting — “atrocities,” commencing with his anti-Obama birtherism) rather than camouflage it in code. Even when Trump extols his “good genes,” it’s not really a dog whistle. Nonetheless, Politico noted on July 12, 2020 that Trump and his administration signaled support of QAnon conspiracies by frequently retweeting content. When asked directly about QAnon in August, Trump pretended not to know much about the “deep-state,” pedophile/cannibalism conspiracy theory that views him as the savior of the Western world, but he approved of the group’s approval of him (Kevin Liptak, “Trump embraces QAnon conspiracy because ‘they like me,’” CNN, August 19, 2020). QAnon adherents likely take this as a bold affirmation, cautiously expressed, so as not to forewarn the deep state before Trump crushes it. A Daily Kos/Civiqs poll conducted between August 29 and September 1 found most Republicans believe QAnon “is mostly or partly true.”

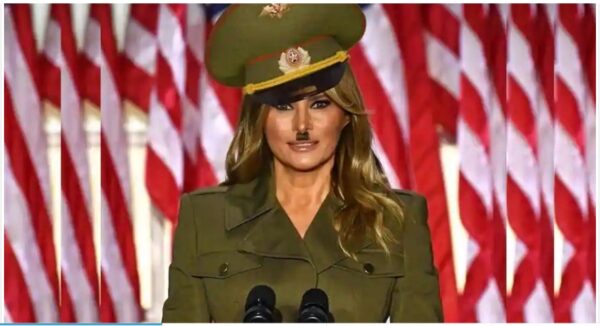

Melania Trump at the Republican National Convention. Jacket by Alexander McQueen. Soviet hat (misidentified by Hindustan Times as German) and Hitler moustache by Diet Prada. Source: Diet Prada Instagram, reproduced in Hindustan Times.

Melania Trump’s “dictator-chic” attire during her Republican National Convention speech constitutes dog-whistle couture. Recall also that on her flights to and from an immigration detention center in Texas in 2018, she wore a jacket with the slogan “I REALLY DON’T CARE, DO U?” Stephanie Winston Wolkoff, author of Melania and Me, says the First Lady told her the jacket was meant to provoke liberals: “I’m driving liberals crazy… . They deserve it.” Melania was a birther who, according to Winston Wolkoff, echoes her husband’s views of immigrants (go here for a secret recording from 2018), and refused to move to the White House until the toilets and showers used by the Obamas were replaced.

For QAnoners, Melania’s military-style outfit, worn on the White House grounds, portends the “Storm,” when Trump renders Democrats, movie stars, and other child-molesting perverts to Guantanamo Bay. To Hawaiian-shirted militia, it signals the “Boogaloo,” the coming Civil War. This battle-ready “fascion” — as Diet Prada (the savvy, politically correct fashion police on Instagram) dubbed it — caters to a host of unhinged authoritarian fantasies held by Trump-supporting makeshift militias wherever they may be found. See Alfea Jamal, “Melania Trump or Adolf Hitler? Diet Prada calls FLOTUS out…,” Hindustan Times, August 27, 2020. Melania anchored her uniform with pointy stilettos. For me, this fashion choice invokes Rosa Klebb, the cruel and remorseless Soviet/SPECTRE agent who attacked James Bond with her poisoned, spike-tipped shoe in the film From Russia with Love (1963).

More Monkey Business: Atwater’s Deathbed Confession

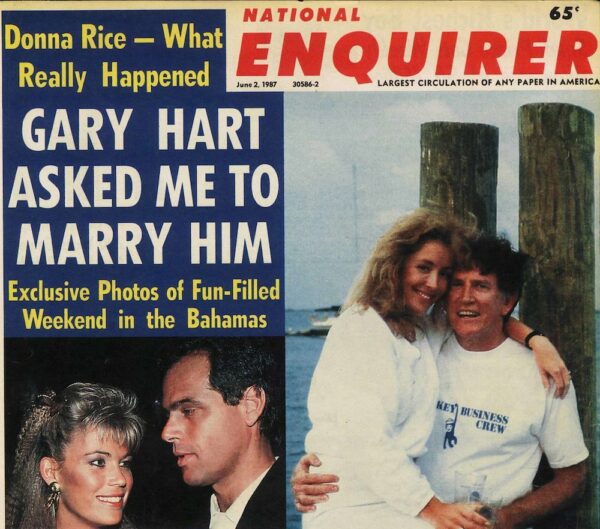

National Inquirer cover, June 2, 1987. Former Senator Gary Hart (with Monkey Business Crew shirt) and Donna Rice at dock in Bimini, around March 1, 1987. Lawyer and lobbyist Billy Broadhurst invited Hart, Rice, and Lynn Armandt on a yacht trip. Monkey Business was subbed for another yacht. Hart says Armandt directed Rice to sit on his lap and snapped the picture instantaneously. In May, Broadhurst brought the two women to Washington D.C. When Hart and Rice subsequently entered Hart’s townhouse, a Miami Herald reporter was already staking it out. The Herald quickly fielded a “clownish” five-man stakeout that overwhelmed the small street (Matt Bai, “How Gary Hart’s Downfall Forever Changed American Politics,” New York Times Magazine, September 18, 2014). Jim McGee and Tom Fiedler broke the story on May 3 (“Miami woman linked to Hart candidate denies any impropriety,” Miami Herald). Hart dropped out of the race the next week. Armandt later sold her picture to the National Enquirer.

Atwater is best known for eviscerating Michael Dukakis in 1988, but first he destroyed the presidential ambitions of the Democratic heir apparent, former Senator Gary Hart of Colorado. On his deathbed in 1991, Atwater called Raymond Strother, Hart’s campaign manager, and confessed: “I fixed Hart.” He claimed credit for the “Monkey Business affair,” the revelation of Hart’s presumed extra-marital affair with Susan Rice — a former honors student and Miss South Carolina World beauty queen — that ended the Hart campaign. Though Hart and Rice said their relationship was not sexual, their denials met with widespread disbelief. Hart says he would otherwise have won the 1988 election. (See: James Fallows, “Was Gary Hart Set Up?,” The Atlantic, November 2018.)

With a Hart presidency — or any democratic presidency — Reagan, Bush, and others would have been prosecuted for their role in Iran-Contra (see my Enriqe Chagoya II article in Glasstire), and those who were charged or convicted would not have been pardoned, as they were on the advice of William Barr. Joe Conason calls Iran-Contra “one of the biggest scandals in American history,” and Atwater is credited with helping Bush avoid culpability. Hart was an outspoken critic of it. The absence of a Bush I presidency and the taint of Iran-Contra would preclude a Bush family dynasty. Additionally, Clinton would not have been elected in 1992. Republican insiders say Atwater had an early appreciation of Bill Clinton’s potential, and that Atwater would have destroyed his political career. Atwater initiated attempts to smear Clinton when he was running for reelection as governor of Arkansas, but never finished the job (see the documentary Boogie Man: the Lee Atwater Story, directed by Stefan Forbes, 2008).

The Hart-Rudman Commission (and Hart personally) warned of an attack on U.S. soil, and a president who was more alert than Bush II might have prevented the 9/11 attacks. If not, perhaps the negative consequences (Islamaphobia and xenophobia, the Patriot Act, widespread spying on Americans, the use of torture, endless war in Afghanistan, etc.) would not have been as bad. Without Bush II, as Hart told Fallows, there would have been “no Iraq War, no Cheney.” For the calamitous and continuing fallout from the Iraq War, see Chagoya II.

Clinton’s biggest successes were Republican goals: NAFTA, the 1994 Crime Bill, bank and telecom deregulation, welfare reform, and the balanced budget (see Mark Karlin, “Thomas Frank: Bill Clinton’s Five Major Accomplishments Were Longstanding GOP Objectives,” TRUTHOUT, May 15, 2016). Even Clinton wanted to partially privatize social security. Goldwater would have heartily approved of these “abstract” policies. Though Clinton campaigned as a populist, he became a Trojan horse for the Republican agenda. His policies hurt the working class and people of color in a severely disproportionate manner. Had Bill not been president, it is unimaginable that Hillary would have been the Democratic nominee in 2016. Nor would she have been burdened by decades of anti-Clinton vilification that can be traced back to Atwater’s hyper-partisanship. Still, even with a perfect storm of factors that broke his way, Trump’s Electoral College win in 2016 was by slim margins in a few key states. Without just one of Atwater’s dirty tricks (assuming no others took its place), we could be living in a much better world.

Bush, Dukakis, and “Willie” Horton

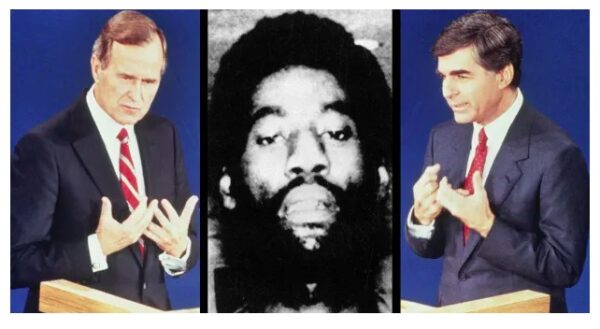

William Horton’s mugshot, framed by images of Bush and Dukakis in a presidential debate, 1988. Atwater famously declared: “By the time we’re finished, they’re going to wonder whether Willie Horton is Dukakis’ running mate.” Photo source: History.com

George H.W. Bush trailed Dukakis in the presidential polls by double digits in 1988 when, on September 21, a PAC unleashed “Weekend Passes,” now known as the “Willie Horton” ad. It was the most influential, race-baiting ad in campaign history. William Horton was a black man serving a life sentence in Massachusetts for robbery-murder (he was convicted with three others). Released on a furlough program in 1987, he did not return and he was convicted of raping a white woman and stabbing her fiancée. (Horton denies all major charges.)

The ad flashed between Horton’s mug shot and images of the two candidates. It noted Bush’s support of the death penalty, and implied that Dukakis would unleash black murderers and rapists. The success of this ad likely influenced Trump to refer to Mexicans as rapists when he launched his 2016 presidential campaign at Trump Tower. An enlarged photograph of Horton, who was renamed “Willie” by Republicans, hung in Bush’s campaign headquarters. Horton disliked and never used the diminutive “Willie.” He thought it was part of a Republican plan to create a stereotypic, threatening “fictional character” that was “big, ugly, dumb, violent, black — ‘Willie.’” This use of the diminutive has been explained as a white man’s “overstated familiarity.” But I see a more sinister, subliminal motivation. Atwater surely was aware that “willy” is a slang word for penis. Therefore, the implication is that Dukakis released Penis Horton, so that he could rape white women. The photograph used in the ad was taken after Horton spent weeks in solitary, recovering from surgeries and a gunshot. “I would have been scared of me, too,” he said of this picture. (For a clip of the ad and a discussion, see Erin Blakemore, “How the Willie Horton Ad Played on Racism and Fear,” History.com, November 2, 2018.)

Atwater acknowledged the Horton case as a “gut” issue, “particularly in the South.” He added: “…if we hammer at these over and over, we are going to win” (Roger Simon, “How a Murderer and Rapist Became the Bush Campaign’s Most Valuable Player,” Baltimore Sun, November 11, 1990).

Bush and Atwater emphasized crime, furloughs, and Horton as a prelude to the ad. Tellingly, the campaign never mentioned any white convicts that used the furlough program to commit crimes. For a short discussion of the ad by several key figures, see “Willie Horton: Political Ads that Changed the Game,” Retro Report, July 24, 2016.

The ad was the turning point in the campaign, and its influence went far beyond the 1988 election (the Clinton crime bill is mentioned above). Susan Estrich, manager of the Dukakis presidential campaign in 1988, observes in the Retro Report clip: “In the wake of that race [Bush-Dukakis], every democratic politician I knew was tripping over themselves to vote for three-strike laws, mandatory sentencing, anything they could vote for to prove they were tough on crime. What [the] Willie Horton [ad] did was create a generation of legislators who voted for everything. And the result was crowded prisons, suspicion in the minority community, tensions that continue to this day.” (Black Lives Matter imagery flashes as she completes her statement.) Beth Schwartzapfel and Bill Keller note a decades-long “frenzy” of “tough-on-crime one-upmanship,” and cite Senator Richard J. Durbin, who notes: “the ghost of Willie Horton has loomed over any conversation about sentencing reform for over 30 years” (“Willie Horton Revisited,” The Marshall Project, May 13, 2015). As Michelle Alexander points out in The New Jim Crow (2010), felons “almost never truly reenter the society they inhabited prior to their conviction.” Michael Bloomberg recently raised $16 million to enable 31,000 Florida felons to have the right to vote. Recall also that Nixon’s “war on drugs,” as noted by John Ehrlichman in Reyes, Part 2, was designed to target Blacks and hippies.

The Horton ad set a precedent for PAC ads that campaigns wouldn’t dare release directly. Atwater — who always publicly denied responsibility for the ad — reveled in the plausible deniability the PAC afforded him. In the film Boogie Man, Roger Stone says Atwater (a sometime partner in the political consulting/lobbying firm Black, Manafort, and Stone) invited him to his office, played the Horton ad, and said he had $2 million to put the ad out “independent” — a violation of campaign finance laws. Stone says he called the ad “racist” and warned that Atwater and Bush would “wear that to your grave.” Stone says Atwater responded: “Y’all a pussy.” Atwater set an example by habitually pushing the limits of the permissible. Stone, of course, is the single individual most responsible for Trump’s presidential candidacy, as noted by NPR. Stone, who was convicted of obstructing justice in the Russia probe, had his 40-month prison sentence commuted by Trump on June 10. Stone had masterminded the “Brooks Brothers Riot” that stopped vote-counting in Florida in the 2000 election. Stone has already told Infowars that Trump should declare martial law and jail the Clintons and others if he loses the 2020 presidential election (“Roger Stone to Donald Trump: bring in martial law if you lose election,” Guardian, September 13, 2020).

In a loose-lipped moment a month before the 1988 election, Roger Ailes, the campaign’s media consultant (and subsequently head of Fox News), told the press: “The only question is whether we depict Willie Horton with a knife in his hands or without it” (Bernard Weinraub, “Campaign Trail; A Beloved Mug Shot for the Bush Forces,” New York Times, October 3, 1988).

After the Horton ad had run for 25 days in limited markets, the Bush campaign hypocritically claimed it was offensive and requested that the ad be retired. Simon says the ad had received so much free news coverage that most Americans could have picked Horton out of a lineup. Other materials with Horton’s photograph were utilized by the campaign. Simon notes a Bush ad that placed Dukakis in a dark environment, subliminally associating him with Horton. In Boogie Man, Dukakis shows a leaflet used in several states that prefigures “Pizzagate” and QAnon. It reads: “All the murderers and rapists and drug pushers and child molesters in Massachusetts vote for Michael Dukakis.”

On October 5, 1988, the day after the Horton ad was pulled, the Bush-Quayle campaign released the “Revolving Door” ad, the knockout punch in a carefully orchestrated campaign. Men entered a high-fenced prison and came right back out through a turnstile gate. Many — including Ishmael Reed and Sam Donaldson in Boogie Man — noted that the Black man with a big Afro is the only one who looks up. This signifies that, of all the prisoners, he is the dangerous one.

In addition, Atwater plotted a host of dirty tricks. In Boogie Man, Robert Novak recalls that Atwater attempted to get him to claim Dukakis had psychiatric problems: “It was really a slander.” Others called for the release of Dukakis’ medical records. When Reagan was queried about them, he replied: “I’m not going to pick on an invalid.” (Perhaps this inspired Trump to call Biden senile, and to attempt to confirm the diagnosis by triggering Biden’s speech impediment by repeatedly interrupting him in the first debate this year.) Though Dukakis’ wife Kitty had never attended a demonstration, rumors were spread that she had burned an American flag at one in the 1960s, and that pictures were “floating around.” It was also implied that Dukakis was against the pledge of allegiance.

Roger Stone cites the Atwater wedge issues that defined the election: the American flag, the pledge of allegiance, and prison furloughs. He queries, with a mix of admiration and incredulity: “Who would buy that? It’s so irrelevant.” Stone also explains why they were employed: “If you let the campaign be about Bush, he probably would have lost. The campaign had to be about the values you project onto Dukakis. It was an early example of the culture war” (as quoted in Boogie Man).

George H.W. Bush was born in Massachusetts and raised in Connecticut, which his banker father Prescott represented in the Senate from 1952 to 1963. H.W. attended Phillips Academy and Yale. Like other Yalie relatives, including his father — and more than a few notable Cold Warriors — H.W. was tapped to join Skull and Bones, the university’s exclusive secret society. (The benefits W. received from Bonesmen are noted below). The Bush family also long maintained a summer retreat in Kennebunkport, Maine. Notwithstanding his transplantation to Texas, H.W. was heir to exalted Yankee-elite bona fides that few politicians could match. Dukakis, by contrast, was the son of Greek immigrants. Yet Atwater successfully portrayed Dukakis as the out-of-touch Eastern elitist, whose campaign “probably sat up in Brookline eating Belgian endives and quiche out of a can.” Candidate Bush, by contrast, dutifully munched on pork rinds — allegedly his favorite food — and flashed his cowboy boots, saying “Don’t let them tell you I’m no Texan. Take a look at that.” Meanwhile, W. told Texans that Dukakis wanted to take away their guns. Atwater transformed how modern campaigns are run, beginning with an opposition research staff of 100 that worked around the clock. His targets included working-class voters. Frank argues that the Democrats largely abandoned the working class after the 1970s to become the party of educated professionals. He is particularly critical of NAFTA, drafted by Republicans “to break the power of organized labor.” Since it was passed by Bill Clinton, Trump won working-class support by using it as a bludgeon against Hillary Clinton in 2016 (see “Frank: Trump won because Clinton and the Democrats dismissed the concerns of working people,” Tranché L’OBS, June 4, 2018).

Black protesters of school board policies and white counter-demonstrators, Memphis, August 31, 1963. Photograph by Bill Hudson, AP. One girl’s sign reads: “Racial Inter-Marriage begins with holding hands in the first grade.” Another girl’s sign says: “The Lord made us distinct races for a reason.” One man’s sign reads: “Elect white men with white hearts.”

Eric Alterman, in Boogie Man, explains this transformation: “The Republican Party has turned into a stealth party that argues on behalf of the common man and gives all the benefits to the wealthiest one-tenth of one percent. It argues on behalf of certain morality policies, [and] engages in completely different private behavior.” As a far-right party devoted to corporations and the rich, the Republicans had to capture other voting blocks to achieve electoral success. Nixon had already claimed he represented the “silent majority.”

Jingoists and racists were easy Republican pickings, but they weren’t sufficient. Gun rights and abortion became primary Republican planks because they snagged vital single-issue voters, who could largely be appeased by rhetoric and Supreme Court appointments. Abortion — initially viewed as a Catholic issue — did not emerge until six years after the 1973 Roe v Wade decision because many evangelical leaders and Republican politicians actually supported abortion. Randall Balmer argues in Politico (“The Real Origins of the Religious Right,” May 27, 2014) that when evangelicals organized against fellow evangelical Jimmy Carter in 1979, abortion was a cover for their real concern, which was tax-exempt status for racially-segregated private schools. Alterman adds that Atwater privately mocked anti-abortion stalwarts, describing them as mutant freaks: “the ‘extra chromosome group’ and the ones who had a hand coming out of their head, or a third eye.”

Dukakis, who wanted to campaign on his issues, largely refused to respond personally to Atwater’s attacks. Donaldson expressed amazement that Dukakis never pointed out that the Massachusetts furlough program was modeled on Reagan’s in California. Reagan had defended his program, even when two of his furloughees committed murders. All states had furlough programs of some kind, and the one in Massachusetts have been initiated by Republican Governor Francis W. Sargent. Atwater demonstrated the efficacy of attack campaigns: to ignore them is to lose. Moreover, anyone who thereafter appeared “soft” on crime could be “Willie Hortoned.” Alterman termed race “a poison” that works for Republicans because “people vote their fears and not their hopes.”

Atwater’s brinksmanship won him the chair of the RNC, inaugurating what Conason calls a “ruthless, win-at-any-cost Republicanism.” W. Bush studied the master at close range because he was assigned to accompany the untrustworthy, backstabbing manager during H.W.’s presidential campaign. W. had lost a congressional election in 1978, which he partially attributed to conspiracy theories relating to his elitist heritage, which he denounced as “connect-the-random-dots charges that are virtually impossible to refute.” Unlike QAnon, some of these connections, and elite organizations like the Trilateral Commission, actually did exist. W. was probably admitted to Yale through the influence of Bonesmen. He also earned a degree from the Harvard Business School. When he was rejected by the UT Law School, a Bonesman gave him his first job. Bonesmen invested in his energy company and contributed to his gubernatorial and presidential campaigns. With the benefit of Atwater’s political schooling, W. rode his Texas persona all the way to the White House (see Alexandra Robbins, “George W., Knight of Eulogia,” The Atlantic, May, 2000). Despite a short life, Atwater cast a very long political shadow.

W. eschewed the rather transparent racism that Atwater used in his father’s presidential campaign. I agree with those who hold that W. perfected a dog whistle that was all-but-inaudible to the uninitiated. When he condemned the Dredd Scott decision (the fugitive slave ruling of 1857), W. was signaling opposition to Roe v. Wade. His use of phrases from hymns and scripture were also coded messages to believers who habitually searched for occult, hidden meanings (see David D. Kirkpatrick, “Speaking in the Tongue of Evangelicals,” New York Times, October 17, 2004).

Shortly before the strategically important South Carolina primary, W. spoke at Bob Jones University in Greenville on February 2, 2000. It was a highly symbolic act because the school had been at the center of the conflict over tax-exempt status for segregated schools noted above. In 1982, the Reagan administration was going to side with Bob Jones University in the Supreme Court, but it retreated after that position met with widespread disapproval. In 1983, the court ruled against the university 8-to-1. The dissenter was William Rehnquist, who Reagan elevated to Chief Justice in 1986. Eventually, Bob Jones grudgingly admitted some Blacks, but it was still prohibiting interracial dating in 2000, when W. spoke. After encountering negative publicity, W. quickly and publicly distanced himself from the university’s racism and anti-Catholicism (see Greenville News, March 11, 2017). While Reagan and W. courted Southern racists, they also responded to public opinion.

Bush presumably approved Mehlman’s 2005 Republican Party apology noted above. Herbert points out that W’s supporters, particularly his brother, Florida Governor Jeb Bush, “have gone out of their way to prevent or discourage blacks from voting.” Jack Bass argues that W.’s appointment of federal judges hostile to Civil Rights continues the Southern Strategy (“That old-time ‘Southern strategy,’” Salon, March 25, 2004; also see Charlie Savage, “Appeals Courts Pushed to Right by Bush Appointees,” New York Times, October 28, 2008).

W.’s most far-reaching appointment was that of Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts in 2006. Roberts had advised Jeb Bush and Republican strategists during the fateful 2000 presidential election that was decided by Bush v. Gore (which caused Gore to concede). Well known for his longstanding hostility to voting rights, Roberts wrote the 5-to-4 opinion in 2013 that gutted the 1965 Voting Rights Act. His hostility to voting rights continues (Emmett Witkovsky-Eldred and Nina Totenberg, “As Concerns About Voting Build, The Supreme Court Refused to Step In,” NPR, July 25, 2020). W. paid back Roberts’ election assistance in the 2000 election by elevating him to the Supreme Court. Trump, meanwhile, has nominated Amy Comey Barrett to energize his base and possibly to help award the presidency to him after the 2020 election.

There is no recent parallel to Trump’s overt hostility to Latinos. Check out the April 4, 1980 debate between H.W. Bush and Reagan. When asked about undocumented immigrants, they fall over themselves trying to say good things. H.W. Bush declares: “These are good people, strong people. Part of my family is Mexican.” Reagan says: “Rather than… putting up a fence, why don’t we… open the border both ways… .” Latinos are a very heterogeneous group. They include: activists who consider themselves people of color, fiscal liberals who are religiously and socially conservative, and even white supremacists (more on the latter below). This means a certain number of votes are always winnable.

W. Bush very successfully courted the Latino vote, winning 35% in 2000 and 40% in 2004. Republicans, cognizant that they are a shrinking minority, briefly pivoted to a more Latino-friendly platform, but retreated when the Republican base revolted. In any case, support does not always reflect platform. Bill Clinton pulled 72% of the Latino vote in 1996, when he was “more of a border hawk than Dole” (Julio Ricardo Varela, “The Latino Vote in Presidential Races: 1980-2012,” Latino USA, October 29, 2015). Obama also fared very well with Latinos, even though he was dubbed the “deporter-in-chief” when he ran for reelection in 2012. Unauthorized immigration through Mexico continued to decline during Obama’s presidency, as did border apprehensions, though removals (but not returns) increased substantially (see Muzaffar Chishti, Sarah Pierce, and Jessica Bolter, “The Obama Record on Deportations: Deporter in Chief or Not?,” Migration Polity Institute, January 26, 2017). Trump’s build-the-wall fantasies were never realistic. Moreover, they found fanatic support during a period of low immigration. This means they are a function of white fear of current and future demographic change (see “The Fractured Politics of a Browning America,” Vox, August 23, 2018).

Trump and the Southern Strategy

The “classical” Southern Strategy featured Southsplainers (surrogate mouthpieces) and codes. Trump, however, has no use for other mouths (even Stone was pushed aside when he grew too prominent) or subtlety. Trump, in fact, did not want or expect to win the presidency. We now know that this bold exercise in racist branding and white resentment was driven by economic duress (Chris Cillizza, “Donald Trump’s taxes reveal why he ‘really’ ran for president,” CNN, September 28, 2020). Nonetheless, The Donald triumphed, initially to the consternation of the Republican Party establishment. But the party has now devolved into a Trump cult, to the extent that the 2020 campaign does not even have a platform. The Democratic platform, of course, is woefully inadequate for our historical moment, but that is nothing new.

Additionally, the political climate has been transformed by the Black Lives Matter movement, the massacre of Black worshippers in a Charleston church in 2015, and the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in 2017. Confederate flags, statues, and generals are finally recognized as emblems of white supremacy, even by state and municipal governments in the former Confederacy, the U.S. military, and NASCAR. Many corporations — and even the NFL — have come around. Consequently, Trump’s embrace of Confederate emblems is, in Atwater’s terms, the 2020 equivalent of yelling “nigger, nigger” in 1968. While Trump’s carpetbagger Confederate patriotism inflames his base, it — like other Trump excesses — backfires with portions of other important constituencies.

For Eugene Robinson, the Confederate flag “represents the knee that has been kept on the necks of African Americans … for 401 years.” If, at last, “the Lost Cause is finally, truly lost,” that renders Trump the last Confederate president (“Donald Trump might go down in history as the last president of the Confederacy,” Washington Post, June 11, 2020). Paul Waldman, who notes growing diversity “literally by the day” views the Trump presidency as the death-knell of the Southern Strategy (“How Donald Trump will finally kill the Southern Strategy,” Washington Post, July 1, 2020). Adam Sewer says the “cruelty of the Trump age” has given rise to what might be the first anti-racist majority in U.S. history. He calls for a new reconstruction in order to realize the promises that have been unfulfilled since this nation’s founding (“The Next Reconstruction,” The Atlantic, October, 2020).

The Hypocrisy of Law-and-Order Presidents