For Part I of this article, which introduces Reyes’ work in the context of the Chicano movement and the Chicano Moratorium and makes parallels with the Black Lives Matter movement, please go here.

This article focuses on the early history of the United Farm Workers, the eagle that serves as its emblem, and on five Reyes paintings that feature United Farm Workers imagery, c. 1970-72, including his landmark reassessment of the Alamo. It also deals tangentially with the Con Safo art group (the subject of a future Glasstire article). Reyes was the prime mover behind this influential art group.

The Chicano movement was galvanized by — and it became deeply identified with — the struggles of the United Farm Workers Union (UFW). Union actions brought together all sectors of society across vast geographical spaces, from the most rural to the most urban, from the impoverished to the prosperous, and from the least educated to the most educated. The UFW was formed by the merger of two predecessor unions. The National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) was led by César Chávez and Dolores Huerta; its members were primarily of Mexican descent. Larry Itliong led the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), whose members were primarily of Filipino descent. Chávez, who staged dramatic marches and fasts, became the public face of the UFW. He is also responsible for the creation of the UFW eagle, the union emblem used on flags, banners, buttons, placards, and hats. This eagle became the primary symbol of the Chicano movement, and it appears in the five Reyes paintings discussed in this article.

Chávez wanted a distinctive and easily recognizable emblem that could serve a workforce and an anticipated constituency that did not have a high rate of literacy or a common language. Ed Fuentes summarizes the creation of the eagle in “How One Flag Went From Representing Farmworkers to Flying for the Entire Latino Community.” In 1962, Chávez’s brother Richard and his cousin Manuel created a simplified, semi-abstract eagle inspired by the Aztec eagle. Graphic artist Andrew Zermeño “interpreted the wings as an inverted pyramid” and also tweaked the neck, which too closely resembled that of a turkey. The black eagle was placed within a white circle on a red flag. Simple forms and elemental colors were utilized so that non-artists could easily replicate them with readily available supplies.

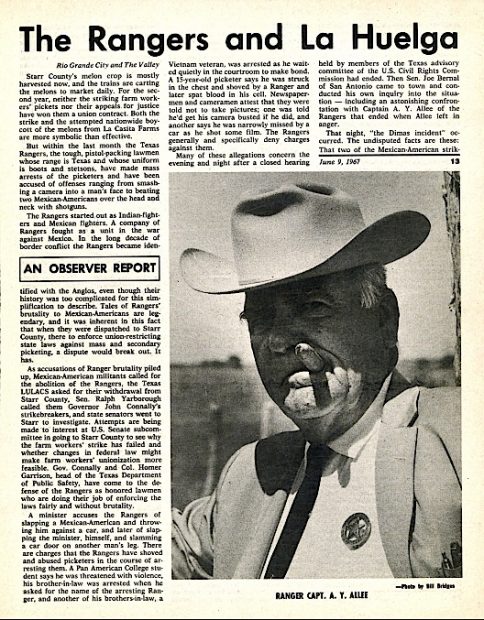

César Chávez, First Grape Strike by National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), January 3, 1966 (detail). Photograph by George Ballis.

The topmost eagle in this photograph appears to be one of the “turkey neck” variety.

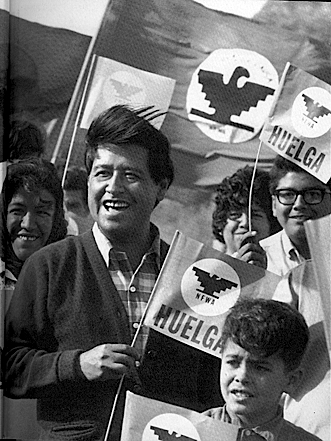

Andrew (Andy) Zermeño (b. 1935), United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, Huelga (Strike), 1966, offset lithograph, 24 x 18 ½ inches.

Zermeño remedied the turkey-necked eagle by creating a thick neck that was separated from its wings by a jagged, lightning-like white line. His bold and stylish modification can be seen three times in his Huelga lithograph.

The UFW had been winning contracts in California since 1966, mostly with small growers. It achieved its most significant victory in July of 1970, when many growers, including the largest producer of table grapes, signed agreements with the union. The California grape strike was initiated by AWOC in 1965. Chávez had not thought the time was ripe for a strike, but he joined the strike at AWOC’s request. The two unions merged to become the UFW, which affiliated with the AFL-CIO. United Auto Workers Union President Walter Reuther met with Chávez and Itliong, and also provided financial resources and experienced organizers and negotiators.

The Senate subcommittee on Migratory Labor held hearings in Delano, California in 1966, where Senator Robert F. Kennedy chastised the Kernn County Sheriff for arresting lawful strikers because growers had threatened them. Kennedy directed him and the district attorney to read the Constitution. (Click here for Youtube clip.) Chávez, who utilized religious iconography, including the Virgin of Guadalupe, led a 340-mile march from union headquarters in Delano to the state capital in Sacramento in 1966, which he characterized as a peregrinación (pilgrimage). Farm workers had been beaten; they were sometimes doused with pesticides by crop dusters, and live ammunition was sometimes fired over their heads in efforts to intimidate them. Some farm workers wanted to respond violently. In order to underscore his commitment to nonviolence, Chávez undertook a 25-day fast in 1968. The breaking of his fast in March culminated in a Catholic mass attended by thousands, including Senator Kennedy. (For a chronology of the UFW, go here.)

Boycotts became a key component of the UFW struggle: while farm workers were excluded from collective bargaining rights under the National Labor Relations Act, they were exempted from subsequent national legislation that forbade secondary boycotts (such as picketing and boycotting stores that sold non-union grapes). These boycotts, which emphasized action in urban centers in the U.S. and Canada, found support among union workers, students, religions communities, and supporters of civil rights. Organizers also effectively lobbied individual store managers. The success of these efforts led grape growers to pivot to European markets. UFW officials parried this strategy by enlisting the aid of powerful European dockworker unions. Though U.S. labor laws barred domestic transport unions (which had collective bargaining rights) from assisting with the UFW boycott, the growers were powerless against European unions. When their grapes rotted on European docks, the growers were forced to sign collective bargaining agreements. The UFW became a successful popular movement through its ingenious navigation of U.S. legal prohibitions and exemptions, and by the speedy and adroit alliances it made with European unions. The UFW took the fight to the big cities, and after they won there, they took the fight to Europe, where they won again. For an online narrative history of the UFW that outlines boycotting strategies, see: Matt Garcia, “César Chávez and the Farm Worker’s Movement,” Oxford Research Encyclopedias (2016).

The UFW eagle was widely reproduced and displayed by supporters of the cause. Fuentes notes that Chávez thought the emblem, through its Aztec roots, expressed “pride” and “dignity” and served as a “strong, beautiful sign of hope.” Fuentes describes the migrations of the UFW eagle: “The flag moved out of rural staging areas to the urban centers of the West like a Mexican meme. The eagle’s head faces to the right, looking to the future. Under wings that mirror the architecture of Mesoamerican temples, the image is anchored in the past, and the base replaces talons, giving it a peaceful stability.”

Before long, the eagle did double duty by becoming the symbol of the Chicano movement itself. We can make a parallel to Black Lives Matter (BLM), which began as a hashtag after Trayvon Martin’s murderer was acquitted in 2013. BLM quickly became a rallying cry against police brutality directed against Blacks, and it is now a broad national and international anti-racism movement. See Leah Asmelash, “How Black Lives Matter went from a hashtag to a global rallying cry,” CNN, July 26, 2020.

As Cesar Martinez, a Con Safo group member (1972-74) notes: “All of us who were politically aware had the image that we knew as the ‘huelga [strike] eagle’ etched in our mind as the symbol that was the most obvious representation of the Chicano political struggle.” This eagle was found in barrios everywhere — and sometimes outside of barrios as well, such as on the Alamo Cenotaph (pictured below).

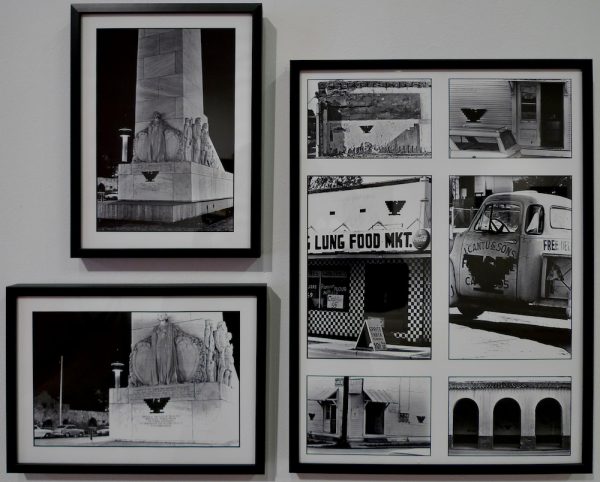

Cesar Martinez (b. 1944), photographs of the UFW Eagle in San Antonio, including on the Alamo Cenotaph, 1972, installation shot from “The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth,” Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, San Antonio, 2018. Photograph by Ruben C. Cordova.

The UFW flag appears prominently in Antonio Bernal’s Del Rey Mural, which is regarded as the first Chicano mural.

Antonio Bernal, Del Rey Mural, 1968, house paint on wood, El Teatro Campesino office wall, 6′ x 15’ (one of two adjacent panels) Del Rey, CA. Photograph by Robert Somer, Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC).

The UFW flag is held by Chávez, who stands between Mexican revolutionaries (who establish a chain of succession) and other activists of color in the U.S.: Reies López Tijerina (he led the land grant movement that contested land ownership in New Mexico), a Black Panther (sometimes interpreted as a combination of a Panther and Malcolm X), and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Con Safo group photograph, summer 1972. Left to right: Santos Martínez, Jesse Almazán, Carlos Espinosa, Roberto Ríos, Felipe Reyes, Jose Esquivel, Vicente Velasquez, Mel Casas, and Jose Garza. Photographer unknown. Reproduction courtesy of Mel Casas Collection, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

When Reyes made the paintings discussed in this article, Chicano painting was a relatively new phenomenon. Moreover, he was not familiar with the art that was being created in California and other centers of Chicano art. Reyes and other San Antonio-based Chicano artists used the same source material, but they devised their own pictorial forms, often derived from their unique Texan experiences. The Con Safo group functioned as a collective laboratory. It provided a forum to discuss, imagine, and create Chicano art in the absence of readily available models and prototypes.

The alternative exhibition venues that were willing to show these explicitly oppositional works did not have significant assets or professional standards and practices, and, as a consequence, many art works that were loaned to them were lost or destroyed. When I met Reyes in 1999, he was not certain that any of the paintings from his Con Safo group period survived (he began his MFA at the University of Michigan in the Fall of 1973 and did not rejoin the group after earning his degree). Even today, Reyes can only account for the survival of two paintings from his time in the group.

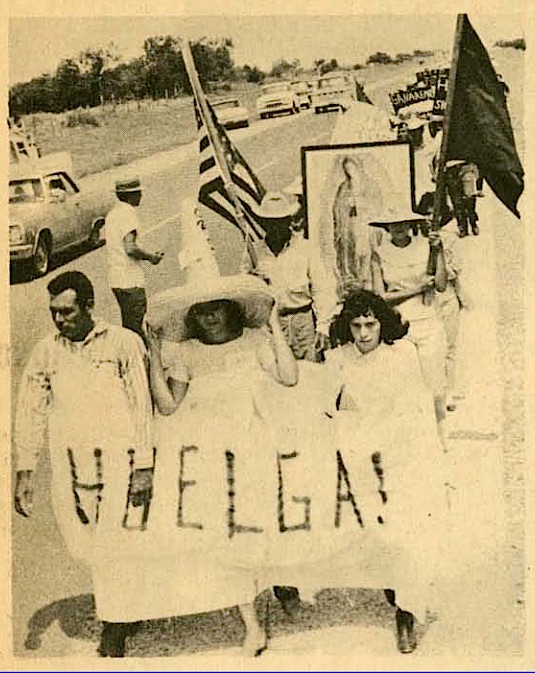

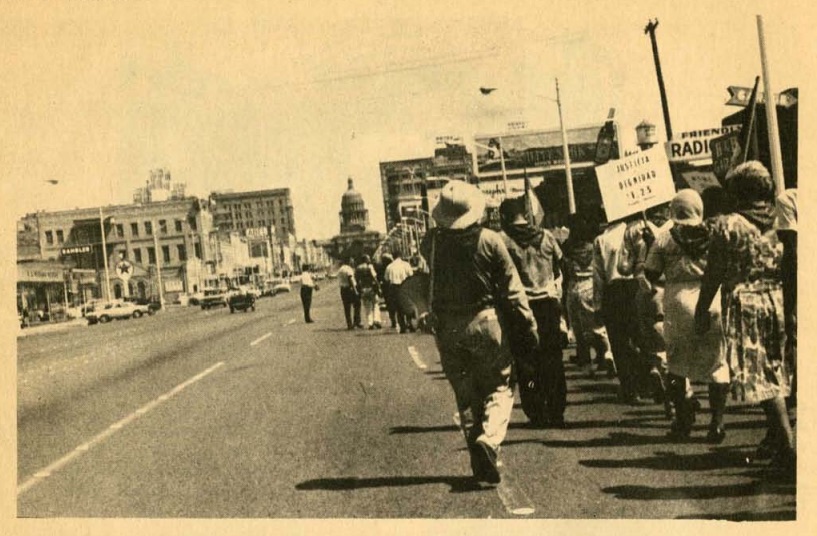

Starr County melon strikers on the way to Austin, marching by the highway, 1966. Source: David M. Fishlow, ed., Sons of Zapata: A Brief Photographic History of the Farm Workers Strike in Texas, UFW, 1967.

Though the California grape strike culminated in resounding success in 1970, the 1966-67 melon strike in Starr County, Texas met with defeat, particularly in the short term, because they only secured one small contract. Farm labor, which generally paid between 40 and 85 cents an hour, was almost the only available work in Starr County. Situated on the Mexican border, it was one of the poorest areas in the state and the nation. Workers had to perform migrant labor in other parts of the country in order to survive. Organizers traveled to Texas, where Eugene Nelson, who had been a picket leader in Delano, established the Independent Workers Association (IWA), which affiliated with Chávez’s NFWA. Seeking $1.25 an hour (the proposed state minimum wage) and collective bargaining rights, they initiated a strike on June 1. Growers rebuffed these terms. No contracts had been signed when the melon harvest ended in June, so a three-to-four day march was planned for July 4. This action that was extended to became a 490-mile, Chávez-like peregrinación from Rio Grande City all the way to the state capital in Austin.

UFW marchers arrive in Austin, Labor Day, 1966. Source: David M. Fishlow, ed., Sons of Zapata: A Brief Photographic History of the Farm Workers Strike in Texas, UFW, 1967.

The marchers included religious leaders, members of other unions, and supporters from all walks of life. Senator Ralph Yarborough joined them briefly in San Antonio, where Robert E. Lucy, Archbishop of San Antonio, called $1.25 an hour “a ghastly recompense for exhausting labor under the burning sun of Texas.” 10,000 or more marched into Austin on Labor Day.

After the march, union activity resumed full force. On October 24, 1966, union organizers blocked the international bridge at Roma because immigration officials had colluded with growers to allow Mexican residents to break the strike. They illegally issued green cards (intended only for U.S. residents) to commuting strikebreakers, who were referred to as “green carders.”

Texas labor laws were extremely repressive and explicitly anti-labor, and courts would subsequently strike a number of them down on constitutional grounds. Texas authorities interpreted these laws liberally and enforced them brutally. Agricultural strike actions that had become conventional in other parts of the country, such as mass picketing and secondary boycotts, were explicitly forbidden under Texas law. The growers were effectively the law in this region. Starr County officials had sprayed oil-based insecticide directly on strikers in San Juan Plaza, Rio Grande City in June of 1966, literalizing Reyes’ Instant Genocide painting discussed in Part 1 of this series. County Prosecutor Randall Nye, who played a part in summoning the Texas Rangers, served as a lawyer for Starr Farms. Many new deputies were created in early 1967. In a subsequent Senate subcommittee testimony, it transpired that three deputies worked for La Casita Farms. Dubbed the “General Motors” of growers, it was at the center of the strike. Union activists were harassed and arrested, on grounds that were both legal and illegal at that time. Offenses included praying on the courthouse steps and shouting “Viva la Huelga.” One supporter who arrived after a demonstration had ended was arrested for “unlawful assembly,” though he was the sole unionist present at that time.

On May 11, as the melon harvest began, the Confederation of Mexican Workers (CMW) set up a picket line on the Mexican side of the bridge. This temporarily stopped the green carders. But Mexican officials disbanded the CMW picket on May 13. According to Sons of Zapata: A Brief Photographic History of the Farm Workers Strike in Texas (David M. Fishlow, ed., UFW, 1967), the green carders posed the greatest threat to the strike: “American workers became less willing to leave the fields, since they knew that there were unlimited numbers of Mexicans to break the strike and take their jobs.”

The Texas Rangers and Alee et al v. Medrano et al.

As noted in Part 1, the Texas Rangers, which were under the legal command of Texas Governor John Connally, intervened in the strike on the side of the growers. The Rangers were habitually deployed as a mobile militia against people of color. By their own admission, they planned to stay until the strike was broken. Whereas many California grape growers ultimately wanted the UFW label (so they could sell in Europe), Texas growers were determined to break the union at all costs. Senator Yarborough declared that the Rangers had been turned into “John Connally’s strikebreakers” (San Antonio Express, May 29, 1967). This phrase was used as the title for the chapter on the Starr County strike in the 1979 book Gunpowder Justice: A Reassessment of the Texas Rangers by Julian Somora, Joe Bernal, and Albert Peña. Texas State Senator Joe Bernal had a heated exchange with Ranger Captain A. Y. Allee on June 1. Later that evening, Bernal declared that the Rangers were “the Mexican Americans’ Ku Klux Klan. All they need is a white hood with ‘Rinches’ [the term Chicanos used to reference the Rangers] written across it” (Texas Observer, “Conversations with the Captain,” June 9, 1967). According to the Observer, Allee had departed his meeting with Bernal “in a blaze of anger.”

That same evening, Allee and other Rangers arrested union activists Magdaleno Dimas and Benito Rodríguez, both of whom sustained multiple injuries. As noted in Part 1, Alee denied that he had tried to kill Dimas. Allee subsequently testified in a federal court that he struck Dimas once in the head with his shotgun barrel. He claimed the other injuries were sustained when Dimas and Rodríguez ran into a door and into each other.

Samora, Bernal, and Peña attribute the strike’s collapse to several factors: a high rate of arrests and fines; rising farm work wages; intimidation; competition from green carder scabs; blame placed on unionists for violence and sabotage. On June 28, State District Judge C. W. Laughlin’s temporary injunction that prohibited picketing at La Casita Farms brought the strike to an end. On July 10, Immigration issued a ruling that prohibited recruiting foreigners to break a certified strike. But the harvest was complete and the strike was already broken.

Senate Subcommittee on Migratory Labor, seated left to right are Senators Paul Fannin (AZ), Harrison Williams (NJ), Ted Kennedy (MA), Ralph Yarborough (TX), Edinburg, Texas, June 30, 1967. Source: David M. Fishlow, ed., Sons of Zapata: A Brief Photographic History of the Farm Workers Strike in Texas, UFW, 1967.

The Senate Subcommittee on Migratory Labor decided to investigate the circumstances of the strike in Starr County. On June 29 and 30, senators listened to testimony in Rio Grande City and Edinburg. Senator Williams, the subcommittee chair, deemed it “the most powerful testimony this subcommittee has ever received as to the need for extending National Labor Relations Act coverage to farm workers.”

Chávez thought the strike had been premature, and that there could be little hope of future success under the prevailing conditions. Consequently, the UFW struggle left the fields and entered the courts. A class action suit was filed in state court in 1967. In 1972, a three-judge federal court ruled on Medrano v. Allee. It struck down five Texas statutes that the Rangers and other law enforcement agencies had used against the strikers. These included prohibitions against mass picketing and secondary boycotts. This decision was affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in Alee et al v. Medrano et al in 1974. (It can be accessed here.)

Justice William O. Douglas wrote the majority opinion. This is part of his summary of the case: “It alleges that the defendants, members of the Texas Rangers and the Starr County, Texas, Sheriff’s Department, and a Justice of the Peace in Starr County, conspired to deprive appellees of their rights under the First and Fourteenth Amendments, by unlawfully arresting, detaining, and confining them without due process and without legal justification, and by unlawfully threatening, harassing, coercing, and physically assaulting them to prevent their exercise of the rights of free speech and assembly. A three-judge court was convened which declared five Texas statutes unconstitutional and enjoined their enforcement.”

This is part of Douglas’ opinion: “The appellees sought to do no more than organize a lawful union to better the situation of one of the most economically oppressed classes of workers in the country. Because of the intimidation by state authorities, their lawful effort was crushed. The workers, and their leaders and organizers were placed in fear of exercising their constitutionally protected rights of free expression, assembly, and association.”

The UFW and the Chicano Movement

The 1966-67 Starr County melon strike resulted in significant legal consequences, though the legal challenge took seven years to conclude. Perhaps more importantly, it had the immediate effect of activating the Chicano movement in South Texas. As David Montejano notes in Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986 (1987): “it ignited a broad resentment among all classes of the Mexican American community. Different agendas and energies were set off, some moderate, some militant. The high school youth boycotted their schools… . College students organized countless protest marches and meetings and provided new ideas and direction as well as energy and impatience. Even the usually proper middle class became radicalized, as they protested employment practices, boycotted companies (at one meeting they burned their Humble Oil credit cards), and filed lawsuits against local companies.”

UFW imagery — as it did everywhere else in the Chicano orbit — figured prominently in San Antonio. Additionally, a UFW representative proposed a national touring exhibition at the Con Safo meeting held on April 6, 1972. A Farm Workers exhibition was held at Trinity University in November of 1972. It was expected to tour nationally and internationally, and ultimately to be shown at the UFW’s national headquarters in La Paz, California. But it came to an ignominious end at its next stop, the UFW office in Mission, Texas. A conflict reportedly broke out between local and national UFW leaders, and the art — without the authorization of the artists — was sold off, allegedly for five dollars a piece. (Hopefully, the owners of works acquired in this manner will make amends with the artists.)

On the heels of its grape boycott triumph of 1970, the UFW initiated a massive lettuce strike and boycott. The Raza Unida Party also celebrated significant victories in Texas in 1970 when it won elections in Crystal City and Zavala County. That a disempowered majority could experience electoral success was a source of great consternation to the Anglo American establishment. It caused Texas Governor Ralph Briscoe to denounce Zavala County as “Little Cuba.”

Reyes made politically charged paintings during this heady period of Chicano movement activism and optimism, when, in the aftermath of recent victories, ambitious new initiatives were being launched.

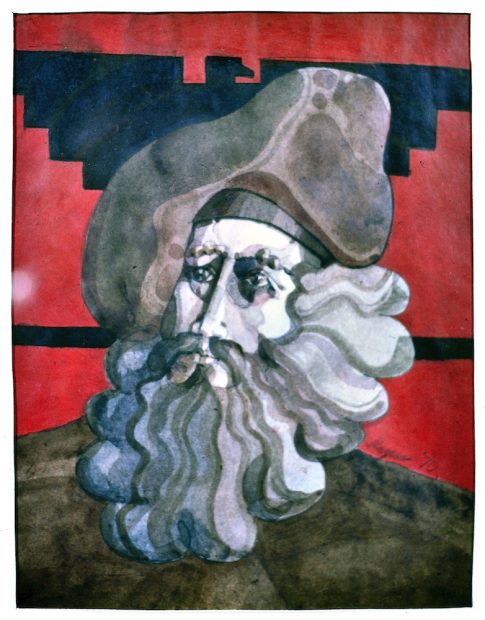

Felipe Reyes (b. 1944), Southwesterly Winds, signed 1970, watercolor and gouache on paper, dimensions unknown, location unknown. Photograph and reproduction courtesy of Cesar Martinez.

Southwesterly Winds was painted during the heyday of hippies and “free love” to reflect changing social trends. In conversations during the early 2000s, Reyes explained that he expected changing mores and social phenomena to lead to a more open and egalitarian society. This painting was intended to “target the Bible belt in particular,” due to the religious right’s distaste for — and intolerance of — long hair. Ironically, conventional images of Christ almost invariably depicted him with long hair and a beard, similar to the fashions sported by many Euro-American hippies at the time.

The contemporary youth movement opposed social, political, and religious mores. Long hair signified defiance of social norms and support for social change. Reyes welcomed what he called the “age of the hippie.” Hippies, in turn, supported the UFW, which is why its colors and eagle form the background for this emblematic picture of social phenomena.

The social revolution did not progress the way Reyes — and many others — had hoped it would progress. It was thwarted by Nixon’s and Reagan’s two-term presidencies, both predicated on “law-and-order” platforms. According to Dan Baum, Nixon’s former domestic policy chief, John Ehrlichman, explained to him in 1996 how Nixon targeted two groups:

“The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left [in which hippies were prominent] and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.” (“Legalize It All,” Harper’s, April, 2016.)

Largely as a consequence of the “war on drugs,” Baum points out, “one of every eight black men has been disenfranchised because of a felony conviction.”

Olivia B. Waxman traces modern law-and-order initiatives beyond Nixon, back to President Johnson and his 1965 declaration of a “War on Crime.” (“Trump Declared Himself the ‘President of Law and Order.’ Here’s What People Get Wrong About the Origins of That Idea,” Time, June 2, 2020). Ed Kilgore, in “Trump is reviving the Disgraceful Legacy of ‘Law-and-order Politics” (New York, June 3 2020), takes a broad historical view of law-and-order campaigns and policies, emphasizing their racist nature. He also explains why it will be hard for President Trump to win reelection with the law-and-order mantle in the 2020 election.

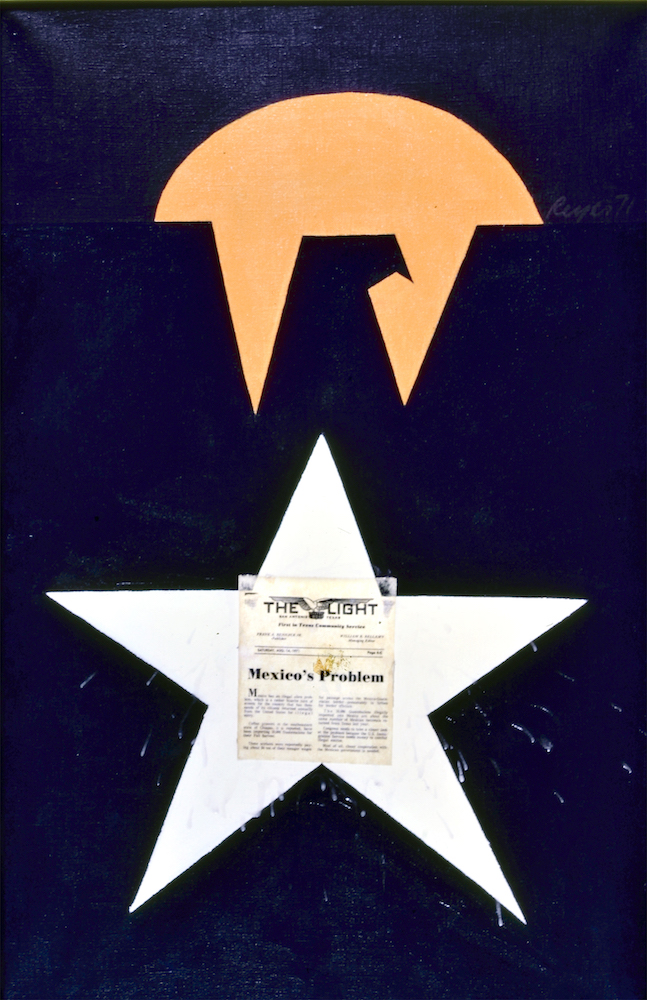

Felipe Reyes (b. 1944), Todos Son Carnales (We Are all Brothers), 1971, acrylic on canvas, with wheat-pasted newspaper article, 36 x 24 inches, location unknown. Photograph and reproduction courtesy of Cesar Martinez.

Todos Son Carnales is Reyes’ most graphically accomplished artwork. It makes remarkable use of negative space by deploying two geometric shapes on a blue-black field. One is a large white star. It represents Texas, the “Lone Star State.” The left side of the state flag has a single white star on a vertical, dark blue rectangular field. The other geometric form is a gold semi-circle, from which two fang-like projections descend. With great economy, Reyes has rendered a black UFW eagle against a gold sun. (Judging by this reproduction, the area that denotes the eagle’s head and wings is darker than the rest of the field.) By virtue of its higher position, the latter form can be interpreted as superior to, or triumphant over the star (Texas). Or, at the very least, the star is making room for the UFW eagle — thus it is finally accommodating Chicanos, the mixed-race descendants of the first peoples (Native American and Spanish) to settle in Texas. In political terms, this iconography anticipates the success of the UFW/Chicano movement in Texas.

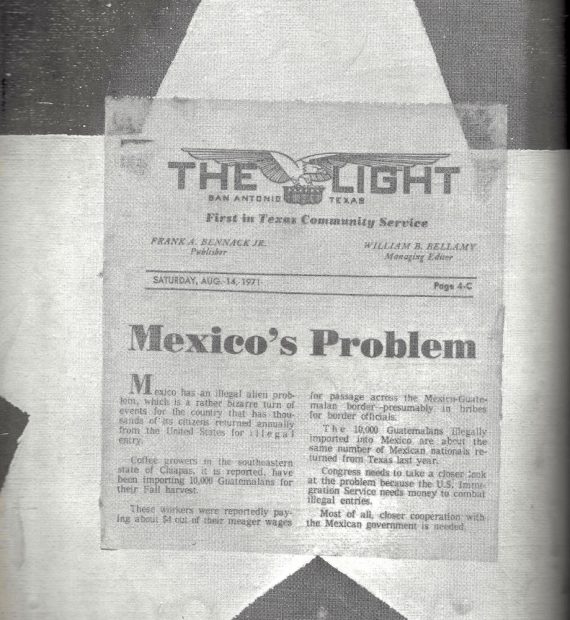

Felipe Reyes (b. 1944), Todos Son Carnales (We Are all Brothers), 1971, detail of wheat-pasted newspaper article. Photograph by Cesar Martinez, as reproduced in Magazín, April, 1972.

Reyes transformed this starkly geometrical painting to make it serve as a vehicle for a newspaper article titled “Mexico’s Problem.” He wheat pasted it — with very deliberate and prominent drips — over the white star.

The article appeared on August 14, 1971, in the now-defunct San Antonio Light, a newspaper whose name is somewhat ironic in this context. The article expressed an anti-immigrant perspective. It claimed that, in a “bizarre turn of events,” workers from Guatemala had created an “illegal alien problem” in Mexico. The article also advised congress to closely examine “the problem” because the U.S. Immigration Service “needs money to combat illegal entries.”

In the April, 1972 issue of Magazín, Reyes states: “This is my reaction to an article in the newspaper concerning wetbacks. This is a fabrication of the white man. As far as I am concerned, the wetbacks are our brothers.”

Reyes explained in the early 2000s that he collaged the article over the star because he viewed dominant Texan culture as anti-Mexican/Chicano, as well as opposed to immigration from anywhere in Latin America. The drops of wheat paste stand in stark contrast to simple forms rendered in paint, like drops from abstract expressionist brushstrokes splattered onto a minimalist painting.

Todos son Carnales, Reyes told me in the early 2000s, “opposes all anti-immigration measures and attitudes, and expresses solidarity with all of Latin America.” In recent conversations, Reyes emphasized how the Trump presidency has made immigration “particularly topical.” Trump launched his campaign at Trump Tower by denouncing Mexicans as rapists, and “he has not ceased his attack on immigrants,” says Reyes, who also notes “Trump has singled out Latinos and Muslims in particular.”

As a native Texan, Reyes has never harbored any illusions about U.S. border agents, and he has been “alarmed” by their increasing militarization, especially after 9/11. Greg Grandin, writing in The Intercept on January 12, 2019, describes the Border Patrol as “a frontline instrument of race vigilantism” that “beat, shot, and hung [Mexican] migrants with regularity.” Torture, rape, and family separation were not uncommon practices. These agents, says Grandin, “wielded awesome power over desperate people with little effective recourse.” Grandin cites John Crewdson, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1980 for detailing abuses, including how the Immigration and Naturalization Service provided prostitutes to judges and U.S. congressmen. They also provided workers to ranches (including a ranch owned by President Lyndon B. Johnson), and deported the workers just before payday. Grandin summarizes the unbridled power of these agents: “There are few places patrollers can’t search, no property belonging to migrants they can’t seize. And there is hardly anybody they can’t kill, provided that the victims are poor Mexican or Central American migrants.” He emphasizes the agency’s long, brutal history.

Now that the budget of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the largest enforcement agency of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), is enormous, President Trump appears to want to utilize its officers (and other DHS officers) as a presidential militia, much like Texas governors used to deploy the Texas Rangers. Why did Trump dispatch more than 100 militarized federal agents to Portland, of all cities? George Lakey says Trump expected Portland demonstrators to fight back, and thus provide “video footage” for Trump’s law-and-order reelection campaign. (“Understanding Trump’s game plan in Portland could be the key to preventing a coup in November,” Waging Nonviolenc, July 25, 2020.)

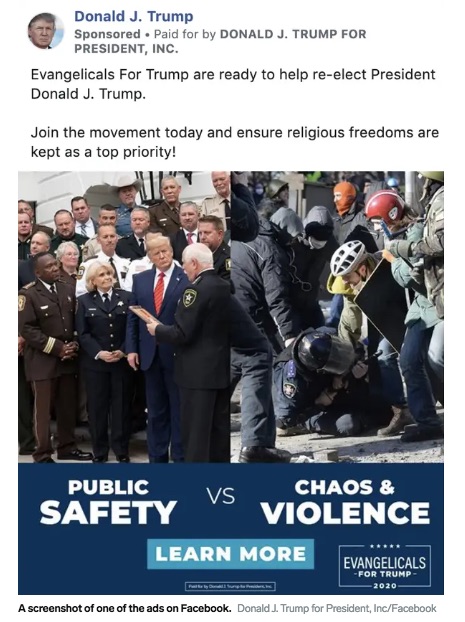

Screenshot of Trump reelection campaign advertisement on Facebook, pairing images of Trump listening to law enforcement officers in the U.S. with pro-democracy demonstrators attacking a fallen policeman in Kyiv, Ukraine, 2014. Source: Business Insider, July 22, 2020.

This argument is compelling, especially since the Trump campaign is apparently so desperate for imagery that it recently used a 2014 photograph from Ukraine.

Variously boasting of 50,00 to 75,000 federal officers, Trump told Fox News during a July 23, 2020 telephone call: “We’ll go into all of the cities… .” However, as Peter Vincent, a former general counsel for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), points out: “the Department of Homeland Security was never intended as a national police force let alone a presidential militia” (Associated Press, July 25, 2020). As this article goes to press, Trump removed Federal agents from the frontline in Portland. See Guardian news video, July 31, 2020, for footage and analysis.

Ed Pilkington, writing in the July 24, 2020 Guardian, builds a case that BORTAC, the elite border patrol tactical unit that President Trump deployed against protesters in Portland, is singularly unsuited for that role. He notes that BORTAC has been deployed in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Latin America, and has “no apparent training in crowd control or the policing of protests.” Pilkington quotes Jenn Budd, a former senior border patrol agent, who calls BORTAC among “the most violent and racist in all law enforcement.” Moreover, she says, they treat people “as enemy combatants, meaning they have virtually no rights.” James Tomsheck, a former internal affairs investigator in the CBP between 2006 and 2014, found many cases of inappropriate lethal force, used primarily against Mexican citizens. The Southern Border Community Coalition has tracked 111 deaths attributed to border patrols since January, 2010. A. C. Thompson, writing in Propublica on July 1, 2019, exposed a secret Facebook group of current and former border patrol agents who shared racist and sexist comments and memes, including an altered photograph “of a smiling President Donald Trump forcing [Congresswoman] Ocasio-Cortez’s head toward his crotch.” Tomshek cautions: “Border patrol has always seen itself as a militarized force, and that aspiration is now being enabled by the current administration.”

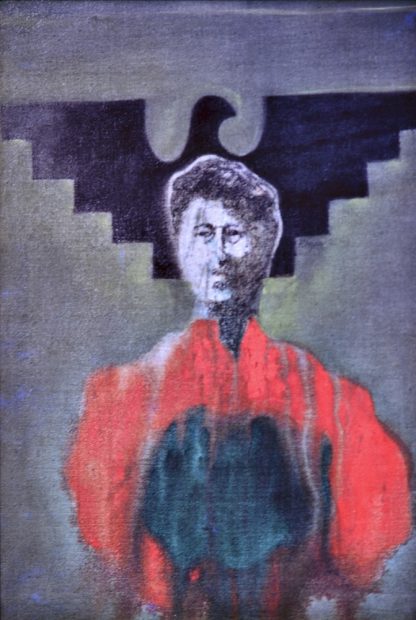

Felipe Reyes (b. 1944), Sacred Conflict, c. 1971, acrylic on canvas, 24 x 36 inches, private collection, photograph by Ruben C. Cordova.

When Sacred Conflict was made, many Texans would likely have considered it to be as provocative as Instant Genocide (treated in Part 1), because it dared to show the church of the Mísion San Antonio de Valero (popularly known as the Alamo) with the UFW flag flying over it.

The Alamo narrative is the centerpiece of official Texas history: it certifies Mexicans as villains and their descendents as “subjugated enemies,” as David Montejano puts it in Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986. This narrative is a mythic original sin from which there can be no expiation or redemption. It served to justify the Mexican-American War, a war of conquest against Mexico, as well as continued oppression against Mexicans and their descendents. As the defining emblem of the Chicano movement, the UFW flag served as an image of Chicano unity, resistance, and empowerment, and thus as a counter-Alamo symbol.

Reyes published the following analysis of Sacred Conflict in the April, 1972 issue of Magazín:

“Throughout this painting is an intermingling of ironic symbols. The Alamo means different things to different peoples. To the Anglos it represents what they call oppression by Mexican tyrants. But to the Chicanos the Alamo is the symbol of Anglo aggression. The Chicano flag over it represents our viewpoint, that is, that the Alamo was a victory for us, the Chicanos. Yet the Anglos claim the whole event as their victory. In a way the Alamo is a sacred symbol. It is an event trapped in the past, it is something beyond our manipulations and therefore something beyond criticism. But the different attitudes force me to apply meaning to this symbol. To be brief, the Alamo to me represents vengeance for the Chicano, and the flag is the Chicano symbol for justice.”

The “lessons” Reyes draws from the Alamo battle counter the standard narrative: he sees Anglo aggression rather than Mexican tyranny and cruelty; the Mexican forces were the victors, rather than the losers; most importantly, it is a call for justice for Chicanos. The UFW flag stands in for the Mexican flag, as the banner of Mexico’s successors. It is a flag of victory that, as I note in my book Con Safo: The Chicano Art Group and the Politics of South Texas (2009), “connects past struggles with present struggles and extrapolates a future victory from a historical victory.” Thus, the Alamo, “the symbol of vengeance against Chicanos is repositioned as a symbol of justice and ‘vengeance for the Chicano.’”

Reyes’ Sacred Conflict inaugurated a line of powerful artistic critiques of Alamo mythology, including works by several members of the Con Safo group, which is why I placed this painting at the beginning of my exhibition The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth in 2018.

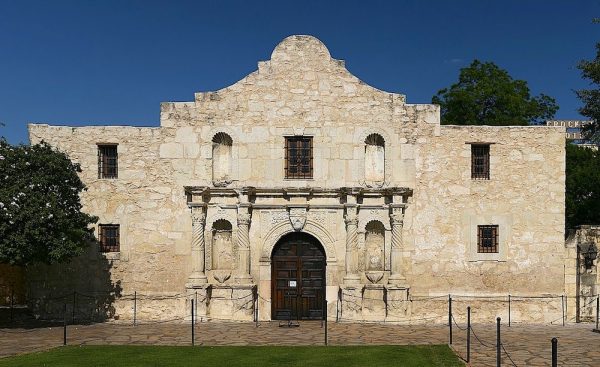

The Alamo church building, from Wikipedia (image cropped to focus on building). Photograph by Daniel Schwen, 2009.

Reyes replicated the present state of the Alamo, with its anomalous, Taco Bell-like “hump” at the top of the façade. He compressed the building horizontally, and he elongated the first story, which makes the second story seem even smaller. Reyes exaggerated the scale of the hump and its sharp-angled irregularity. Reyes’ hump recalls the top of a piece of crudely carved wood furniture, to which the Alamo hump has been derisively compared. The cumulative effect is that Reyes’ Alamo church is more “Gothic” than the existing church. That is to say that it is even more bizarre and further removed from Spanish colonial architecture.

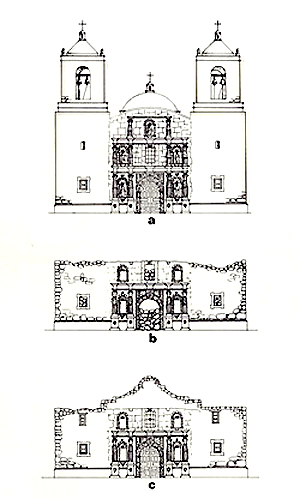

Plans of the Alamo church: a) as it would have appeared when fully completed, with three stories, a central dome, and flanking bell towers; b) hump-less and roofless, as it appeared at the time of the 1836 battle; c) as it appears today, with the U.S. Army-built hump. Source: Center for Archaeological Research, UT-San Antonio, from Texas Almanac, Texas State Historical Association.

When completed, the Alamo church would have been three stories high, with a central dome over its crossing, and tall, flanking bell towers, instead of what it is now: a hump-crowned stump of a church. The Sons of Dewitt Colony maintains an excellent pictorial archive of renderings of the church.

The Alamo’s hump, the roof it conceals, and the upper pair of flanking windows were added by the U.S. Army c. 1850 when they converted the roofless ruin into a storehouse. See: John Nova Lomax, “How the Alamo got its Hump” in Texas Monthly (2018).

The Alamo website celebrates the anomalous, Army-built hump. It even credits the hump with making the Alamo church a symbol of freedom: “The profile of the building, as a result of this rounded cresting, has become an iconic symbol of the quest of [sic] freedom.”

One crucial matter that has received much deserved attention in recent years is the connection between Anglo American colonization and the enslavement of Blacks. The rebellion against Mexico — in addition to a land-grab — was a war to preserve the institutions of slavery that Anglo American colonists had modeled on those that existed in slave states. The Republic of Texas was a slave republic, from which it transitioned into a slave state and then a Confederate state. The Alamo is still perversely presented as a symbol of freedom in Texas and the U.S., but, according to a Confederate veteran, who was interviewed by the San Antonio Express in 1917, a platform on the second floor of the Long Barrack served as “an old slave market,” where enslaved people were auctioned. See: Mario Marcel Salas, “Bet You Don’t Know, Slaves were Sold at the Alamo,” The San Antonio Observer, April 3, 2018.

Felipe Reyes (b. 1944), Lettuce Prey, c. 1971-72, watercolor and gouache on canvas, dimensions unknown, location unknown. Photograph and reproduction courtesy of Cesar Martinez.

Stylistically, Lettuce Prey utilizes thin washes and blurred, dripping techniques influenced by Arshile Gorky. A starkly outlined UFW Eagle frames Chávez’s head. Its head more closely resembles that of a dove of peace than a powerful raptor, which is consistent with Chavez’s organizing philosophy. By framing Chávez with a bird, Reyes implies Chávez is the “spirit” of the UFW. Chávez’s bright orange-red shirt references the color scheme of the UFW emblem. It also creates maximum contrast with the blurry, gray-green background, as well as with the greenish-black head of lettuce that floats before him like a phantasm.

Chávez’s organizing philosophy was non-violent and infused with religious devotion, which served to blunt the habitual red-baiting attacks that were directed against organized labor. Masses, prayers, and fasts were deliberately prominent activities, and even marches were likened to pilgrimages. The title Lettuce Prey is a punning reference to the Latin injunction oremus (let us pray) used in the Catholic Mass. But while Reyes’ title sounds like a call to prayer, it is actually a condemnation of social and economic predation. It was made in support of the California lettuce strike launched in 1970, the largest farm worker strike in U.S. history. Reyes considers Chicanos — and the working class in general — to be “the prey of the moneyed interests.” Agribusiness, he says, is “especially predatory.”

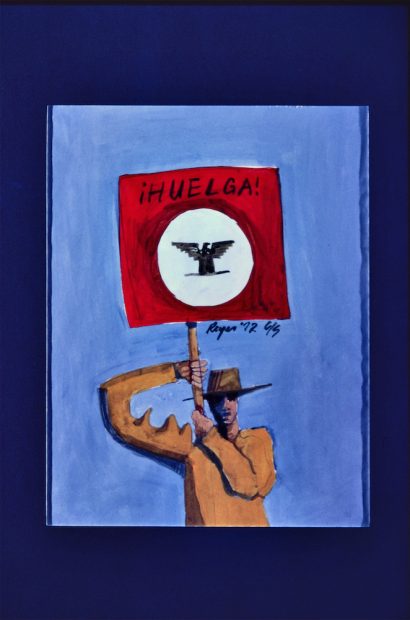

Felipe Reyes (b. 1944), ¡Huelga! (Strike), dated 1972, pen, watercolor, and gouache on paper, dimensions unknown, location unknown. Photograph and reproduction courtesy of Cesar Martinez.

¡Huelga!, was made in a more humorous vein. A hat-wearing man in a camel-colored shirt holds a UFW placard. But why does his elongated right arm have three bulges: are these muscles that show the might of the union, or are they punning references to camel humps? Reyes thinks this image was used for the cover of a UFW pamphlet. If so, we have not been able to locate a copy.

The works in this article emphasize the union between the UFW and the Chicano movement. Part 3 will discuss Reyes’ art pertaining to struggles for political representation and social services in San Antonio and the Rio Grande Valley, and concludes with two additional works that feature UFW imagery.

****

My thanks to Bill Fisher for providing me with digital scans of the two pertinent issues of Magazín. The discussion of Sacred Conflict incorporates material from my catalogue The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth (2018).

****

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator. Felipe Reyes has figured prominently in all of his writings on the Con Safo art group. Cordova has curated ten solo exhibitions devoted to Con Safo artists: Felipe Reyes (“Barrio Dogs and the Cholo Landscape,” 2006); Jesse Almazán (Memorial Exhibition, 2007); Jesse Treviño Retrospective (2009-10); Mel Casas (Memorial Exhibition, 2014); Mel Casas (a four-part retrospective of the Humanscape cycle, 2015); Roberto Gonzalez (“Sacred Waters,” 2016); Mel Casas (“American History Does Not Begin with the White Man: Indigenous Themes in the Work of Mel Casas,” 2018). He is currently working on a retrospective for group artist Rolando Briseño.