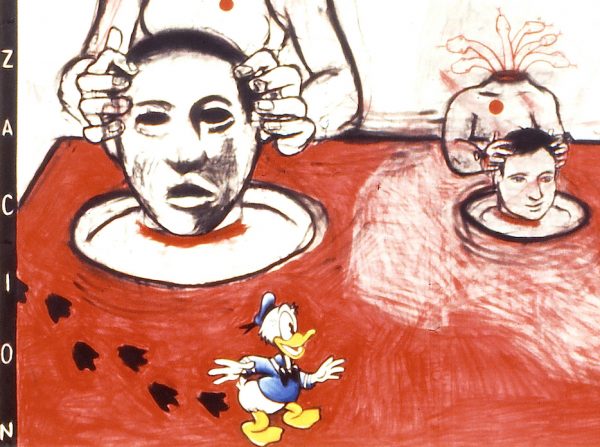

Enrique Chagoya, Goya Meets Posada (Goya conoce a Posada), from Homage to Goya II: Disasters of War, 1987, published 2003, etching with aquatint and red rubber stamp, sheet 13 x 15.”

To read part one of this series, please go here.

Para leer este artículo en español, por favor vaya aquí. To read this article in Spanish, please go here.

I caught up with the marvelous artist Enrique Chagoya when he lectured recently at the San Antonio Museum of Art. This is a sequel to the article Enrique Chagoya’s Superheroes and Super Villains written for Glasstire on that occasion (henceforth referred to as Chagoya 1). Refer to it for an overview of Chagoya’s background and formative experiences, for here we are jumping right into a discussion of more heroes and villains.

Not surprisingly, Francisco Goya (1746-1824) is Chagoya’s favorite European artist, and José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913) is his favorite Mexican artist. Both Goya and Posada made caustic, satiric prints that were — and still are — among the most influential works in the history of art. Here Chagoya brings the two satiric masters together, though their lives did not overlap.

Francisco Goya, Plate D from the Proverbs (one of four plates prepared for, but not published in the set), c. 1816-23 (published posthumously, before 1877), etching, aquatint, and drypoint, sheet 10 13/16 x 14 15/16,” Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In the above image, what appear to be Surrealistically floating bulls reference one of Goya’s favorite motifs. Goya did an entire series dedicated to bulls called the Tauromaquia (Bullfighting) series. The bulls in this print, however, derive from an enigmatic print Goya did for his Proverbs series. It is sometimes referred to as the Rain of Bulls. Chagoya has fragmented and redistributed these bulls.

Diane Manuel, who notes that Chagoya regards Goya as “the first of the modern artists,” recorded this Chagoya quip in Stanford Today in 1997: “He [Goya] was exploring the unconscious and dealing with dream imagery all the time.” Thus Chagoya’s floating, fragmentary bulls extend Goya’s incipient modernism and proto-Surrealism and make him even more modern.

Posada and Goya are accompanied by a skeletal personage now known as Catrina. She is the most referenced character in Mexican art. Posada invented her as a head-and-shoulders image for a Day of the Dead broadside.

José Guadalupe Posada, image created for Day of the Dead broadside (now known as Catrina), image design c. 1910, first printed 1913.

Like the image of Goya’s bulls that Chagoya draws on for Goya Meets Posada, Posada’s print was also published posthumously. The skeletal woman was later elaborated into a full figure by Diego Rivera. Rivera did this in a large mural filled with historical portraits called Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Park (1946-47). Fittingly, Rivera also enthusiastically compared Posada to Goya. Chagoya, in his Archives of American Art interview with Paul Karlstrom in 2001 refers to Posada as “almost like an origin of Mexican modernism.” So Chagoya has united the pioneers of modernism in Europe and Mexico through the agency of death, represented by the figure of Catrina, who makes the introduction. She is delighted to bring these masters together, even if, as Chagoya notes, it is in the middle of a “bull storm.”

In his Alameda mural, Rivera depicted himself as a mischievous child who is holding Catrina’s hand. Chagoya includes a kindred self-portrait in the lower right corner: “I wanted to be present as if I were a child, hence the roller skates.” He is wearing a Nahua culture Crocodile (Caymán) mask and dance custom from the Mexican state of Guerrero. It is one of many folk dance masks he has collected from Mexico. As Chagoya roller skates away, he is shadowed by a spirit after-image. “The rationale is that of a dream,” adds Chagoya, “in other words there’s no rationale.”

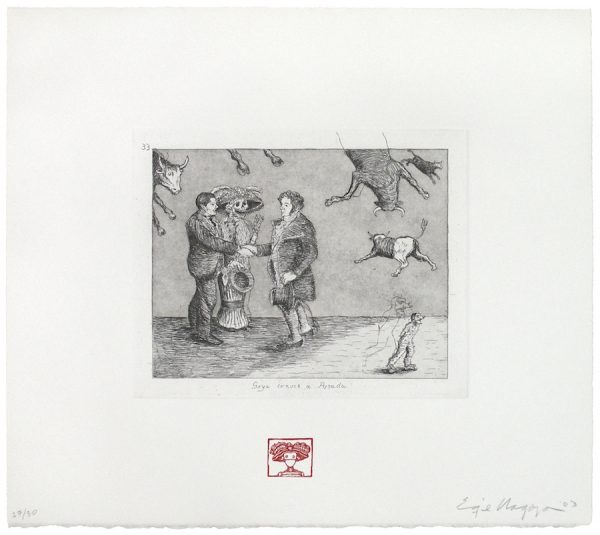

Enrique Chagoya, Contra el bien general. (Against the common good.) from Homage to Goya II: The Disasters of War, 1983, published 2003, etching with aquatint and red rubber stamp, sheet 13 x 15 inches.

Sarah Kirk Hanley, writing in Art in Print in 2013, declares that Chagoya is “the artist who has most effectively demonstrated the uncanny relevance of Goya’s political satire to our own times.” She adds that Chagoya has appropriated and transformed more than 30 Goya etchings since 1983, “altering each by deft substitutions that pinpoint our own social ills.” As Hanley observes, Chagoya’s “reverence” for Goya is significant: his conscientious mode of emulation enables him to deploy the compelling power of Goya’s compositions. Oftentimes, appropriation works best when the fewest changes are necessary. Chagoya tries to reproduce Goya’s compositions and his individual marks as closely as possible. He traces reproductions of Goya’s prints and transfers the drawings in reverse onto his plates. When Chagoya uses his stylus on a plate, he has to make his hand shake to emulate Goya’s lines, leading him to conclude that Goya had a trembling hand. He told Hanley this revelation was “perhaps my closest communication with Goya’s ghost.”

This was the first print Chagoya made after Goya. He was an undergraduate at the Art Institute of San Francisco, and his class with Robert Flynn Johnson gave him access to Goya’s prints at the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts (a component of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco housed in the Legion of Honor). This print also required the least change: Chagoya simply substituted President Ronald Reagan’s head for that of a demonic, bat-wing-eared scribe in the Goya. The batty, talon-fingered and talon-toed Reagan is locked in concentration as he raises his left hand. Evidently, the memory-challenged president is struggling to recall something that he records in a large book. The consequences are evident in the background, where throngs of people on both sides of him are gripped by despair.

The stamps Chagoya applies to his prints after Goya are a sardonic commentary on the stamps applied to Goya’s prints in the Spanish National Library by the administration of General Francisco Franco, whose fascist regime Goya certainly would have opposed. This stamp reads: “Museo de Antiguedades Absurdas (Museum of Absurd Antiquities).” Chagoya’s stamp image can also be understood as a gesture of mockery: cuckold is among the meanings of this mano cornuto (horned hand). Finally, one has to appreciate the coincidental economy and double-meanings of Goya’s/Chagoya’s title. Chagoya was deeply angered by Reagan’s support of the Contras in Nicaragua when he made this print. (For a comprehensive reference to this complex enterprise, see Understanding the Iran-Contra Affair. Also see the discussion of Double Agent in Chagoya 1.) As Chagoya enjoys pointing out, “Contra,” which means “against” in Spanish, was already in Goya’s title. And while “el bien general” translates as “the general good,” it also reads (as a literal, word-for-word translation) as “the good general.”

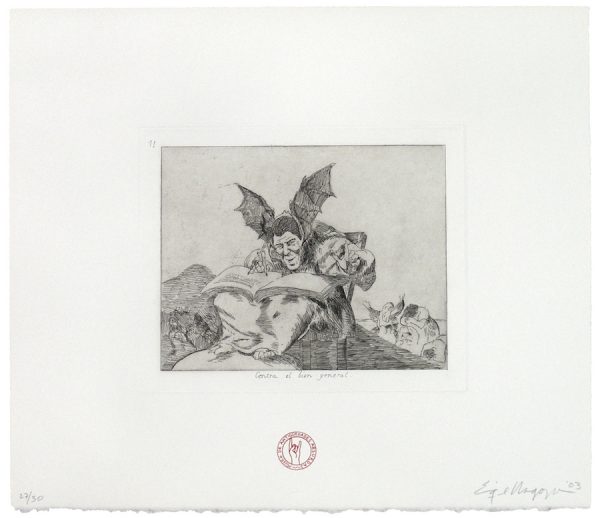

Enrico Mazzanti, illustration of Pinocchio made for the first edition of Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio, published in 1883, (originally in black and white, this version was colored by Daniel Donna).

Nose Job, which is one of Chagoya’s most powerful images, was featured on the cover of the catalogue When Paradise Arrived, a retrospective held at the Alternative Museum in New York in 1989. Chagoya depicts President Ronald Reagan as Pinocchio, a puppet and a liar who, in Carlo Collodi’s original story (initially serialized beginning in 1881 and published as a book in 1883), suffered many tribulations due to his bad behavior. Italian depictions of Pinocchio, including contemporary puppets, follow Enrico Mazzanti’s first edition illustration. It features a long-nosed, rail thin boy. He wears a long, old-fashioned shirt with a ruffled collar, and he has a tall (but very simple) peaked hat.

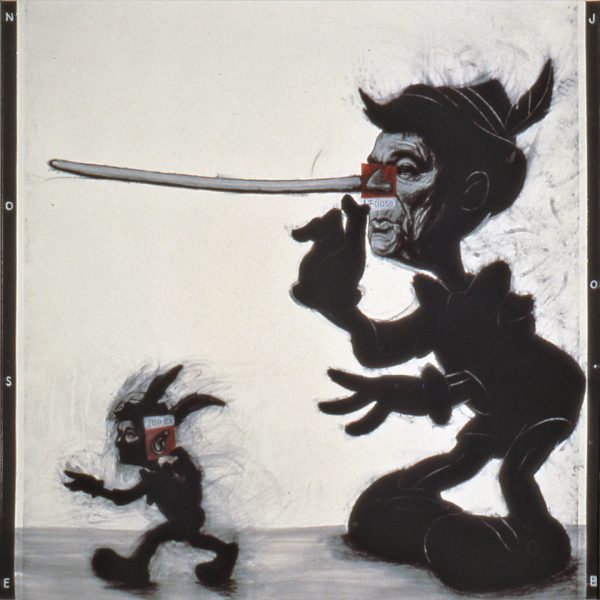

Enrique Chagoya, Nose Job, 1989, charcoal and pastel on paper, 80 x 80”, private collection, © Enrique Chagoya, courtesy the artist and George Adams Gallery, New York

Chagoya’s Reagan/Pinocchio is based on the 1940 Disney animated film rather than Italian models. Walt Disney rejected the early Italian-style work of his animators because he thought it was unappealing. The Disney studio Aryanized Pinocchio by putting him in a Tyrolean (Bavarian) feathered hat and giving him blue eyes. He was endowed with a giant bow tie and a short-sleeved shirt. Most dramatically, he literally received a Mickey Mouse makeover. His proportions, as well as the other elements of his costume, derive from Disney’s franchise star. He is short, with a giant head and giant eyes, and oversized, white-gloved hands. His short red pants (Italian versions have green pants and a red shirt), and the enormous children’s shoes are also taken from Mickey. Since Disney’s Pinocchio is a Mickey Mouse hybrid, its utilization in this drawing carries the implication that Reagan is a “Mickey Mouse” president in the derogatory, slang meanings of the term: silly, stupid, trivial, shoddy, and substandard. Chagoya’s first large-scale drawing, done in 1984, was an image of Reagan as Mickey Mouse called Their Freedom of Expression. The Recovery of Their Economy (see Chagoya 1). As Chagoya told Diane Manuel in 1997: “I wanted to do an image of a politician, but I didn’t want to make an evil-looking monster with traditional shark teeth. Instead, I preferred a harmless look because that’s the way politicians represent themselves to the public — always with the best face. And Ronald Reagan, to me, was a Mickey Mouse kind of character.”

In Nose Job, Reagan/Pinocchio is both puppet (controlled by unseen others) and puppet-master (in his capacity as the nation’s commander-in-chief). Reagan’s puppet nature is emphasized by the beveled edges of his limbs, which are carved from wood. The big puppet’s unnatural pose confirms that he is in the process of being lifted off of the ground by hidden strings. Like other puppets, Reagan is incapable of standing on his own feet. His telescopic nose exposes his serial dishonesty as it extends all the way across the upper portion of the paper surface. In a vain and childish attempt to conceal his obvious dishonesty, Reagan has pasted a color photograph of his “normal” nose over the base of his long, lying Pinocchio nose.

In the lower left, a diminutive dopplegänger sprouts enormous donkey ears, which he carelessly tries to hide with an upside-down color photograph of a human ear. Who then, is this masked man? One might assume he is Oliver North, the point man for the Iran-Contra scandal, or Reagan’s Vice President, George H. W. Bush, formerly director of the C.I.A. (1976-77), who was also a central figure in Iran-Contra. Instead, it is a second image of Reagan. The donkey ears refer to Pinocchio’s partial transformation into a donkey. Bad boys are transformed into donkeys at Pleasure Island (perhaps Reagan’s equivalent is Rancho Mirage), and after that they are sold, to labor as beasts. The implication is that Reagan, through continuous bad behavior, had lost the right to be part of the human species. Pinocchio escaped his beastly punishment by escaping from Pleasure Island. Reagan escaped his punishment, too, which should have been prison, largely through denials and destruction and withholding of evidence.

Oliver North, after he destroyed original documents and substituted forgeries for them, went on trial for his role in the Iran-Contra criminal enterprise in February of 1989. He was given a slap-on-the-wrist sentence in May. Five administration officials who had been convicted for their roles in Iran-Contra (as well as Caspar Weinberger, who had not yet been tried) were pardoned by President H. W. Bush near the end of his term (he was advised by Attorney General William P. Barr). The pardon of Weinberger prevented Bush himself from being tried and convicted. Chagoya recalls that Nose Job was “done after the Iran-Contra scandal, when Reagan claimed that he did not remember any of the criminal behavior behind the scandal.” Reagan’s administration was pervaded by deceit, obstruction, and amnesia. The latter was sometimes real, sometimes feigned.

Reagan’s “memory” only got worse. In a February 1990 deposition for the trial of John Poindexter, Reagan’s former national security advisor, former President Reagan claimed he could not recall answers to questions 88 times. He was unable to identify Gen. John Vessey, his chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff for three years. Reagan also claimed he “never had any inkling” North had diverted funds to the Contras. Reagan the old actor was, however, able to recite his Cold War Domino Theory script, saying the Soviets aimed to “take Eastern Europe … organize the hordes of Asia and … move on to Latin America. And once having taken that … the United States would fall into their outstretched hand like overripe fruit.”

Robert Parry, who uncovered important parts of the Iran-Contra scandal, notes that even many Democrats and editors didn’t want to know the truth. Writing for Consortium News in 2011, he notes that the illegal behavior likely began before Reagan’s election: Reagan likely promised arms to Iran in order to prevent President Carter from winning release of the U.S. hostages. Parry concludes: “The [Iran-Contra] scandal’s failure to achieve meaningful accountability for high-level lawbreakers can be seen as a key turning point in modern American history.” Fittingly, it is the origin of the expression “post-truth.”

Enrique Chagoya, Tribute to Posada, 1989, charcoal and pastel on paper, 80 x 80”, private collection, © Enrique Chagoya, courtesy the artist and George Adams Gallery, New York.

Tribute to Posada was made for a Day of the Dead exhibition in 1989. It features an enormous skeletal figure and a diminutive skeletal self-portrait. Both images are made more macabre by the superimposition of a linear smiley face rendered in bright red. The red eyes impart a fiendish quality to both skulls. The manner in which the linear red smile bisects the grimacing teeth in the upper and lower jaws of both characters is particularly unsettling. Chagoya provides two other red accents: a red rose for the woman, and a red tie for himself.

Chagoya believes Posada’s engravings and lithographs “incarnate the spirit of the Mexican people of his time.” He particularly admires Posada’s annual calavera images made for Day of the Dead, which he judges the “most accomplished and popular.” Posada’s influence was immense in Europe as well as Mexico, and Chagoya adds that “it is still alive today in many popular arts and crafts during celebrations for Day of the Dead in Mexico and now in the US.”

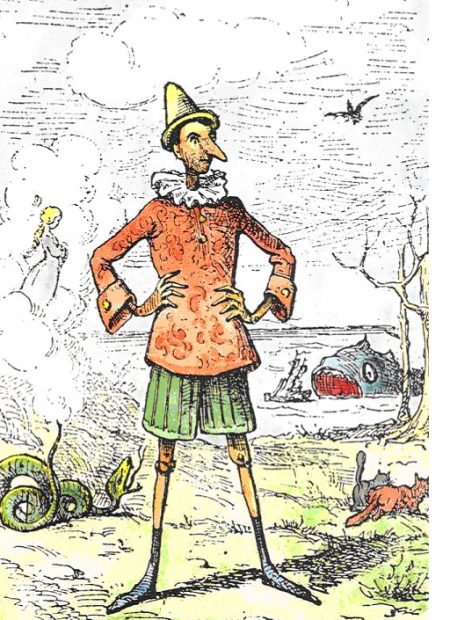

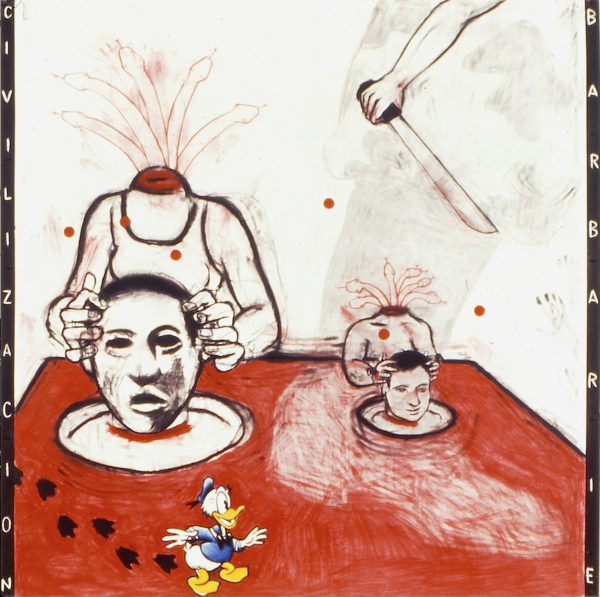

Enrique Chagoya, Civilización y Barbarie (Civilization and Barbarism), 1992, charcoal and pastel on paper, 80 x 80”, private collection.

Chagoya’s title references the book Facundo: Civilización y Barbarie (1845) by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento — a foundational text that has been called the most influential Latin American book ever written. Sarmiento, who would later become president of Argentina, laid out a dichotomy in which “civilization” is associated with Northern Europe, North America, and cities. He associated “barbarism” with Latin America, Spain, and the countryside. Chagoya’s drawing is an exploration of that dichotomy in a contemporary context. The artist describes it as a response to “several massacres in El Salvador conducted by the military dictatorship sponsored by the US in the late 1980s and early 1990s.” These include: the abduction, rape, and murder of U.S. Maryknoll nuns and a lay worker who accompanied them; the murder of Monsignor (now Saint) Oscar Romero, who was assassinated while he was saying mass; the El Mosote massacre, in which about 1,200 men, women, and children were murdered (some after being tortured and raped) by the Atlacatl Battalion, which was created, trained, supplied, and funded by the U.S. It had recently returned from three months of counterinsurgency training in the U.S. (As Noam Chomsky notes, many of the worst atrocities it committed took place after U.S. training sessions.) Raymond Bonner, writing in The Atlantic in 2018, notes that in the early 1980s El Salvador received the third highest amount of foreign aid from the U.S. because “for Reagan, El Salvador was the place to draw the line in the sand against communism.” Chomsky, in his book What Uncle Sam Really Wants (1991) provides a systemic analysis: “US aid has tended to flow to Latin American governments which torture their citizens.” The U.S.’s preferred agro-export model impoverishes the populace, and when they are driven to resist, the U.S. supports brutal regimes that use violence and torture to crush resistance.

Chagoya’s Civilización y Barbarie takes place in a room with a bloody table. Two figures are decapitated. The snakes that extend from the headless torsos are pre-Columbian symbols of gushing blood. On the left, a headless woman holds an eyeless head that resembles a Mesoamerican mask. On the right a boy holds his own decapitated head. This horrific scene was inspired by an actual event recounted in Chomsky’s What Uncle Sam Really Wants, which Chagoya had read shortly before making this drawing. Catholic priest Daniel Santiago “tells of a peasant woman who returned home one day to find her three children, her mother and her sister sitting around a table, each with its own decapitated head placed carefully on the table in front of the body, the hands arranged on top ‘as if each body was stroking its own head.’” Chomsky continues: “The assassins, from the Salvadoran National Guard, had found it hard to keep the head of an 18-month-old baby in place, so they nailed the hands onto it. A large plastic bowl filled with blood was tastefully displayed in the center of the table.”

The machete in the upper right is the decapitating weapon. Security forces often used machetes to chop people to death. A shadowy boot with a camouflaged leg alludes to the U.S.-trained and supported death-squad torturers. Chomsky highlights the sadistic practices of the Salvadoran troops: they would force parents to watch as they dragged their children over barbed wire until their flesh was torn from their bones; decapitated heads on pikes dotted the landscape; men’s genitals were stuffed into their decapitated heads; after women were raped their wombs were excised and displayed on their faces.

Donald Duck makes a surprise entrance in Civilización y Barbarie as a debased, commercialized savior figure that miraculously walks on a sea of blood (or at least a table top) rather than a sea of water. Instead of leaving bloody footprints, his palmate feet efface the blood evidence. If he just walks around enough, perhaps he can hide all traces of blood. Looks are often deceiving, so this duck can be just as harmful and deadly as any jack-booted villain. Donald Duck suggests the great power of otherwise unseen forces: the U.S. politicians, diplomats, “trainers,” and businessmen who implement and profit from the policies that result in massacres in Latin America. The red dots are inspired by John Baldessari, who has used dots to efface heads in photographs. Here they could refer to bullet holes. As the artist explained to Diane Manuel: “Sometimes I don’t even know what they [my paintings] mean… . My works deal with a lot of opposites, and their interaction produces a third element, a synthesis, that occurs in the mind of the viewer. I put images together and the interaction creates an imagery that makes its own kind of sense, like a dream — or perhaps a nightmare.”

Chagoya was very interested in Salvadoran politics: “At the time I was interacting with local solidarity committees with Central America and also met some Salvadorian artists living in San Francisco. I went to El Salvador during the first democratic elections as an independent observer for the election process. The great spirit of the time and the hopes of the people there left an impression on me because there were big hopes for democracy (sadly we now know how it went).”

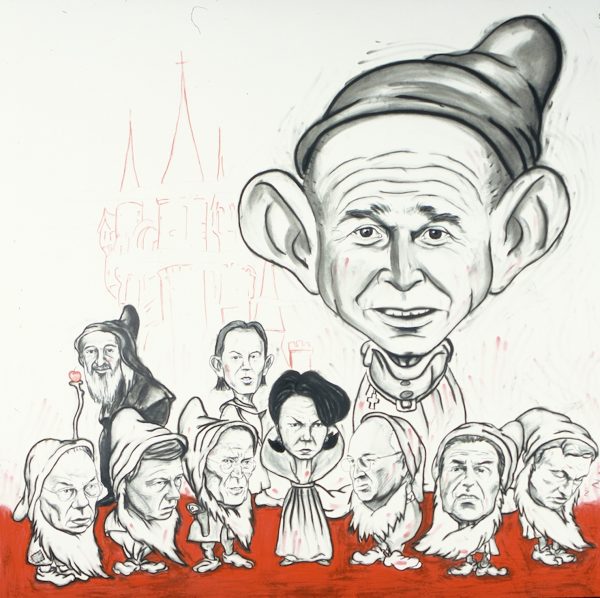

Enrique Chagoya, Untitled (Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs), 2004, charcoal and pastel on paper, 80 x 80”, private collection.

Chagoya says this drawing, which is based on Disney’s animated film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), is “open to many interpretations.” He adds that “the characters’ names in the Disney movie may match the personalities of the people portrayed in the Bush administration,” and he challenges the viewer to essentially pin the tails on the donkeys (or elephants, as the case may be). I take up this challenge here. It doesn’t take any detective work to see that president George W. Bush is Dopey. George Tenet, Director of the C.I.A. who was blamed for the 9/11 attack and other intelligence failures, is Sleepy, on the far right. Paul Wolfowitz, the Deputy Defense Secretary, is on Sleepy’s left. Ironically, Condoleezza Rice (National Security Advisor 2001-05; Secretary of State 2005-09), who is a black woman, has to be Snow White, the “fairest in the land” (which is why her mother the Queen wanted her killed). Snow White looks grumpier than everyone else, with the possible exception of Vice President Dick Cheney (directly below Bush), who has got to be the Grumpiest dwarf in the land. Doc is the dwarf leader, so Cheney should be Doc, since he was essentially the real president. Of course, Colin Powell (Secretary of State, 2001-05, on the far left) played a key role in leading the U.S. (and its coalition) into war with Iraq on false pretenses (weapons of mass destruction), which could serve as justification for making him Doc. Though Powell later attributed his misrepresentations in his infamous U.N. Security Council speech in 2003 to “great” failures of intelligence, Jon Schwarz, writing in The Intercept in 2018 points out that the State Department’s intelligence staff (INR) contradicted one claim, and judged others “weak,” “not credible,” or “highly questionable,” but Powell could not be dissuaded from delivering his dubious speech.

Attorney General John Ashcroft is next to Powell. And the pistol-packing dwarf is obviously Bush’s Secretary of Defense (2001-05) Donald Rumsfeld — but who knows what his dwarf name might be. Dwarf Vader, perhaps? Osama bin Laden, the founder of Al-Qaeda who was responsible for 9/11 and other attacks on the U.S., is the evil Queen, in her witch guise. This makes him a bearded-lady cross-dresser, and he seems quite ecstatic about it (or perhaps it is joy at the thought of the havoc he wreaks). Only Bush seems as happy as bin Laden, though in a witless, Alfred E. Neuman mode of “what me worry?” nonchalance. 9/11 didn’t get him down. The humiliation of the 9/11 attack provided Bush with the pretext for the misdirected war with Iraq, allowing him to humiliate its leader Saddam Hussein, who had remained defiant even after W’s father had defeated him. Ahsan I. Butt, writing in Al Jazeera in 2019, views it as an example of the “Ledeen Doctrine” wherein the U.S. periodically crushes another country purely for “demonstration effect,” to “reassert its position as an unchallengeable hegemon.”

Returning to Chagoya’s drawing, bin Laden bears the poisoned apple that will induce Snow White’s “sleeping death,” until a wandering prince resuscitates her with “love’s first kiss.” That fair prince, already visible in the background, is Tony Blair, the U.K. Prime Minister who became Bush’s primary coalition partner, and who was subsequently also deemed guilty of misrepresenting the “threat” posed by Iraq. A fairy tale castle shimmers in the distance, but it is an illusory edifice, fashioned from the blood on which the dwarfs stand. The myth of Camelot is no longer tenable: the blood of countless people has been shed in the Iraq War and its aftermath, purportedly to make the world safe by seizing the phantom weapons of mass destruction. In 2018, Salon estimated the ongoing death total at 2.4 million. As Schwarz points out, “Powell’s loyalty to Bush extended to being willing to deceive the world: the United Nations, Americans, and the coalition troops about to be sent to kill and die in Iraq.” César Chelala, writing in Common Dreams in 2018, notes that the Iraq war not only “nearly destroyed” Iraq, it also “destabilized the whole region by intensifying internecine and religious conflicts and giving rise to new and violent groups” such as ISIS. Chelala concludes: “nothing will assuage the savage wounds of this senseless war.” Chagoya has rendered a grim fairy tale, not a Brothers Grimm Fairy Tale.

The third installment of this series, Chagoya III: Yet More Heroes and Villains, will begin where we left off, with Osama bin Laden, George W. Bush, and members of his cabinet.

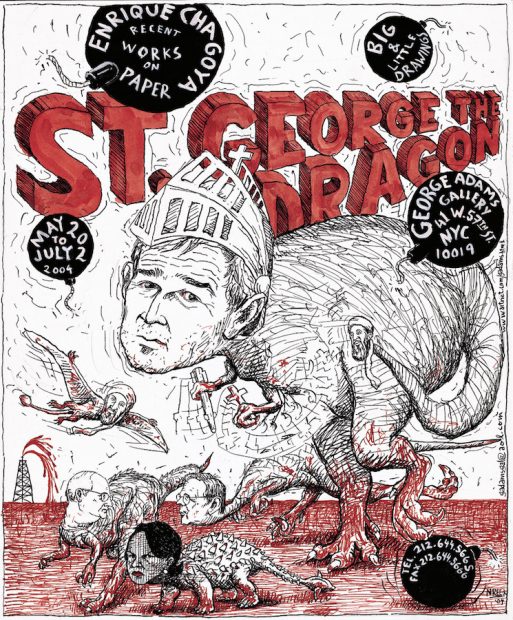

Enrique Chagoya, St. George the Dragon, 2004, ink and acrylic on paper (exhibition announcement poster), 14 x 11 ½”, collection of the artist, © Enrique Chagoya, courtesy the artist and George Adams Gallery, New York.

***

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator. His next curatorial project, The Day of the Dead in Art, opens at Centro de Artes (the former Museo Alameda) in San Antonio on October 24. It will feature a print by Chagoya, as well as vintage prints by Posada (including Catrina) and his contemporaries. Most of the artists in the exhibition were deeply influenced by Posada, and two of them (Artemio Rodríguez and Carlos Cortez) wrote books about him.