Jusepe de Ribera, Saint Jerome (det. of angel blowing trumpet of Last Judgement), 1626. Oil on canvas, 105 1/8 × 64 9/16 in. Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

Though the word “masterpiece” is used too freely, the 41 works in the Kimbell exhibition Flesh and Blood: Italian Masterpieces from the Capodimonte Museum include a murderer’s row of masterpieces by some of the most storied names in Western art, including Titian, Parmigianino, El Greco, Caravaggio, Annibale Carracci, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Juseppe de Ribera. Very few U.S. museums — notably the National Gallery, the Frick Collection, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the J. Paul Getty Museum — could muster a group of Renaissance and Baroque highlights of comparable caliber. Flesh & Blood is one of best exhibitions of Old Masters to tour the U.S. in recent decades, and the Kimbell Museum is one of only two U.S. venues. (It was previously at the Seattle Art Museum.) Just one of Flesh and Blood’s choice works could be the worthy subject of a mini-exhibition, as was Parmigianino’s Antea (c. 1531-34), when it was exhibited at the Frick Collection in New York in 2008.

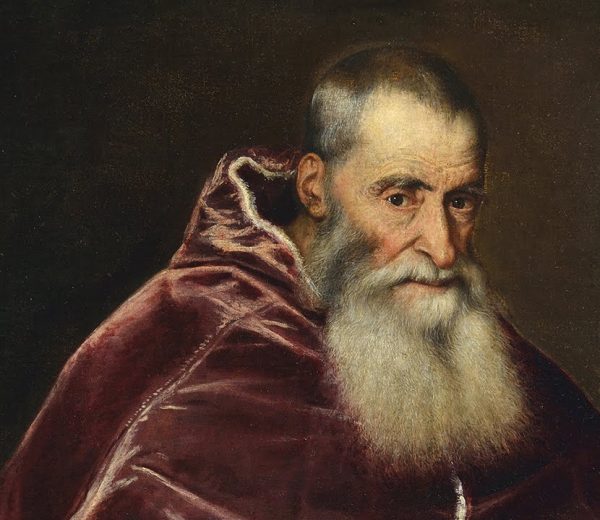

Titian, Pope Paul III, 1543. Oil on canvas, 44 3/4 × 34 15/16 in. Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

Flesh & Blood also has strong and interesting works by artists as varied as Lorenzo de Credi, Raphael, Lorenzo Lotto, Sebastiano del Piombo, Moretto da Brescia, Agostino Carraci, Guido Reni, Giovanni Lanfranco, Bartolomeo Schedoni, Simon Vouet, and Matthias Stom. Not surprisingly, the Neapolitan School is strongly represented by a number of artists who are little known on these shores, and who are generally represented in U.S. collections by lesser works. In addition to Ribera (mentioned above), Flesh & Blood features a complex masterpiece by Battistello Caracciolo and vigorous works by Massimo Stanzione, Bernardo Cavallino, a student of Ribera known as the Master of the Annunciation to the Shepherds, and the fascinating still life painter Giovan Battista Recco. The sole sour note for me is the disappointing painting Venus, Mars, and Cupid (c. 1670) by the estimable Neapolitan artist Luca Giordano, who made extraordinary paintings in Ribera’s style before going his own way. Indeed, the most astonishing, jaw-dropping pairing in the Capodimonte Museum consists of the versions of Apollo and Marsyas by Ribera (c. 1652) and Giordano (c. 1657). These two paintings were unavailable for Flesh and Blood because they were lent to the Giordano retrospective in Paris.

The Capodimonte is one of Italy’s largest — though somewhat under-rated and under-visited — museums. The 41 paintings (and one small bronze by Giovanni da Bologna) in this exhibition did not denude the Capodimonte of its highlights, which include additional masterpieces by Titian, Raphael, Lotto, Parmigianino, Ribera, and Giordano. Other highlights include stunning works by the likes of Simone Martini, Masaccio, Andrea Mantegna, Giovanni Bellini, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, and Correggio. Some Italians have criticized the exhibition for lacking the scholarly rationale worthy of the loan of so many precious works, though Flesh & Blood has a catalogue and an exemplary series of exhibition videos drawn from the opening scholarly symposium. (Click here for the complete playlist.)

The exhibition was co-organized by the Capodimonte, the Kimbell Art Museum, the Seattle Art Museum, and MondoMostre. I recently spoke by phone with Guillaume Kientz, the curator-in-charge at the Kimbell, who moved from the Louvre to the Kimbell in 2019. He is thrilled that the exhibition is reopening to the public, “giving the community access to all these great paintings.” He emphasizes the “striking scale” of the exhibited paintings, which are larger than most European paintings found in U.S. museums, including the Kimbell. Kientz thinks that the biggest revelations for visitors might be Caravaggio and Parmagianino, who, though “well-known by name,” pack an unexpected wallop in the flesh.

Flesh & Blood is drawn from the Capodimonte Museum’s two stellar core collections. The first component is the illustrious collection of the Farnese family. Alessandro Farnese (1468-1549) advanced the family’s fortunes by climbing the papal ladder. Pope Alexander IV made him treasurer and then cardinal deacon. Pope Julius II made him bishop of Parma in 1509. Alessandro catapulted his family into the highest social rank when he became Pope Paul III. As pope (1534-1549), he raised nepotism to an art form, stirring controversy when he made two of his teenaged grandchildren cardinals (popes usually extended this familial boon no further than nephews). Farnese power and wealth produced a remarkable collection of Renaissance and Mannerist paintings, as well as one of the world’s finest collections of classical sculpture (the latter is now mostly in the Naples Archaeology Museum).

Naples (which included a large portion of what is now Southern Italy) was a Spanish possession for centuries. Antonio Farnese, Duke of Parma, died in 1731 without heirs. The Farnese art collection passed to Charles of Bourbon (1716-1788) through his mother, Elisabeth Farnese (1692-1766), who was Spain’s Queen consort. Charles, who was installed as King of Naples in 1734, brought the collection to Naples in 1735. He started construction of the Capodimonte palace in 1738 and had the collection installed by 1759, when he moved to Madrid, where he was crowned Charles III, King of Spain. Charles’ successor in Naples, Ferdinand IV of Naples (1751-1825), began collecting local Baroque paintings. Naples was very cosmopolitan, and, after Paris, the most populous city in Europe. The arts flourished during the Baroque, in large part because of the renovation of Naples’ numerous churches, which began in the late 16th century. During the French occupation (1806-1818), religious art from suppressed monasteries joined the Bourbon collections.

Renaissance and Mannerism

For a short video tour of the exhibition, see here.

The exhibition commences with Titian’s portrait as its centerpiece. Rarely has an artist so clearly articulated power and dominance: this is a man who knew how to seize power, how to bend it to his will, and how to create a dynasty. Paul III is aged but not frail, as evinced by his furrowed brow, penetrating gaze, and, above all, by his mighty, ringed hand, which glistens as it emerges from folds of billowing fabric. This hand of power is worthy of a Roman emperor or a conquering general. Titian conveys the notion that it might be a good idea to bend over and kiss that ring — if you know what’s good for you. Paul III was a canny judge of artists: Titian’s portraits of the Farnese family would make an excellent exhibition. This painting inspired two of the most authoritative portraits of prelates by succeeding artists: El Greco’s Cardinal Niño de Guevara (c. 1600) and Velázquez’s Innocent X (1650).

Titian, Danaë, 1544–45. Oil on canvas, 34 15/16 x 44 3/4 in. Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

Alessandro Farnese, Paul III’s grandson, was just fourteen when he was made a cardinal. He commissioned this mythological painting from Titian, which he kept in his private quarters behind a curtain. Danaë, who is being impregnated by Zeus’ golden shower, is thought to have been modeled on the cardinal’s mistress, Angela.

Parmigianino, Antea, c. 1535. Oil on canvas, 53 9/16 x 33 7/8 in. Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

Antea is the name of a Renaissance courtesan, but the subject of this panting is likely an idealized beauty, rather than a specific courtesan or noblewoman. Parmigianino indulges his flair for anatomical distortion and his taste for sumptuous materials with highly varied textures.

Antea’s hands call attention to the costly materials at her midsection. Her left hand, which bears a pinkie ring, emerges from a heavily embroidered ruff and fingers her necklace, which is made up of chain links and cylinders spun from precious metals. This hand also rests upon a linen apron, whose texture is suggested by the weave of the canvas. Antea’s right hand is gloved in fine leather, and the stuffed marten head, whose fur she wears around her neck, appears to be biting her index finger through her glove. Antea creates this effect by manipulating the chain through the marten’s nose. Her shimmering, gold-brocaded sleeve creates further dynamic contrasts. The marten’s dangling right forelimb is nestled between her ruff and sleeve, as if it is struggling for traction to make its escape.

In this painting from five years later, Parmigianino moves — at least ostensibly — from luxury to civic virtue, with a heavy admixture of literal titillation. Raped by the son of Rome’s dictator, Lucretia had her father and husband swear revenge. Then she killed herself. The tyrant was driven away, leading to the founding of the Roman Republic. In many paintings that depict this theme (as with numerous Bathshebas, Deaths of Cleopatra, Penitent Magdalenes, etc.), eroticism is clearly a primary interest. Lucretia’s pale flesh shimmers against the black background, creating chiaroscuro effects that exceed that of most Baroque paintings. Since the artist died the year this painting was made, one has to wonder how the future of art would have been impacted if he had continued in this vein. The painting is a marvel of tonal and colored gradations of flesh, from the pearly highlights at the base of the neck through the blue-gray shadows, to her orange-flushed face. Every detail — and every transition between details — is brilliantly painted, including the patch of blond hair that bursts into curls above the ear, some of which are individually painted, hair by hair. Two rows of what seem to be perfect braids cross her head, echoed by two strands of pearls. There are individual wayward hairs within the braids. The pearls have glistening white highlights, and a considerable amount of blue, which sets them apart from the blond hair. Lucretia’s elaborate coiffeur extends a distance behind her head, though it is almost lost in the deep shadow that envelops it. Tiny, granulated gold threads that are woven into her hair are more readily visible, though they are distorted by the light that they reflect (an effect familiar from Vermeer). Lucretia’s body is beautifully rendered, albeit with an unnaturally long neck and tiny head. This pale body, painted without visible brush strokes, invokes classical sculpture.

Her toga, on the other hand, virtually screams: “I am made of paint.” The prominent hatchings and highlights are unblended, openly declaring their painterly materiality. The medallion has the same character, largely produced with brilliant highlights (the emerald and amethyst inlays are more fussily painted). These highlights create the unmistakable form of Diana the Huntress, the virgin goddess whose purity Christians analogized to that of the Virgin Mary. Lucretia, with her Heaven-ward gaze, would have been understood in a moralizing Christian context, subsisting in tension with the figure’s partial nudity and with Parmigianino’s evident delight in her naked flesh.

El Greco, Boy Blowing on an Ember, 1571–72. Oil on canvas, 23 13/16 × 19 7/8 in. Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

El Greco’s native Crete — where the artist began as an icon-style painter — was a Venetian possession. He moved to Venice in the 1560s to continue his education. The miniaturist Giulio Clovio (depicted by El Greco in a marvelous portrait in the exhibition) recommended him to Cardinal Farnese in November of 1570. The artist fell out of favor with the Farnese — perhaps because of his offer to repaint the Sistine Chapel in a “decent” manner (the Last Judgment was among the commissions Paul III had awarded to Michelangelo). The Clovio portrait and Boy Blowing on an Ember are thought to have been painted while the artist was lodged in the Farnese Palace in Rome. El Greco joined the Roman painters’ guild in 1572. Both pictures are rendered in an Italianate manner, as sober and precise as El Greco ever got.

El Greco was a bold, confident, and learned man. Boy Blowing is a manifestation of a classical ekphrasis (a verbal description of a work of art) by the Roman author Pliny the Elder. By creating his version of a boy illuminated by a faint fire that he stoked with his breath, El Greco contended with classical artists whose fame had outlived their most celebrated creations. This extraordinary work also points to a road not taken: El Greco could have become an important proto-Baroque realist. He instead became the creator of an ecstatic and expressionistic Mannerism. But his late style works because he had first mastered the naturalistic effects of nocturnal illumination, as in this painting. El Greco would go on to paint enormous, nocturnal altarpieces, illuminated by supernatural rather than natural light, but they are compelling — and “believable” — only because he could make them seem “real.” Two later, less naturalistic, firebrand-lit group pictures called Fábula (Prado and National Gallery of Scotland) can be viewed as transitional works between Boy Blowing and El Greco’s late works.

While El Greco eschewed the realistic detail, the quotidian colors, and the glowing ember found in this painting, he forever kept the bright light that began close at hand and had the power to blast through the eternal darkness of night. He reanimated the fantastic figural proportions he had learned in Crete; he refocused his blinding light on the brilliant colors he had discovered in Venetian painting; and he exceeded the dramatic gestures and facial expressions that he had witnessed on his path to Toledo. El Greco had no further need of flames and embers once his figures themselves became tongues of fire.

The Baroque

Annibale Carracci, Pietà, 1599–1600. Oil on canvas, 61 7/16 × 58 11/16 in. Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

This exhibition features three paintings by the Carracci. Pietà is an unusually classicizing work by the master due to its connection to Michelangelo’s sculpture in Saint Peter’s Basilica. In contrast to Renaissance paintings of this theme, Carracci decenters his protagonists: instead of a pyramidal configuration, he uses a scalene triangle. Rather than being cradled by Mary (a pose that forced Michelangelo to reduce Christ’s size relative to his mother), Carracci’s Christ reposes in part on the ground, while his head and shoulders rest on her lap. His corpse forms a diagonal that stretches across the canvas. A note of eerie naturalism is introduced by Christ’s corporeal discoloration, which is particularly evident in his hands and feet. The former are partially clenched, apparently in the grip of rigor mortis. Mary gazes at Christ, who faces our direction with a peaceful countenance, as if he were sleeping. The putti mirror this exchange of looks on a smaller scale: the putto who lifts Christ’s dead left hand looks down at the putto in the far right. He, in turn, faces and gestures toward the spectator as he pokes his index finger on a thorn in Christ’s crown, sampling his passion for our empathetic benefit.

Caravaggio, The Flagellation of Christ, 1607. Oil on canvas, 118 in × 92 in. Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples, from the Church of San Domenico Maggiore, Naples (property of the Fondo Edifici di Culto del Ministero degli Interni)

Caravaggio’s Flagellation — a late addition to the exhibition — is quite a coup for the Kimbell. Only one Caravaggio altarpiece is in a U.S. collection (Cleveland Museum of Art) and it, too, originally came from Naples, via a Spanish viceroy. Caravaggio had to flee Rome (and the Papal states) when he killed Ranuccio Tommasoni in 1606. He spent seventeen months of his last four years in Naples, during 1606-7 and 1609-10. Caravaggio’s Seven Acts of Mercy, painted soon after his arrival, altered the course of painting in Naples. This imposing Flagellation was painted shortly thereafter.

Since Christ’s foster father Joseph was a carpenter, then this Jesus appears to have been a lumberjack. His Bunyanesque physique would have made him difficult to capture, had he resisted arrest. While Christ is presented as a passive exemplar of physical perfection, his standing tormentors have coarse features that violate classical norms. The man on the right seems to push off on Christ’s lower leg as he tightens the ropes that bind him to the column. His right arm and Christ’s flowing hair are cursorily sketched. Keith Christiansen, the John Pope-Hennessey Chairman of European Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, discusses Caravaggio’s loose, abbreviated painting techniques in his lecture “Caravaggio and Naples: Style and the Dynamics of the Market.” Christianson argues that Caravaggio’s techniques in this final period were efficient and expedient, as well as novel and expressive.

The ill-clothed, jug-eared brute on the left grabs a handful of Christ’s hair as he utters an angry scream that contorts his irregular face. Clutching a bundle of sticks in his right hand, he can’t wait to begin the flagellation. The younger man at the bottom of the painting wraps a rope around some sticks to create another torture implement. Scourging, which could be fatal, was a harsh punishment reserved for non-Romans. Since, according to the gospels, Christ was unable to carry his own cross to Golgatha, he presumably suffered a debilitating flagellation. We can surmise from Caravaggio’s dramatic composition that Christ will soon be assailed from all sides.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith and Holofernes (c. 1612-1617). Oil on canvas, 159 x 126 cm, Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

The best-known female artist of the seventeenth century, Artemisia Gentileschi was the first woman admitted to the Florentine academy. She garnered an international clientele with paintings that often featured self-portraits within Biblical and mythological subjects. This might be Gentileschi’s first history painting, and it is likely her first treatment of this theme. She portrays herself as Judith in the act of slaying the Assyrian general Holofernes, who was attacking her town. This subject has often been linked to Gentileschi’s biography: she was raped by Agostino Tassi in 1611 (women were so disempowered at this time that Tassi’s crime was taking Gentileschi’s virginity without marrying her). It has been argued that Gentileschi enacted a painted vengeance by killing — and symbolically castrating — a male oppressor. However, as Patrizia Cavazzini points out, the subject might have been chosen by a patron rather than by the artist. In any case, the painting responds to the sanguinary Judith painted a few years earlier by Caravaggio (illustrated below), as well as other contemporary works.

Gentileschi depicts a frenzied, mortal combat, which features a tangle of six arms. Her youthful maidservant is an indispensable accomplice: she bears down on Holofernes, who puts up a mighty struggle. Caravaggio’s Holofernes, by contrast, is seemingly caught by surprise: a simple chop is sufficient to dispatch him, necessitating no assistance from the elderly maiden, who is a mere witness and trophy-bagger. Gentileschi’s Judith, still wearing the fine gown she had donned in order to beguile and disarm her enemy, stands at a curious distance from her victim. More psychologically complex and conflicted than Caravaggio’s Judith, she seems to shrink back, while nonetheless maintaining a steely resolve. Gentileschi’s more dramatic psychological effects derive from this state of deadly struggle. Her Holofernes resists, so she has to hold his head down with her fully extended left arm. Since she cannot lop his head off with a single, mighty stroke, Judith is forced to use an awkward backhand grip to saw it off, as if slicing through a loaf of bread that’s attempting to leap off of a table. As the adage goes, a woman’s work is never done. (For more information on Gentileschi, see essays by Judith W. Mann, Elizabeth Cropper, and Patrizia Cavazzini in the Metropolitan Museum catalogue Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi (2001), which can be downloaded here.)

Caravaggio, Judith Beheading Holofernes, c. 1598-9 or 1602. Oil on canvas, 57 in × 77 in., Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica at Palazzo Barberini, Rome (not in exhibition; photo from Wikipedia)

Battistello Caracciolo, The Virgin of the Souls with Saints Clare and Francis, 1622–23. Oil on canvas, 114 3/16 × 80 11/16 in. Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples.

Caravaggio’s Seven Acts of Mercy (1607) — which features all seven acts in one painting — broke conventions. Caravaggio’s example helped to free Neapolitan artists to make their own stark, strange, and complex compositions, such as this one by Caracciolo. Fittingly, it is installed opposite Caravaggio’s Flagellation.

Jusepe de Ribera, Drunken Silenus, 1626. Oil on canvas, 72 13/16 × 90 3/16 in. Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

This naked, unshaven, fat and rustic Silenus is a déclassé companion (and the foster father) of the wine god Dionysus (that could be him in the upper right corner, though it resembles traditional depictions of Apollo, the torturer-murderer of the satyr Marsyus). A far-from-ideal reclining nude, Silenus can be regarded as a satiric commentary on the reclining beauty/goddess theme. Ribera’s foray into that genre is lost, but Titian’s Danaë serves as an example in this exhibition.

Of the many international artists who followed Caravaggio’s example, Ribera was the single best handler of paint. This skill is particularly evident in the thick impasto Ribera used to emulate the wizened skin of old men, as in the old faun who refills Silenus’s shell from a wineskin. Edward Payne notes: “As one ‘skin’ is being emptied, another is being filled.” Punningly, Silenus’s upraised arm reads like a funnel in this wineskin-to-wineskin transmission. The face of Pan (the horned satyr who fathered Silenus) is particularly expressive as he adorns Silenus’ head with leaves. One wishes Ribera had painted more of these delightful creatures.

The young faun in the upper left happily has his own cup, and even the braying ass (which prefigures Goya) vocally signals its approval, perhaps in the hope that Silenus will become too drunk to ride the poor beast. A number of Spanish and Italian artists excelled in making cheery, realistic genre paintings of “low” subjects. Ribera’s Clubfoot (1642), a depiction of a Neapolitan beggar now in the Louvre, is a prime example. Drunken Silenus is an interesting painting to compare to Los Borrachos (1628-9), Velázquez’s nearly contemporary low-brow bacchanal. These two great paintings will no doubt continue to spark reinterpretations.

Giovan Battista Recco, Still Life with Candles and a Goat’s Head, c. 1650. Oil on canvas, 52 x 72 ½ in. Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

I close with this rustic still life by Recco, whose work is as plentiful in Naples as it is rare in the U.S. The deep shadows and the silverware that extend over the ledge reflect other aspects of Caravaggio’s influence over Baroque artists.

Extended through August 2 at the newly reopened Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth. The catalogue ‘Flesh and Blood: Italian Masterpieces from the Capodimonte Museum’ ($30) features essays by Sylvain Bellenger, General Director of the Capodimonte, and James P. Anno and Christopher Bakke, who are Curatorial Fellows.

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator who believes no trip to Italy is complete without a visit to Naples.

4 comments

Wow! What a breadth of Old Master’s! Happy that a slice of Europe made its way to Texas since an Italian Grand Tour is unforseeable in this corona-climate. Gotta make a trip to DFW soon 😀

I hope you do, Caitlin. Many major traveling exhibitions have been delayed or cancelled, so who knows when an exhibition of this importance will make its way to Texas again.

Looks like a roadtrip is in order.

Happy trails, Mark.

By the way, I have received some questions about the fur in the Parmigianino on social media. I recommend the discussion of a similar fur in a painting by Moroni in the following video: Aimee Ng, “Truth and Fiction in Italian Renaissance Painting,” Frick Collection (starting at about 36:19 minutes). Curator Ng notes that it signifies wealth, chastity, and childbirth, and that such pelts were thought to attract fleas from the body.