Duccio di Buoninsegna, The Raising of Lazarus, Italian, 14th century, 1310–11. Tempera and gold on panel. Via the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth

As I write this, depending upon one’s inclinations, we are now in the midst of solstice ceremonies, feasts of gluttony surrounding the celebration of divinity made incarnate, or gift-giving geared at plying young children into taking upon themselves the mantle of American consumerism. (Someday they, too, might long for a Sub Zero or a Maserati.) What fascinates me most in this frenzy of shopping is the idea of incarnation in this, the most discarnate age in history. And this occurs despite the celebration of bodily parts that range from Kim Kardashian’s capacious caboose to Paris Hilton and her endless array of dolled-up selfies that outstrip any degree of self-adulation ever witnessed — or certainly ever recorded.

To make some sense of our current culture — or merely as an aid to meditating on the phenomenon of our “glamorous” times — I’ll reflect upon two works of art. One is at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth; I refer to the 14th-century work of Duccio di Buoninsegna (1248 – 1318), done in the Byzantine style and flaming with red, blue and gold.

You may already know the story. It depicts a narrative given to us in the eleventh chapter of John. There we learn that Lazarus, brother of Martha and Mary Magdalene, has fallen ill; in fact, he has been dead for four days and the women tell Christ the unseemly news, “… Lord, by now he stinketh… .” Despite the fact that his body is decaying, Lazarus is, in fact, resurrected, and his state is underscored by a figure next to the stony cave in which Lazarus is seen bound in cloth. Specifically, a man in yellow garments standing to the left of the tomb is pinching his nose because the smell of deteriorating flesh is so deeply displeasing.

Perhaps it’s appropriate to interject that I was raised in a family of lukewarm Presbyterians. I’m not a religious nut, but I do find these things interesting. I was educated by Catholics and schooled for a stint in Rome. Thus, I was taught to love Giotto, Duccio and more. I was also schooled in the idea of a divine “Word” that was made flesh. Eucharistic is the term used by the cap-“C” church, and it has interested me ever since I dropped acid in high school and had a gorgeous experience remarkably similar to what Aldous Huxley describes in his book The Doors of Perception. (This concludes perhaps too much introductory material.)

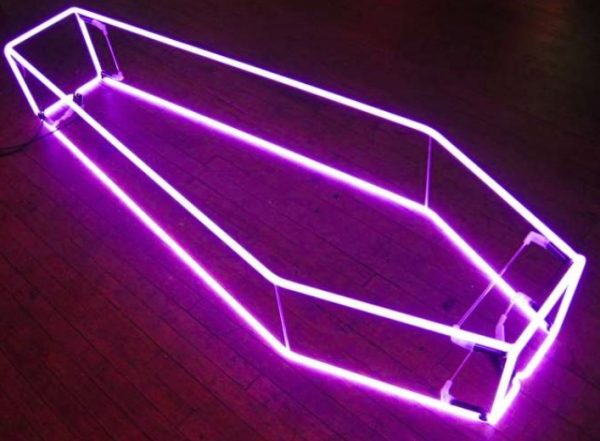

However, our cultural milieu readily comes into focus if we remember a piece by the YBA (Young British Artist), Sarah Lucas; it was long on display at the Goss-Michael Foundation in Dallas during its stint on Turtle Creek, and is still housed in its collection. Titled New Religion, it was constructed circa-1999 of violet neon tubing that creates an outline of a casket shape that contains nothing at all. What resides inside the piece is the same air circulating in and around it. And this, of course, is the same current of breathy stuff inflating our own lungs. Death and life eerily merge and the tomb is delineated by light — the very stuff we are told that the Creator wields with enormous velocity and heft. (The narrative of the Transfiguration is but one example among thousands.) But Ms. Lucas has made the light a genuine “gas.” It’s an engaging vector into thinking about what death meant in years past by virtue of showing us a contemporary outline of our discarnate world. Not a bad effort.

So what do we do with this backlog of cultural imagery? Maybe we’re urged to remember the luxury of silken garments and pigments wrought from ground lapis — or perhaps we’re urged to inhale and exhale with yogic vigilance and understand that the world is saturated with the sparkle and spangle of wafting O2. To quote my last bit of writing for Glasstire, perhaps it simply “is what it is” and, by and large, that’s pretty fascinating.

But it’s difficult to fail to marvel at the strangeness of a world in which sensuousness is worshipped with abandon and yet Duccio seems nearly bombastic by comparison. Even Magdalene herself was a lesson in extravagance. She broke a vial of perfume, purportedly of inestimable value, to bathe the feet of Christ before blotting the wet fragrance with her hair. Compare this to a photograph of Hilton in a bondage shot and holding a microphone provocatively. Which is richer? And how is our culture really faring in the “shot loose” department? Do we even know any longer how to truly come undone?

2 comments

Thank you for great questions to launch us into 2019.

Gwen, thank you for reading my article and thank you for your comment. It led me to reconsider my use of the word “story” with regard to the Lazarus narrative. It is not a story among stories. Rather, it has the sheen of truth and, along with all myths, it should be observed that “the myth is true.” Thank you again.