Para leer este artículo en español, por favor vaya aquí. To read this article in Spanish, please go here.

Maritza Bautista, Pedro Morales, Melissa Amici-Haynes, Gil Rocha, and Cande Aguilar in front of Rocha’s “Esto Cala” installation at the “Soy de Tejas” exhibit at Centro de Artes in San Antonio. Photo: Melissa Amici-Haynes.

When Gil Rocha was a curious Laredo teenager growing up in the 90s, his main outlet for viewing art was the International Bank of Commerce. He recalls a print by Salvador Dali hanging at the bank; those prints were “like free visual gold for me,” he says.

Aside from occasional student exhibits at the local colleges, the city had no art museum at the time. The Laredo Center for the Arts (LCA) was in its infancy, and the building that was previously a market and city hall throughout its 100-year history had just been converted. Performance art was no different. Veteran Laredo artists fondly remember Espumas — the only independent cafe in town in the early 2000s — a glimmer of hope for creatives with its small open-mic night. As is the story for many of the city’s short-lived art spaces, rapid economic growth erased Espumas to make way for a new overpass.

Today, Rocha both curates and exhibits his own art at galleries around the state and country. Currently he is co-curating a collaborative traveling project, The Border is a Weapon, which previously showed at the LCA and will reopen at Syracuse University in New York state this fall. In years past, an artist making moves like Rocha might spend their entire adulthood away from Laredo and only return for Thanksgiving and Christmas. But Rocha’s home and studio remains a few blocks north of downtown Laredo. And there is much more to that downtown today than wholesale perfume shops and warehouses advertising ropa usada.

In March of 2020, the U.S. banned all nonessential border traffic, immediately turning central Laredo into a ghost town with the instant loss of thousands of Mexican shoppers who crossed the bridge every day. Laredo’s budding downtown arts scene looked like one of the first victims of this shutdown. But instead of shriveling up, what emerged from the pandemic was like a hyper-adaptive huisache tree sprouting from a drought-plagued desert.

Laredo Center for the Arts Executive Director Rosie Santos with Eric Avery in front of a nipple wall installation by Avery. Photo: Ryan Cantu.

While the LCA remained dormant during the pandemic, board members like Melissa Amici-Haynes and Pedro Morales used the downtime to visit art exhibits outside of Texas. As they toured galleries in cities like San Antonio and Dallas-Fort Worth, they began noticing the consistent presence of Laredo-born artists doing great things everywhere else but Laredo. Cesar Martinez, a pioneer of Chicano art, exhibited from coast to coast and had work at Ruiz-Healy Art and the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio. Ethel Shipton’s archival prints of the vast highways of Texas were featured at the AT&T Center, the Spurs basketball stadium that countless Laredoans visit without a second thought to the art on the wall. Ana Laura Hernandez’s art was recently acquired by the collection at The University of Texas at San Antonio. Laredo artists aren’t just thriving across the Border Patrol Checkpoint, but they are also thriving across the Atlantic, where young artist Mauro Martinez had been picked up by the Unit London gallery.

“All these important artists were producing incredible work outside of Laredo, but there was not really a space for them here,” said Morales, who had spent several years as an architect and an abstract painter before joining the board of the LCA.

But then a lightbulb went off.

“Seeing all of these Laredo artists producing this great work outside of Laredo, we imagined a space in Laredo where pieces of each of these artists had a space and see how they interacted with each other.”

Melissa Amici-Haynes, who has been active on the LCA board since 2008, added that “we Laredoans often feel like an invisible population, but we are everywhere.” Her statement manifests not just in exhibits like those at Ruiz-Healy Art, but also by the ongoing Soy de Tejas exhibit at the Centro de Artes in San Antonio. This show hosts a little piece of the Laredo barrios near Rocha’s stomping grounds, with his work Esto Cala, a makeshift fence that is like a patchwork of found objections from the barrio: pallets, cardboard, a comical sign that advertises Se Vende Aire (“Air for Sale”).

As a young artist, Rocha was inspired by trailblazers like Cesar Martinez, who embodied that successful Laredo artist that seemed to be everywhere else. After a brief stint in the Army during the Vietnam War, Martinez came back to San Antonio in 1971 with state-of-the-art photography equipment and began using photography in service of the Chicano movement. Since then, he has become a landmark Chicano artist; color field abstracts in his Serape series were just acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

“But in Laredo, there was a whole new generation that didn’t know who Cesar was,” Morales says. “The idea was to make connections with these artists and reintroduce them to the community.”

“We had several artists on the board who were really helping us change how we were doing things,” says Amici-Haynes. “What we wanted to do is set a bar for artists and how their work would be respected. Part of that was purchasing their work rather than asking them to donate as we had in the past.”

The LCA’s Exhibition Review Committee formed an Art Acquisition Project that began creating a “wishlist” of a dozen or so successful Laredo artists that could be part of this effort, then created a catalog to compile some of their key works that the LCA might eventually showcase and even purchase. The list has since doubled in size.

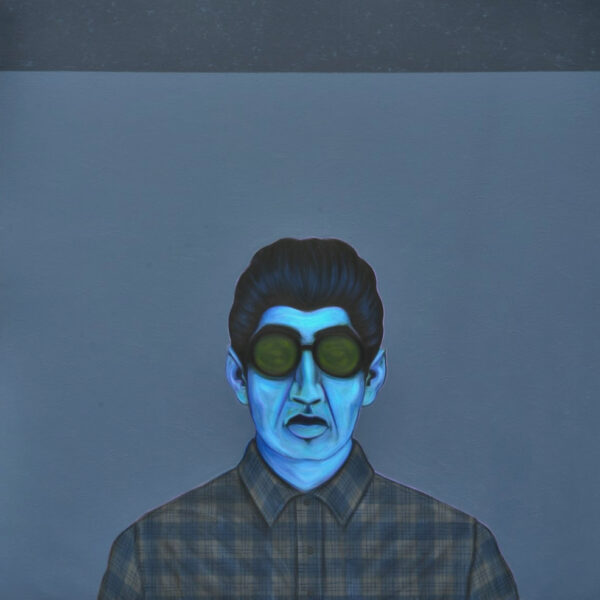

The Committee pitched its ideas to the LCA’s board at large and convinced the board to jumpstart the project by purchasing two works: Blue Bato con Sunglasses by Cesar Martinez and La Frontera by Ethel Shipton.

Ethel Shipton and Gil Rocha in front of “La Frontera” by Shipton: 2021, archival print on Hahnemuhle paper, 30 x 40 inches. Photo: Gil Rocha.

Cesar Martinez was one of the first exhibits that was part of the LCA’s new initiative. He was floored by the tremendous reception he received upon his return to Laredo, from receiving a key to the city by Mayor Pete Saenz to a loud welcome by the Tigerettes dance team and mariachi band from Martin High School, his alma mater.

According to Amici-Haynes, his visit to Martin High School gave immeasurable inspiration to many of its students who come from some of the poorest parts of Laredo. “There is this misconception that art is for the elite. But when you start to showcase people who have names like you and look like you, you realize that art is for you too,” she said.

Martinez, now in his 70s, agreed that there had been a lack of creative outlets for emerging artists throughout much of his life, which caused many to leave in search of more nurturing places. But today, Martinez agrees that “there is an influential cadre of progressive-minded cultural activists operating in Laredo, and that is the reason for the current surge of activity. It always takes somebody to make it happen.”

The acquisition project also reconnected the LCA to members of the small artist enclave in nearby San Ygnacio, which has been spearheaded by artist and activist Michael Tracy since the 1980’s. Shortly after beginning the acquisition project, LCA members were introduced to Eric Avery, a retired doctor who had recently established his home and studio in the town.

Avery’s exhibit, Eric Avery, M.D., Art as Medicine, was the most recent that just closed at the LCA in early May. Among Avery’s woodcut prints and medical-themed artwork, the exhibit had provocative images like a full wall installation of giant gray nipples, a “glory hole” through a Renaissance print of Adam and Even, in which you could see a print of Donald Trump’s angry face, and a wallpaper print illustrating how to use female condoms. The wallpaper caused a controversy in Houston in the 1990s when the vice police tore it down after a parent complained.

I asked Avery if his exhibit had faced any pushback from the heavily Catholic and culturally conservative community of Laredo. To the contrary, Avery told me that the LCA is almost like a blank slate that is giving these newly returned artists full creative license to set up their exhibits. “There’s no curator telling you what you can and can’t do here,” he said as he discussed how members of the LCA were fully cooperative in helping him realize his vision for the exhibit.

“It helped that he was a respected medical doctor,” added Rosie Santos, the Executive Director of the LCA.

The organization acquired Avery’s print Stash House, which also hangs in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the British Museum. The piece — a somber tribute to the desperate migrants who quietly flow through the area — is the newest addition to the LCA’s small but growing permanent collection of works which is currently installed on the organizations upper mezzanine floor. As Amici-Haynes recalls Cesar Martinez saying, “a collection is a down payment on a museum.” That’s the goal of this collection: to one day build a separate contemporary arts museum that focuses on important Laredo and regional artists. With all the buzz orbiting around the LCA — not just with a surge of visiting regional artists but with the success of newer nonprofit groups like artist incubator and residency Cultivarte — a Laredo Contemporary Arts Museum is no longer a pipe dream.

Angel Cabrales’ installation “Naciones Unidas de Anahuac,” 2019, with the artist’s Pan-droid multimedia installation in background at the Laredo Center for the Arts.

Laredo has long been a major interchange between Mexico and the United States. Perhaps because the city could always look either north or south for its culture and prosperity, it was easy to neglect the in-between frontera culture that existed right here on the border. But Laredo was forced to look in the mirror and embrace itself after southbound tourism shut down around 2007 because of a spike in cartel violence in Mexico, and also when northbound tourism shut down with the pandemic. “Back then, there just wasn’t a lot of focus on our culture, because our culture was in Nuevo Laredo. But of course, having that shut down, Laredo had to reinvent itself,” says Shipton.

“But no matter where you end up, Laredo always feeds you,” she said. “It certainly guides me in my work all the time.”

The success of Cesar Martinez’s exhibit and its Chicano and indigenous themes is also testament to Laredo’s recent introspection. “The Chicano Movement was everywhere,” Martinez says. “But I don’t remember it being significantly embraced in Laredo. As one of Texas’ earliest settlements, Laredo developed a somewhat aristocratic elite that, as time went by, became a matter of haves and have-nots. As a have-not, the only kind of discrimination I ever felt in Laredo was classist discrimination.”

But Martinez noticed a change during his 2021 homecoming, with a diverse arts scene that was much more inclusive and democratic than years past. “The same thing has already happened in El Paso, and I finally see it happening in the Rio Grande Valley and especially Brownsville. This is partly a product of the times we are living in; there are few places that the internet doesn’t reach. Since my show, En Mi Casa, I’ve seen a surge of significant, challenging exhibitions there by local and regional artists who have exhibited at the national level.”

As Martinez observed, Laredo’s artistic sea change is rippling far beyond this little corner of South Texas and is attracting artists from both poles of the 1,200-mile border with Mexico. A recent exhibit at the LCA hosted Brownsville-based artist Cande Aguilar for his exhibit BarrioPOP, which included a long indoor mural with tributes to Tejano culture, including nods to the region’s street vendors and the conjunto accordion music.

The LCA’s current exhibit, Dis/U Topia: Futuros del Pasado y Presente, features Angel Cabrales of El Paso. The show is a merger of two of his exhibitions, It Came from Beyond the Border and Uncolonized. Both Cabrales and Aguilar have works at the Soy de Tejas exhibit, along with Rocha.

Cabrales knew little about his Rarámuri indigenous heritage growing up. As many people from the Southwest can relate, he tells me that his family suppressed this background out of shame, leaving him to uncover his own history from scratch. Recently, he has used his installation pieces to highlight the tremendous cultural and technological achievements of the indigenous groups of Mesoamerica. With his sci-fi reimaginings of indigenous figures, his goal is to disarm his viewers and immerse them in his exhibits before they might be repelled by the anti-colonial themes of his work.

When Cabrales took our group through his exhibit on its opening weekend, he began by pointing to print movie posters for a series It Came from Beyond the Border. Flying saucers are replaced by concha sweet breads. As Cabrales explains it, this motif reflects the contradictory way that Americans embrace Mexican culture like food and tequila while the country shuts its doors to the people who bring it. Those shut doors are represented by the militaristic metal grates and fences he superimposes on wholesome American objects, like the playground installed at Soy de Tejas or his piece at the LCA called Five Lights, an Orwellian American flag guarded by diagonal metal grates. A row of four floodlight lines sits above the flag. Below is a line of boxes of actual lost or abandoned objects recovered from migrants.

The second part of his exhibit, Uncolonized, is a utopian vision of what the Americas could have looked like without the European conquest. Rather than employing the tired trope that extraterrestrials must be the only explanation for ancient wonders like the Mayan pyramids, Cabrales’ exhibit pays tribute to the significant technological advancement of indigenous people before the Spaniards arrived with figurines like his Zapotec-nical Engineer. His bash-kit sculpture of a piñata reconstructed from a model spaceship looks like it could be the robotic pet of an enlightened Darth Vader.

As Cabrales’ show is on view, artists no longer have to tiptoe around taboo words like Chicano like they did during Cesar Martinez’s early years in Laredo. Instead, a new generation is paying tribute to the past while building bridges in new creative spaces that span the border. Laredoans are realizing that building bridges is easier than it seems in this rare border city without a wall.

Angel Cabrales’ exhibition Dis/U Topia: Futuros del Pasado y Presente opened at the Laredo Center for the Arts on June 2, 2023 and will be on view through August 4, 2023. The Laredo Center for the Arts’ Exhibition Review Committee consists of the following members: Melissa Amici-Haynes, MaryAnn Garcia, Gil Rocha, Jessica Diez-Barroso, Julio Mendez, Eva Soliz, Pedro Morales, and Amelia Ramirez.

1 comment

Wow! Wonderful Article you have featured here. Once again, grasping the integrity of our vision for the Laredo Center for the Arts primary goal, recognizing exploring and further educating our community in the importance of Art. Thank you!