A sculpture with a piñata head of Sheriff Woody from the Toy Story series sits at the entrance of Cande Aguilar’s solo exhibition at grayDUCK Gallery in Austin. The head is a rough, somewhat unfinished papier-mâché ‘knock-off of the original’ version, and it tops a totem of a sculpture. The base of the sculpture is a classical white plinth spray-painted black, pink, purple, and blue in an unfinished series of erratic gestures with bits of the original white peeking through. On top of the plinth sits an art history textbook; on top of the book sits half a globe; and on top of the curved part of the globe is the piñata head of the papier-mâché ‘knock-off’ version of Sheriff Woody’s head.

And it’s the perfect entry piece to Aguilar’s solo exhibition. Titled It’s Only BarrioPOP but I like it, the show opens viewers to the world of Cande Aguilar — a world that is the vernacular of the South Texas border meeting a white-cube gallery, which is an odd juxtaposition of space, place, references and a quotidian baroque in a pristine setting. It’s an unconventional mismatch that works, and in terms of the commercial art world in general, Aguilar has blazed a trail into the white-cube space that has long overlooked the conversations and images of the Mexican American vernacular.

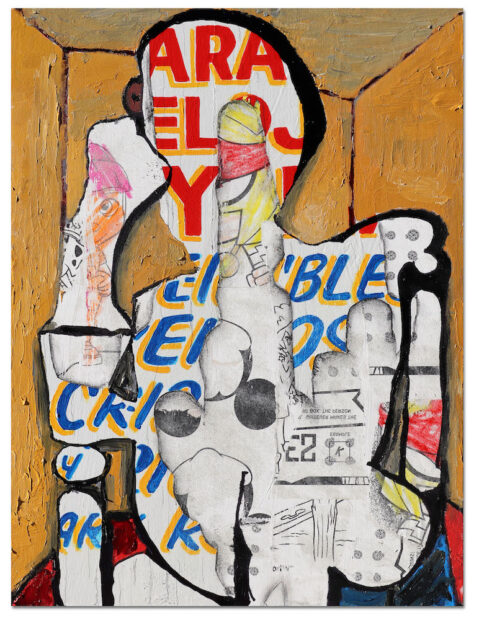

In Aguilar’s hands, the world is “BarrioPOP.” It’s a mix of aesthetic messages taken from the Pop Art movement in art history — one that turned to identifiable imagery from popular culture — with a twist of visual and actual language that is specifically barrio. Translated literally as ‘the neighborhood,’ the barrio refers to the contexts of Mexican American neighborhoods, or specifically the Mexican American, Rio Grande Valley inventiveness of creating the most from the least, of reviving common objects for uncommon uses which might, at times be crude — but crude doesn’t matter if it functions and grabs the eye. In Aguilar’s hands, the visual language of Pop is not just the elevation of commonplace objects or imagery; it is specific to the language of the border and border culture, a mix of both United States and Mexico, of both places at once — just like what life on the border really is.

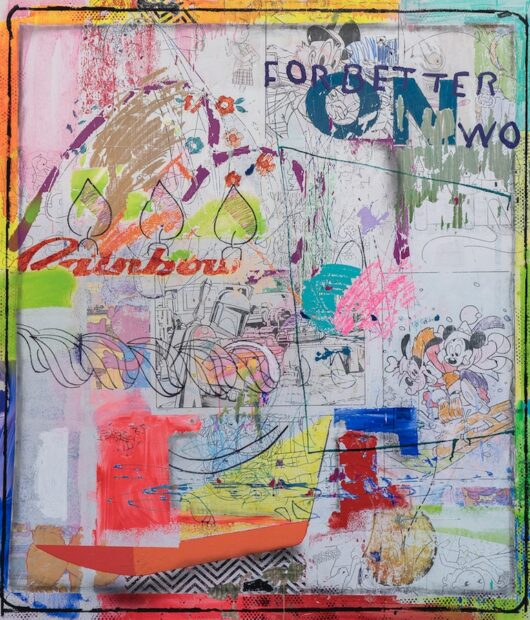

The result is a show full of paintings that pull from art historical references with a smart, tongue-in-cheek irreverence. El Verde, 2020, a large scale, mixed-media painting on panel has layer upon layer of transfer through which Western cartoon characters, such as the legs of Winnie the Pooh, share the field with El Veneno Verde, the famous Mexican wrestler. Because along the border, both exist equally, and both contribute to a culture that is visually and referentially of both.

In Aguilar’s work, layers of images are both applied and scratched away; pochismos or Spanglish words from repurposed business signs are framed in ornate, gilded frames. Mickey Mouse, Goofy, and Big Bird are collaged into panels with loteria cards. The logo from the former Rainbow clothing store in downtown Brownsville holds a prominent place in on work titled For Better or for Worse; a painting akin to Picasso’s Sunflowers receives its own technicolor spin. This is not the Pop Art of Art History. This is the Pop Art of Brownsville, Texas — an enigmatic, idiosyncratic place few understand, but where many live. It is a language of mixes, of clashes, and of coexistences, and Aguilar’s exhibition presents yet another clash and coexistence — that of the language of the border finally holding the place it deserves in the space of a white cube gallery.

Through May 23 at grayDUCK Gallery, Austin.