Para leer este artículo en español, por favor vaya aquí. To read this article in Spanish, please go here.

Laredo is always coming, going, and shifting, making the sense of time work differently in this place. What I recall from my first visit to the city, for instance, is that the time of day transforms one’s experience so completely, as though you are transported to a place across the world. A series of shuttered, dry, and beige stucco buildings along downtown turns into a night walk with new friends, which follows the zigzagging Christmas lights across tree branches in January on San Agustin Avenue. Stepping into an evening bar, with no signage and chains across the door handles, puts on a lens of the cinematic and baroque, with dim, smoky lights over shots of Dobel tequila and gin and tonic, accompanied by the gentle, indistinguishable flows of the fast, dissolving rhythm of a local Spanish dialect and English, dotted with occasional waves of laughter.

If this glimpse contains an element of the real thing, and if what the local folks say is true, Laredo is a city of transformations, transactions, and extremes. The largest inland port along the U.S.-Mexico border, present-day Laredo still bears the marks left by NAFTA — after the treaty was signed in 1993, the related monetary policy of Mexico led to the devaluation of the peso in 1994, slashing its value by half. The subsequent bleaching of jobs and the loss of Mexican consumers then led to an unemployment rate of 17.7% in Laredo at the time, devastating the local economy. Today, walking through its downtown, Laredo is full of shuttered buildings and closed storefronts — empty real estate everywhere you look.

Right now, artists are envisioning what Laredo’s transformative — yet stark — landscape could become. There are a few possibilities, like whether Laredo could host new types of experiential artworks for the public in its historic spaces, or whether Laredo could be the next Detroit: a major post-industrial port city with lots of empty real estate.

These dreams are on their way to becoming reality, thanks in large part to artist-run initiatives in the city, and the city’s engaged support. A key organization in this shift is Cultivarte Laredo, which was recently founded and is run by artists in Laredo who are trying to breathe new life into its downtown area. Cultivarte Laredo brings artists together, connecting them with the city’s cultural funding, as well as with institutions like Laredo College and Laredo Center for the Arts.

The Organization

Cultivarte Laredo was first founded in 2019 by two of its current board members, Alyssa Cigarroa and Regina Portillo. In addition to remaining on the board of Cultivarte Laredo as its president, Cigarroa is now also a city council member for District 8, after winning the seat in 2020 as a write-in candidate.

The city’s cultural organizations were granted new life with Cultivarte Laredo’s founding, as Cigarroa and Portillo lobbied the city to dedicate 2% of its annual revenue toward arts programming under a new Arts Master Plan. They were successful, and the first grantees of this money were artists working on public works projects, particularly murals. However, the distribution of funds was given to district’s council members, who had direct control over the commissions for their district. Artists once again lobbied for a better system of funding the arts, and Cultivarte’s current funding and support came out of this effort, currently under the auspices of its parent, the Daphne Art Foundation.

Maritza Bautista is Cultivarte Laredo’s Executive Director, and stepped into the role in early 2020, as programming was set to start just before the beginning of the pandemic. Unable to proceed with existing models of art organizations, Bautista decided on a virtual artist residency program. Currently in its second year, the virtual V-AiR artists-in-residents are based in Laredo, as well as elsewhere in Texas — places like San Antonio, Houston, and Mission — so long as they have ties to the city. It is a 3-month online remote residency with a stipend, and there are four artists in its 2022 cohort: Diego Canales, Karla Gabriela De La Fuente, Erika Ordoñez, and Itzel Vilches. In 2022, in partnership with Laredo Center for the Arts, Cultivarte established the new C-Studio Residency, which is a pilot 3-month in-person residency program.

In addition to this pilot studio residency, Cultivarte Laredo is currently expanding its operations to a much larger scale. The next phases of its development include its first featured artists exhibition, Reflective Fluctuations, and its second show overall, which will be at Laredo College. The organization is in the midst of establishing an office at Laredo College, as the college’s art department and Cultivarte Laredo look to develop a cross-institutional dialog connecting local artists with higher education resources. The biggest upcoming change is that the organization has a new home, which will be leased to Daphne Art Foundation for Cultivarte Laredo: a privately owned older building, which is set to begin major renovations starting later this year. This new space for Cultivarte Laredo has 5,000 square feet of operating space, which includes plans for exhibition space, artist studios, a resource library, a café with patio, and a fabrication shop. This new home is set to change the essence of the organization.

This is all happening within a supportive arts environment — case in point, an art collection, funded by the community and other sources, will now be housed at the Laredo Center for the Arts; this is a major investment for the past and the future of art in the city. Cultivarte Laredo is representative of this vision for a lasting transformation in an ongoing collaborative effort between art, government, and people.

The Studio Residency

I recently had a chance to visit Cultivarte Laredo’s C-Studio residency program taking place at the Laredo Center for the Arts. Over the past months, the Center has been providing studio spaces for two artists-in-residence, Nansi Guevara and Nestor.

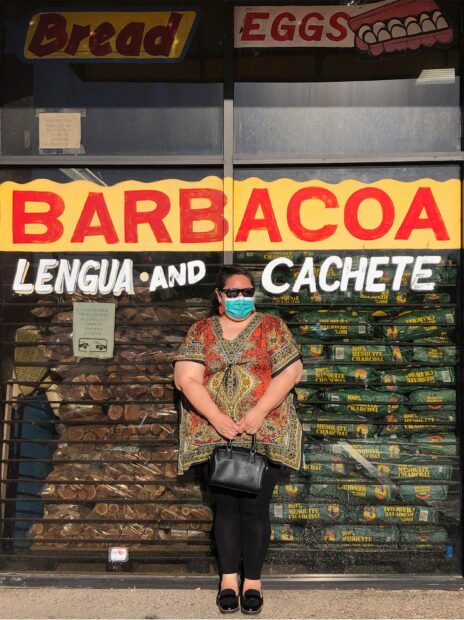

Nansi Guevara is an artist and an activist based between Laredo and Brownsville. Her work celebrates the deep and complex culture between borders in South Texas using various media, including textiles, prints, mixed-media installations, illustrations, and children’s books. She was raised in Laredo. After obtaining her undergraduate degree in Fine Arts Design at UT Austin and her Master’s in Education from Harvard University, she returned to the fold of South Texas and started making work about the communities and the cultures in the region.

With the residency coming to a close at the time of my visit, I was not able to see Guevara’s work in person, but instead we discussed her overall practice. During her C-Studio residency, Guevara documented her mother’s life. Guevara’s mother took on various labor-intensive jobs while raising her children. Near Camargo, Guevara’s grandfather picked cotton, the historic economic staple at the border region between Texas and Tamaulipas, Mexico. With her mother’s generation— before NAFTA moved the industry further south — the family’s link to cotton continued with her mother’s work at a garment factory in Laredo. Her mother’s history is representative of the history of women’s working-class labor in this area. The region’s residents have often taken on cross-border opportunities between Nuevo Laredo and Laredo, as part of a national fluidity that is common here and informs the specificity of its eclectic mixing of cultures.

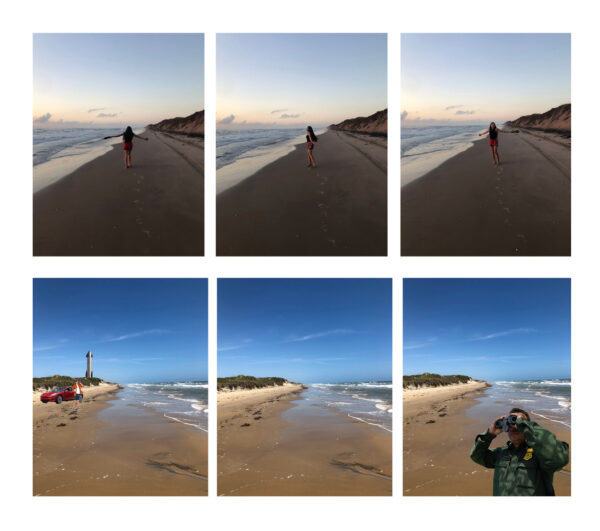

Another ongoing project for Guevara is a series condemning the negative environmental and social impact of the incoming SpaceX program at the Boca Chica Beach, near Brownsville. Guevara draws a parallel between the current ongoing redevelopment of the local residential community known as Boca Chica Village and the history of a 1920s redevelopment program for Boca Chica’s residential community known as Magic Valley. From her historical research, she compares the idealistic interwar period branding of this residential community as a home for the regional industrial labor force, and the visual impact of the new redevelopment at the community that is happening now. Guevara’s work prompts South Texans to challenge developers who are currently buying and flipping the real estate at the site. In this process, they’re imposing a monolithic identity on the region, repainting each turned unit in a white and gray color scheme reminiscent of spaceships to appease the influx of SpaceX employees.

Guevara also has an upcoming publication, a children’s book normalizing and celebrating the Spanglish commonly spoken in Texas’ border region. From my personal experience as an educator in the region, there is a cultural pride in this dialect that is unique to South Texas, and there is also a level of cultural complexity associated with it, particularly when it comes to an official use, or in the context of native Mexicans. Guevara’s work would be an uplifting reference for children growing up in bilingual South Texas, empowering them to embrace their bicultural heritage.

Nestor’s project from the C-Studio residency comes from another end of an artistic spectrum. The work consists of several groupings of assemblage objects, carefully collected from various contexts throughout Laredo and placed on top of a large rectangular mirror tabletop. Each of these groupings represents a short story that unfolds visually. For instance, one grouping is a three-level stacked structure of mirrors, metal and glass, seated tightly inside a circular candle stand with six outstretched holders that alternate between real and fake white candles.

This assemblage reminded me of my January visit to Laredo — the magic-like transformation that occurs depending on the time of day, and the differences between reality and appearances. The protagonist in Nestor’s story is a tiny white plastic toy baby that sits oddly between the layers, like from inside a rosca de reyes magos, bound helplessly to a wire spring and placed inside a small plastic gold cap. A new visitor to Laredo may relate to the funny disorientation described by this small figure, tied down and along for the ride. At the very top of this tall arrangement is an empty gold lattice-patterned cap that once held a lightbulb. Nestor took the time during my visit to open this up to reveal what is inside — stacks of remarkably uncanny and detailed plastic toy coins. What better describes the hidden and arbitrary economic and cultural forces that form the engine of activity and exchange within this border town?

The whole arrangement will eventually sit inside the ticket booth of a shuttered historic movie theater in downtown Laredo for a site-specific intervention set to take place this autumn. It is a work that will reanimate a symbolic architectural landmark; this theater was once the focal point of gathering and entertainment downtown. Joining this piece will be printed photographs of some of these groupings of objects, printed on the thinnest organza, or veil, and superimposed over velvet printed with rainbow-colored rings.

The materials speak once again to magic and appearances, as well as the history of garment manufacturing that once took place in Laredo. These fabric pieces will be placed inside the four poster display cases on the building façade. The work overall will be installed and lighted, with music from old movie soundtracks playing during the intervention. In its essence, it will be a work alternating between the abandoned present of Laredo’s downtown, much of which stands empty, and the fond memories of its heyday, before NAFTA and the crash of the Mexican peso.

Nestor is the name that artist Noé Cuéllar uses when making solo work; his practice additionally encompasses writing and sound art. He collaborates with Joseph Kramer as Coppice, formed in Chicago, to create music and rhythms using broken instruments exhaling air, and static sounds passing through hacked and reconfigured cassette tapes. Cuéllar spent his younger years in Laredo, and then, like Bautista, attended The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He too has recently moved back to Laredo. Like a number of other artists involved with Cultivarte Laredo, including his colleague Guevara, Cuéllar’s work reimagines the meanings of borders and identities, launching histories and experiences toward new, reconfigured possibilities.

The Exhibition

Cultivarte Laredo’s recent Reflective Fluctuations exhibition was comprised of the work of Cultivarte Laredo featured artists, including Allan Gindic, Carlos Grajeda, Noël Heller, Shellee Laurent, Lizett Montiel, Pedro Morales, and Cristina Zorrilla Speer. The show, which closed on August 11, took place at the Martha Fenstermaker Visual Arts Gallery at Laredo College, and was curated by Bautista. Following the first exhibition, the 2021 V-AiR Exhibition that took place at Gallery 201, Cultivarte Laredo’s recent show worked to expand the curatorial complexity and scope resulting from the organization’s growing efforts.

Exhibition view, “Reflective Fluctuations,” Allan Gindic, Carlos Grajeda, Noël Heller, Shellee Laurent, Lizett Montiel, Pedro Morales, and Cristina Zorrilla Speer, on view at the Martha Fenstermaker Visual Arts Gallery at Laredo College

Shellee Laurent’s Fuera de la ceniza/Me levanto con el pelo rojo y como hombres como aire (2022) is a self-portrait, a fleshy mass in pink and fuchsia that rolls outward toward purple edges, with the head outside of its frame. The figure leans against a guardrail on either side, like a crucifixion, with its arms also cropped out of the picture plane. The work reveals the powerful presence of an indigenous woman pushed against a barrier at the border, accentuating the epidermal inclines and valleys of her nude body as a receptacle and surviving crucible of colonial violence. This is an experience shared by many women living in the South Texas region.

Pedro Morales’s Luna Llena (2021) is made up of found washer and dryer parts. Foremost of the assemblage is an aged white casing for a front load dryer. Strips of reflective tape with a honeycomb pattern are lined up together, covering a black backing the casing is screwed into. The round opening of the dryer cover reveals this wall of reflective tape. The work transforms instantaneously when one aims their camera or phone at it to take a flash picture, as the work in the resulting image glows like the moon — hence the title, which means “full moon.” Brilliant, funky, and celestial, the work embodies rasquachismo, the DIY aesthetics of Laredo and the border region, with an interest in pop irony and the sublime.

Lizett Montiel is a multi-disciplinary artist with a foundation in dance. She currently also DJs under the name Rizu X, spinning at various electronica events, venues, and festivals in and around the border region. For this show, she presents Parajes (2022), a single-channel video of glitchy meltdowns dissolving a series of urban landscapes, set to pulsing music, with the busy, divided, diffused, and topsy-turvyness of Laredo’s border sprawl playing out across the screen. Colors meld and objects move and beat along with the music, made up of different tracks of drum and bass and house and techno mix.

A large multilayered painting in the show, Whisper (2016), depicts a single, highly detailed and fabric-like feather. The artist, Cristina Zorrilla Speer, has been active between the border regions over many years. Thin wisps of brown, yellow, and tan swirls float, as though the feather is taking on air, against a silver and gray background. Black highlights help the surface move like a quiet and steady campfire flame on a good piece of charred wood. A native Mexican artist now living in Texas, Speer has shown her work across both sides of the border over the past three decades, and represents the binational identity that is characteristic of Laredo.

The exhibition spoke to the complexity of the melding influences that make up Laredo, and the complex multicultural history shared by Texas overall, particularly between indigenous, colonial Spanish, Mexican, and other European colonial histories. With this show, Cultivarte Laredo marked the auspicious launch of its second phase of development, which involves shifting its operations from the virtual to the physical, and portends the exciting things to come out of this transformative, magical place: Laredo.

3 comments

Wonderful article on what is happening here in Laredo as it relates to art and artists and how import Cultivarte is to that growth. One minor correction, the collection at the Center is not funded by the City of Laredo, would be amazing if it was, however at this time it is made possible by contributions from the community, and fundraising efforts by the Art Acquisition Project and the Laredo Center for the Arts.

beautiful story …vision…dream and pursuit…Laredo is unique and wonderful…

The interest in the binational identity of the border is growing, and hopefully it impacts the narrow frame through which so many Americans who live in states far away from us fronteristas view us. This heritage and history we share with Mexico should be celebrated, not feared, and the talents of these incredible artists have the ability to share that part of our culture more effectively and with much more grace than our words alone.