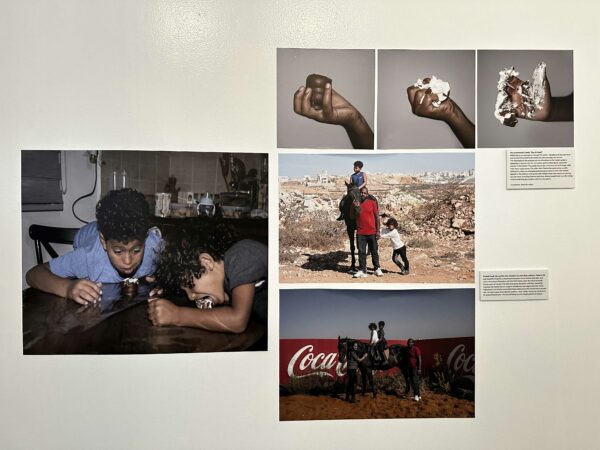

Tanya Habjouqa, “The problematic Candy: “Ras Al Abed”,” 2022, Photo vinyl on wall, dimensions variable. Image courtesy HMAAC.

Negative Women: Four Photographers Questioning Boundaries, an aptly titled exhibition curated by Christopher Blay at the Houston Museum of African American Culture, celebrates the politics of both joy and pessimism, with a discerning eye towards history. There’s clarity in the negative, which exposes the world and its — at times — sinister forces. All four artists — Ciara Elle Bryant, Tanya Habjouqa, Mari Hernandez, and Letitia Huckaby — represent an international and domestic focus on correcting, challenging, and expanding the historical record.

A viewer’s first engagement with the show is the small, cavernous room that houses Ciara Elle Bryant’s roiling multimedia installation Black Shines Like Gold (2022). Reminiscent of Arthur Jafa’s Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016), Bryant’s piece teems with prismic life, drawing upon images that range from the critical, to the calming, to the familial. Bryant deftly collages found material with celebrity images, such as a sunglasses-clad and skeptical Whitney Houston, footage from the civil rights movement, newspaper clippings, advertisements for hair projects, and cartoons. As Christopher Blay put it in a recent conversation about Bryant’s Black Shines Like Gold, the installation “channel-surfs through Black culture, making visual connections through the past 35 years.” Bryant’s use of both outdated and contemporary technology — a video projector and slides — nods to the work’s sweeping, intergenerational reach. As Blay points out, projectors and slides were first used as information tools for entities like schools and businesses; Bryant co-opts these mass-media tools to represent Black culture, unfiltered from its source.

Ciara Elle Bryant, “Black Shines Like Gold,” 2022, (installation view), mixed media installation, digital archival slides, digital archival prints, and video projection. Image courtesy HMAAC.

Alongside this collaged material, the audience literally rides along with an unseen driver as they cruise through a neighborhood, stopping every so often to greet a passerby. On the opposite wall hang everyday objects, such as a wide-toothed comb, a bandana, bamboo earrings, and various close-up photographs of items like jewelry, all in various tones of black and white.

Ciara Elle Bryant, “Black Shines Like Gold,” 2022, (installation view), mixed media installation, digital archival slides, digital archival prints, and video projection. Image courtesy HMAAC.

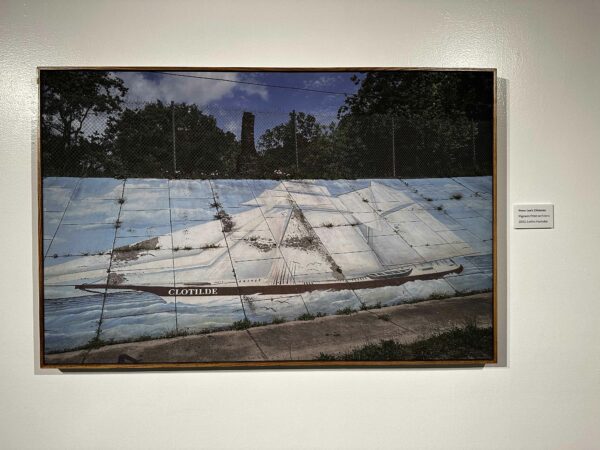

The adjacent gallery space houses a portion of Letitia Huckaby’s photographic series Bitter Waters Sweet, in which she focuses her lens on Africatown, a community outside of Mobile, Alabama. The town was founded by West Africans who were trafficked to the United States after the Atlantic slave trade was made illegal, yet prior to the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. Huckaby’s work responds to the smuggling of Clotilda, the ship that unlawfully brought slave labor, into Mobile Bay.

Clotilda was rediscovered in 2018. The shadow of this dark history literally haunts the cotton-printed frame of Huckaby’s otherwise traditional landscape portraits and close-ups of the earth, such as Black Mulberries (2022), a close-up of the fruit. In Early in the Morning, the sun pierces through a lattice of leaves that loom across the frame. Africatown’s descendants now find themselves amidst a struggle for environmental justice, and made headlines in 2018 when the town sued a nearby industrial plant leaking chemicals linked to cancer. Given the community’s fraught history, both past and present, Huckaby’s work asks the uncomfortable question, “what has changed in the time between Clotilda’s first docking and now?”

In the upstairs gallery, Mari Hernandez’s What Remains points to the malleability of historical narrative through a series of faux colonial-era self-portraits. Whether dressed in delicate white cotton and lace like in Ximena the Voice (2018) or Lucrecia the Light (2018), or militia garb, as in Pitted Brother Against Brother (2018), the purposeful artifice of the costuming locates the viewer in an uneasy and menacing temporality. Mari Hernandez poses as the subject in each of these photographs. In the artist statement written by Hernandez and her collaborator Chad Dawkins, which accompanies the work, the pair write, “For Hernandez, the use of self-portraiture is significant as a means to make herself visible in the work and in the space of the work’s presentation. Referencing art historical precedent, and rooted in early feminist theory, Hernandez makes herself physically present in her work, therefore dictating the subjective content with her own body.”

Mari Hernandez, “What remains,” (Installation view), 2018, inkjet prints on crepe de Chine. Image courtesy HMAAC.

The scale, positioning, and quantity of the works remind one of casta paintings, a series of images used by the Spanish and Portuguese to identify racial mixing and social class. Prosthetics are visible on different parts of Hernandez’s face. There is a quietness to the portraits, which nods to both the cruelty and formality of 19th century colonialism. One of the images ending the series is a photograph of a pale-faced general in a three-pointed hat in a painting titled Cobarde (2019), or “coward.”

Tanya Habjouqa, video still from “Shaden Qous teaches Afro-Debke to young students at the African Community Society in the Old City of Jerusalem,” 2022, multi-channel video. Image courtesy HMAAC.

In a turn towards the archival, Tanya Habjouqa’s Afro-Palestinian, a section of her long-form project The Sacred Space Oddity, represents a collaboration with community elder Mahmoud Jiddah to increase the visibility of Afro-Palestinians in Jerusalem. Bending the anthropological format to her will, Habjouqa uses its tools to harvest a message of equity, justice, and representation. “This chapter focuses on Afro-Palestinian stories of resistance, political incarceration, cultural production, and community,” Habjouqa writes in the work’s companion text. “The exhibition blends imagery, collaborative portraiture, archival material, and ethnographic interviews.” Habjouqa activates the small, room-like space with photographs of the African Quarter in Jerusalem, community portraits, and a video of students learning Afro Dabke, a combination of Palestinian folkdance and Cameroonian African dance. In one particularly effecting series, Habjouqa renders a triptych of the “problematic candy” Ras Al Abed, which translates to “head of a slave,” showing that racial oppression is woven into everyday speech.

Negative Women wields the crisp lens of pessimism to hold history’s feet to the metaphorical fire. While Letitia Huckaby sheds light on uncomfortable parts of North America’s past, Mari Hernandez purposefully molds her own image into that of a number of colonial figures to point to the calculated violence of the 19th century, using prosthetics to highlight photography’s insidious background as an instrument of colonial oppression. Bryant’s all-around gaze on Black culture takes in tragedy along with triumph. Tanya Habjouqa shares her medium with community elder Mahmoud Jiddah to document, celebrate, and reflect upon the untold stories of Afro-Palestinian life. The result is an exhibition that leaves audiences hungry for change.

Negative Women is on view at the Houston Museum of African American Culture through January 21, 2023.