“When I say Blackness is a lack worth having, I am speaking to the dynamic of pain, loss, joy, radicality, and possibility in the experience of being Black. Blackness, if it is anything interesting, has to be determined by and implicated into much more than itself. The true nature of Blackness is multiplicity, not this or that. This aspect of Blackness is not limited to black and belongs to all things we try to name, and will always escape final definition. But the process of coming to terms with no final resolution is a lack worth having.”

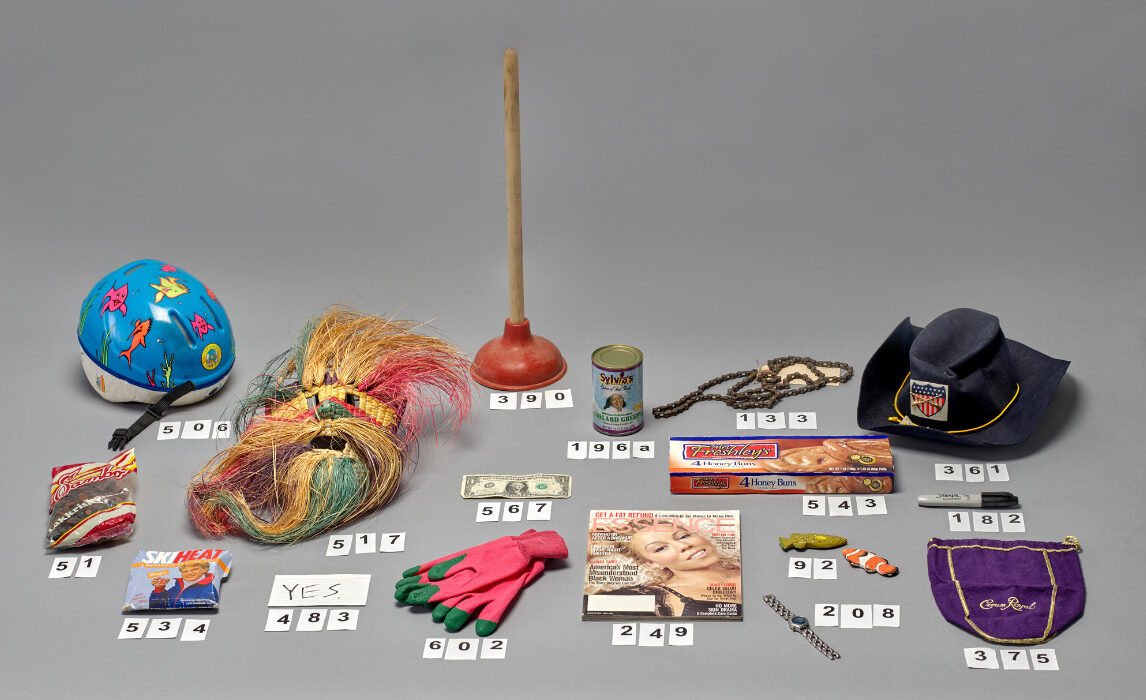

Artist Pope.L died December 23 at the age of 68, at his home in Chicago. Upon hearing the news, I wrote to several close artist friends to reminisce over some of our favorite Pope.L artworks. He had been a constant influence, and we mourned the loss of a critical mind and unique voice. I met Pope.L in Baltimore, when I was a finalist in an exhibition he had juried. Having a conversation with him about the artwork I was making in the streets of Washington, D.C., after the September 11 attacks and during the era of the USA PATRIOT Act, was an insightful and affirming experience. Later, when The Black Factory came to the Washington, D.C. area, I went with a group of friends to submit objects to the archive.

His art addressed race, class, and masculinity in ways that subverted expectations of how an artist could approach difficult issues. Using humor and absurdity as tools, Pope.L destabilized deeply entrenched cultural assumptions and left the viewer to fend for themselves. For me personally, his appeal was not only the work he produced, but what I learned when he spoke about it.

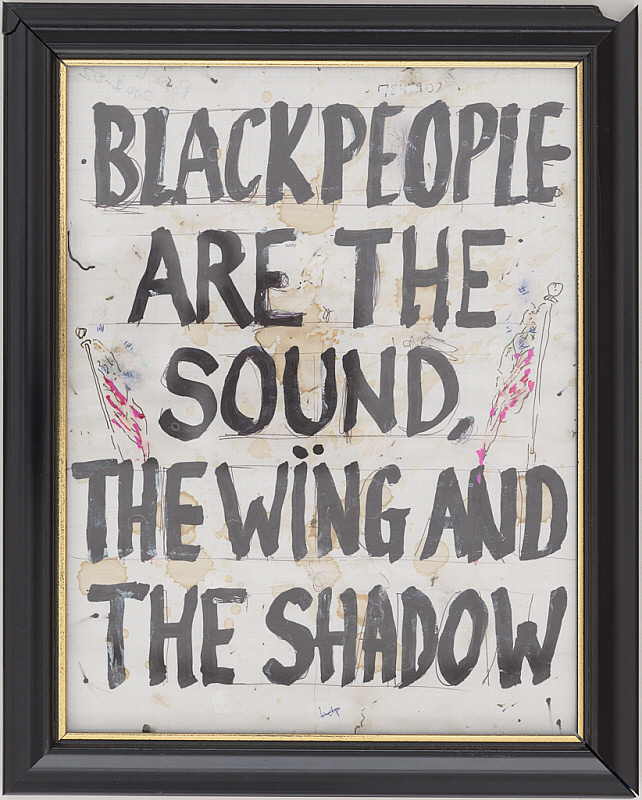

Pope.L, “Black Drawing: Black People Are the Sound, the Wing and the Shadow,” 2000-2002, pen and marker on graph paper, 12 ¾ × 10 1/8 × 5/8 inches. The Menil Collection, purchased with funds provided by Clare Casademont and Michael Metz in honor of the inauguration of the Menil Drawing Institute

2019-3.3

Over the course of his 45-year career, Pope.L produced an extensive body of paintings, drawings, videos, and most importantly, performances. His early performance work from the 1970s, often staged on the sidewalks of New York City, spanned the changes to urban space the city saw under Mayors Koch, Giuliani, and Bloomberg. Quality of life campaigns and stop-and-frisk programs introduced by the city proved to have disparate impact on its citizens. As the city transformed, so did acceptable behavior in public space.

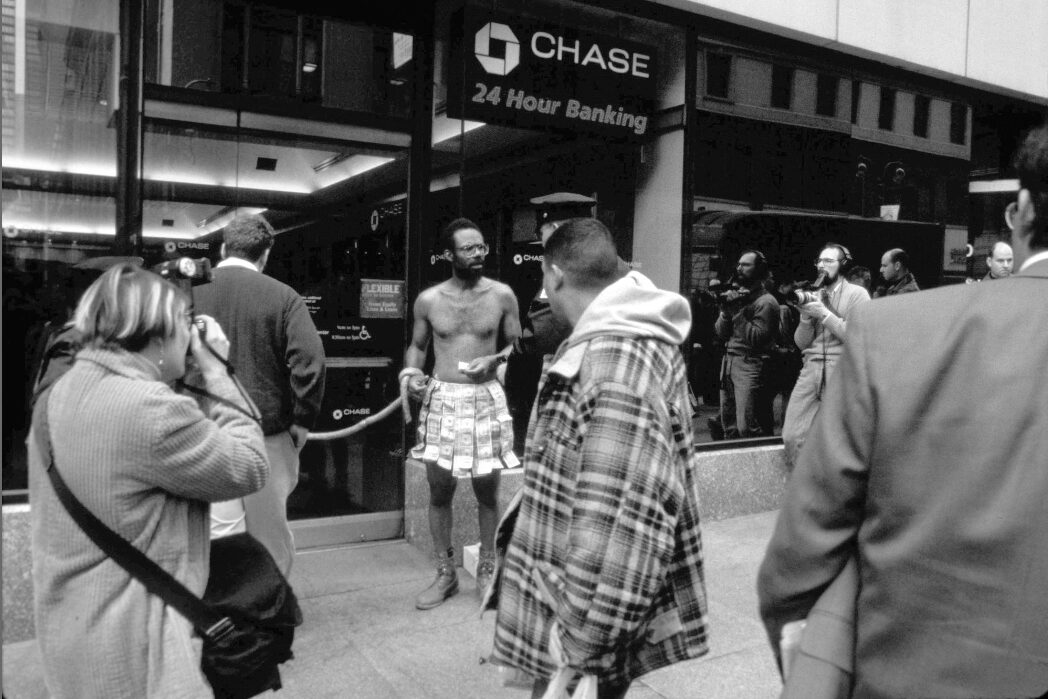

When Rudy Giuliani banned panhandling near automatic teller machines, Pope.L, in “an attempt to bring fresh discomfort to an age-old problem,” produced ATM Piece, a performance in which he wore a skirt made of dollar bills and tethered himself to the doors of a bank with a chain of sausage links. Instead of asking for handouts from passersby, he distributed money. The piece was shut down by police within minutes. Like many of his early performances, ATM Piece confronted unknowing audiences in public spaces without the protective barrier of the gallery. In doing so, Pope.L rendered visible disenfranchisement at the risk of his own safety.

One of his first and most important performances, Times Square Crawl, was produced in 1978. In the piece, Pope.L, wearing a dark suit with a yellow square sewn on the back of his jacket, moved along 42nd street in a low crawl. He inched past adult theaters, over crosswalks as traffic waited, and along trash-strewn sidewalks.

“To perform, you have to find power in being someone else. You always want to be clear about the separation between yourself and what you’re characterizing, but because these things took a while, I was usually crawling for long periods of time, I would forget. So the suit, in a way, allowed me to protect myself from the act of doing it.”

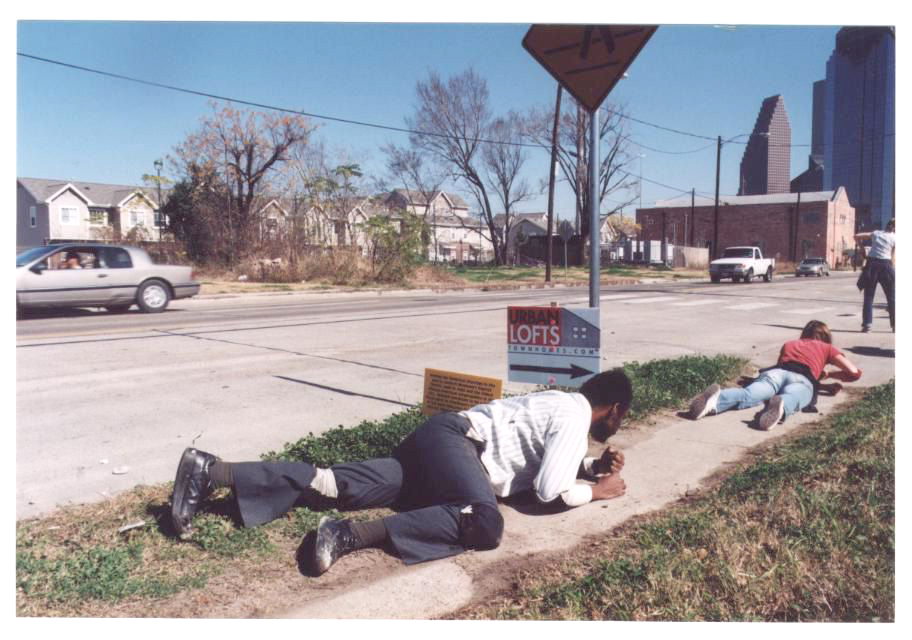

He would go on to perform several crawls, including the 22-mile Great White Way, performed over the course of nine years, during which he wore a Superman costume with a skateboard on his back in lieu of a cape. In 2003, he crawled through Houston’s fourth ward in Freedman’s Crawl as part of his DiverseWorks exhibition, eRacism. The show traveled widely and yielded the catalog The Friendliest Black Artist in America.

He commented years later: “The street situation put me in a circumstance where I had to adjust to whatever was there. No matter where I did crawls of that nature, I had people yelling at me and spitting on me.”

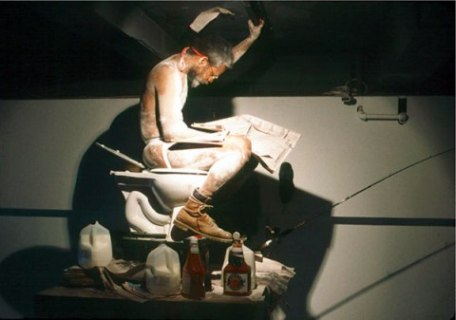

Pope.L’s art was shown in Texas several other times in the last 20 years. A decade after the DiverseWorks exhibition, he returned to Houston in Valerie Cassel Oliver’s Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, where he installed the props used in another seminal performance: Eating the Wall Street Journal.

Installation view of Pope.L’s “Eating the Wall Street Journal” in “Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art” at the Walker Art Center

The piece was first performed in 2000 and is exactly what it sounds like: Pope.L tore strips from the newspaper and chewed them, using milk and ketchup to help mask the taste of printed journalism. Covered in flour and wearing only a jockstrap and Timberland boots, he perched on a toilet that itself sat atop a shoddy, wooden tower, as he slowly chewed and spat out the wads of newsprint. Said the artist of the Wall Street Journal: “It’s not very tasty.”

As with the crawl performances, Pope.L restaged this piece several times. Shortly before his death he told The Art Newspaper: “Versioning is a way of creating incompleteness and ongoingness at the same time. The idea of a finished artwork is a fiction. The claim of ‘being done’ is wishful thinking and a bit impatient.”

In recent years, Pope.L’s work has received well-deserved accolades. A retrospective in 2019, organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Public Art Fund, spoke to the importance of his contribution to contemporary art. In 2017, he won the Bucksbaum award, a $100,000 prize which recognizes a Whitney Biennial artist whose work is urgent and inventive. That same year, he was featured in Documenta 14 in Athens, Greece.

Pope.L made art that was as fearless as it was funny. He produced a body of work that was marked by unrelenting inventiveness and a commitment to the issues he returned to over the course of his 45-year career. His presence on the street, at the lectern, and in the white cube was radical. It is his absence that we must reconcile.