At first, when seeking an angle for this Halloween-themed Ten Texas Artworks piece, I was at a loss: Glasstire recently released a list of the most twisted artists in Texas; covering “spooky” art was too general; Christina Rees had already written about the unsettling awesomeness of Christie Blizard’s Instagram; and Neil Fauerso had just covered which horror movie scenes are practically art.

So my attention turned to skulls.

And for me, the subject of skulls quickly expanded to the use of and depictions of bones in art — the whole skeleton! — and the brainstorming began. Bones are fascinating to a lot of people, but often unconsciously — we often don’t think much about bones until they’re broken, and they’re somewhat imbued with taboo mystery. This is because we generally don’t get a chance to see our own, and those we do see have come from someone or something deceased. And when viewed through an obscured lens, an X-ray, bones help us understand that on the inside we’re all the same. The fascination with the very personal and unseen extends to artists’ use of bones, skulls, and skeletons — real and depicted — in their works.

Sharon Kopriva’s works in the Sculpture Month Houston exhibition From Space to Field in 2016

It was hard to choose which artwork best represents Houston artist Sharon Kopriva’s use of bones. Many of her macabre works (they’re all macabre, though some more than others) address the decay of our corporeal selves. Her installation in 2016 in the Houston rice silos at Sawyer Yard framed this work really well — the disused industrial backdrop brought out her work’s spook factor.

This still from Delilah Montoya’s video installation about Doña Sebastiana (aka Santa Muerte) reminds us that bones can be beautiful.

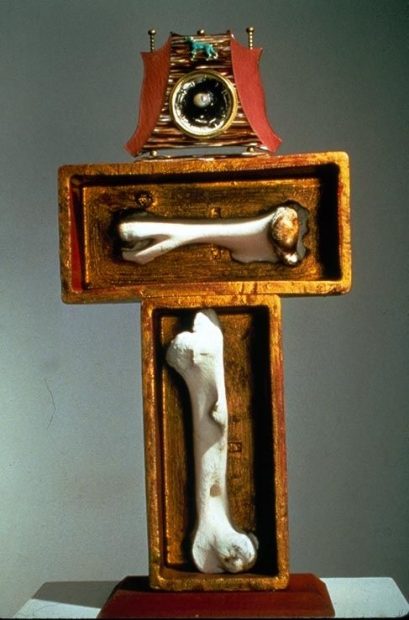

Bert Long, Shrine of the Black Madonna of Guadalupe, 1991, Acrylic on plastic with bones from Spain, glass eye, clock from Rome from Janet and Peter Shaudt mounted on tree stump.

Bert Long’s relic boxes echo the feel of religious shrines, minus the pomp. We know that if a human bone is not in a body, then it’s likely their original owner has left this world. Adding to the mystique here is that although we don’t know who this bone belonged to, we know it made its way to Texas by way of Spain.

Though less overt, Trenton Doyle Hancock’s imagined characters have bio-skeletal systems (or sometimes a lack thereof). At times, his use of bones illustrates a character’s character, and his exploration of a biological process lifts a curtain on the grotesque.

A master of materials, Fort Worth-based artist Helen Altman casts skulls out of various spices and seeds in an attempt to see if the object’s ineffable magnetism is in full effect when only its form is present.

West Texas artist Boyd Elder recently passed away. Elder was known for his painted skulls; for him they are both relics of ranching in the region, and powerful symbols of the afterlife and an accompanying Southwestern mysticism. They also graced several chart-topping Eagles album covers.

In a current show at Sala Diaz in San Antonio, San Antonio-based artist Jimmy James Canales subtly jabs at the folly of technology, which is represented by a PVC exoskeleton with attached GoPro camera. Donned by the viewer, the wearable structure’s counterweight, a bucket, crushes a skeleton on the floor — a comment on how our very core is burdened by our advances.

San Antonio artist Lisette Chavez uses a skull to represent what skulls are usually taken to symbolize — Death with a capital D — in a baby mobile from hell.

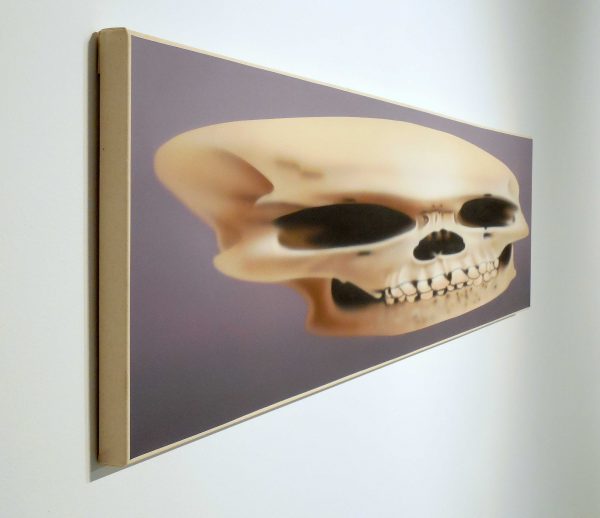

A painting by Houston artist Rachel Hecker. Installation shot from the artist’s 2013 exhibition at Art League Houston

In a nod to Hans Holbein the Younger, Rachel Hecker’s enigmatic painting points out that skulls (in art and in life) are nothing new. The piece should be viewed from different angles to get the fully warped and contorted effect — see that here.

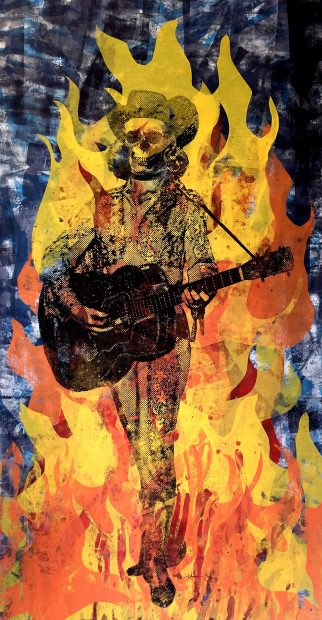

What art-bone list would be complete without Houston artist Carlos Hernandez? From commissioned gig posters to his own art work, Hernandez’s bones and skulls abound, granting his characters a sort of timelessness. They can’t die if they’re already dead.

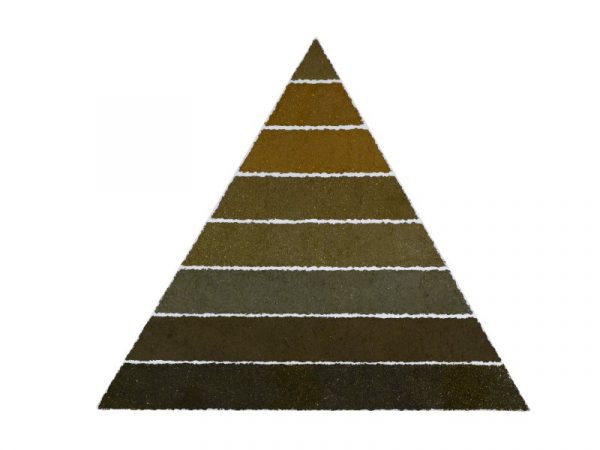

Okay, I lied. This list is eleven artworks long because I couldn’t not include Houston artist Wayne Gilbert. Twenty years ago, Gilbert began using human remains to create his paintings. His work honors the lives of the people within them while noting our communal fate — people of every social class, religion, and race die and physically end up in the same place. Gilbert’s work also highlights some differences; each person’s cremation results in a unique color of remains. Symbolically then, each person Gilbert uses in his art has their own unique story that is completed when he incorporates them into a painting. Though his pieces aren’t just bones, they are made of people — bones and all.

Happy Halloween.