I’ve been curious to see the inside of the Success Rice grain silo building in Houston for years. It has long been the mythical, empty space looming on the horizon, sitting with unfulfilled potential. Over the past year, the Washington Avenue Arts District has been breathing life back into the space through a series of curated shows in which artists are assigned a silo to invade with their work. SITE Houston, on view from November 2015 to January 2016, was the first exhibition in this series. The second show, From Space to Field, part of Sculpture Month Houston, is currently on view. While both shows have had their standouts and low points, here are two things I’ve noted from seeing two exhibitions in this unusual space.

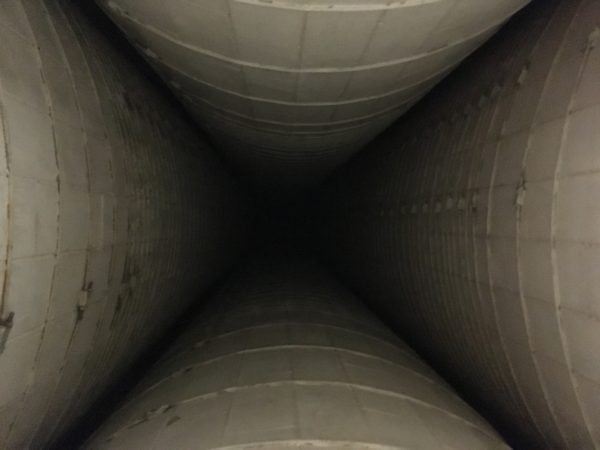

1. The building threatens to dominate anything that is shown within it. On the opening night of SITE, the first show from last winter, instead of focusing on the installations created by artists, visitors were often looking at the drastic up lighting that highlighted the architectural features of the silos. Art can only compete so much with the space it occupies, which is why galleries are clean white cubes without distraction and ornamentation. For SITE Houston, each artist had their own silo, and thus their own shot at capturing an audience. But the show was punctuated by the dramatic transition areas of the building where everyone looked up and marveled at the telescoping walls. The art had trouble competing with that.

Most of the silos were still raw for the first show. Markings and traces of the building’s past life as an operating grain silo were visible; functional graffiti covered the walls of the circular galleries. This too was distracting—there is a enigmatic quality to the painted red letter-number combos marking each space. This was too much static for some of the artists; a number of the silos had been whitewashed (save for Plexi plaques covering the number and letters). The artists who chose to do the whitewashing essentially turned the silos into a gallery space. They made it their own by an all too easy means—which brings me to my next point.

2. People, even artists, can confuse site-specific art, installation art, and simply putting a sculpture in a space. The Tate’s website defines site-specific art as “a work of art designed specifically for a particular location and that has an interrelationship with the location.” Compare that to its definition for installation art: “mixed-media constructions or assemblages usually designed for a specific place and for a temporary period of time.” For me, the big distinction between the two has to do with one key word: interrelationship. It is a rare breed of artist who can tease out a real relationship between their art and the space it’s in that doesn’t seem forced or trite. One of the most successful pieces in From Space to Field is the site-specific installation Success by Chris Sauter. Here, Sauter creates a piece of art that not only works with and for the space, but also fits naturally into his own practice. Inside the base of the silo sits a satellite-like object that is gradually being filled with rice that periodically falls out from the silo spout above.

And The Fleeting Moment of Success Space by Jeff Forster is strong enough to compete with (and compliment) the the building itself. Forster’s silo is punctuated top to bottom with detritus from a space mission gone wrong. The Success Rice logo is brandished on torn parts of the crashed craft, all of which are meticulously sculpted from clay. Sauter and Forster’s site-specific pieces are so successful because they don’t just occupy a specific space—they interrelate with the building itself. They respond to the actual architecture. Sauter revitalizes the silo so that it regains its original function of dispensing grain; he uses the distractions of the building to make his piece work. Forster capitalizes on our desire to look up into the building by making his spacecraft crash land so that it gradually loses parts along the way—he uses the full height of the space so that wherever we look, we see his work.

Some of the most underwhelming works in From Space to Field are sculptures plopped in the space that have no reason to be there other than the fact that they are sculptures. Michael Kennaugh had a small silo housing three sculptures sitting on pedestals. I have an affinity Kennaugh’s objects, but this time in this context, they don’t hold their own. Kyle Olson’s Tug of war cannot be won is unconvincing in its construction and also makes no connection to the silo space.

Many artists created truly nice installations in the building—the kind of art I’d call not so much site-specific as just good installation art. The graffiti laden walls of the silos were a perfect backdrop for Sharon Kopriva’s hanging corpses. The creepy, abandoned feel of the building adds a sinister element that the work would lack in a cleaner space. Adela Andea has created a light installation within one of the circular galleries and it completely commands the space by dousing it in a cool purple glow. And Jo Ann Fleischhauer’s interactive The Library of Babble is a unique, one-at-a-time viewing experience that slowly reveals itself the more time you spend with it.

As we see more shows come and go from the silos, I hope the Washington Avenue Arts District will figure out how to best use and curate the space. For example, it would be smart to play to its strengths and bring in sound artists who could really play with the acoustics of the building (Eric Thayer did this in SITE Houston). It would also be nice to invite an artist who really knows how to create site-specific installations to execute multiple works across the silos as a sort of solo show. Everyone would go see it. If not for the art, then at least for the building.

1 comment

I am afraid that you missed one of the most successful installations in the From Space to Field Exhibit, it was the sculpture by Dylan Conner. His concrete sculpture was a perfect marriage of sculptural form and the existing structure, industrial function, and proportional dimensions of the silo space.