Para leer este artículo en español, por favor vaya aquí. To read this article in Spanish, please go here.

Lisette Chavez uncovering one of her drawings in the installation Cafeteria Catholic, 2017, Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, San Antonio. This installation was inspired by a real act of concealment: in 2010, her mother covered Chavez’s lithographs of skulls and devil heads with towels because the imagery frightened her. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova.

“I lied at my first confession,” confesses Lisette Chavez, a San Antonio-based graphic and installation artist. She was mortified by the gravity of participating in this critical ritual. Confession is a sacrament in its own right, as well as the necessary prelude to the supreme sacrament of communion, wherein the young girl would— for the first time — eat the transubstantiated body and blood of Jesus Christ. Chavez had delayed her confession until the last possible moment before her long-awaited first communion, and she had to be literally shoved into the confessional booth by her devout and by-now-very impatient mother.

“I still feel guilty about it,” Chavez adds. I wondered why Chavez had altered her sins. Did a tiny devil inside of her tempt her to violate the sanctity of the ritual and perjure herself before God’s Representative on Earth? Did the little demon make her test whether God and His Minions were indeed as All-Knowing as they were made out to be?

Lisette Chavez, framed text, from Three Hail Marys, Two Our Fathers, 2016, Provenance Gallery, San Antonio. Photo source: Alma Hernandez.

The explanation she gave me was very different from what I had imagined:

“I was too embarrassed to tell the priest my actual sins so I thought of some ‘lite’ sins. I hadn’t been able to sleep the weeks prior to this deadline because I kept wondering which sin was worse, which one would give me a greater punishment. I mostly thought of how much the priest would be ashamed of me. Instead I opted for a more ‘peewee’ sin. I think I said that I didn’t clean my room, I talked back to my mother and there was another that I can’t remember. I was also too young to know this but I was having a panic attack during my confession. I somehow remembered the prayer I needed to say to the priest but I couldn’t stop the sound of my heartbeat pounding. I suffer from panic attacks and this was my very first one; it starts with my heartbeat pounding in my ears. Then I have a choking feeling around my neck and I literally can’t speak. I was terrified and glad when this confession was over.”

In any case, her confessor meted out a fairly standard punishment of three Hail Marys and two Our Fathers — no doubt a lighter sentence than Chavez deserved — which she dutifully recited in order to atone for her whitewashed sins. But, under these circumstances, did she merit the sacrament of communion or the Wrath of God? This traumatic experience inspired Chavez’s most important and revealing installation to date, titled Three Hail Marys, Two Our Fathers, which will be discussed in more detail below.

Lisette Chavez with the installation Three Hail Marys, Two Our Fathers, 2016, Provenance Gallery, San Antonio. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova.

To this day, Lisette Chavez is perched upon the razor’s edge of incredulity and wonder, suspended between the chasms of belief and disbelief. She is not willing to take the skeptical leap that could potentially plunge her down into the Eternal Fiery Abyss of Hell, nor does she possess the indubitable faith that should gain her the Kingdom of Heaven (assuming everything her mother told her is true).

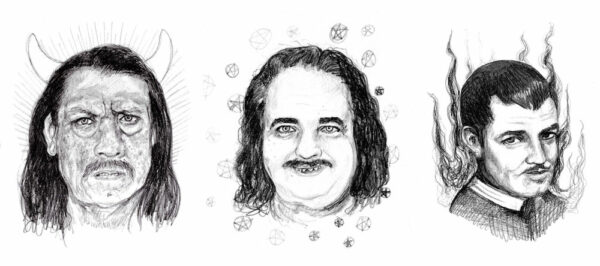

Lisette Chavez, images from the zine Men Who Look Like Satan, 2016. Photo source: courtesy of the artist.

The threads of belief and disbelief are thoroughly interwoven into the fabric of Lisette Chavez’s art. They are the warp and weft that give it substance and form. On theological details, as well as family oral histories, she gravitates between thinking “How can this be true?” and “How can this not be true?” without any kind of resolution. In place of religious certainty, she utilizes the forms of the faith she has inherited to look for beauty in “those things we fear,” and to address “that which we cannot explain.”

With considerable frequency, in every conceivable social context, Chavez’s mother would make a rapid sign of the cross, utter a short prayer, and declare to Lisette: “That man looks like Satan.” The artist has transmuted these experiences into a much-coveted zine (I have my copy!), from which three film stars from very different walks of life are illustrated above (Danny Trejo, Ron Jeremy, and Clark Gable). Given the current supply of Satanic-looking men, a second volume is in production. If you are standing at the checkout counter and Chavez makes a rapid pencil sketch of you, now you know why.

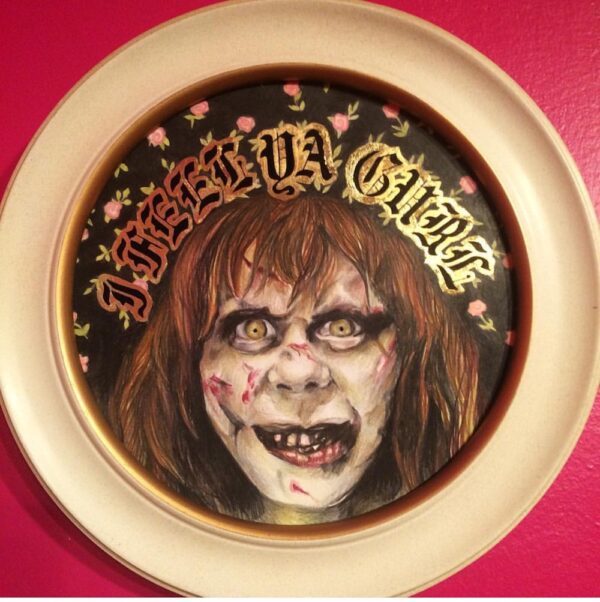

Lisette Chavez, roundel with image of possessed girl from Three Hail Marys, Two Our Fathers, 2016, Provenance Gallery. Photo source: courtesy of the artist.

Chavez identified deeply with Regan, the possessed girl in William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973) played by Linda Blair. Unlike Regan, Chavez cannot turn her own head 360 degrees. But she can nod in sympathy and say, “I Feel Ya, Gurl” in gold-encrusted Gothic script.

Chavez did not look and act the way her family wanted and expected her to look and act. She felt they behaved as though she were possessed. Chavez recounts a particularly terrifying intervention that almost mimicked an exorcism:

“I identified with her because as a teenager my mom was often embarrassed of the way I dressed (Gothy) and she didn’t understand my teenage mood swings and attitude. At one point she called my uncle (who was a preacher) and my aunt over to ‘pray over me.’ They all sat me at the dining table and held their hands over my head, I felt like something was really wrong with me, it was an embarrassing experience and afterwards they told me that I would ‘feel better’ and ‘needed to pray.’ I felt like a freak and was often treated as if I was possessed. I sometimes watch that movie for breakfast and still see the shame in Regan’s mother’s eyes and recognize that I saw the same stare in my own family.”

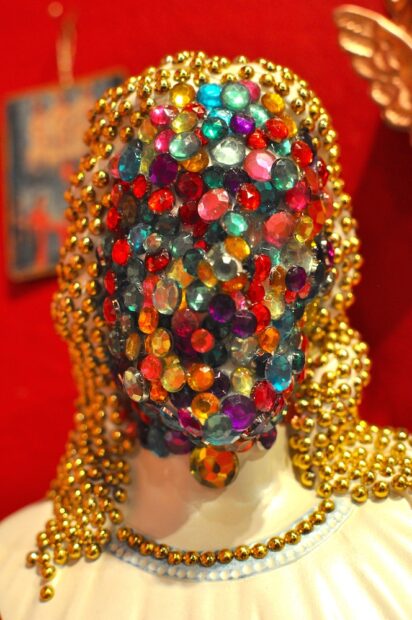

Lisette Chavez, detail of rhinestone-encrusted Jesus, Three Hail Marys, Two Our Fathers, 2016, Provenance Gallery. Photo source: courtesy of the artist.

If this rhinestone-encrusted Jesus could only speak, perhaps, in his heart of plastic hearts, he would say: “Dale SHINE!” (Go here for Santiago Garcia’s explanation of this idiomatic expression.)

I have wanted to write about Lisette Chavez for a long time, and with the opening of her pandemic-delayed exhibition From the Horse’s Mouth at Palo Alto College in San Antonio, I am taking that opportunity.

Born and raised in the Rio Grande Valley by deeply religious parents, death was a most familiar companion to young Lisette, who had a traumatic face-to-face encounter with it at the age of four. At her grandmother’s funeral, her mother lifted her up and forced her to take a long, close look at the corpse. Suspended over the casket, the “rosary, wrinkles, bruises, [and] a lot of the ruffles on the inside of the coffin and the crucifix” were all deeply imprinted onto the future artist’s young mind (Bryan Rindfuss, “Studio Visits: San Antonio Artist Lisette Chavez on Growing Up Catholic, Devil Babies and Men Who Look Like Satan” San Antonio Current, July 3, 2019).

The experience of seeing her grandmother’s corpse also planted troubling seeds of doubt and confusion in young Chavez’s mind. Her first response was confusion and disbelief:

“I was a bit too young to know about Hell but I think I had a very small understanding of Heaven. I was very confused about the woman who I was told was my grandmother. It didn’t look like her and I didn’t quite understand why my mother was making such a big deal about this. She just would not let it go. I tried standing on the kneeler but was too short, so that’s when my mom picked me up and held me over her body. I remember feeling uncomfortable and scared, I think I was trying to push myself away from her dead body.

“My mom was in deep grief after losing her last parent, her mother. I think she didn’t want me to miss the opportunity to say ‘goodbye’ but I just didn’t think this body belonged to my grandmother. I’m not sure I even understood what a dead person was at the time.

“A few years ago I learned that therapists do not recommend taking a child to a funeral if they are under the age of 10, because their minds cannot comprehend death. It can be traumatizing for those reasons. As an older person I understand that my mother was just trying to help me seize the opportunity to look at my grandmother for the last time. As you know, the body — especially of a dead family member — is very important to Catholics. This is one reason why I struggle with the idea of being cremated. I just hate it. When my parents talk about family members or other people being cremated they usually describe it as ‘they burned her/him.’ Which sounds absolutely awful.”

In later years, Chavez didn’t know how to process something her mother had told her at the funeral: “You’ll never see each other again.” Young Chavez wondered: “Did this mean that Heaven was a lie?” Could it mean there was no Heavenly Father watching out for her family? Did mom know or suspect that her own mother and her own daughter were not both destined for Paradise? The possibilities were almost too horrible to contemplate. Deep down inside, she feared she knew the answer to the question she dared not ask.

Rindfuss terms Chavez’s mother a “funeral fanatic.” Death — and the rituals and observances associated with it — were at the heart of her devotions. Rindfuss recounts Chavez’s memories of mourning:

“I can’t even tell you how many funerals I’d been to by the time I was 10,” she said. “[My dad and I] would make fun of my mom … He’d be like, ‘Oh, your mother’s a professional mourner.’ She’ll open the newspaper and go straight to the obituaries in the morning [and] be like, ‘So-and-so died, and I knew his cousin. I’m gonna go to that funeral.’ And they’re really intense, you know? Especially the ones in Latino families. Lots of praying, lots of crying. Very dramatic. And she just loves it… I told her, ‘Mom, you’re so Goth.’ I would tell her that when I was in high school… But now I see [that she’s] trying to be there for someone during their darkest moments… And so now I see it as a really sweet thing.”

At the same time, we can understand this mortuary obsession as something that helped Chavez’s mother cope with her own mortality — and that of her family members, including her mother, with whom she had an extremely conflicted relationship. The youngest of 13 children, her parents were old when Chavez’s mother was born. Chavez observes: “She basically saw her entire family die. None of her immediate family is alive anymore, she has no siblings now, no parents.”

Chavez also relates a story she heard that could have bearing on her mother’s fascination with death:

“When my mom was a little girl, she and her brother were playing hide and seek at a funeral home and they accidentally opened the door to an embalming room. She said she saw the body of a naked woman and a man hanging upside down. They were draining the bodies. I don’t even know how true this is. But if it is true, then she was probably definitely traumatized at a young age. And it’s probably the reason why she’s so morbid and obsessed with death.”

Catholicism is centered on a grand cosmic struggle between God and the Devil, but it is not a battle that is fought in the vast reaches of space, nor on the home grounds of Heaven or Hell. It is waged on the battleground of individual bodies, one soul at a time. In modern Catholicism, ones’ spiritual standing at the precise moment of death is all-important. There is no ancient Egyptian-like final judgment in which an entire life is weighed in the balance. Instead — regardless of how exemplary a life you have led — if you die with a mortal sin that has not been expiated (by a sincere act of contrition directly to God, or by any confession — however flawed — in which a priest offers absolution), you are going to Hell. Mortal sins are myriad. They include murder, abortion, sex outside of church-sanctioned marriage, and missing church on Sunday without a compelling reason. Unsurprisingly, such penalties are great sources of anxiety.

Freud described the “compulsion to repeat” as a mode of dealing with trauma and loss, most extensively in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920). It was his explanation for why people continuously relive or recreate distressing situations from the past (often family relationships).

When Chavez lived in the Valley many years ago, a psychiatrist who saw her work at an art fair purchased several pieces. She astonished the artist by inquiring: “What happened to you?” Chavez, who didn’t understand why her work was so focused on death, asked her what she meant. The psychiatrist responded, “Something must’ve happened to you if your work is so much about death. I love it!” Chavez told the shrink about her experience at her grandmother’s funeral. She replied: “Ahh, that’s what it is! You’re trying to recreate that feeling that came over you when you saw her body.” Chavez never saw the psychiatrist again, but subsequently learned that she had been in a car accident as a little girl — one that killed all of her sisters. “No wonder she collects work about death,” concludes Chavez.

Obsessive re-enactment can serve as a mechanism to re-master or cope with past trauma, as well as to cope with, or prepare for future trauma that might be anticipated, or even unconsciously feared. More broadly, we can see that repetition can be calming and reassuring in an ordinary religious context, such as praying the rosary while fingering its beads, which many people do when they are anxious or stressed. It enables the body and mind to say, in effect,“We have been through something like this before, and through prayer, we have survived it.” In church, Chavez still finds it calming and reassuring to hear a chorus of prayer during the mass. These mass prayers served to calm Chavez in the past, and she thinks they will serve to calm her again in the future. Prayers are akin to deposits in a spiritual bank account; they accumulate for future use. Prayers are spiritual currency, they are counted, they are “bankable.”

It can be hard to break from established patterns of behavior, simply because they are familiar. On the subjects of maternal role models, repetition, and patterns of behavior, Chavez told Rindfuss:

“My mother — it always goes back to my mother,” she said. “The relationship with my mother is really toxic but it’s also addicting. I just can’t get away from it, it’s horrible. There’s some kind of crazy dynamic there. I see myself doing a lot of the same things she does.”

Chavez amends and clarifies this statement: “I think it was mostly toxic when I was younger but we get along very well now, more so than ever. We laugh a lot and she has a really great sense of humor.” Chavez adds that her mother’s life-long morbidity proved helpful when Chavez was widowed last year. Her mother “was there with me every step of the way.” She assisted her with “some really difficult parts of burying my young husband.” Chavez says her mother would do anything for her. Additionally, she still tells her to pray and that she needs to believe in God. “Sometimes I do and sometimes I don’t,” notes Chavez.

Chavez wanted to be an exemplary daughter, but she didn’t know how to accomplish that goal. At the age of 17, she declared that she wanted to become a nun. But her announcement did not elicit the response that she had hoped for. As Chavez told Rindfuss:

“I was an outcast in high school too. I thought my mother would be happy when I told her I wanted to become a nun, but she was very angry. [She] told me I was crazy, and she [forbade] it. The mixed signals from my home life were very confusing.”

Chavez’s art is marinated in the tears and trauma of her Catholic upbringing. It is filled with extremes of love and fear, and also with heady doses of defiant ambivalence, sometimes with subject matter that seems schizophrenic. She is attracted to the visual forms of the Catholic faith, especially to the popular devotional objects that everyone can possess, and to its demonstrative, public pageantry. Chavez also characterizes her art as a confession of sorts, one that reveals her unresolved religious ambivalence.

Lisette Chavez, The Transient, 2003, mixed media on paper, private collection. Photo source: courtesy of the artist.

Chavez always loved to draw. She moved to San Antonio, where she received a B.A. in art from the University of the Incarnate Word in 2003. The Transient is a self-portrait made during Chavez’s senior year whose title references her sense of mortality. She recalls that period as a time of searching, of “really trying to find myself, I felt lost. I was also thinking about death a lot, I always was.” She imagined its setting as “some sort of barren place” that reflected her anomie. “I often felt very numb and unable to connect with other people.”

Miguel Cortinas was Chavez’s professor for drawing. He made experimental, mixed-media works, the likes of which she had never seen before. His example inspired Chavez to utilize different materials, and to refrain from treating the surface of her drawings as “precious,” inviolable substances.

Cortinas also introduced Chavez to spray paint. She sprayed black paint through stencils that she had made to represent stylized bones. The multiple layers of stencil work suggest the semi-opaque layering familiar from x-rays. When Chavez didn’t like the eyes that she had rendered in pencil, she cut them out with an x-acto knife.

A psychoanalyst could have a field day with this self-portrait, since Chavez literally blinds herself. She then made a drawing of bandages that resembled a blindfold on a second sheet of paper, which she glued to the back of the self-portrait. This created unsettling spatial effects because the blindfold, which should be over her face, is actually under it. At the same time, it appears to be over the bangs that extend under her eyes, yet beneath the hair on the sides of her head. The black outline that Chavez made around the blindfold contributes intimations of rupture and instability. The touches of red paint imply suffering and vulnerability.

Chavez has put out her own eyes, bared her bones, and de-centered herself spatially on the sheet of paper. Unable to “see,” how can this transient navigate the world? Or, contrarily, she might be undertaking an internal, or spiritual journey.

The work is haunting, suggestive, and unsettling. Speaking of this drawing in the context of her entire body of work, Chavez explains: “In a way, I do feel as if I’m still making self-portraits; everything I make is so autobiographical.”

As a curator, I included The Transient in the exhibition Arte Contemporaneo at the Centro Aztlán in 2004. It mixed some very well-known Latinx artists with emerging artists. Chavez is one of the artists mentioned in a short notice in the Express-News about the show, which might be the first press she received. She has since exhibited nationally and internationally, and her work is in many museum collections.

Chavez returned to the Valley in 2004, where no suitable jobs came her way. Due in part to her memorable encounter with her grandmother’s corpse and to her mother’s fixation on death, Chavez explored the possibility of mortuary science as a career. When she saw the casket room, Chavez became excited. She likened it to seeing “a car show.” She observed an embalming as a trial experience. Chavez thought it was beautiful, but she cried after the man who performed it likened it to “taking out the trash.” His comment appalled Chavez. She, in fact, regards the mortician’s comment as a work of “fate” that served to redirect her away from a mortuary career path back to an artistic vocation. Chavez discusses this experience — and many other things, including coping with the recent death of her husband — in episode 73 of Hello, Print Friend (December, 2020). In this podcast, Chavez also talks about a trip to Oaxaca during Day of the Dead in 2009. It was a positive experience that helped to provide a framework for her Early Mourning installation.

Lisette Chavez, Early Mourning (view of interior), 2011, installation at Texas A&M University—Corpus Christi. Photo source: courtesy of the artist.

Chavez enrolled at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, where she discovered lithography and received an M.A. in studio art in 2011. She had her first experience with installation art at A&M. Early Mourning, her senior thesis, featured art inside and outside of a mini-chapel that memorialized her grandmother. Chavez likens the exterior to a dollhouse/mausoleum, whose “windows” were suggested by framed lithographs. Two hundred clay cicadas — symbolizing rebirth or resurrection — were affixed to the facade. The artist’s personal collection of death-related objects decorated the interior.

After A&M, Chavez went to the University of Arizona at Tucson, where she received an M.F.A. in 2014 with an emphasis on printmaking. At Tucson, a studio visit in 2011 with Barbara Penn, a painting professor, had a transformational effect on Chavez’s work.

Penn asked her students to present their recent work and to also bring books and illustrations by artists they admired to the session. On one table, Chavez placed her lithographs, drawings and photographs of her Early Mourning installation. Another table held images by artists Chavez liked: they were artists with edge, who made dark and macabre art, including Laurie Lipton, Joe Coleman, and Aurel Schmidt. After inspecting the two tables, Penn asked Chavez why her work was so “sweet and innocent,” while the work she admired was “so wild.” Chavez responded: “It’s probably because I was raised Catholic.” Penn told Chavez that she had “hit the nail on the head,” and to keep “thinking about that.”

It took a long time for Chavez to understand the significance of this experience: “That studio visit changed my life but I didn’t know it at the time.” Gradually, she came to understand that she had always viewed the word through the Manichean lens of Catholicism — and Christianity in general — wherein everything is all-good or all-bad: “I realized how black-and-white I saw the world, and how I viewed my own personality and my actions.” Chavez likewise came to understand the negative effects of such a worldview: “There was no in-between and it’s suffocating and it creates a lot of pressure on a child throughout their upbringing.” The consequences of this upbringing are still with her: “Even as a grown woman I still struggle with the guilt from doing something that is considered ‘bad.’”

The summer before her thesis year, Chavez had still not found a final project when she prepared to leave for a one-month residency she had received at the Vermont Studio Center. A painting professor advised her: “Have fun, nobody knows who you are or what kind of work you do, be someone else.” So she “tried to let loose” by drawing new subjects, including conjoined kittens she had found online. One thing led to another:

“I asked myself what other thing would be fun to draw so I started drawing penises. So as I’m drawing these penises I’m giggling and all of a sudden someone knocked on my studio door and I just about threw all the drawings off the table. It was at that moment that I realized I had been censoring myself and hiding most of my life. This was all due to the pressure of being raised in a conservative Catholic family. My parents made it very clear that I needed to be a ‘good girl’ and present myself in a conservative manner.”

Lisette Chavez, detail of penises from Three Hail Marys, Two Our Fathers, 2016, Provenance Gallery. Photo source: courtesy of the artist.

Previously, because Chavez didn’t want her family to see the kind of things she really wanted to make, she simply had not made them.

Upon her return to Tucson, Chavez began confessing: “I told the story to my committee about me lying at my first confession and they laughed their asses off.” Then she related her experiences in Vermont.

As a child, Chavez had “loved neon colors and glittery clothing,” but her father would not let her wear such things. As a form of delayed compensation, she “started ‘bedazzling’ some vintage statues.” She “dressed up” the holy images, rather than herself. This is how the installation that became My First Communion began, with works made in parental defiance that had no immediate or clear-cut purpose. Chavez notes that once her installation opened, “many little girls would run to my installation and were love-struck by the colors and sparkles.” She observes: “It makes sense that I was channeling that little girl in me.”

Chavez recalls:

“Most of all I was having so much fun making everything. There were lots of late nights full of drawing and giggling. I felt like I was doing something naughty but it was so exciting, I felt free.”

Weeks before her opening, Chavez’s committee inquired whether she was inviting her parents. She replied: “HELL NO!” When they laughed and inquired further, she “started feeling symptoms of a panic attack.” Chavez adds:

“At the time, just the thought of them reading my texts and seeing my drawings of penises and vaginas [which she placed in florid, heart-shaped frames] was beyond terrifying. I felt they would be ashamed of me. They still haven’t seen those works and I don’t intend on showing it to them. They never really attend my art shows; they feel uncomfortable and out of place.”

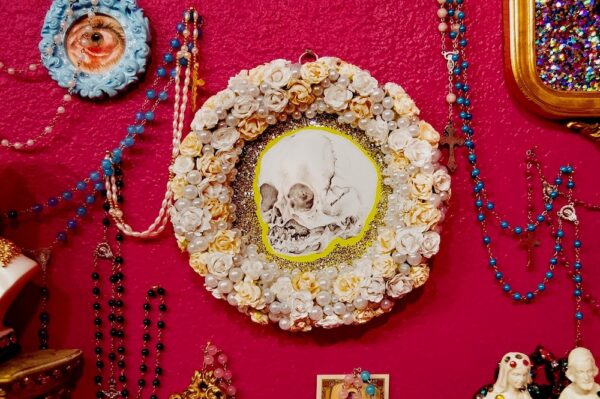

Lisette Chavez, detail with drawings of eye and skull from Three Hail Marys, Two Our Fathers, 2016, Provenance Gallery. Photo source: courtesy of the artist.

By the time she presented My First Confession as her thesis exhibition in 2014, Chavez had overcome many inhibitions. For exhibitions at subsequent venues, she retitled it Three Hail Marys, Two Our Fathers (all photographs in this article are from the 2016 exhibition). It included bedazzled and blinged-up holy (and un-holy) objects, the mysterious and compelling drawings of eyes, tiny skulls surrounded by rows of flowers, framed texts (some of which were questioning or passive-aggressive), and even a few tiny, elaborately-framed details of genitalia. All of these objects were treated like sacred objects in popular Catholicism, enclosed in cheap, often gaudy frames, and sometimes surrounded by garlands of artificial flowers.

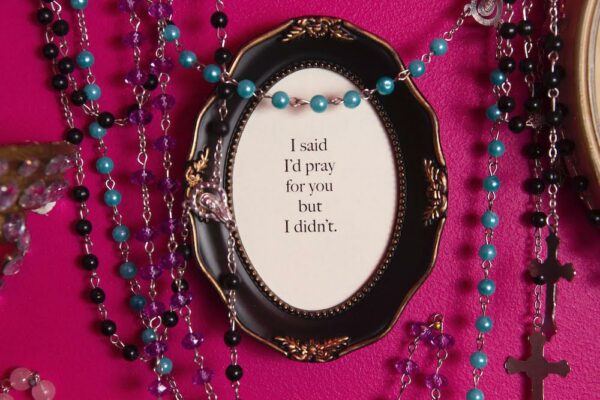

Lisette Chavez, detail of framed text from Three Hail Marys, Two Our Fathers, 2016, Provenance Gallery. Photo source: Alma Hernandez. This text: “I said I’d pray for you but I didn’t,” struck a chord with many visitors, some of whom confessed that they had done the same thing.

I asked Chavez what her professors thought of her installation, and she gave this reply:

“They thought it was hilarious but one told me that I was still holding back and that one day I was going to be comfortable with myself and just let go. I think this comment gave me a lot of hope. It’s a lifelong process to let go of Catholic guilt.”

Chavez added a coda to this comment: “Some people call themselves ‘recovering Catholics.’ Ha ha!”

Chavez’s religious uncertainties had been transmuted into a disparate array of individual objects, whose concrete forms varied as much as their subject matter. In their own unique and specific manners, nearly every object included in the installation broke taboos that Chavez had previously observed. These contradictory objects were all linked together, trapped like a multitude of flies caught in a vast spider web of rosaries. Chavez still didn’t want her family to see the things she really wanted to make, but instead of censoring herself, she “censored” her family—by not inviting them to the exhibition.

Lisette Chavez, Three Hail Marys, Two Our Fathers, 2016

Lisette Chavez, Three Hail Marys, Two Our Fathers, 2016, view of complete installation, Provenance Gallery, San Antonio. Photo source: courtesy of the artist.

As exhibited at the now-defunct Provenance Gallery, then located in Andy Benavides’ art complex at 1906 South Flores Street, Three Hail Marys, Two Our Fathers had the advantage of being compacted into a small, hall-like space that engendered a hallucinatory claustrophobia — or perhaps a cloister-phobia?

Only a few visitors could see it at one time, and you had to look closely because you couldn’t get very far away, even if you tried. The candy-pink walls deliberately invoked — or even screamed — naïve juvenile femininity, an alterity that contrasted with the sometimes morbid subject matter Chavez placed within them.

In his review of the exhibition, Jack Arthur Wood, who knew Chavez through a network of students at A&M, spoke of encountering a meticulous and bedazzling “cluster frenzy,” a “krafty, technicolored, sparklegasm” that “reads like a brutally honest teenage confession that would burn the ears of any priests worth their salt” (“Lisette Chavez’s ‘Three Hail Marys, Two Our Fathers,’” AEQAI, Summer 2016).

In his view, the religious objects, “interspersed with tender sacrileges,” created an effect of vulnerable honesty that was also “keenly sexual.” Like many who have seen this installation, Wood is surprised that Chavez has not abandoned the faith. He observes:

“Chavez goes to church because she loves the intensity, the catharsis, and the ritual aspect. She loves the sound of people praying. She’s somewhat of a Catholic voyeur… she finds it incredibly hard to believe in God when there is so much tragedy in the world. She cannot believe that so much pain is supposed to teach us something.”

In her artistic statement that accompanied Three Hail Marys, Two Our Fathers, Chavez notes that in church and on trips to religious sanctuaries, she was attracted to the ornate ornamentation and the violent imagery that she saw, which she terms “both divine and unsettling.” Her hand-drawn images and her printed texts are intended to communicate “the unease between purity, seduction, and evil.”

Chavez intersperses framed texts among her (mostly) holy images. They are “personal confessions” that imply shame and point out hypocrisy. We’ve already seen “I said I’d pray for you but I didn’t.” “More crosses and more Jesus’s won’t help you or me” is her most explicitly skeptical statement. “Believe in God, Believe in the Devil,” might seem ambivalent, but the church teaches not to take the devil lightly. “I’ve read the Satanic Bible but not the holy one” is not intended to condone Devil worship. Chavez provides this clarification:

“I think that to know God, you must also know the Devil. Most religious people don’t question faith and that’s a problem. I guess it’s taboo, but I wanted to know what everyone was so afraid of. I’d rather not be in the dark about something, I’d rather know for myself. It’s actually stupid and kinda funny in some parts of the Satanic Bible.”

“We only dated because you looked like Satan” reflects Chavez’s mother’s penchant for spotting devils. “When are we going to have the sex talk?” addresses her parent’s failure to provide sexual information to her.

Some texts are more aggressive, such as these: “He whistled and said ‘Hey baby,’ I was six, but I prayed for him to die;” “While you prayed the rosary, I thought about all the times you’ve hurt my family;” “She fucks strangers on Saturday night and goes to church on Sundays.”

While Chavez does not want her family to see this installation, she does not regard it as blasphemous or irreligious. In fact, she told Wood that this body of work “is her direct line of communication with God, if He’s listening.”

Chaves notes that the above quote was in the context of confession. She elaborates her perspective: “You don’t have to go to church to talk to God. I can have faith even if I don’t go to church. And I can confess my sins to God without going to a priest. If He sees everything then why do I need to go confess to a priest? I don’t need to belong to a group or congregation to know I have faith in God.”

Such views are at odds with the orthodox positions of the Catholic church, and led to the accusation that Chavez was a “cafeteria Catholic.”

Lisette Chavez, Cafeteria Catholic, 2017

Lisette Chavez, view of the installation Cafeteria Catholic, 2017, Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, San Antonio. Photo source: Luis M. Garza.

For her culminating project as a recipient of an Artist Lab Residency at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, Chavez created her Cafeteria Catholic installation. The title was inspired by her Tucson professor Angie Zielinski, who told Chavez: “You’re what my grandmother would call a ‘cafeteria Catholic.’ Someone who picks and chooses what they want.” In a cafeteria, of course, you can take just what you want: “I’ll have the pizza, fries, cake, and pie; I’ll pass on the peas & carrots, spinach, and the red beets.” In her wall text at the Guadalupe, Chavez described a cafeteria Catholic as someone who “selects which faith or moral teachings best suit their lifestyle at a given time.”

Rather than leave the church altogether, Chavez picks and chooses the specific articles of faith that she likes best. Chavez also notes that she “was taught to suppress my ideas,” to keep a low profile, and to refrain from dating. Her parents never told her about “the birds and the bees.” Due to her upbringing, Chavez adds: “Accepting my thoughts and being myself is a constant battle.”

Lisette Chavez, Cafeteria Catholic (detail of two veils and crucifix), 2017, Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, San Antonio. Photo source: courtesy of the artist.

As noted in a caption above, Chavez’s imagery frightened her mother, who covered her prints with bath towels. Cafeteria Catholic replicates this experience, but with lace fabric that serves “as a veil to hide shameful thoughts from the judgments of others.” The drawings beneath the veils treat the eternal struggle between Good and Evil, but in the specific terms of the artist’s own moral ambivalence. The transparency of the veils also serves as an invitation for the spectator to look closely at what is beneath them, and ultimately to lift the veils, and, in the process, to “expose” Chavez’s “impure thoughts,” which take the form of drawings, as in the horned figure with the scarred face in the first illustration. Another memorable drawing features a man with a zippered, S&M-style leather mask over his face. She also depicted Christ covered with pimples. Chavez provides this commentary on the drawings:

“I think lots of times people don’t really understand the amount of suffering that Jesus went through for our sins. Sometimes I like to cover him in pustules (I did this with the rhinestones on the vintage statues too), I dunno, I think young people would be able to understand that a bit better because we’re all so vain. One was also a baby devil, which I thought of someone just being damned since birth. Someone who is evil from conception.”

Lisette Chavez and Audrya Flores, Angel Baby, 2017

Paola Cortinas with installation for Angel Baby (the video is being screened above the head of the bed; the Devil-girl has just wiped blood from her victim on her teeth), 2017, bed, bedding, fabric, lights, LED bulbs, LED candles, hardware, and single-channel video, color, sound: 2:50 min, Lady Base Gallery / AP Art Lab, San Antonio. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova.

Audrya Flores and Chavez met at Provenance Gallery. They were both from the Rio Grande Valley, and at one point their conversation turned to their experiences with sexism and machismo. They also discussed folklore, including the story of the “Devil at the Disco” (older people call it Devil at the Dance), a finger-wagging admonition against female “impropriety.” They had heard slightly different versions, but the basic content is the same everywhere. A daughter disobeys her mother, goes out to a dance, dresses and/or dances in a suggestive manner, and — to her belated horror — realizes that her handsome, well-dressed dancing partner is none other than the devil himself, who is revealed by a cloven hoof or a chicken’s foot (or both). She faints, or even dies, and the devil departs in a cloud of smoke and the whiff of sulfur.

The two artists had met shortly after Trump was elected president, and his election and the campaign that preceded it served to heighten their awareness of sexism and sexual harassment. “We started to complain about how unfairly women are treated, even in folktales,” says Chavez. Moreover, as Chavez recalls, “We asked ourselves why couldn’t this girl just go out dancing, why did her mother forbid her to go. Then she just sneaks off to go have fun and ends up meeting the devil. How convenient!”

As Flores told Elda Silva of the Express-News: “When a woman goes out, everything’s examined — what she’s wearing, who she’s with, does she dance, does she not, all these things — and we wanted to examine how that really hurts us.”

The two artists thought critically about the moral of the story, and “how a lot of folklore that we heard in the Valley always comes as a warning to those who are wild and don’t follow directions.” Since folk tales are traditional, they serve to transmit and reinforce traditional values. Chavez recalls that when her mother disapproved of her behavior or attitude, she would tell her: Te va salir el diablo! (the Devil is going to appear in front of you).

Aware of the conservative, women-controlling function that the legend played, the two artists wanted to turn the story on its head, while retaining its supernatural aspects. Flores informed Laura August: “We liked the creepiness of it, but also we were agitated by it” (“Texas Studio: Audrya Flores and Lisette Chavez,” Arts and Culture Texas, January, 2019).

Chavez says the two artists asked themselves, “What would people think if the devil was a woman and not a man?” They sought a complete gender role-reversal. Chavez discussed the terms of their role-reversal to Silva: “I think we’re taking the gaze that’s usually put on women and we’re flipping it back and putting it on the male.”

They started brainstorming. Flores asked who could serve as “our Devil lady.” Chavez recalled a woman she had seen at a recent opening in Austin who had modeled for a mural. She recalled her “beautiful brown skin” and unforgettable features. “I couldn’t stop staring at her at the opening,” says Chavez, who wanted to approach her and compliment her style.

Chavez says Paola Cortinas, her potential candidate for their devil woman, was “elegant, intimidating and so beautiful. I can’t really explain exactly what I thought at the time, I just had never seen a woman like her before. She stood out.” Chavez adds that Cortinas gave the impression that “she had walked right out of a Russ Myers film.” In particular, Chavez thought of Haji.

Haji was an exotic-looking actress, partially of Filipino descent, who played in several Myers flicks, including Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (1965), in which she played one of three killer (literally) go-go dancers. Fittingly, Haji introduced magic and psychedelia into her roles in Meyer’s films.

As Flores remarked to August: “Once we decided the devil would be the woman, we knew she would be really strong, with a kind of vintage vixen vibe, but also… totally intimidating.”

Lisette Chavez and Audrya Flores, film still of female devil played by Paola Cortinas from Angel Baby, 2017. Photo source: courtesy of the artists. The film works through implication. The she-devil’s horns, for instance, are shadows.

During their conversation, Chavez showed Cortinas’ Instagram account to Flores, who enthusiastically agreed with her assessment. They assumed that Cortinas probably received “tons of messages from wacky admirers,” so they gathered their credentials and work samples “in a very professional email” that they submitted with fingers crossed. Cortinas responded that she had never acted before, and that she did not want to ruin their project. Chavez notes their response to Cortinas: “We told her we had never made a film before so we were going to learn all of this together.” Chavez concludes: “And we did!”

The project came about through the invitation of Sarah Castillo of Lady Base Gallery, an itinerant gallery-without-walls that exhibits women artists. The AP Art Lab (in the same South Flores complex as Provenance Gallery) physically hosted the installation.

The film was projected through the frame of Flores’ white canopy bed, which is a family heirloom, in a small room aglow with red light. The sugary-sweet vintage classic Angel Baby (1961), written by Rosalie Hamlin and performed by Rosie and the Originals serves as the film’s soundtrack.

The Devil-woman is in a club, where she exercises her ability to stop time. Chavez describes how she inspects the men, who are frozen in place: “While the men in the club are frozen in time, she walks around them, she starts hunting, smelling them, and touching them, trying to choose which man will be her victim.” She starts time up again and approaches her designated man. She takes him by the hand and they begin dancing. Unaware that he is playing with fire, the man feels her rear end, which, as Chavez explains, the Devil-woman permits “only to let it fuel her anger.”

The Devil-woman embraces the man tightly. The camera turns to his face. He now clearly feels the woman’s power. He is terrified. He begs for his life, but she strikes him dead. This filmic action stands in ironic contrast to the lyrics of the song that serves as the video’s soundtrack:

“When you are near me, my heart skips a beat

I can hardly stand on my own two feet.”

She sneeringly looks down at her victim — as Chavez puts it — “as if he’s a piece of garbage.” The club-goers flee the scene.

The camera turns back to the woman’s striking face, which is calm and perhaps satisfied about a job well done. The Devil-woman reverts to an image more in keeping with the angelic innocence described in the song:

“It’s just like heaven being here with you

You’re like an angel, too good to be true.”

Lisette Chavez, Paola Cortinas, and Audrya Flores with installation for Angel Baby (the Devil-woman is sniffing one of the men in the video playing in the background), 2017, Lady Base Gallery / AP Art Lab, San Antonio. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova.

Chavez noted to August why she thinks the film is important, for the filmmakers themselves, and for women in general:

“It’s kind of like unlearning all that good-girl stuff and becoming your own person. We needed it. And from the conversations we’ve had, we realized other women needed it, too.”

Chavez reports that her mother also enjoyed and approved of the video: “She understood our concept and was kinda excited that the woman was going to be the one who was empowered and not weak. She said she had never seen anything like it in her life.”

Lisette Chavez, From the Horse’s Mouth, 2021

Lisette Chavez with From the Horse’s Mouth installation, 2021, Palo Alto College, San Antonio. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova. Chavez is turning the crank on a rotisserie coffin.

This body of work had its origin when Chavez was at a packed restaurant with her late husband Craig. At one point, she noticed that no one else was talking because all of the other diners were scrolling on their smart phones. On the drive home, she reflected on dinners during her childhood, which were always accompanied by her mother’s “scary folktales.” Chavez relished her mother’s stories, though they were a continuous source of sleep deprivation. She worried that human interaction, folklore, and oral family histories were being lost to technology. From the Horse’s Mouth is an exhibition that was created to depict and preserve those stories.

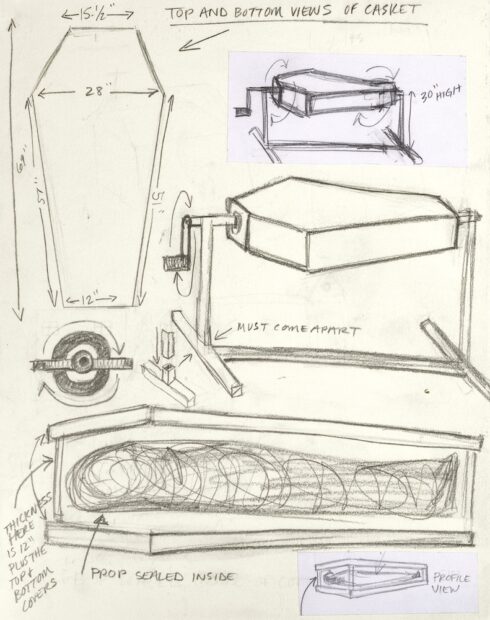

In the installation shot pictured above, Chavez is turning the crank on a piece called Heaven or Hell (2020), which is essentially a rotisserie casket. As one rotates it, one hears the pleasing thuds of the artificial corpse that has been placed inside of it. This sculpture was inspired by a story Chavez’s mother told her. She said that once the deceased was buried, if the corpse’s soul was destined for Hell, the casket would flip over, so that the body would face Hell rather than Heaven. To see the casket in rotation, go here.

In her drawings, Chavez mapped out every detail.

From the Horse’s Mouth is the only exhibition since her Early Mourning installation that Chavez showed to her mother. The Horse’s Mouth work was in Chavez’s living room, in preparation for a museum studio visit, when her mother came to town.

On that day, Chavez achieved some payback, an experience she recounts with glee:

“You should have seen my mother when she cranked the coffin, it was hilarious! She was terrified and jumped when she heard ‘the body’ tumbling around inside.”

Chavez notes the ironies of this dynamic of inter-generational fear: “It’s funny because my mom thinks that a lot of my work is terrifying — but she’s been scaring me all of my life. Not sure how she hasn’t realized that.”

Chavez’s mother was excited to see the illustrations for Horse’s Mouth, which she judged the artist’s best work. “I think, for once, she understood why I create these bodies of work and how I can connect with the audience,” says Chavez. It is a body of work the artist’s family can relate to, which is not surprising, since family stories provided the basis for every work in it.

I asked Chavez how she feels about these stories today, and she says, “I think that the stories my mother and father have told me are true. Part of me tries to rationalize what my folks are telling me as I’m hearing it, but my body has a very intense and physical reaction. Many times I’ll feel terror wash over me or I get goose bumps.”

Chavez says the stories have “definitely contributed to my love of horror.” In fact, she thinks that the horror genre and Catholicism have much in common:

“I love watching horror movies. I once read that people with a lot of anxiety like watching horror movies because for once they can relax and watch someone else writhe in anxiety and pain. Ha, ha! Sounds a lot like Catholicism! I think it’s strange to be in worship, look up, and see the emaciated body of a man who is bloody and crucified. There are images of him being whipped. You see statues like Our Lady of Sorrows with swords in her chest. So much of the imagery that you see in church is often violent and dark. Someone without the same type of faith would walk into a Catholic church and find it disturbing. I think many parts of seeing things in church are like a horror movie. There’s so much talk about the body and blood, pain, seduction, I could go on and on. You might as well be in a horror film while you’re in church!”

Lisette Chavez, Haunting, Offering, Accident, 2020, graphite on paper, 14 x 17 inches (each). Photo source: Beth Devillier.

This triptych was inspired by a story known as “The Woman in White.” The following is Chavez’s recounting of the tale:

My great uncle used to get intoxicated and go to a wooded area nearby my grandmother’s home, it was called El Champion. One night, he pulled up to the woods and got out of his truck, he had a feeling that there was buried treasure at this location. As he walked away from his truck, he said an Indio (Indian) appeared in front of him and told him to turn around and not take another step forward. He disobeyed the Indio’s orders and kept walking towards a large tree. It was then that a woman in white appeared in front of him, he noticed that her feet were not touching the ground.

She was wearing a long apron and lifted it, to reveal a significant amount of shiny coins, he said that they shimmered in moonlight. He told the woman that he would come back tomorrow to pick it up and went back to his truck. He quickly went to visit my grandfather to tell him what had happened at El Champion.

He went back the next day to claim his treasure but there was nothing there. After a few months had passed, the lady in white started coming to his bedroom window, where she would watch him through the glass. He asked his wife to sleep next to the window because he was terrified of this ghost. The woman in white haunted my great uncle for the rest of his life.

One night, him and his friends went to Mexico to drink. They crossed through the border and drove on a long highway back home to the Valley. It was about 10 p.m. and his friends said that they saw a woman in white appear in front of the windshield. My great uncle screamed and swerved the wheel, his truck drove down an embankment, where the driver’s side door opened and his body was severed in half between the truck door and a tree.

Lisette Chavez, Undying Jack-Rabbit, 2020, graphite on paper, 14 x 12 inches. Photo source: Beth Devillier.

This tale of supernatural hunting/haunting is also situated in the vicinity of Rancho Champion. Chavez’s family hunted rabbits late at night, when they came out of their holes to forage. Chavez says this particular rabbit “would jump back and forth when they would shoot at it, almost as if it was playing with them.” Family members were certain it had been hit multiple times, yet it refused to die. Chavez’s mother testified that the rabbit made the hair on the back of her neck stand up, which she interpreted as a sign that “the rabbit was evil.” She also noted that the infernal rabbit often showed up around midnight, which further confirmed her suspicions.

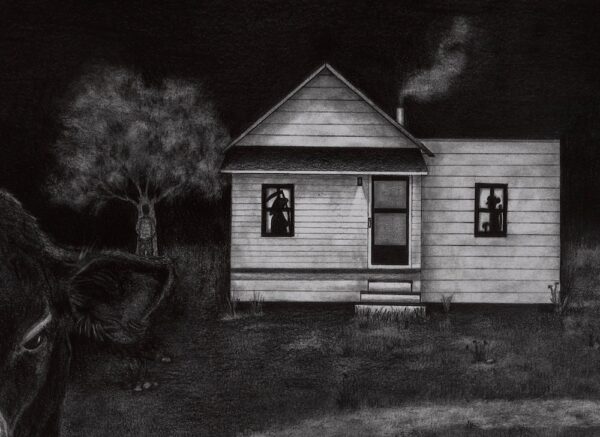

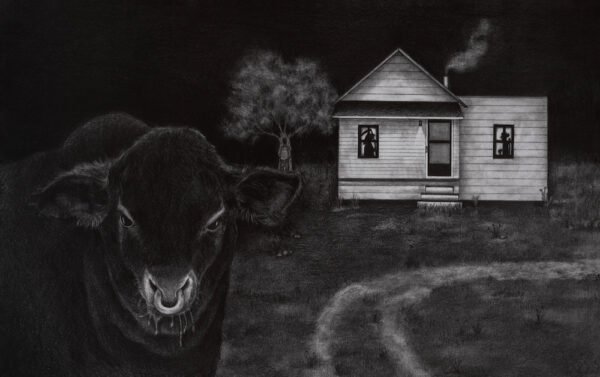

Lisette Chavez, detail of Grandma’s Final Days, 2020, graphite on paper, 13 x 20 inches. Photo source: Beth Devillier.

Chavez narrates this story:

My maternal grandmother was near death and my mother and father went to stay at her home one night. It was sort of out in the country. At one point my father had to use the bathroom but it was occupied so he went outside. It was midnight and he was standing by a tree urinating when he heard a large animal breathing heavily behind him.

Lisette Chavez, Grandma’s Final Days, 2020, graphite on paper, 13 x 20 inches. Photo source: Beth Devillier.

Chavez continues her story:

He turned around and saw what he described as a black bull with chains wrapped around it. He completely freaked out and ran inside, my mother said that his eyes were the size of eggs and he was pale and frightened. My father mentioned the bull and my mother quickly ran outside to look for it. They looked everywhere but never saw it. The next morning my parents went to visit my grandmother in her hospital room and my mother asked her how she slept. My grandmother replied, “I couldn’t sleep all night, there was a black bull that wouldn’t leave me alone.” My mother thought that the bull was evil and it’s mostly because my father saw it around midnight. She’s still not exactly sure what it was.

Note that Chavez’s grandmother (who was not even at the house that night) is in silhouette, seated in a chair, as if she were expecting someone. Death, in the form of the grim reaper, is silhouetted in the other window. He is presumably coming for her. If you are in this neck of the woods and you have to pee outside, it might be a good idea to do it before midnight.

Lisette Chavez, He Always Wins, 2020, graphite on paper, 19.5 x 19 inches. Photo source: Beth Devillier.

Chavez again serves as our narrator:

My paternal grandfather used to play poker with his friends and there was one man in particular who always seemed to win. On one evening, my grandfather pulled this man aside and asked, “how is it that you always seem to win?” To which, the man turned around, with his back facing my grandfather. The man slowly unbuttoned his shirt and pulled it down. It was then that my grandfather saw a large tattoo, a portrait of the Devil himself. The man turned to my grandfather and said that he sold his soul to the Devil.

It seems that it is all aces (and royal flushes) when the Devil’s got your back! Chavez sourced this image from photos of vintage tattoos. She reproduces her direct model in the catalogue. The basic form of this tattoo closely follows her model, though Chavez has added bands of light and dark areas that are almost as emphatic as stripes. Her Devil’s eyes, forehead, hair, and the flames beneath him are much more complex than her source tattoo, which is more like a simple line drawing. Her devil’s hair has a flame-like aspect, which seems like a dark variation of the emblematic flames situated beneath his head. Curiously, Chavez has given her Devil a cleft chin instead of a pointed one.

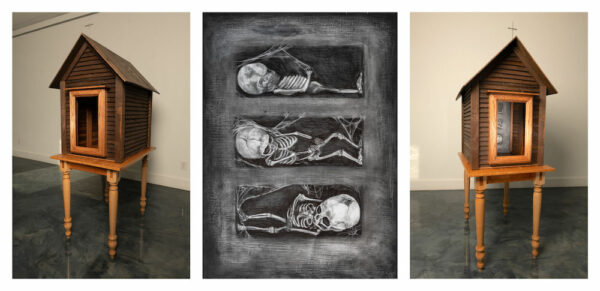

Lisette Chavez, Convent of Secrets (two views of structure and the drawing in its interior) 2020, wood, steel, with graphite on panel, 68 x 24 x 34 inches. Photo source: Beth Devillier.

This story’s transmission is the most convoluted, and not much is known, except the most basic facts. Chavez tells it this way:

My great uncle on my maternal side worked construction and demolition. One particular day he was called out to a convent in Brownsville, Texas. I don’t know the name of the convent but while he and his crew were tearing down the building, he saw what appeared to be fetal skeletons behind the boards. Nobody knows where those babies were from or who they belonged to, but my great uncle told my grandfather, who told my mother.

Chavez sourced the small structure from grave markers for children that are made out of wood and resemble dollhouses. It is her final resting place for these fetal skeletons, represented in the form of drawings.

Lisette Chavez, Reaper’s Call, 2020, graphite on paper, 9 x 12 inches. Photo source: Beth Devillier.

Chavez’s mother says that when dogs howl at night, death is afoot… .

****

All uncited quotations in this article are from communications between the author and the artist, September 23-27, 2021.

The exhibition “From The Horse’s Mouth” is on view at Palo Alto College, Fine Arts Gallery 100, Concho Hall, through October 14, 2021. A fully illustrated catalogue (including sketches and source material) has been published, featuring an essay by Bianca Alvaraz and an interview with the artist by Liz Paris, curator of the exhibition.

****

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian who has curated more than 30 exhibitions. His last exhibition and catalogue was ‘The Day of the Dead in Art’ (Centro de Artes, San Antonio, 2019-2020).