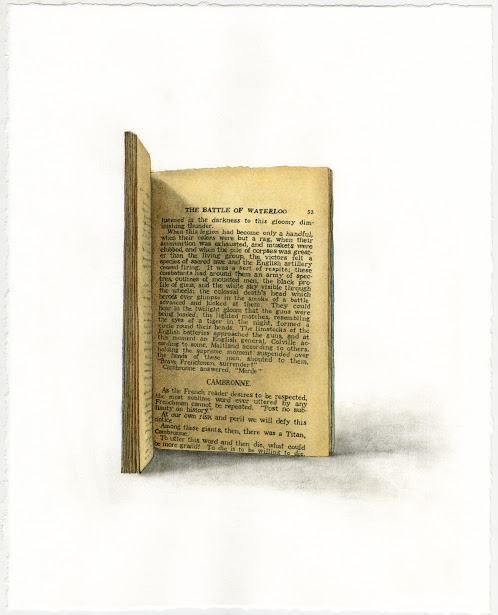

Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo paved the foundation for our modern world: from British hegemony to German nationalism to ABBA’s 1974 number one Billboard single recounting a woman’s surrender to the pursuits of a persistent suitor. Painter Angela Kallus’ Reading Room show Waterloo in Dallas makes a smaller splash, surely, but is no less stratified in its narrative weave. Both radical and mundane, the show features a series of book portraiture (you read that correctly — these are portraits of books), drolly sequenced and hung per the artist.

Kallus’ work here leaves us a trail of breadcrumbs to universal concerns like sex, jealousy, conquest and religious oppression without ever leading — leaving audiences to spot connective tissue as they thematically see fit. The artist utilizes an initially random-seeming sequence drawn from her growing collection of Little Blue Books (more on those in a minute) to not so much glimpse her own interior as to make some conspicuous jokes. Gallery visitors will likely find themselves transfixed by Kallus’ books’ poses and their play on texture and realism. But beyond tactile display, following Waterloo’s narrative threads can be dizzying. “I went down the rabbit hole,” Kallus admits. With all its literary references, landing on your own read may feel random — a loaded motif the artist calls “the floating signifier.”

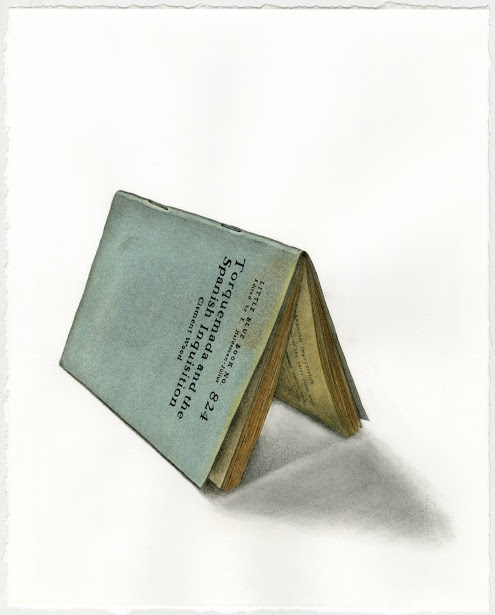

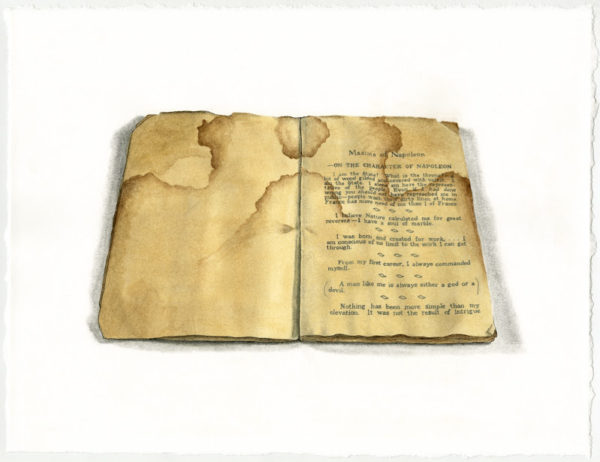

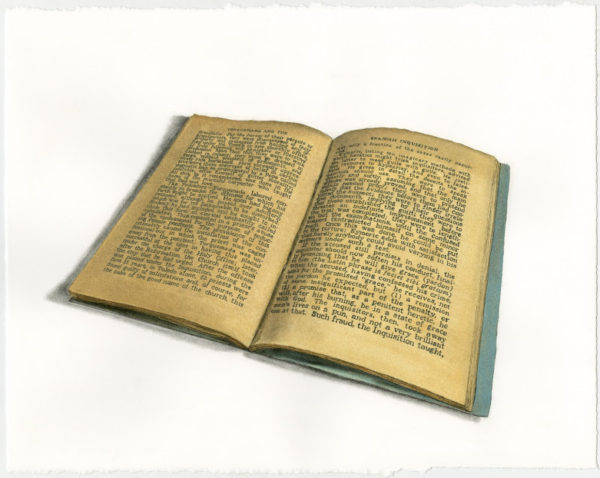

Kallus lives and paints in Fort Worth and is a professor at the University of Texas at Arlington. Beloved by fellow artists and educators, she nestles nicely into the Reading Room’s unofficial for us by us programming. For all the care and concern that went into her selection of texts like Salome and Torquemada and the Spanish Inquisition, Waterloo’s implied literary bent is a bit of a red herring. Message succumbs to method, considering the strength of the show’s vibrantly replicated typeface. Technique is the star. Kallus knows this. A line from Soul of Marble, her recreation of the Maxims of Napoleon, reads:

I believe Nature calculated me for great reverses

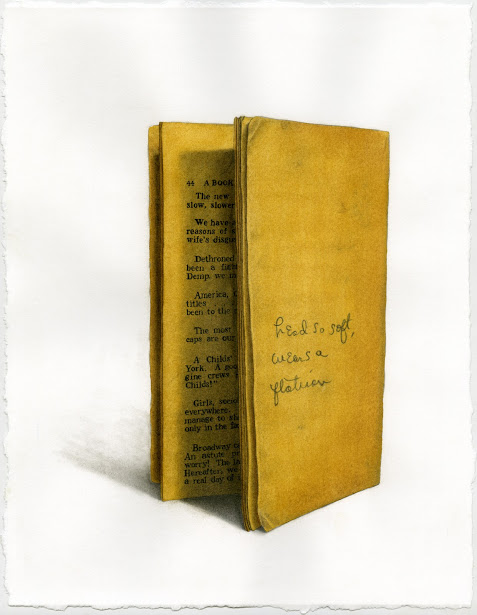

I do love puns. Re-verse. Get it? Kallus sees herself accurately, for her hand is ever-present, and all fonts’ deceits are designed to crumble, if ever work at all. Above dealing only in visual tricks, but not quite game for overt stylization, few of her images appear real. Instead, Kallus bends each letter to her will (copying typos, perhaps adding a few of her own). There’s no questioning Kallus’ weird knack for forgery. In We Have Dethroned America she recreates, at an angle, a handwritten note scrawled on the back of A Book of Broadway Wisecracks — a bonus joke deemed legit enough to ride along. Exposed text peeks from behind shielding pages, revealing to viewers a mere glimpse of its interior intentionally — playfully, incompletely. In this minutia, Kallus shows us what attracted her to this still life. Her Little Blue Books are covered in original owner’s notes and Rorschach-ian coffee stains; others are ripped, faded, and worn with age. They all teem with ghosts of previous ownership.

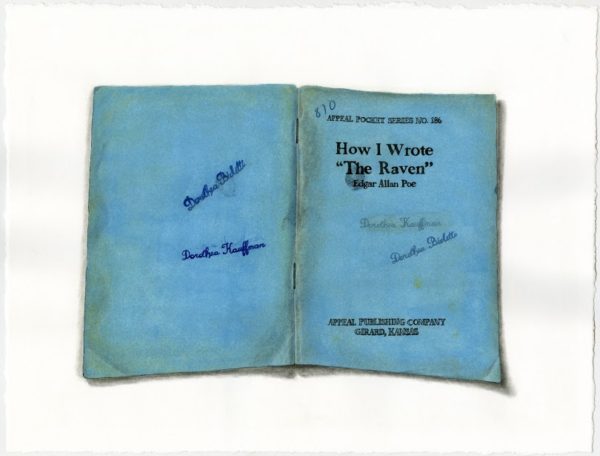

Every paperback in Waterloo comes from the same place: Girard, Kansas, where hundreds of millions of these Little Blue Books (not all were blue) were published by the Haldeman-Julius Publishing Company during the mid-20th century. A Jewish-American atheist socialist, Emanuel Haldeman-Julius produced excerpts from some fairly conservative-leaning texts — and this is editorializing — many in Waterloo seem selected for their subversive content.

Kallus painted her first Little Blue Book, a Nietzsche snippet titled Guilt and Bad Conscience, in January this year as an exercise, but became fascinated by the extensive library (numbering in the thousands) and has since amassed a collection. In one of her portraits, text from Oscar Wilde’s Salome comes as a most common cry of our times — to be able to face your accuser and have your say. Speaking to John the Baptist’s severed head:

Thou rejectedest me. Thou didst speak evil words against me. Thou didst bear thyself toward me as a harlot, as to a woman that is a wonton, to me, Salome, daughter of Herodias, Princess of Judea! Well, I still live, but thou art dead, and thy head belongs to me. I can do with it what I will.

Every book holds capacity for a second life. Like its owner, it may fall on the receiving end of neglect, abuse, obsession and indulgence, and yet be full of power and latency, too. Here in Waterloo, surface scars tell stories more befitting portraiture than content writ upon pages. These paintings’ material nature is deeply seductive for viewers. But Kallus brushes aside questions regarding her subjects’ uncanny allure: “It looks like paper because it is paper.” Oh, right. Nice trick.

On one level, Waterloo recalls Valeska Soares’ 2007 series Love Stories. For those works, Soares created a library of dozens, sometimes hundreds of books on shelves, that, despite their beautiful linen binding, are full of blank pages. Love Stories isn’t really about books at all, but about selection of references intended for proliferation by the artist. Now, using René Magritte’s notorious The Treachery of Images as a cipher, I can land on what bugs me about Waterloo.

Books are a new avenue for Kallus, who is previously known for sprawling depictions of roses that are similarly tactile and sensuous. Many correctly presumed the roses could be stand-ins for genitalia with their labial-like folds. Kallus admitted as much to me:

AK: That’s what I’ve been interested in with my other work. Roses that aren’t really roses.

CM: Vaginas?

AK: Sure. All kinds of things… . Some people see frosting on a cake. I can’t tell you how many people walk up at an opening and say, “I wanna lick that.” Deadpan. Not ironic. Middle-aged women.

Given the similarly allegorical designations of an open book, Kallus risks boxing herself in with this unexpected but logical expansion of her oeuvre.

I cannot outright enjoy Kallus’ Waterloo. It’s slick and mercurial; its revelations do more to obscure than reveal the artist under a bevy of winks and calculated brush strokes (or pencil lines). But that’s okay — some alienation appears to be a built-in facet of the show. These aren’t books. There’s nothing to pick up and digest, and yet each picture is made to pull you in. This produced in me a yearning the works could not and would not satisfy. But the image of the thing is not the thing shows rule, and are essential in today’s image-saturated society.

Waterloo is one of those shows. Confidently subjective and demonstrating deep affinity with craft, it elicits for this reviewer an insurmountable awareness of my own ignorance about painting methodology, which probably plays into Kallus’ artist-educator prerogative. A kind of Mona Lisa smile. Confronting feelings of “missed opportunity,” as opposed to a more pointed narrative (as such text-heavy art can do), Waterloo shrugs off that responsibility, asserting that the politics of the individual are timeless.

Through Dec. 9 at the Reading Room, Dallas.

1 comment

A proper review of a proper exhibition. Well done.