Like it or not, a great number of contemporary artists find their language and their subjects within art itself; artists channel their predecessors through formal languages and material choice, sometimes as commentary or iteration, often directly appropriating certain works or performances. Mordants, an exhibition of new and recent work by Mason Bryant, a recent graduate of TCU’s MFA program, finds Bryant assiduously exploring his own relationship with specific figures in art history in an attempt to find new meanings, and perhaps challenge the old ones.

Mordants, at the Reading Room in Dallas, contains four distinct works which to various degrees contain the spectral presence of other artists’ works. The focal point of the show is a piece titled Without Breath, a digital projection of Chris Marker’s 1983 film Sans Soleil, or Sunless, here stripped of sound and visuals. The only thing Bryant leaves are the English-language subtitles. It’s a meditative, pleasant piece, one viewers are, like much video-based art, meant to spend more time with than most people actually will. As a single work of art the piece operates on multiple levels—there’s the uncertainty inherent in subtitles titling blankness—and then there’s the renewed reckoning with the original film itself, which is Marker’s unreliable travelogue of sorts, his exploration of time, truth (or its absence), and the meaning one can assemble from seemingly disconnected memories.

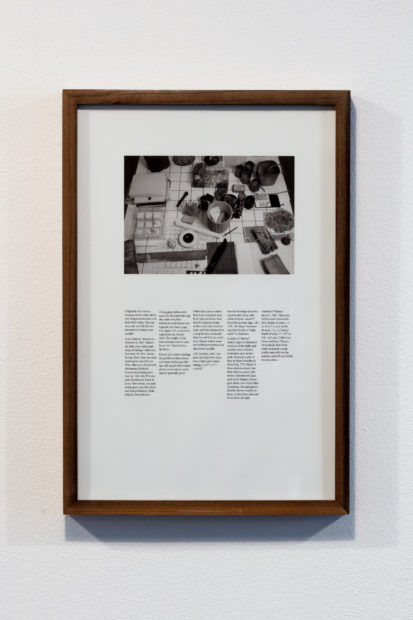

Mason Bryant, The Table in Hesse’s Bowery Studio, photograph initially attributed to Hermann Landshoff, recreated by Mason Bryant, and documented by Daniel Martinez, 2015. Digital prints.

On the wall opposite the projection are four framed images with text. The frames house four photographs taken from the four different sides of a table filled with an array of artist tools and ephemera. A cursory read through the exhaustive notes that accompany the images tell the viewer that the tabletop belonged to Eva Hesse and the photograph was taken in her Bowery studio by one Hermann Landshoff, ostensibly for a book Mel Bochner at one point planned to publish on the subject of artist studios. The notes are culled from various sources, presumably by Bryant, and appear alongside (and indistinguishable from) what one also assumes are Bryant’s own descriptions of the items on Hesse’s table. But the photographs, archival though they may appear, are not Landshoff’s photos but those of Daniel Martinez, a friend of Bryant’s, who documented a recreation of Hesse’s tabletop Bryant made in his own workspace. According to Bryant, all of the items present in the photographs on view at the Reading Room were either re-created or purchased strictly following “all available documentation” of Hesse’s studio and table.

Mason Bryant, Tattoo received with pigment extracted from Yves Klein’s ‘Table Bleue’ tracing the thoracoepigastric, periumbilical, to the superficial epigastric veins, Jan. 6, 2017. Digital video, dimensions variable.

Also on show in Mordants is a short film of Bryant being tattooed in a path along his torso, and several prints of the final product. Again, the work is incomplete without the knowledge, available in the image sheet that accompanies the exhibition, that the pigment used in Bryant’s tattoo was extracted by the artist from one of Yves Klein’s Table Bleue, which a colleague of Bryant’s (both work for an art installation company) harvested after installing one of Klein’s tables in a client’s residence. There’s also a note regarding the veins traced with the tattoo. The path the tattoo takes is, unsurprisingly, itself a reference to Klein. Bryant cites Klein’s notion that the trunk of the body (shoulders, chest, stomach) contains “the presence of the entire body,” and notes that the path of veins the tattoo traces can, albeit with difficulty, be seen externally. The tattoo highlights, at least temporarily, an intentional and predetermined path along Bryant’s body.

In Bryant’s use of the term, the ‘mordants’ of the show’s title refer to the chemicals that combine with dye to “permanently adhere to fabric or tissue.” Of course that very permanence is the thing that Bryant seems to be challenging in his recontextualization of the work and material of others. He refers to the new forms he creates from the language and lives of other artists as the result of a kind of alchemy—Hesse and Klein combining with Bryant to produce something new. By tattooing himself along a Klein-esque path with Klein’s pigment, and by painstakingly recreating the tabletop of Hesse, Bryant seems to be exploring ways in which he can and does have a relationship with artists long gone or inaccessible while at the same time attempting to escape from his experience of their legend or the influence of their work on him.

By taking pains to incorporate physical remnants or pieces of the earlier works and juxtaposing them with his own presence, Bryant is also critiquing the tendency to remove the artist in mid-20th century art. Bryant reveals himself, in the process, as a product of a very different art world, one in which the subjectivity of the artist seems to be the only thing that matters.

The first work mentioned, Without Breath, predates Bryant’s other work in the exhibition by several years and seems, as a conceptual departure, to serve a different role in our understanding of his work. Sans Soleil is about a lot of things, but throughout that original film, Marker uses the images he has shot and the experiences he has had to challenge our notion of agency: Could it be that he isn’t shaping the images but that the images are shaping him? Isn’t it true that we are nothing more than the memories we have and the images we see? For Maker, our truth is only found in and through the reflection of others, and we can’t really nail down an objective truth in the end.

Perhaps the stripped-back Marker film is present as a key to the experiments that surround it. Bryant is aware, like Marker was, that the key to our individual truths often lies in other people and other things, in the experiences we have through the people who formed us. For Bryant the artist, his truth is found in the artists whose work influenced him, and by using their voices in his own work, he can find and reveal himself. Bryant understands that those who came before us formed us in ways we’ll never escape, but that doesn’t mean we can’t evolve past that experience of myth, to create and be something new.

Through Feb 11. at the Reading Room, Dallas. Photography by Kevin Todora.