In an era when white maleness couldn’t be more problematic, Darren Jones’ Nine Inch Will Please a Lady: Romance and Ribaldry in the Literary Vernacular of Scotland, currently on view at the Reading Room in Dallas, is a reminder that a thick accent goes a long way. Barring a few pieces, the show is comprised of text-based works and, almost unbelievably, poems.

As Jones, a Scot, finishes up his residency at CentralTrak this month and bids guidbye to Texas, Nine Inch offers up a lens of myth by which the artist fords the “selective decay” of his memories of Scotland, a place he hasn’t called home in two decades. Influenced by the textual works of Dennison-born artist John Wilcox, Jones set out to unpack the unlikely similarities Texas shares with Scotland. The resulting show is a loving, if indirect, ode to the blue-collar folklore of Texas. Jones explains:

Both regions share an off-kilter sensibility within, or chafing against, a larger political union (Scotland/UK – Texas/US) and have a determination to retain individuality even as part of a larger whole, [having] had similarly traumatic relationships with their borders, and ruling entities.

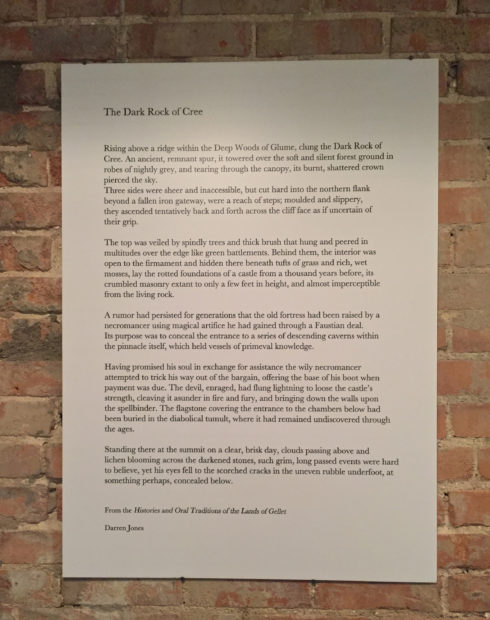

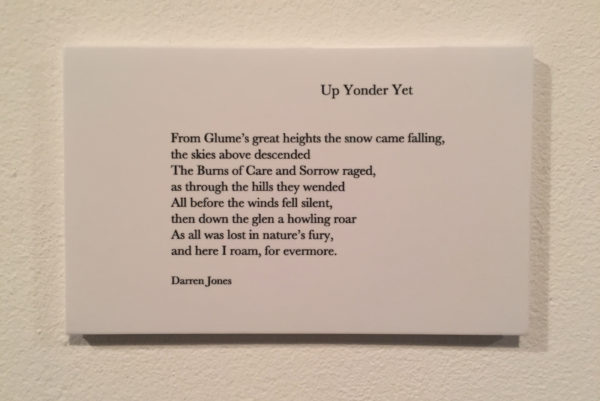

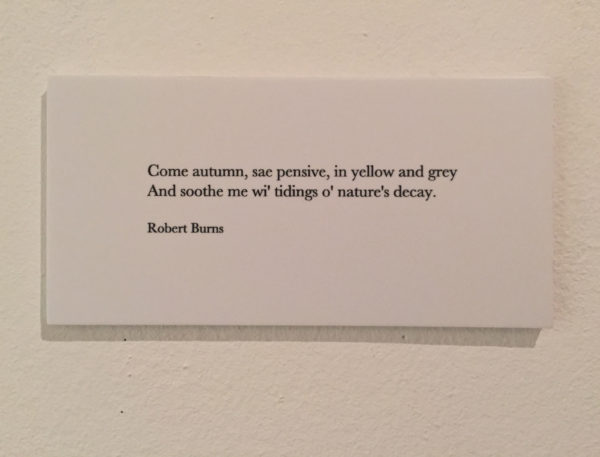

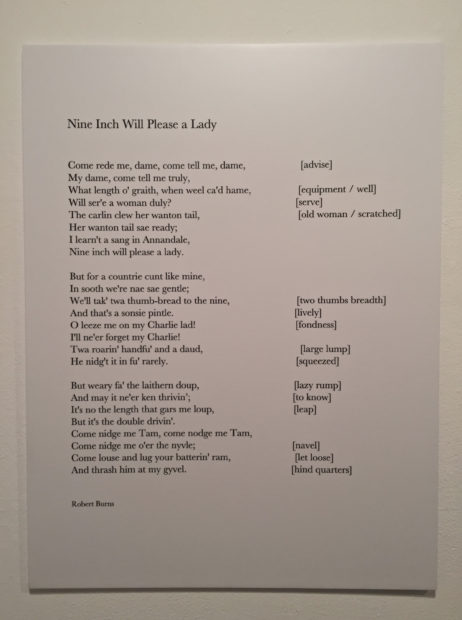

For those worried they are about to stumble into a glen of Scottish nationalism, fear not: Nine Inch never goes full bagpipes. From Faustian bargains to autumn leaves to good old-fashioned fucking, Jones’ show affects a cheeky, hearth-y vibe. The artist’s own poems hang alongside those of 18th-century Scottish farmer-bard Robert Burns, who has clearly influenced Jones’ cadence and vocabulary. Crumbling towers and cresting waves, necromancers and bawdy barmaids feel right at home here. This is the same country that gave us J.K. Rowling.

Earlier this year, Glasgow-based director David Mackenzie demonstrated an easy penchant for Texan swagger with his film Hell or High Water, but Jones’ show attempts something more difficult that demonstrates why international art is so important here in Dallas. The work is always about Texas, even when it isn’t.

This binary read translates to audience reception. Likely many will feel they can’t leave the gallery without reading the lot in full. Others may skim the text, at best. When faced with an awareness of time and public space (versus leisurely reading from a book), how do the poems change? Casting light on the role writing plays in the assembly of narrative in visual art, Nine Inch is also a literal assembly of different narratives—questioning how we engage with works and what they ask of us.

What Jones does with text in Nine Inch feels radical, particularly in comparison to his previous output. Though this show includes a photograph, a drawing and sculpture/found objects, these remain fairly separate and discreet from other textual elements (save for Interstellar Medium’s labels—which exemplify Jones’ words as actions coda found below). It marks a break from his earlier graphical work.

Nine Inch flirts dangerously with coffee-shop art heedlessness. The audacity to hang (admittedly exceptional) poems by a local bard next to those of an international treasure is an age-old democratic trick; it broadcasts ego and the lack thereof in tandem. This is the knife-edge Jones walks, breaking taboos with the grace one could expect from a show regarding cocksmanship. And it underlines the status quo all artists face, in that they cannot expect to display work without some semblance of risk.

In Michel Focault’s The Order of Things, the philosopher finds precedent for implementing similar institutional critiques of both visual art and literature during the Renaissance. Per a kind of “holy-trinity” thinking of the day, the two forms could each be divided into three parts. Firstly discernable are the markings or text of the work. Above the work exists all discourse concerning it and below lies its meaning.”

Art has always assumed a post-language ability to communicate (after it was pre-language, amiright?), but how do works hold up after ditching the “post” pretense? Jones doesn’t quite equate writings with art, but the nod to it is disturbing. In short, it seems lazy to hang a poem on a wall. Doesn’t the artist keep the writer in check, and vice versa, or are they both incorrigible? Jones is aware of this balance.

Among those whose lives 2016 has claimed is text-based Serbian artist Mladen Stilinović, whose anti-capitalist manifesto In Praise of Laziness could hang on the bathroom wall of any creative anywhere, like some miniature Zizek Buddha. Stilinović writes:

Laziness is the absence of movement and thought, dumb time—total amnesia. It is also indifference, staring at nothing, non-activity, impotence. It is sheer stupidity, a time of pain, of futile concentration. Those virtues of laziness are important factors in art. Knowing about laziness is not enough, it must be practiced and perfected.

Looking at a blank page and looking at a blank canvas is the same idea. Anyone who knows knows the agony of composing poems comes with a almost certain risk of failure, unless, like Jones’ poems, they are splendid. Sometimes, you get nothing and are stuck writing about your dick. It’s something.

Landscapes like those around Marfa, Texas or Loch Shiel, Scotland beg for imposed narrative. But Nine Inch Will Please a Lady has more on its mind than ruddy rocks, and Robert Burns is the lynchpin. Burns’ bawdy poem of the same name reads like Seamus Heaney’s Beowulf by way of Brazzers—demonstrating that a crudeness even amidst the Scottish Enlightment formed a core of the country’s identity. Burns died twenty years before Victorian-era puritanism encroached on the franker sexuality of his time (which Focault also addresses in History of Sexuality). A true poet, his funeral was held the day his son was born, but his inclusion in Jones’ show owes more to nature than to Nature.

The poor ploughman’s prose has proudly landed on the perfect cock length because it isn’t afraid to ask for a woman’s perspective. Well done! But Nine Inch is still written by a man (a tiller of soil no less) and is, at its core, seeking of approval. Burns’ mood is more jovial than contemporary inch-obsessors, and freer. Keen to pry apart labia and wanton tail, Burns earns a place in the Room for his inclusive gaze—his pen lets loose cries for Charlie and Tam (Thomas), who gleefully prod legit ‘battering ram’ into ‘countrie cunt.’

It’s hard to critique the work of an artist who moonlights as an art critic, particularly one who delights in language, as he can preempt bad press (by design) and shore up the best vocabulary. Jones has said before that words are actions, which goes a long way in explaining both the transportive and familiar aspects of his show.

Nine Inch’s cardinal sin is that it is nice. Moving into the holiday season, it warms like a glass of whisky or roaring fire. Poetry is not having a moment. Some people think it died twice last month. Perhaps, after some of the liberal self-loathing passes and Jones is long gone from Texas, his Nine Inch will ram home.

Through Dec. 10 at the Reading Room, Dallas.