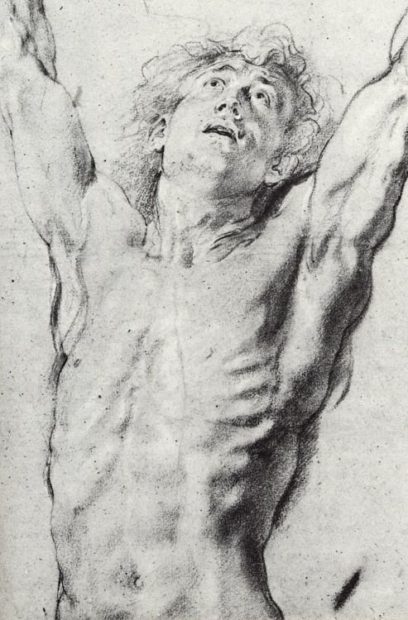

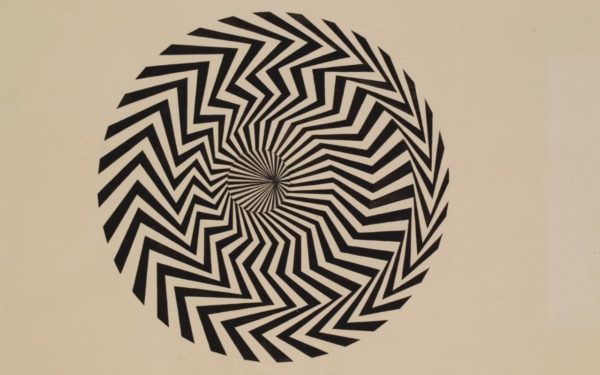

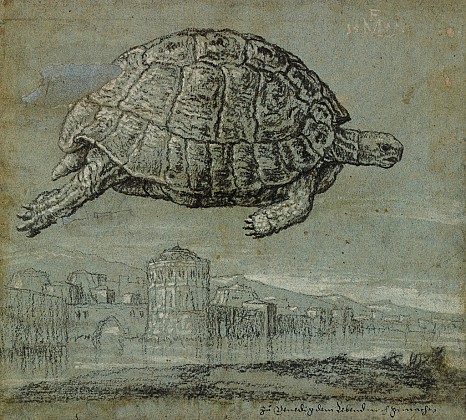

Christina Rees: I was in Santa Fe earlier this summer and caught a show at the New Mexico Museum of Art that blew me away. I’m still thinking about it. It’s called Lines of Thought: Drawing from Michelangelo to Now. It’s all drawings by some of the greatest artists in history, from the 15th century to today. From Leonardo da Vinci to Dürer, Rembrandt, Degas, Julie Mehretu, Baselitz, Bridget Riley. It’s not a huge show, and it shouldn’t be, but it was so good it hit me like a narcotic. Sketches, studies, all these marvelous, intimate works on paper, with the artists’ hand very present in all of them. There are da Vinci drawings that are so alive and immediate it feels like he sketched them yesterday.

It’s my job to look at art, and even I forget how crucial drawing is, or at least was. It feels like drawing has slipped down the ladder of importance as an artist’s tool or process. Or has it?

Michael Bise: It hasn’t slipped down the ladder with any of the artists I care about. Coming to grips with drawing is the beginning of the line for anyone who wants to call themselves an artist. There’s just no other entry point. It’s what the first humans to make art did.

Something that a lot of people tend to forget is that people don’t become artists in college or graduate school or at some other indeterminate point when it might seem fashionable. Artists learn if they’re artists when they’re kids. Some are builders, some are drawers, the best are both — but if you don’t get a handle on the kind of attention to plasticity involved in the close attention to drawing when you’re pretty young, you’ve got a lot of catching up to do. Neuron death and all that.

Drawing is about recognizing the complexity of the world. When I teach drawing I tell my students that vision (and thought) is a cumulative process. You can’t see a complex still-life set up in five minutes, you only see a glimpse of it. I use the example of a STOP sign. You only see as much of STOP sign as you need to know to stop. If you stare at it long enough you see the pattern in the reflective plastic or metal from which it’s made, you notice if it’s faded or if there’s a chip in the “S.” Then some asshole behind you in an Audi lays on their horn.

CR: Have you ever met a good artist who was dismissive of drawing? And would any artist who really doesn’t draw care to admit it?

MB: No good artist is dismissive of drawing. It would be like a good musician who dismisses notes. But I’ve encountered plenty of people who expand the definition of what it is to be an artist to the point where the activity of art-making becomes a category with no definition.

I’ve met artists who can draw claim that they can’t, but they’re not dismissive. It’s more of a humble-pie kind of thing. There’s a funny kind of guilt with some artists in which they feel as if they’re not allowed to just crank out a beautiful drawing — they have to subvert it somehow. And that’s fine. If they can subvert the tradition while showing me that they have control over that tradition, I think that’s the part of the bone where the good meat is. That’s radical. There’s an irony in a kind of de-skilled avant-garde point of view that is intended to be radical but in practice becomes a sort of Protestant iconoclasm that forbids skill or talent. But more and more I try not to gnash my teeth about it and just ignore the kind of art ideology that gives me indigestion. From my point of view I see attitudes toward skill in general and drawing in particular shifting. You can only serve people soup and call it art for so long. People always get hungry again.

CR: To some degree what you’re putting out here is similar to the attitudes about painting. Obviously drawing and painting are very different, and plenty of people who can and do draw never tackle painting. But when you mention the “de-skilled avant-garde,” which cycles in and out, you could be talking about trends (or “trends”) in painting. “People always get hungry again.” For what, exactly? Content, narrative, figuration, recognizable humanity? If so, how does drawing serve that?

MB: I’m not really convinced (although you might be able to convince me) that “de-skilling” in painting or drawing or sculpture or most any form of art cycles in and out. I think it’s been a pretty solid standard for my lifetime. The teachers in my drawing and painting classes when I was earning my undergraduate degree (with one exception), never taught me any technique. Things like how much linseed oil or water to add to paint, or how to break an image or an object down into its basic shapes when looking at it, or how to achieve this or that texture in drawing were pretty much completely ignored. I guess this was considered “academic” which is code for conservative. It was only in a watercolor class that I was taught some technique. I had to extrapolate from that class into acrylic and then oil. I think this has been the standard in art education since at least the ’70s.

When Kerry James Marshall was at Otis he raised a stink because he watched the conscious, ideologically-minded de-skilling take place as a matter of policy, right before his eyes. He was so pissed he chose not to go to graduate school after he left Otis.

Drawing is slightly different. People tend to exhibit a more natural ability; painting is more mediated. But even in drawing, putting some basic techniques and principles about how to approach a drawing — even an abstract drawing — can save a student years of fumbling in the dark. It’s also true that some people just can’t draw or paint. The world needs lawyers too, I guess.

All of the early 20th-century avant-garde garde from Kandinsky down to Duchamp and Picasso could actually draw and paint from reality. I agree with Robert Hughes that artists have to earn the “…right to radical distortion within a continuous tradition… .” You earn this right by learning to draw.

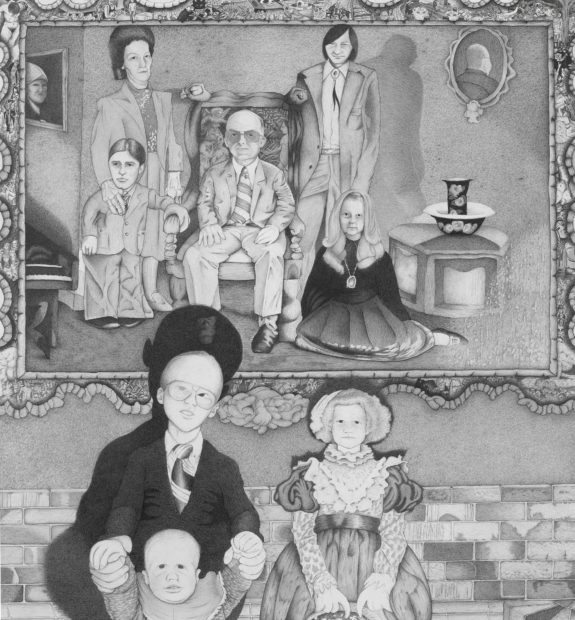

I’m not saying everyone should turn into Odd Nerdrum. My work is hardly academic, although I think plenty of people would say it is. I often use projectors and always deal with distortion, though I have eliminated the computer. But I seriously grapple with formal problems. Do I have a range of value that draws the eye? Am I using mark-making in a way that does service to the incredible variety of texture in the world? Does my drawing sit, however politically correct it may or may not be, like an old gray turd on the wall? The same goes for painting. And sculpture. And film and photography.

For me, content, narrative and subject matter are important, but less important than formal chops. They’re not even really separable. Technique informs content and vice versa. They feed off each other. But I can’t even become interested in any those things if the object is boring. And again, I think drawing, at least in the visual arts, is where it all begins.

The food metaphor is funny because I recently read an article about the decline in French cuisine in the US and it’s usurpation by Italian and Chinese cuisine. The author laid out the case that cuisine goes through cycles in which it gets complicated and overly elaborate and finally ends up kind of gross and silly. Then simplicity and honest ingredients are rediscovered. Overcooking, or undercooking, as in the case of most drawing and painting, is a lot harder to get away with if you’re not drenching the plate in a thick gooey sauce of elaborate political theory.

CR: For me one of the real seductions of drawing (of looking at it) is its immediacy and its intimacy. I suppose since most of us have at one point put a pen or pencil or charcoal or crayon to paper, we know how it feels to do it. It’s in our body memory, even if we don’t continue to draw throughout our lives. This gives drawing — even more specifically than the overall category of works on paper — a sense of, for the viewer, a more direct contact with the artist, his intentions, his process. When it’s a drawing made fairly public, it’s like a close communion between artist and viewers, and when it’s less public, it feels like a secret. Like a journal entry you’re privy to. Some of the drawings in the New Mexico show were almost certainly never meant to be made public, and there was something almost transgressive about seeing actual pages from Rembrandt’s sketch pad, where he’s working out the studies for compositions and faces. I can’t think of another art form like that, though the closest other thing we have in terms of intimacy and communication in all of those senses would be writing. You write and draw.

MB: I’m not a big fan of blurring boundaries — that thing where a painter says his painting is really a film or an installation artist tries to convince you that they’re a painter — but the drawing I do is based entirely on painting. I’ve tried to elevate drawing to the historical status of painting. In that sense my drawing takes on the ostentatious quality of painting with a capital “P.” Drawing with a capital “D.” This isn’t necessarily a good thing.

I don’t make sketches or preliminary drawings. My work eschews the kind of intimacy you see in a Rembrandt sketch, but what you see in one of my finished drawing happens in real time. I don’t plan much. I draw myself into and out of corners. Sometimes I don’t get out of the corner. My subject matter is always autobiographical. In that sense the directness of the medium and the directness of the subject matter are connected.

The unmediated quality of drawing that I mentioned before and that you just referenced is important to me. There’s a fairly direct line from thought to mark. I can and have painted but I haven’t felt like picking up a brush for the last 12 years. There’s a utopian idea that everyone can draw “in their own way” and it comes from the fact, as you said, that everyone doodles and scribbles. Not everyone paints. I think the universality of drawing is why it serves as the gateway to making art. Cynical as I am, I think I’m attached to this idea more than I sometimes care to admit.

I draw better than I write. And that gets me into trouble. I never lie when I draw but sometimes I lie when I write. I’m less fluent in writing than drawing and sometimes I say things I don’t mean. Or say things I mean in the wrong way. The folder on my desktop where I save my columns is titled “Writing for Money.” I’m not sure I’d write if I didn’t get paid. I’ll be drawing on my deathbed.

9 comments

I enjoyed this conversation about drawing. As an artist(painter), I reintroduced myself to drawing after years of making paintings. For almost two years now I draw 1 or 2 drawings daily; its hard for me too imagine doing otherwise.

I appreciated this dialog format! Keep ’em coming.

I have to disagree that drawing is an essential gateway to being an artist. It is an important one, and probably the most common, but there are approaches to making art that do not necessitate drawing or the visual sophistication an understanding of drawing imparts on the artist. Yes, the early to mid-20th c artists knew how to draw naturalistically before radicalizing the image, but that’s a product of art education then. I don’t see evidence that is necessary today (again, not that it’s helpful and welcome, but that it’s necessary). In today’s art world, I would agree it’s a bonus to be able to draw in that it helps communicate your ideas to yourself and others, but one can look at many successful artists where drawing is immaterial to their work. I think working artists as ourselves tend towards views that the means is important, but to the viewer, it really is the ends.

Comparing drawings to notes of music, as a fundamental element irremovable from the art form, is inaccurate. With current technology young (and older) artists have numerous avenues to approach the physical arts (not even getting into relational esthetics, which I did enjoy your dig at) that simply don’t require drawing.

Are the fundamentals of art still necessary? Yes, mostly. Perhaps you are conflating the knowledge of drawing with the knowledge of line? One can teach people the fundamentals without lifting a pencil (or scissors, or glue). And I agree we can often, but not always, see in sculpture, multi-media, etc whether the artist has a grasp of fundamentals. I don’t buy that this extends to drawing, not that it should.

In summary, I am not denigrating drawing and its rightful place of *equality* with all other media, but don’t agree with your dismissiveness of artists who do not put a primacy on the ability to render nature as the sole door through which one must pass to being an artist today.

As many know, I come from the old art school of thought, that drawing is essential as part of the curriculum. In my opinion, it’s a bit sad that art students with zero real life drawing experience, or painting from real subjects, as an exercise in seeing, and “translating” what you see with your hands (or whatever limbs) into something visually pleasing; showing skill in composition, can actually get a BFA, or even an MFA. You don’t need actually “artistic talent” anymore to be an artist. One can simply arrange found objects in odd ways, have some banners printed with clever ironic phrases, throw some junk together in a gallery corner, or on a table, any sort of rehashed old and tired Duchampian or Fluxus influenced work. Don’t get me wrong, some of that stuff I think is a bit funny (for a few seconds), and works well as an ironic visual statement or protest that may be strange to see in a gallery. But if you are a young art student or grad student that cannot draw worth a shit, and expect to become a famous artist, or at least make a living with your conceptual art? I would say “keep your day job.” Now, “get off my lawn ya goddamn brats!” 😉 Yours lovingly, KP

It has always been relevant ad it always wil be. I’ve waited for a long time to here what you said in your article here in the USA. Thank you.

I have always had a difficult time figuring out what is and is not a drawing and, therefore, whether an artist is drawing or not. It seems that some people have a notion that “effective” drawing is critical to successful art making. I searched around a bit on the internet and did discover that “drawing” (whatever it might mean) is not a universal concept or category. Perhaps someone can help me with a few questions: what is drawing (the activity) or a drawing (the end produce)? And when (and where) did “drawing” become a category in art discourse? Thanks for your help!

I have to agree with Bise on everything. Comparing drawing to notes of music is a fabulous comparison. The connection between those two disciplines are about the fundamentals . There is a pattern to this life, learn the fundamentals and you can further your advancement in ANYTHING you do. Art is not immune to this concept.

Drawing is not so much about the hand, but learning how to see. Many students don’t know how to gaze upon an object. Seeing takes practice and once the student knows what to look for, then the drawing will develop in quality. Perception is a learned experience, which makes a better drawing and aids the artist in the development of their ideas. And in a way, makes one more sensitive in their own approach to their work, whatever that might be. Despite the advancement of computers and multi-media, if an artist has poor drawing skills, nothing can really mask that deficiency. Usually the work will come out weak, compositionally compromised and will generally come out looking half baked. Drawing helps the artist develop their eye in the most sensitive of ways and it that spills over in their perception of the world.

When I was teaching at North Texas I came across other grad students who were teacher assistants, who thought that drawing was an outmoded concept. So they wouldn’t teach their students in the traditional way. I thought they were cheating their students of having the experience of developing their eye. Too bad. I will always side on the artist that makes the effort to explore drawing than the one who dodges the exercise. Nothing is gained by omitting the experience of drawing, but everything can be made possible by its practice.

Art is no different than any other experience. The more you know about drawing, the better off you’ll be in the pursuit of your ideas. Learning the fundamentals of drawing provides the artist with a finer scope of perception. A sensitivity is developed building the power of perception and thusly, providing a foundation for the imagination.

Michael more eloquently wrote what I was trying to get across. A young artist in school, should sharpen their skills with fundamentals like drawing. It truly does develop one’s ability to see objects, forms in three-dimension, movement even, in new ways. It is a practice that is simply an enhancement to any artist’s skill set.

Enjoyed this, thanks!

I was taught that drawing is the fundamental step to being an artist. In the 70’s I spent a year going to an art school learning how to draw before starting in University on my art degree ( in Germany). I agree with Michael and Christina, something happens between the eye, the brain and the hand, an automatic training thats facilitates ways of seeing and produces an intelligent line.

Great topic, now to dust off my sketch book.