Like many artists in this country, I’ve been thinking about racism in America more and more since the demonstrations in Ferguson, Missouri a year and a half ago.

My early lessons in racism came from watching old westerns on VHS and living in Flagstaff, Arizona. Coconino County has almost 7,200 square miles of designated Indian reservation including the Navajo, Hualapai, Hopi, Havasupai and Kaibab, but it doesn’t have a lot of black people. The brown kids in my junior high school had long hair, wore Slayer t-shirts and everyone called them Indians.

Childhood experiences of racism in semi-rural Arizona depend on which side of the barbed wire you’re born. Being human is complicated, but racism is simple. Between the Indian reservations and the Border Patrol, that blunt distinction remains especially clear in my home state. But for every kid on either side of any racist divide there comes a time when they figure out that in this country, they’re either a cowboy or an Indian.

Even when, as I did, you figure out that you’re mostly out of range of the gun tower and the breadline because of your checkbook and your skin color, the realization is still a bitter one. Kids don’t care what color people are until they’re told to care. The human species isn’t subdivided by race. Sew a kidney from a white guy into a black guy and the piss still comes out yellow. It works across sex too, but as every good comedian knows, the difference between men and women is a whole different act.

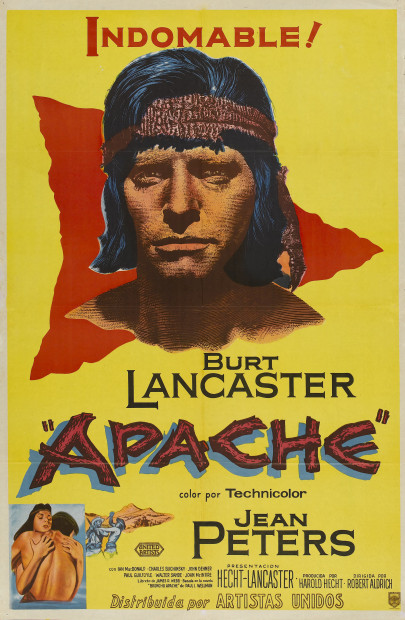

I was a sheltered kid in a Christian cult with no television. I learned who I was by watching old movies at my grandma’s house. By the time I was eight or ten, I knew that white guys played the Indian warriors in westerns. I saw the same actors in other movies without the wigs and makeup. This just seemed stupid. It was always obvious to me that Burt Lancaster couldn’t be Wyatt Earp and Massai the rebellious Apache warrior.

It always took me out of the story. It was dishonest and made for bad art. It seemed obvious to me that people who looked like the Native American kids I rode the bus to school with should be playing these roles. That small act of unconscious art criticism was, for me, the first win against the constant and continuing diet of racist, classist propaganda that Hitler and Goebbels credited American advertisers with pioneering.

When I moved to the Dallas suburbs in ’89 the heavy metal Native American kids disappeared mid-semester and I was in high school with African American kids listening to hip-hop. I had never seen so many black people in one place as I did in DeSoto High School. Before I came to Texas I didn’t realize what a thin slice of the world I experienced without a TV in the Arizona mountains. For the first year I thought everyone was calling each other “doll” instead of “dawg.”

A 4H guy named Shane, who had a mullet, wore brutally tight Wranglers and called girl’s hips “saddlebags,” clarified the issue and let me borrow his cassette recording of The Fat Boys Are Back. It was the first hip-hop record I ever listened to. Two years later Rodney King got his police beating and I slowly began to understand that the Apaches weren’t the only ones who got shot by cowboys and that, as Antonio says in the Tempest, past is prologue.

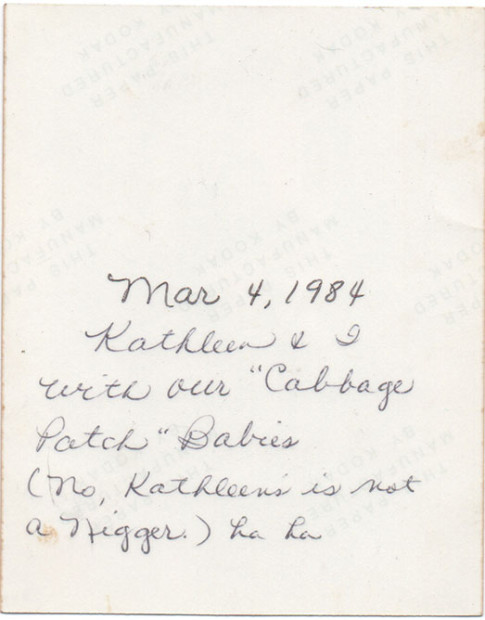

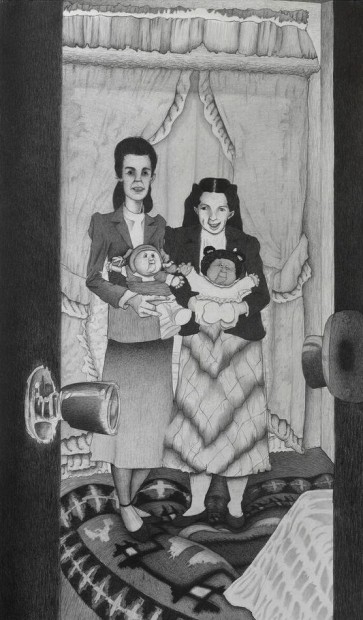

Many of the loose, disconnected narrative strands surrounding my experiences with racism as a white man in America found themselves neatly tied together recently in an inscription written in careful cursive on the back of a family photograph I found in a box of snapshots a year or so before Darren Wilson fired his gun twelve times and killed Michael Brown in Missouri.

The photograph depicts two women who were members of the church I grew up in. They’re each holding a Cabbage Patch doll from that era in the early 80’s when America apparently experienced mass hysteria and started “adopting” inanimate objects. The older woman holds a white doll and the young girl, her teenage daughter, holds a black one. I turned the photo over and read the following inscription:

I can’t say it surprised me. But it was the first time that the word really took on its original force and meaning for me. Like everyone else in my generation black, brown and white, I’ve sung along to The Chronic and watched Friday a thousand times. But seeing the word written—the “n” that begins the “n-word” and the double g’s one right after the other like two gunshots—in the soft handwriting of a woman I remembered was surprisingly shocking. As I slipped the photo into my pocket to take back to my studio, I thought: “Poor Kathleen.”

1 comment

I am Indian, 100%, from South Asia and am concerned about the misnomer that the word Indian is used to describe Native American tribes for generations. As an artist growing up in Texas, it was difficult. My teachers had asked me what tribe I was after I told them I was Indian. We don’t have any tribes, then they proceeded to ask if any of my relatives lived on a reservation. Very confusing to a young boy. For many years, I wrote drafted letters to the federal government asking them for my tax-free gambling land as it was understood that if you were a percent Indian as I was 100%–both parents and grandparents Indian, born in India, I was to attain this land. I never mailed the letters, just collected them as works of art and irony.

The world in 2016 understands that Columbus was wrong, he did not end up in India, though he did end up calling the natives he encountered, as Indians. I guess he didn’t want to be marooned by his shipmates after a long journey of not finding land. Years later, I joke, that in fact, my people are still waiting for ‘Chris’ to find them back home in India.