Franz X. Winterhalter, Portrait of Napoleon III, 1852

In High Society, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston presents the 19th-century German court painter Franz X. Winterhalter’s beautiful, ice-cold portraits of the European aristocracy, staging their gorgeous last stand against the collapse of the feudal order that had ruled Europe for 800 years. After the Revolution of 1789 Napoleon I began exporting liberté, égalité, fraternité at the end of a bayonette across all of Europe. When, in 1814, a truly great Spanish court painter named Goya painted an incident from Spain’s resistance to the Napoleonic Wars that occurred on The Third of May, 1808, Winterhalter was nine years old and probably working on his father’s farm and resin-making business in the Black Forest.

Given that it has become harder and harder to not see traces of neo-feudalism cropping up in contemporary life with its demands on privacy and freedom of speech in the name of protection, combined with high and narrow concentrations of wealth, this exhibition is timely. As I walked through the large collection of idealized but psychologically sharp portraits of many of the major players on the conservative side of the first Modern culture wars I asked myself very seriously if Franz X. Winterhalter might not present a more relevant prism through which to examine our contemporary social moment than would Paul Cezanne or Edouard Manet.

Franz X. Winterhalter, Madame Rimsky-Korsakov, 1864

Certainly the hyperreal clarity of Winterhalter’s pictures and his indulgence in opulence have more in common with the images we see on the screens of our computers and televisions than do Renoir’s well-fed pink bathers. 19th-century painters like Courbet, understood as radical, appropriated photography in order to resist it, to give painting meaning beyond its ability to represent the visual world. Photography’s ability to affix an image of visual reality to paper blew the lid off the camera obscura and exposed the court painter’s greatest secret, giving it away to every person on the planet. In the face of this radically socialist yet market-driven revolution in image-making the artists we consider reactionary dealt with photography not by evading it but by doubling down and attempting to outdo it. But like their patrons, they had already lost the historical game. The next century would be one defined by new fortunes, new lineages and new forms of art.

Franz X. Winterhalter, Portrait of Leonilla, Princess of Sayn Wittgenstein, 1843

Winterhalter’s painting style is politically reactionary. But rather than understanding his work as reactionary in the loose contemporary sense of the word in which we imagine a reactionary as a bigoted idiot who just couldn’t see the coming coal-burning train of Modernism for the all the smoke, we would do better to understand it as consciously, even proudly conservative. Winterhalter, like the more famous (and more interesting) Ingres, of whom he is a pretty good follower, understood the dissolution of traditional standards in painting and society and rejected it. The difference between a reactionary and a revolutionary lies in fundamentally different perspectives on the nature and possibility of human progress.

The reactionary perspective is one in which most people always remain poor and powerless while elite factions of opposing powers seek control through convenient ideologies. And seen from this angle, revolutionaries are clever usurpers interested not in equality and human rights but in taking power for themselves. This view of man as a social creature intent only on the acquisition of power seemed true to many on both sides of the battle against monarchical power when Napoleon I declared himself emperor and restored the monarchy and the Catholic Church just six years after Marie Antoinette’s pretty head met the 45-degree angle of a guillotine blade. The revolutions in France replaced the severed heads of one royal class with the heads of another.

The court painter might be the least naïve kind of artist. Whatever class he may have emerged from, his deep view into the hallways of wealth and power allows for a long, often cynical historical perspective. Through this lens, courts and ideologies change but the game of power and control remains the same. Winterhalter was a court painter to many of the weakened European monarchies that, after WWI, finally become the empty symbols we see them as today. But now, a hundred years on, his images of privilege and ostentatious wealth in the face of volatile class conflict once again seem familiar and relevant.

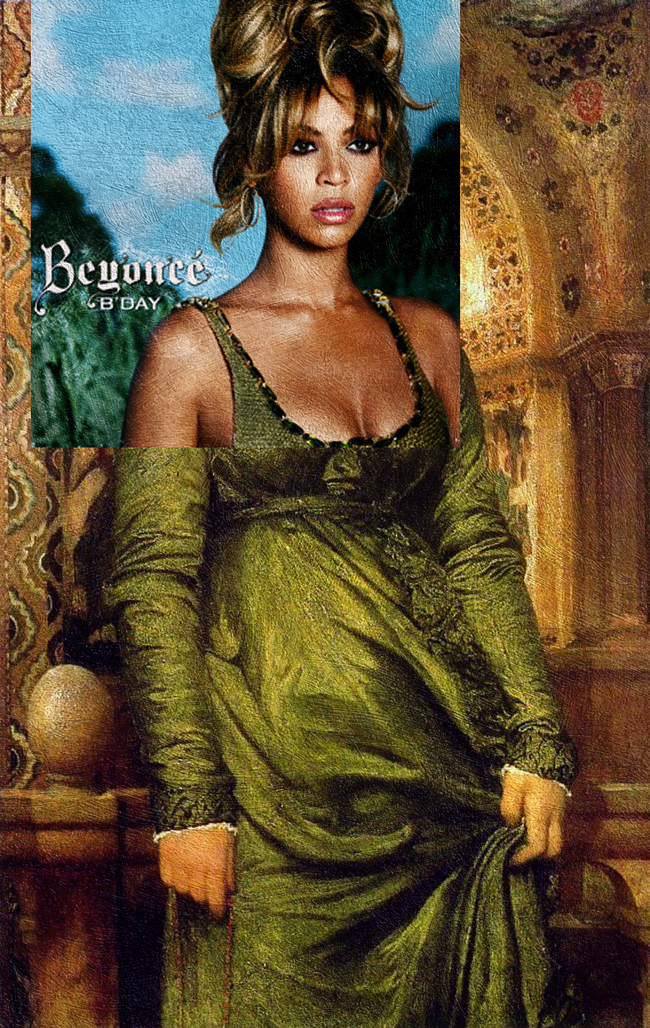

Kehinde Wiley, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 2005

In the last two or three decades, the dust bunnies of a hundred years of storage in basement museum stacks have been brushed away from the Neoclassical style of the 18th and 19th centuries. Artists like Catherine Opie, Lisa Yuskavage and Kehinde Wiley, to name only a few, have made post-colonial cultural claims about the democratic franchise by using the visual language of Old Europe. Are these ironic criticisms of power itself? Or are they more straightforward than that? Are they in fact not criticisms of power but claims to it?

Catherine Opie, Self Portrait/Nursing, 2004

Lisa Yuskavage, Transference Blot Portrait of My Shrink in Her Starched Nightgown with My Face and Her Hair, 1995

The answers we might give and our feelings about the question itself reveal much about our inclinations toward progressivism or conservatism. There is a broad social promise implicit in the idea that the racial, sexual or cultural backgrounds of those in power change the nature of power. But is this true? Or is it the same quest for the same power and glory under a different cultural flag? I think Winterhalter would look at the question with cool detachment and prepare whatever pigments he might need to accommodate the colors of the next regime.