There is a reason that Yayoi Kusama’s mirrored infinity rooms with little blinky lights are wildly popular, with lines around the block and cash registers a-whirring wherever they are shown. The 87-year-old Japanese artist’s darkened spaces subsume a viewer—only one, only you—into a glittering, infinite horizon that evokes pleasing narratives: is this some kind of endless, ambient, groovy disco? Is it perhaps a collection of souls, a vision of heaven? Like the Japanese funeral lantern ceremonies that inspire them, Kusama’s rooms speak to the soul that wishes to be a part of something greater than itself. No one can get enough of infinity when it’s this pretty.

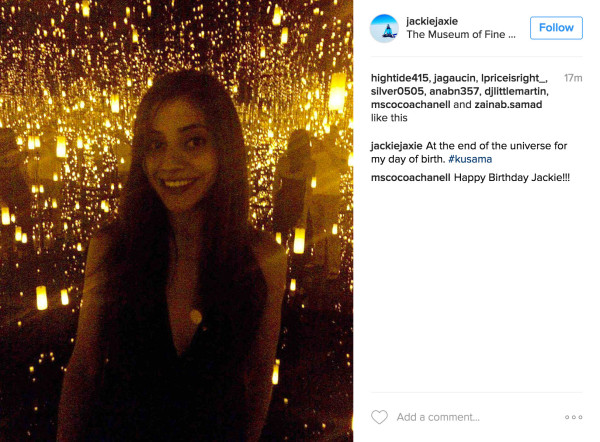

What is most interesting about the success of Kusama’s infinity rooms, specifically Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity, which the Museum of Fine Arts Houston recently acquired, is that it looks far better on a cell phone than it does in person. The virtual experience of Kusama’s room is better than the actual.

In person, the sickly orange, energy-efficient LEDs in the room are nothing like their lemony counterparts that have littered Instagram since the show opened in early June. Also in person, the sense that one is standing in a small mirrored room is far more palpable — the seams between the mirrors more visible, the corners more obvious. Visitors to the Kusama wait in lines that sometimes stretch outside the museum itself and down the sidewalk. The crowd’s reward is a tightly controlled 45 seconds inside a room, the actual experience of which can never be communicated except through a medium that makes it look better, cooler, more infinite, more eternal.

It’s not a coincidence that this is all reminiscent of people waiting in lines to pay respects at the coffin of a beloved head of state; or the lines to sacred sites like St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome; or the lines to experience a two-minute ride at Disneyland. The frenzied popularity of Kusama, for years now a megawatt international art celebrity, brings to mind Robert Hughes’ musings on the 1963 visit of the Mona Lisa to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “They didn’t come to look at the Mona Lisa. They came in order to have seen it. And there is a crucial distinction, since one is reality and experience and the other one is simply phantom. In America the Mona Lisa turned into its own facsimile.”

When you finally make it into the Kusama room, you had better have your camera ready, because that’s the prize: the proof that you saw it, more valuable than the seeing itself. At the time of the Mona Lisa visit, Andy Warhol said someone should just make a copy of da Vinci’s masterpiece and send that, since nobody would know the difference. Kusama’s mirrored rooms are easily copied, and sent globally, thanks to technology. What’s more, the copies are better than the original. Andy would probably enjoy that.

What this says about our culture and our species goes far beyond the usual fretting around art-as-spectacle and museums-as-theme-parks. (Tickets for your 45 seconds in the MFAH are $18 for non-members; $25 if you want a so-called Fast Pass.)

If you think back through millennia of grand religious pageantries and buildings, human beings have always loved a good show when it comes to seeing God. And I think God is exactly what Kusama is getting at in these works: her titles evoke infinity and eternity, both acceptable substitutions for the word “God” in our secular age. We are drawn to Kusama’s flickering lights very literally like moths to flame.

It’s worth considering what a departure all this is from Walden. If we want to perceive infinity, these days we immerse ourselves in phony sensorial “experiential” art. Weren’t we once able to see God in simpler (to say nothing of far cheaper) ways? Whatever happened to nature? Whatever happened to the divine in the everyday? Remember Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven’s 1917 readymade sculpture of a drain pipe that was simply titled “God”? Imagine having lines around the block and expensive tickets to see that piece.

But maybe Thoreau and the batty Baroness Elsa are the outliers. Maybe such simplistic, observational approaches to ideas around human spirituality have never really satisfied, at least not in the West. Maybe Kusama’s rooms are just the latest in a grand lineage of expensive, sensational, immersive art experiences about God — only this time, the museum is the one passing the collection plate.

This is the first in a series on immersion art. Part two, on Meow Wolf in Santa Fe, is here.

10 comments

Don Delillo knew the score:

Soon the signs started appearing. THE MOST PHOTOGRAPHED BARN IN AMERICA. We counted five signs before we reached the site. There were forty cars and a tour bus in the makeshift lot. We walked along a cowpath to the elevated spot set aside for viewing and photographing. All the people had cameras; some had tripods, telephoto lenses, filter kits. A man in a booth sold postcards and slides–pictures of the barn taken from the elevated spot. We stood near a grove of trees and watched the photographers. Murray maintained a prolonged silence, occasionally scrawling some noes in a little book.

“No one sees the barn,” he said finally.

A long silence followed.

“Once you’ve seen the signs about the barn, it becomes impossible to see the barn.”

He fell silent once more. People with cameras left the elevated side, replaced at once by others.

“We’re not here to capture an image, we’re here to maintain one. Every photograph reinforces the aura. Can you feel it, Jack? An accumulation of nameless energies.”

There was an extended silence. The man in the booth sold postcards and slides.

“Being here is a kind of spiritual surrender. We see only what the others see. The thousands who were in the past, those who will come in the future. We’ve agreed to be a part of a collective perception. This literally colors our vision. A religious experience in a way, like all tourism.”

Another silence ensued.

“They are taking pictures of taking pictures,” he said.

He did not speak for a while. We listened to the incessant clicking of shutter release buttons, the rustling crank of levers the advanced the film.

“What was the barn like before it was photographed?” he said. “What did it look like, how was it different from other barns, how was it similar to other barns? We can’t answer these questions because we’ve read the signs, seen the people snapping the pictures. We can’t get outside the aura. We’re part of the aura. We’re here, we’re now.”

He seemed immensely pleased by this.

so great

Unfortunately the book feels monotonous and pretentious, in my opinion. But, with this quote it certainly makes me appreciate the words a bit more – they do apply well to the absurdity of some observable things. But damned if reading that book is a chore, when it goes well beyond the point of thinking “yes I get it now, please move on…” when reading. Nice excerpt though, definitely comparable.

Also on topic, let’s not forget that Yayoi wasn’t the first:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AFc1BeS0vKI&feature=youtu.be&t=40m25s

In her autobiography, Kusama claims Samaras took her idea. On another note, have a under a minute to experience infinity seems pretty ironic.

That wouldn’t surprise me, although neither of them were exactly first to the idea.

http://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover-estate/the-palace/the-palace/the-hall-of-mirrors

Rainey, I love that you’ve quoted Robert Hughes from his great documentary, “Mona Lisa Curse.” A very relevant reference indeed. I wish the MFAH would screen that film.

Agree with your review 100%. Once we went through I was completely underwhelmed. My friend asked me ‘is that it?’. It was only when I got home and went through the photos did I see what that piece was. The experience is only a minor part. The capture of the experience is everything. And it was good being in it with strangers as all kinds of fun things happen. Going back next weekend.

Do I spy a reference to Jump Little Children’s song – Cathedrals ? I almost had that song played at the Rothko Chapel for my wedding… but I thought it almost too on the nose.

No, I didn’t know that song. I like it though. People have been pointing out for a while that museums are the new churches, both in good ways and bad.