Ernesto Neto, SunForceOceanLife, 2020, mixed media installation, view of visitors ascending spiral from the left; the green section on the right is the exit, 30 feet x 79 feet x 55 feet, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo source: MFAH.

Ernesto Neto, the Brazilian artist whose work straddles multiple categories, including installation, fiber, and conceptual art, has created a monumental, multi-sensory crochet artwork for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH). This site-specific piece, created for the Cullinan Hall of the Caroline Wiess Law Building as part of MFAH’s annual summer immersive series, is the first work by Neto to join the museum’s permanent collection. Suspended nearly 12 feet off the ground, the giant spiral-shaped work measures nearly 30 feet x 79 feet x 55 feet.

Visitors ascend into the spiral near the entrance to the pavilion and wind their way to its center by one of three paths; three other paths, in turn, lead from the center to the exit on the other side of the spiral, near the south wall.

Ernesto Neto, schematic rendering of SunForceOceanLife, 2020. Photo source: photograph from video titled SunForceOceanLife, 2021, director Marcos Oliveira, running time 8 min. 5 seconds.

The work is so large that its structure can only be fully pictured in a schematic rendering. Even after one has passed through it, its precise forms remain mysterious and difficult to reconstruct in the mind’s eye.

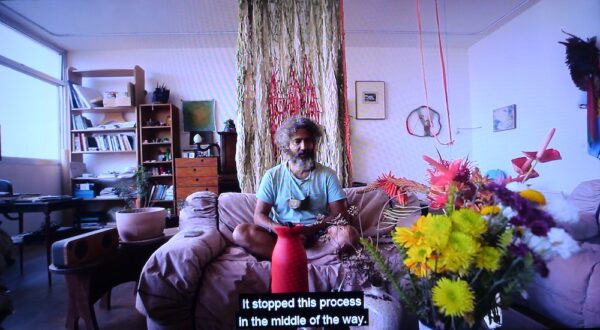

Ernesto Neto discussing SunForceOceanLife. Photo source: photograph from video titled SunForceOceanLife, 2021, director Marcos Oliveira, running time 8 min. 5 seconds.

According to the artist, SunForceOceanLife is a commentary on the cyclical relationship between the sun and the sea that produces life. Above all, it “is about fire, the vital energy that enables life on this planet,” says Neto.

Ernesto Neto, SunForceOceanLife, 2020, mixed media installation, view of entrance to the pavilion; entrance is on the left, exit on the right (both are slightly elevated from ground level), 30 feet x 79 feet x 55 feet, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo source: MFAH.

Neto was born in 1964 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where he currently works. He studied at Rio’s Escola de Artes Visuais do Parque Lage (1994-1997). The commission for the MFAH work was finalized in 2019, and it was fabricated during the Covid-19 pandemic. In a short video by Marcos Oliveira that plays continuously near the installation at the museum, Neto explains that instead of creating the monumental work at a large workshop, he had his team fashion the individual components at their respective homes in order to avoid exposure to infection.

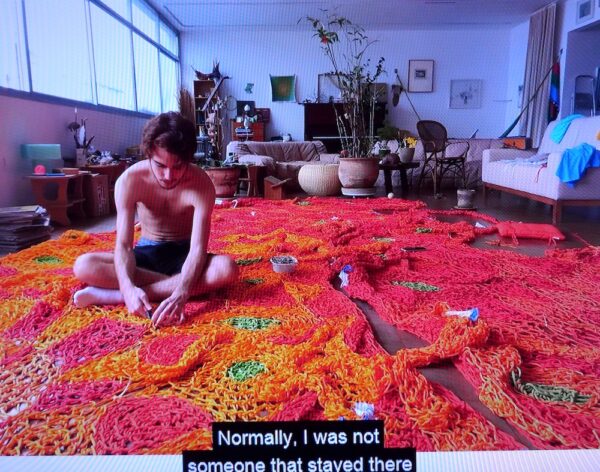

Assistant working on SunForceOceanLife in Rio de Janeiro. Photo source: photograph from video titled SunForceOceanLife, 2021, director Marcos Oliveira, running time 8 min. 5 seconds.

The “cells” that form the floor on which visitors walk were stuffed with plastic ball-pits balls in Houston by a large crew, which included volunteers. The entire ensemble was suspended from the ceiling of Cullinan Hall.

Neto’s art draws on multiple aspects of Brazilian life, and individual stages of work on his projects include ceremonial observations. Upon the completion of each section of the spiral, the artist and his assistants burned both ends of the polymer string “in a gesture that evokes meditation, prayer, and other sacred rituals.” Neto adds that he hopes that the experience of passing through this work will be “like a chant made in gratitude to the gigantic ball of fire we call the sun,” and in effect “a gesture of thanks for the energy, truth, and power that it shares with us as it touches our land, our oceans, and our life.”

Ernesto Neto, SunForceOceanLife, 2020, mixed media installation, oblique view of entrance with people standing in line, 30 feet x 79 feet x 55 feet, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova.

The yellow, orange, and green colors are meant to evoke life arising from the sea through the energy and agency of the sun. As viewed from the exterior, the areas around the entrance and the exit are the greenest. These sections symbolize chlorophyll, the beginning of plant life. These green areas at the entrance and exit are at the farthest remove from the fiery, red-orange core of the sun.

Ernesto Neto, SunForceOceanLife, 2020, mixed media installation, oblique view of entrance with people standing in line on the left, and the exit on the right, 30 feet x 79 feet x 55 feet, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova.

Mari Carmen Ramírez, Wortham Curator of Latin American Art and Founding Director of the International Center for the Arts of the Americas (ICAA) at the MFAH, explains how Neto has transformed crochet, “a popular Brazilian craft, taught to him by his grandmother and typically executed by women on a small, delicate scale,” into highly symbolic “massive structures that float several feet above the ground.”

Ernesto Neto, SunForceOceanLife, 2020, mixed media installation, view of visitor grasping the sides as s/he treads on a “cell,” which is essentially a crocheted tube jam-packed with plastic balls, 30 feet x 79 feet x 55 feet, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo source: MFAH.

Fibers consisting of 18 custom colors are blended into each cord, except for the center, which is solid green. The cords are hand-woven into patterns that recall forms such as spider webs, fishing nets, suspension bridges, and hammocks. All of these seemingly individual sections and components are interwoven, and combine to create the giant spiral.

Each pathway recalls a primitive suspension bridge, such as those featured in movies, which hangs from vines or ropes. But instead of a solid — if somewhat mobile — floor, such as that offered by a wooden plank walkway, each individually knitted section (which the artist refers to as a “cell”) is like a tightly packed mesh bag or net. Each cell is stuffed full of plastic balls. Imagine, if you will, a mesh bag such as one used for baby potatoes at the grocery store, but filled so full that the mesh is tightly stretched in every direction. Then imagine a pathway constructed out of overfilled mesh bags that are joined together.

Before I experienced SunForceOceanLife, I imagined that the plastic balls would be softer and more pliable than they are in the flesh — and on the flesh. I imagined that it would be like walking on a tightly packed net filled with slippery, flapping fishes. But the individual balls don’t compress very much, nor are they slippery. Nor do they seem to move the way I expected them to move. Instead, your feet sink into the cell, and the entire cell moves and swings. This in turn, causes the surrounding sections to move and sway. To use the terms applied to Calder sculptures, it resembles a stabile when you look at it from a distance, but it feels much more like a mobile when you are on it.

The energy caused by my weight and motions seem to be absorbed more by the crocheted fibers than the balls. One’s feet sink into the cell, because there is nothing solid beneath the balls. This causes the cell to rock with the stress. Imagine walking on a suspension bridge buried in quicksand, one that requires you to walk with your hands as much as with your feet. Your feet seem unable to carry the load, because the only certain “footing” is with your hands. Every time you lift one foot to take a step, your other foot sinks even deeper into the cell.

You have to pull your way across because walking does not suffice. Pulling does not suffice either. I felt like I was half-swimming through some entirely foreign element, which is why I used the analogy of quicksand. No two steps are ever alike. The path you are crossing on is affected by your own transit. It also responds to everyone else who was recently on the spiral. Even if someone is stationary, they affect the balance and the motions of the entire suspended form. Everything and everyone is connected.

Ernesto Neto, SunForceOceanLife, 2020, mixed media installation, entrance to the spiral, 30 feet x 79 feet x 55 feet, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova.

In turn, when one enters or exits the spiral, the cell that forms the tip is pushed to the ground, and this has a ripple effect, not unlike a wave on a body of water. The oceanic effect that I experienced on SunForceOceanLife was that of rhythmic movement and connectedness.

Intellectually, I know that my feet — rather than my hands — carried most of my weight. But I felt like I could not trust them anymore, because I could not take a single step without simultaneously grasping the fibers on either side of me with both hands. Each step was like climbing a soft, swaying staircase that changed with every step. You feel like you are climbing, even when you are walking downhill. I had to pull with my hands before taking every step, and that affected the cell on which I stood, as well as the cell onto which I was ascending or descending. One senses that the pulling and stepping motions also affect the entire piece.

I never had an experience like this before. I had read the press release and I had looked at pictures before my visit. I imagined carefully looking where I stepped and carefully calibrating my balance, equilibrium, and motions. I couldn’t have been more wrong. Balance, equilibrium, and stasis do not exist on SunForceOceanLife.

One must attune one’s body to the rhythmic movements each visitor produces within the swaying spiral — and even to the vibrations left behind by their departure. This requires a different way of sensing. “For me, mind and body are one thing, always together,” says Neto. Instead of thinking, visitors must sense, step, grasp, and pull their way through the spiral, which seems like a giant, living organism. It seems to breathe and sway in response to individual touches, as well as to the collective burden imposed by the humans who tread on it.

Ernesto Neto, SunForceOceanLife, 2020, mixed media installation, view of two people, one ascending and one descending the spiral, 30 feet x 79 feet x 55 feet, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo source: MFAH.

According to Neto, SunForceOceanLife “unites the disciplines of art and culture with biology and cosmology” by directly engaging the body “as does a joyful dance or meditation.” It is thus an invitation “to relax, breathe, and uncouple our body from our conscious mind.” That invitation is in fact a necessity. You don’t think or reason your way in or out of this maze — you grasp it.

Ernesto Neto, SunForceOceanLife, 2020, mixed media installation, woman passing through a red-orange section near the center of the spiral, 30 feet x 79 feet x 55 feet, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo source: MFAH.

Neto sought to produce the “sensation of floating,” and that of being “cradled by the crocheted fruits of our labor.” Unlike a suspension bridge, there is no way to fall off. Touch is the first sense humans develop, before smell, taste, hearing, or sight. And touch — even more than sight — is what gets one through the spiral. Visitors must wear socks, but no shoes, so one feels plastic balls with every step. One still uses sight, but one doesn’t know what one sees. Intuition assumes primacy. All I knew for certain was that I had better not let go of the fibers with either hand when I was about to take a step. I knew this without having to think about it.

Neto compares the work to a hammock, which he calls “the quintessential indigenous invention that uplifts us and connects us to the wisdom and traditions of our ancestors.” Each path may sway like a hammock tethered to ancestral trees, but I don’t think visitors will feel like they are on a hammock unless they sit for an extended period, which can be done in the center of the spiral.

Ernesto Neto, SunForceOceanLife, 2020, mixed media installation, view from the path near the center of the spiral, 30 feet x 79 feet x 55 feet, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo source: MFAH.

This illustration shows the tubular, three-dimensional quality of the cells that constitute the pathway.

Ernesto Neto, SunForceOceanLife, 2020, mixed media installation, view of colored patterns in the netting from the center of the spiral, 30 feet x 79 feet x 55 feet, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo source: MFAH.

The experience that eventually led to this commission can be traced back to a trip to Buenos Aires in 2012, when Mari Carmen Ramírez and members of the museum’s Latin Maecenas experienced O Bicho SusPensa na PaisaGem. This was Neto’s first large-scale immersive environment, which was exhibited at the Faena Cultural Center. Universes Art Magazine has an online album of 12 images of this work.

Ernesto Neto, O Bicho SusPensa na PaisaGem, (Bug suspended in landscape), 2011, installation at the Faena Arts Center, Buenos Aires, colored ropes, crocheted fiber, plastic balls, stones. Photo source: Faena Arts Center.

Jessica Morgan, who curated O Bicho SusPensa na PaisaGem, wrote that Neto’s sculptural environments “both respond to and are inspired by sources as diverse as the uniform architecture and design of the rationalized world,” as well as the “organic culture and beach trade of his native Rio de Janeiro.” She added that he is “a shrewd observer of the attempts by capital to organize and systematize our environments, and in many ways, his work is a response to these limitations, one that tries to bring his viewers a fresh way of dealing with the world, a way less obsessed with efficiency.”

Neto thus invites us to “experience an environment beyond the usual cuboid that normally contains and constrains our bodies.” SunForceOceanLife is a particularly colorful and organically-shaped alternative to the white cube that houses it at the Museum of Fine Arts. One could argue that the spiral is the quintessential natural form, one that inhabits both microcosm and macrocosm, from DNA to fingerprints to flowers to shells to hurricanes to galaxies. The cuboid, on the other hand, can be viewed as the quintessential industrial man-made form, an unnatural, no-nonsense, practical, and cheap way of constructing spaces.

Morgan holds that Neto’s work “contains a radical approach to living, as well as the tools to examine our everyday surroundings.” She notes that daily life is bereft of “sensorial pleasure” and “undirected thought.” Moreover, “electronic communication with little or no real social contact or physical interaction” has increasingly replaced play, even for children. SunForceOceanLife is fun — it seems more like a fun-house ride or attraction than a conventional art installation or sculpture. But it is not purely and purposely ludic.

Morgan writes that Neto is concerned with the “negotiation of space, place, social relations and the role of the local in the global,” one deeply informed by Brazilian history, including its colonial past and U.S. political interference. She relates O Bicho SusPensa na PaisaGem to “the subjective understanding of what it means to be on the periphery and the conflict between western and non-western status.”

Ernesto Neto, SunForceOceanLife, 2020, mixed media installation, view of lower center; exit on the far right, 30 feet x 79 feet x 55 feet, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova.

Ramírez and the Latin Maecenas group that traveled to Buenos Aires in 2012 were so impressed by O Bicho SusPensa na PaisaGem that they invited Neto to speak at MFAH the following year. Ramírez and Gary Tinterow, the Museum’s Director, initiated conversations with Neto regarding a possible commission for an immersive environment in Cullinan Hall. This project, which was in the works for several years, was completed in 2020, but was not installed until 2021 due to the pandemic. It was worth the wait.

The massive scale of this venture is mind-boggling. SunForceOceanLife weighs 6,000 pounds and is fabricated out of nearly 309,000 feet (more than 58 miles) of string. The 360 feet of pathways are made up of cells filled with 117,000 plastic balls.

Ernesto Neto, SunForceOceanLife, 2020, mixed media installation, close up of two joined cells, 30 feet x 79 feet x 55 feet, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova.

Note how the cells are crocheted together and that the cords are woven out of differently colored fibers.

Ernesto Neto, SunForceOceanLife, 2020, mixed media installation, view of center from below, 30 feet x 79 feet x 55 feet, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova.

Most of the balls are orange, though some are purple or black, and these increase in frequency in proximity to the center. The dark balls represent “black spots,” which are caused by looking at the sun. The cords that make up the center are green, and they are filled with clear plastic balls.

Ernesto Neto, SunForceOceanLife, 2020, mixed media installation, view of center interior, 30 feet x 79 feet x 55 feet, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo source: Ruben C. Cordova.

The center of the interior held a real surprise for me. I had assumed that the color green was largely confined to the entrance and the exit. But a cord of green shoots right out of the green button in the orange-red center, like a giant sprout emanating from the middle of the sun.

After I exited the piece, I was told that some visitors reported that they heard sounds like ocean waves, created by people walking on the balls. I did not. I searched my memory. I was talking until I got on the spiral. Maybe I blocked off any sound during my ascent. By the time I was in the center, I was almost the only one on SunForceOceanLife. Were the other visitors making a tsunami out of a molehill of sound? Or was I just oblivious?

Later, when I was on the other side of the building, I heard wave-like sounds. They seemed to roll across the ceiling and down the gallery walls. I think this sound is created when a critical mass of people are moving relatively quickly on the giant spiral. This causes the entire spiral to move rhythmically, creating friction between thousands of plastic balls. In a sense, the wave sounds are created by actual waves.

The MFAH is to be commended for its bold choice in acquiring this impressive work. But I wonder whether many visitors appreciate its importance. I think they would benefit from a one-page educational handout that discusses the work’s significance in more detail than the five-sentence label.

The only Neto previously exhibited at MFAH was Pé de Três Sonhos (1999), as part of the 2010 exhibition Cosmopolitan Routes: Houston Collects Latin American Art. SunForceOceanLife was purchased through the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund. This thoroughly enjoyable installation is at the MFAH through September 26, 2021. Don’t miss it.

****

Through Sept 26 at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Ruben C. Cordova is an art historian and curator.