Ed Ruscha, traveling on Route 66 between California and his family home in Oklahoma City, would pull off the highway in Amarillo, Texas. “You had to stop and gas up,” he said. A gas station in Amarillo appeared first in his 1963 artist’s book Twentysix Gasoline Stations, and then as the painting Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas, which served as the basis — the standard — for all of Ruscha’s subsequent paintings on the Standard Station theme.

For Robert Smithson, Amarillo was more than a quick stop. He died there, in a plane crash in 1973, while surveying what would become his last artwork, Amarillo Ramp. Completed posthumously, the earthwork follows Smithson’s iconic Spiral Jetty in the form of a partial circle of rock, 140-feet in diameter, rising gradually to a height of about 15 feet, on a dry lakebed on a working ranch in the remote reaches of the hills to the northwest of Amarillo.

One year later, Ant Farm, a group of renegade artist-architects, put ten Cadillacs in the ground on Route 66, now Interstate 40, just east of Amarillo. An iconic roadside attraction, Cadillac Ranch, with its graffiti-covered, half-buried classic cars stoically slanting out of the ground, looms large in the American imagination.

These three well-known works, along with two more locally influential examples — the Amarillo-based Ab Ex copyist Tommy Boberg, and the art collective Dynamite Museum — conceptually underpin and introduce the exhibition Yellow City Art, curated by Jon Revett, at the Contemporary Art Museum Plainview (CAMP). They serve as nodes to relate to the other artists in the exhibition, all of whom are connected to Amarillo in some way and many of whom passed through the artist-run gallery Yellow City Art. And they elevate this exhibition — from what would simply be a celebration of a particular locality and exposé of a regional art scene — to a compelling thesis on the specific art historical influences, cultural confluences, and aesthetics of this west Texas city.

The catalogue for the exhibition (which I helped proofread) expands on this thesis with an extraordinary essay by art historian Amy Von Lintel from West Texas A&M, tracing the intersections of Amarillo and American art history with original research and interviews. There are some truly fascinating nuggets of information in there: like how Louise Nevelson began painting her sculptures gold after visiting Amarillo; or how John Chamberlain had a falling out with the eccentric and wealthy patron Stanley Marsh 3 when he packed one of Chamberlain’s sculptures with stuffed animals; or how one Amarillo artist, Matthew Williams, wore only yellow for two years, then only red, then only blue, in an extended, ongoing performance.

One thing that stands out in this art history of Amarillo is the importance of the patronage of Stanley Marsh 3, an oil tycoon, rancher, media mogul, and heir by marriage to the fortune of the inventor of barbed wire. Marsh brought in Smithson, and Ant Farm, as well as other land artists like Andrew Leicester (who made Floating Mesa in 1980), Nancy Holt (who, I learned, first conceived of what would become the Sun Tunnels while in Amarillo), and others. Marsh also funded the Dynamite Museum’s Sign Project, an eight-year-long public art project and social performance that saw upwards of 5,000 art “road signs” erected throughout the city. And while Yellow City Art was, according to Von Lintel, “an attempt, in part, to break out from under the shadow of Marsh,” his anti-establishment, playful attitude toward art rubbed off on the “democratic not aristocratic” young artist-run gallery, in operation from 1999 to 2001. This combined heritage results in a local art tradition that prizes social engagement and collectivity, eccentric and idiosyncratic visions, and an aesthetic that reflects the vast open spaces of the plains.

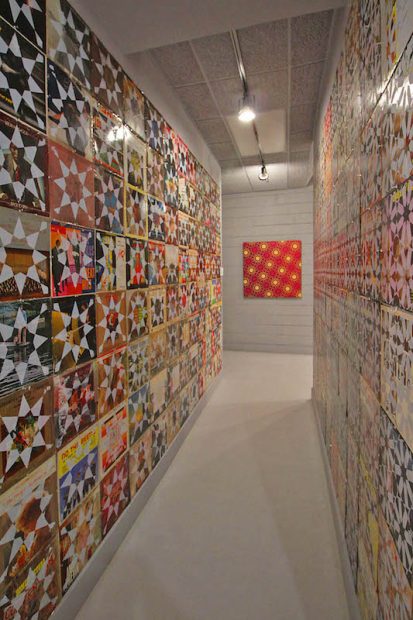

At CAMP, the first room’s documentation and reproductions of Ruscha, Smithson, et al, complemented by the catalogue, establishes this history. Then, passing through a corridor of Revett’s tessellations screenprinted on record covers, the exhibition brings us into the present day, with recent work by current and former Amarillo artists. The resulting exhibition is surprising and wide-ranging, but, owing to the foundation laid in the historical works in the exhibition, it offers a view of Amarillo art that is coherent, syncretic, and satisfying. Being a newcomer, I don’t know enough about the Amarillo art scene to identify any gaping holes in the exhibition’s roster of artists, but the show has clearly been carefully and considerately curated. Many of the artists have little to no web presence, and only someone who is invested in and knowledgeable of the local art community would know about their work, and intimately enough to complement it so well with the other works in the show, and tie it back to the art historical examples that form the basis of the exhibition.

We see echoes of Ed Ruscha in the gradient background of Ashley Epps’ Flower Mountain (2015) and the stark silhouettes of grain silos in Shawn Kennedy’s West Texas Monoliths (2004). Smithson is there in David Villegas’ An Accelerating Loss (2018), an earthen cowboy hat formed of cast soil and concrete. And the playful unorthodoxy of Cadillac Ranch is found in Matthew Williams’ De Stijl Auto Mech drawings (in red, yellow, and blue, of course), and the urban abstractions in René West’s photographs of accumulations of spray paint.

The punk-inflected photographs by Jaime Harmon, plein-air landscapes by Martha Kent Jacobs, dustbowl-like abstractions by Russell Stephenson, and digital collages of cows and astronomical symbols by Victoria Taylor-Gore make for a show of strikingly diverse works that probably wouldn’t make sense together in any other context. But together they create a mood — at turns quirky, cool, and sinister — that evokes something about what Amarillo stands for and contribute to a strong sense of place. This mood is helped along significantly by the video Greetings from Amarillo by Chip Lord (one of the Ant Farmers) with a soundtrack by Amarillo-based musician (and “super weird” city council candidate) Hayden Pedigo.

In a region awash with art shows curtailed by geography, Yellow City Art’s focus on top-notch scholarship and sensitive curation separates it from the run-of-the-mill Texas-art-in-Texas shows. In an email to me, Revett said he pitched the show to the Amarillo Museum of Art, “but they were not that interested.” Their loss. The Contemporary Art Museum Plainview — the scrappy start up now celebrating its one-year-anniversary — is making an impact here, not just in the immediate community of Plainview, but throughout the Panhandle and beyond. Every town deserves something like this, and we’re lucky to have it.

Through Feb., 2019 at Contemporary Art Museum Plainview

*Unless otherwise noted, quotations drawn from Amy Von Lintel, “Gassing Up in Amarillo,” Yellow City Art, exh. cat., Contemporary Art Museum Plainview, 2018.